See Order at bottom of this judgment.

MR JUSTICE MOSTYN:

- The aim of the Localism Act 2011 is to facilitate the devolution of decision-making powers from central government to local communities.

- One devolved power concerns the provision of social housing under Part VI of the Housing Act 1996. This was amended by the 2011 Act to allow a local housing authority to decide what classes of persons are, or are not, qualifying persons for the receipt of social accommodation (see the new section 160ZA(6) and (7)). Section 147 of the 2011 Act inserted a new section 166A into the 1996 Act. This provides, so far as is material to this case:

"(1) Every local housing authority in England must have a scheme (their "allocation scheme") for determining priorities, and as to the procedure to be followed, in allocating housing accommodation.

…

(3) As regards priorities, the scheme shall, subject to subsection (4), be framed so as to secure that reasonable preference is given to:

(a) people who are homeless (within the meaning of Part 7);

(b) people who are owed a duty by any local housing authority under section 190(2), 193(2) or 195(2) (or under section 65(2) or 68(2) of the Housing Act 1985) or who are occupying accommodation secured by any such authority under section 192(3);

(c) people occupying insanitary or overcrowded housing or otherwise living in unsatisfactory housing conditions;

(d) people who need to move on medical or welfare grounds (including any grounds relating to a disability); and

(e) people who need to move to a particular locality in the district of the authority, where failure to meet that need would cause hardship (to themselves or to others).

The scheme may also be framed so as to give additional preference to particular descriptions of people within this subsection (being descriptions of people with urgent housing needs).

…

(5) The scheme may contain provision for determining priorities in allocating housing accommodation to people within subsection (3); and the factors which the scheme may allow to be taken into account include:

…

(c) any local connection (within the meaning of section 199) which exists between a person and the authority's district."

- Therefore, by virtue of the 2011 Act local housing authorities were specifically empowered to include within their allocation schemes a local connection priority within that class afforded a reasonable preference, and, indeed, generally. The guidance given by the government in December 2013 expressly encouraged local authorities to promulgate allocation schemes which gave priority to long-term residents. It stated:

"12. The Government is of the view that, in deciding who qualifies or does not qualify for social housing, local authorities should ensure that they prioritise applicants who can demonstrate a close association with their local area. Social housing is a scarce resource, and the Government believes that it is appropriate, proportionate and in the public interest to restrict access in this way, to ensure that, as far as possible, sufficient affordable housing is available for those amongst the local population who are on low incomes or otherwise disadvantaged and who would find it particularly difficult to find a home on the open market.

13. Some housing authorities have decided to include a residency requirement as part of their qualification criteria, requiring the applicant (or member of the applicant's household) to have lived within the authority's district for a specified period of time in order to qualify for an allocation of social housing. The Secretary of State believes that including a residency requirement is appropriate and strongly encourages all housing authorities to adopt such an approach. The Secretary of State believes that a reasonable period of residency would be at least two years.

….

16. Whatever qualification criteria for social housing authorities adopt, they will need to have regard to their duties under the Equality Act 2010, as well as their duties under other relevant legislation such as s.225 of the Housing Act 2004.

….

18. Housing authorities should consider the need to provide for exceptions from their residency requirement; and must make an exception for certain members of the regular and reserve Armed Forces …

19. It is important that housing authorities retain the flexibility to take proper account of special circumstances. This can include providing protection to people who need to move away from another area, to escape violence or harm; as well as enabling those who need to return, such as homeless families and care leavers whom the authority have housed outside their district, and those who need support to rehabilitate and integrate back into the community.

…

26. Housing authorities have the ability to take account of any local connection between the applicant and their district when determining relative priorities between households who are on the waiting list (s.166A(5)). For these purposes, local connection is defined by reference to s.199 of the 1996 Act.

27. Housing authorities should consider whether, in the light of local circumstances, there is a need to take advantage of this flexibility, in addition to applying a residency requirement as part of their qualification criteria. …"

- Therefore, pursuant to the power granted by Parliament, and spurred on by the strong encouragement of the government, many local authorities have promulgated allocation schemes which incorporate a prioritisation of people with a local connection. These in turn have given rise to a number of lawsuits where other classes of people have complained that this prioritisation has unlawfully discriminated against them. Coincidentally the most recent such case was about the very allocation scheme with which I am concerned: R (on the application of TW & Ors) v London Borough of Hillingdon & Anor [2018] EWHC 1791 (Admin).

- This case has a long history. During its course the allocation scheme promulgated by the defendant ("Hillingdon") has gone into a second edition. The current one dates from December 2016. It incorporates a prioritisation for those people who have been resident in the borough for 10 years, although that, of course, is not the only criterion. The impact of that particular criterion is hedged about with numerous variants, exceptions and deeming provisions, which I will endeavour to describe later.

- The claimant, a Kurd of Turkish nationality, was awarded refugee status by the Home Secretary in April 2013. Up to that point he was an asylum seeker accommodated at the direction of the government in Hillingdon. He was notified that he had to leave that accommodation by December 2013. He then approached Hillingdon seeking housing and was given temporary accommodation pursuant to the provisions of Part VII of the 1996 Act. Cutting a long story short, he remains accommodated under Part VII. On 1 July 2016 the claimant issued the proceedings before me. He claims that the decision not to register him on Hillingdon's allocation scheme was unlawful. Primarily, he claims that the scheme, inasmuch as it incorporates a 10-year residence criterion, unlawfully discriminates him as a refugee and a foreign national.

- In Ghaidan v. Godin-Mendoza [2004] UKHL 30, [2004] 2 AC 557, Lord Nicholls of Birkenhead famously stated at para 9:

"Discrimination is an insidious practice. Discriminatory law undermines the rule of law because it is the antithesis of fairness. It brings the law into disrepute. It breeds resentment. It fosters an inequality of outlook which is demeaning alike to those unfairly benefited and those unfairly prejudiced. Of course all law, civil and criminal, has to draw distinctions. One type of conduct, or one factual situation, attracts one legal consequence, another type of conduct or situation attracts a different legal consequence. To be acceptable these distinctions should have a rational and fair basis. Like cases should be treated alike, unlike cases should not be treated alike. The circumstances which justify two cases being regarded as unlike, and therefore requiring or susceptible of different treatment, are infinite. In many circumstances opinions can differ on whether a suggested ground of distinction justifies a difference in legal treatment. But there are certain grounds of factual difference which by common accord are not acceptable, without more, as a basis for different legal treatment. Differences of race or sex or religion are obvious examples. Sexual orientation is another. This has been clearly recognised by the European Court of Human Rights: see, for instance, Fretté v France (2003) 2 FLR 9, 23, para 32. Unless some good reason can be shown, differences such as these do not justify differences in treatment. Unless good reason exists, differences in legal treatment based on grounds such as these are properly stigmatised as discriminatory."

- Therefore, in order to establish discrimination there must be proof of (a) at least two alike cases and (b) the fact of different treatment of those cases. Alternatively, there must be proof of (a) at least two unalike cases and (b) the fact of the same treatment of those cases. This would suggest that you need to have a subject case and a comparator case. However, the cases seem to suggest that an easier approach is simply to assume the existence of different treatment and to move directly to the question of justification. In AL (Serbia) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2008] UKHL 42, [2008] 1 WLR 1434 at paras 24 – 25 Baroness Hale stated:

24. It will be noted, however, that the classic Strasbourg statements of the law do not place any emphasis on the identification of an exact comparator. They ask whether "differences in otherwise similar situations justify a different treatment". Lord Nicholls put it this way in R (Carson) v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions [2006] 1 AC 173, at para 3:

". . . the essential, question for the court is whether the alleged discrimination, that is, the difference in treatment of which complaint is made, can withstand scrutiny. Sometimes the answer to that question will be plain. There may be such an obvious, relevant difference between the claimant and those with whom he seeks to compare himself that their situations cannot be regarded as analogous. Sometimes, where the position is not so clear, a different approach is called for. Then the court's scrutiny may best be directed at considering whether the differentiation has a legitimate aim and whether the means chosen to achieve the aim is appropriate and not disproportionate in its adverse impact."

25. Nevertheless, as the very helpful analysis of the Strasbourg case law on article 14, carried out on behalf of Mr AL, shows, in only a handful of cases has the Court found that the persons with whom the complainant wishes to compare himself are not in a relevantly similar or analogous position (around 4.5%). This bears out the observation of Professor David Feldman, in Civil Liberties and Human Rights in England and Wales, 2nd ed (2002), p 144, quoted by Lord Walker in the Carson case, at para 65:

"The way the court approaches it is not to look for identity of position between different cases, but to ask whether the applicant and the people who are treated differently are in 'analogous' situations. This will to some extent depend on whether there is an objective and reasonable justification for the difference in treatment, which overlaps with the questions about the acceptability of the ground and the justifiability of the difference in treatment. This is why, as van Dijk and van Hoof observe,… 'in most instances of the Strasbourg case law . . . the comparability test is glossed over, and the emphasis is (almost) completely on the justification test'."

A recent exception, Burden v United Kingdom, app no 13378/05, 29 April 2008, is instructive. Two sisters, who had lived together for many years, complained that when one of them died, the survivor would be required to pay inheritance tax on their home, whereas a surviving spouse or civil partner would not. A Chamber of the Strasbourg Court found, by four votes to three, that the difference in treatment was justified. A Grand Chamber found, by fifteen votes to two, that the siblings were not in an analogous situation to spouses or civil partners, first because consanguinity and affinity are different kinds of relationship, and secondly because of the legal consequences which the latter brings. But Judges Bratza and Björgvinsson, who concurred in the result, would have preferred the approach of the Chamber; and the two dissenting judges thought that the two sorts of couple were in an analogous situation. This suggests that, unless there are very obvious relevant differences between the two situations, it is better to concentrate on the reasons for the difference in treatment and whether they amount to an objective and reasonable justification.

- This approach is mirrored in other fields of law. Why examine whether there has been a breach of a duty of care if there has in fact been no compensable damage caused? Why examine whether there is a grave risk that a child would be caused physical or psychological harm under Article 13(b) of the 1980 Hague Child Abduction Convention if there are in place sufficient safeguards in the other state (see Re E (Children) [2011] UKSC 27, [2012] AC 144 at para 36)?

- There is however a problem with this approach in this sort of case because the scale of the differential treatment is directly linked to the justificatory response. In order to judge if the different treatment, actual or potential, is objectively justified you need to know what the scale of the differential is.

- Therefore, there must be, if not an exact comparator, at least an analogue.

- In his skeleton argument Mr Burton put it this way:

"It is obvious that refugees are inherently less likely to be able to meet the 10 Year Residency Rule than non-refugees. Furthermore, like the claimant, refugees are often forced to apply for assistance as a homeless person at the point they are accepted as being a refugee. Therefore, refugees are by virtue of their status as a refugee intrinsically more likely to be in the lowest priority band (Band D) than other homeless applicants to the scheme. Furthermore, unlike other homeless applicants who do not meet the 10 Year Residency Rule, homeless refugees are unlikely to have been able to choose where they lived in the UK prior to becoming homeless. This is in the context of them having had to leave their country of nationality and come to the UK because of persecution."

- For the Intervener, Mr Squires QC put it thus:

"Residency requirements, especially for as long as 10 years, are intrinsically liable to disadvantage non-UK nationals. The reason is obvious. UK nationals are significantly more likely to have lived in the UK, and in any particular area of it, for the past 10 years, than non-UK nationals. Or to put it another way, non-UK nationals are significantly more likely to be more recent arrivals in the country, and thus in any particular area of the country, than UK nationals."

- Somewhat to my surprise, Mr Rutledge QC in his skeleton argument conceded that there was the potential for differential treatment of the claimant in his status as a refugee recently arrived in Hillingdon. He did so as a result of dicta from the Master of the Rolls in R (On the Application of H & Ors) v Ealing London Borough Council [2017] EWCA Civ 112, [2018] PTSR 541, [2018] HLR 2 at para 59, where he said:

"In short, it is contradictory of Ealing to concede, on the one hand, that for the purposes of EA s19(2) the WHPS [working household priority scheme] is a PCP [provision, criterion or practice], and, on the other hand, to seek to rely on Ealing's Housing Policy as a whole to rebut the PCP's discriminatory impact on the relevant Protected Groups. What this highlights is that the matters on which Ealing relies, the so-called safety valves, are matters which properly are relevant to justification under EA 2010 s.19(2)(d) rather than the existence of indirect discrimination under EA 2010 s.19(2)(a)-(c)."

I have to say that I find this passage quite confusing. Obviously, the local authority in that case was going to concede that the priority scheme under attack was accurately to be described as a provision criterion or practice. Further, it would seem that the local authority took the stance that if the scheme did have a discriminatory impact on a protected group then that impact was negated by the council's overall housing policy taken as a whole. I do not read the passage as conveying a concession that the particular element of the scheme did have a discriminatory impact, or conveying a finding by the court to the same effect.

- The claimant is a recent arrival in Hillingdon who is a refugee. He is discriminated against in favour of long-term residents not because he is a refugee but because he is a short-term resident. Nobody is suggesting that discrimination on that basis is to be impugned. Indeed, as I have pointed out, it has been expressly authorised by Parliament and strongly encouraged by the government.

- The correct analogue is therefore another short-term resident who is not a refugee. That analogue might be a recent arrival from another part of the UK or a recent arrival from the EEA exercising treaty rights. The same treatment is meted out to the claimant and the analogue – both are denied priority by virtue of the 10-year residency rule. The claimant's case can only get off the ground if he can show that his circumstances and those of the analogue are materially different: that they are unalike cases. If he can show that they are unalike then the defendant has to justify the same treatment being applied to both.

- But are they unalike? Mr Burton says the circumstances of a refugee and those of a voluntary migrant from Yorkshire or France are different because the refugee has no choice but to apply in Hillingdon whereas the analogue comes to Hillingdon by choice. Further, the refugee may be more vulnerable as a result of the persecution he has suffered which has resulted in the award of refugee status. All of this is true, but so what? The reason that each has started the 10-year journey may be different but that is immaterial to the process of starting the clock and counting the days, which is all that the measure stipulates.

- In R (On the Application of H & Ors) v Ealing London Borough Council Mr Justice Supperstone held that the circumstances of Irish travellers were so different to other short-term residents who were counting days under the rule as to make the uniform application of the rule to them unjustified. That decision I can well understand. Travellers are a nomadic people. It is in their blood and is their fundamental tradition. Therefore, as a matter of probability it is surely much more likely that an Irish traveller will not complete the 10-year journey than his or her analogue. The traveller and the analogue are unalike cases which should be treated differently.

- But the same cannot be said when comparing a recently arrived refugee to his or her analogue. In my opinion, for the purposes of assessing the impact of the 10-year rule, when it comes to starting the clock and counting the days their situations are the same. I therefore do not find that there is any actual discrimination here.

- I will nonetheless address the justification argument. It may be a higher court disagrees with my primary conclusion, and, as stated above, Mr Rutledge QC has conceded that the measure has the capability to inflict indirect discrimination.

- In RF v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions [2017] EWHC 3375 (Admin) at paras 42 - 43 I attempted to précis the law concerning the justification of discrimination. I stated:

"42. In determining whether actual discrimination is objectively justified the court applies a four-limbed test. It must be satisfied, the onus being on the discriminator, that:

i) the objective of the measure is sufficiently important to justify the limitation of a protected right; and

ii) the measure is rationally connected to that objective; and

iii) a less intrusive measure could not have been used without unacceptably compromising the achievement of the objective; and

iv) when balancing the severity of the measure's effects on the rights of the persons to whom it applies against the importance of the objective, to the extent that the measure will contribute to its achievement, the former outweighs the latter.

See Huang v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2007] 2 AC 167 and Bank Mellat v HM Treasury (No 2) [2014] AC 700. …

43. Although the onus is on the defendant there is an overarching standard of review of which I must be satisfied at all stages of the exercise. That is the "manifestly without reasonable foundation" test or standard. There can be no doubt that this applies to this social security measure: see R (Carmichael) v Secretary of State for Work and Pensions [2016] 1 WLR 4550. This reflects the wide margin of appreciation given to national governments when enacting measures with a macro-economic effect. Plainly, it will only be in a very strong and obvious case that the court will strike down a legislative measure which is an expression of the democratic process. I think that is the effect of the word "manifestly"."

- As stated above, this case concerns the provision of social housing by a local housing authority. In my opinion there is equally in this field a generous margin of appreciation. The court should be very cautious indeed when faced with a claim to strike down a measure which seeks to parcel out fairly a local authority's housing stock at a time where there is a national housing crisis and where the demand for public housing vastly exceeds the supply. Were the court to afford an advantage to a class of claimants (here, refugees) then it will be at the expense of another group who will find themselves jumped in the queue. When it comes to housing local authorities have to make hard political judgments of a macro-economic nature which the courts are ill-equipped to second-guess. These judgments are the expression of the local democratic process. Hence the need for there to be a strong and obvious case before the court will interfere.

- The justification principles apply equally whether the discrimination complained of falls under section 19 of the Equality Act 2010 or Article 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights (if that latter provision is in fact in play).

- I am wholly satisfied that if there is actual discrimination here, then it is amply objectively justified. I do not need to decide, therefore, the interesting question whether the measure here is within the ambit of Article 14, which is not a free-standing provision but only operates when another right is in action.

- The first point to be made within the justification exercise is that if the claimant and his analogue are unalike cases they are only very marginally unalike, and that therefore the ability to depart from the rule need only be modest.

- The rule exists as part of a detailed and sophisticated scheme the over-arching, key theme of which is the meeting of housing needs. The scheme is very clearly described in paras 9 – 15 of Mr Justice Supperstone's judgment, and I freely admit that I have drawn on his description in what follows.

- Para 1.2 sets out the key objectives of the Allocation Scheme. They are to:

" - Provide a fair and transparent system by which people are prioritised for social housing.

- Help those most in housing need.

- Reward residents with a long attachment to the borough.

- Encourage residents to access employment and training.

- Make best use of Hillingdon's social housing stock.

- Promote the development of sustainable mixed communities."

- Para 1.2 further states:

"The Council will register eligible applicants who qualify for the reasonable preference criteria and certain groups who meet local priority. In addition, the Council will ensure that greater priority through 'additional preference' is given to applicants who have a longer attachment to the borough, are working, … and childless couples."

- Section 4 refers to the Council operating a 'Choice Based Lettings Scheme' through a central lettings agency known as "Locata", and section 5 sets out how the Choice Based Lettings Scheme operates. It states:

"5.1 Priority Banding

Housing need is determined by assessing the current housing circumstances of applicants. A priority 'band' is then allocated according to the urgency of the housing need. There are three priority bands as follows

Band A – This is the highest priority band and is only awarded to households with an emergency and very severe housing need.

Band B – This is the second highest band and is awarded to households with an urgent need to move.

Band C – This is the third band, and the lowest band awarded to households with an identified housing need.

If following an assessment it is determined that an applicant has no housing need, they cannot join the housing register…"

- Section 6 provides that in certain specified cases, an allocation may be made outside of the Choice Based Lettings Scheme. These include "where homeless households have been in temporary accommodation for longer than the average period, they will be made one direct offer of suitable accommodation".

- Section 12 deals with Reasonable Preference Groups and states, so far as is relevant:

"The council will maintain the protection provided by the statutory reasonable preference criteria in order to ensure that priority for social housing goes to those in the greatest need…

12.1 Homeless household

This applies to people who are homeless within the meaning of Part 7 of the 1996 Housing Act (amended by the Homelessness Act 2002 and the Localism Act 2011).

…

Where the Council has been able to prevent homelessness and the main homelessness duty has been accepted, applicants will be placed in one of the following bands:

Band A – in temporary accommodation but the landlord wants the property back AND the council cannot find alternative suitable temporary accommodation. Where an applicant fails to successfully bid within 6 months, a direct offer of suitable accommodation will be made. If the property is refused the Council will discharge its duty under Part VII of the Housing Act and withdraw any temporary accommodation provided.

Band B – In Bed and Breakfast, council hostel accommodation or women's refuge.

Band C – In other forms of temporary accommodation.

Where the Council has been unable to prevent homelessness and the main homelessness duty has been accepted, applicants with less than 10 years continuous residence in the borough will be placed in Band D.

…

12.4 Medical grounds

If you apply for housing because your current accommodation affects a medical condition or disability, your application will be referred to the council's medical adviser or occupational therapy team depending on what you have put in your application for assessment.

…

12.6 Hardship grounds

There are a number of households applying to the housing register who experience serious hardship because of a combination of different factors which make the need for re-housing more urgent than when considered separately.

The decision as to the appropriate priority 'band' will depend on both the combination and degree of the various factors with a view to ensuring that the greatest priority is given to those in the greatest need.

In circumstances where this applies, a panel of officers (Hardship Panel) will undertake a review of the case to determine whether priority for re-housing is necessary.

The following priority banding will be considered

Band B – the applicant or a member of their household has multiple needs or has an urgent need to move. Examples include:

- To give or receive care or support from/to a resident in the borough, avoiding use of residential care. It is constant care to/from a close relative as evidenced by a professional's report and supported by the Council's Medical Adviser; …

- Other urgent welfare reasons."

- Section 14 provides that additional priority is awarded in order to determine priorities between people in the reasonable and local preference groups. It is awarded in circumstances which include:

"14.3 10-year continuous residency

Additional priority is awarded to those who have a local connection by living in the borough continuously for a minimum period of ten years. This will support stable communities and reward households who have a long-term attachment to the borough.

Local connection will normally mean that an applicant has lived in Hillingdon, through their own choice, for a minimum of 10 years up to and including the date of their application, or the date on which a decision is made on their application, whichever is later.

14.4 Working households

Additional priority will be given to households who are in housing need and are working but are on a low income which makes it difficult to access low cost or outright home ownership. This will encourage people who can, to work and raise levels of aspiration and ambition.

This policy applies to households where:

- At least one adult household member is in employment.

- The employment should be a permanent contract, self-employment or part time for a minimum of 24 hours per week.

- The worker should have been in employment for 9 out of the last 12 months.

- Band A – where the household's housing need is 'Band B' + working.

- Band B – where the household's housing need is 'Band C' + working"

- Finally, I highlight para 10.9 which is headed "appealing against a decision" and which grants applicants a right of review against any decision made under the terms of the policy with which they do not agree.

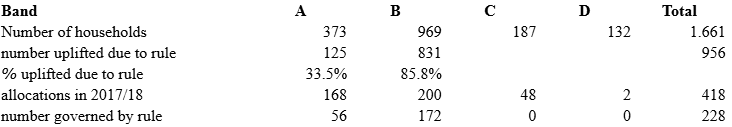

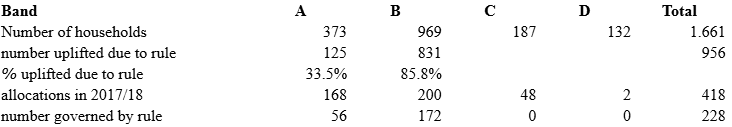

- It can be seen that the 10-year residence rule is not by any means the only gateway onto the register, nor is it, once you have got there, the only gateway to an uplift. There are other ways in, or up. I consider it misleading to describe these as "safety valves". A safety valve is a valve that opens automatically to relieve excessive pressure. That is quite the wrong way of looking at these alternative ways in or up. The data shows that the 10-year residence rule is by no means the only governing criterion. It shows:

Thus, in 2017/18 228 or 54.5% of the allocations were governed by the rule. 190 were not.

- In my introductory paragraphs I have sought to set out in simple terms the claimant's primary contention. The full scope of his challenge is in fact threefold. He challenges (1) the 10-year rule in paragraph 2.2.4 (the residence qualification); (2) the additional preference (the residence uplift) for households in bands C and B under paragraph 14.3; and (3) the additional preference (the working household uplift) for those in bands C and B who are working households on low income under paragraph 14.4.

- So far as Ground (3) is concerned I agree entirely with the reasoning of Mr Justice Supperstone. Only a handful of cases are caught by it; the ground is limited and focused. Its objective is important and rational, and it is hard to conceive what lesser measure would have the same effect. It is manifestly not without a reasonable foundation. In fairness Mr Burton did not press this ground in his submissions with any particular vigour. In my judgment this ground is virtually unarguable.

- I turn to Grounds (1) and (2) which are the 10-year residence qualification and uplift. The question is whether it is proportionate and justifiable to apply this criterion equally to two recent arrivals, one of whom is a Kurdish refugee from Turkey, and the other is, say, Dick Whittington who has set off from poverty stricken circumstances in Lancashire to seek his fortune in London. In answering this question, I must apply the four-limbed test set out above. I must also be satisfied that the equal treatment of these unalike cases (as I must assume) is not manifestly without a reasonable foundation.

- I turn to the four-limbed test:

i) Is the objective of the rule, whether the qualification itself, or the uplift, sufficiently important to justify the limitation of a protected right? For these purposes a limitation of a protected right is assumed. In my judgment the answer to this question is plainly yes. The rule is obviously highly important and is an expression of national and local democratic processes. The actual limitation is, as I have explained, minimal and requires no more than that the claimant is treated the same as any other recent arrival.

ii) Is the measure is rationally connected to that objective? The answer to this is plainly yes.

iii) Could a less intrusive measure not have been used without unacceptably compromising the achievement of the objective? In my judgment to water down the rule for refugees to say 5 years would be quite wrong and arguably unlawful positive discrimination in their favour. The alternative ways in or up, set out above, entirely negate any merit which this argument might otherwise have.

iv) When balancing the severity of the measure's effects on the rights of the persons to whom it applies against the importance of the objective, to the extent that the measure will contribute to its achievement, does the former outweigh the latter? The answer to this is plainly no. The latter greatly outweighs the former.

- I am satisfied that the scheme is not manifestly without a reasonable foundation.

- I now turn to a further complaint made by the claimant which is that Hillingdon failed to comply with its Public Sector Equality Duty.

- The duty is expressed in section 149(1) of the Equality Act 2010, which provides:

"A public authority must, in the exercise of its functions, have due regard to the need to:

(a) eliminate discrimination, harassment, victimisation and any other conduct that is prohibited by or under this Act;

(b) advance equality of opportunity between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it;

(c) foster good relations between persons who share a relevant protected characteristic and persons who do not share it."

- The obligation on every public authority is to "have due regard to the need to" eliminate or advance or foster the goals that then follow. The noun "need" supplies an imperative quality. The noun "regard" means no more than to have in mind. The adjective "due" means "such as is necessary or requisite; of the proper quality or extent; adequate, sufficient", as in "driving without due care and attention". Therefore, the public authority must have sufficiently in mind, when exercising its functions, the necessity of achieving these goals.

- Any challenge can only be to process and not to outcome (see Hotak v London Borough of Southwark [2015] UKSC 30, [2015] 2 WLR 1341 at [74] – [75]). The 2010 Act does not provide for a statutory right of appeal against any alleged breach, but left any challenge to judicial review proceedings. Therefore, the classic judicial review standards of irrationality or perversity must be satisfied if a challenge is to succeed (see R (on the application of Ghulam & Ors) v Secretary of State for the Home Department & Anor [2016] EWHC 2639 (Admin) at [329]).

- In this case an Equality Impact Assessment (EIA) was undertaken by the defendant for each iteration of the scheme. They are very full. Such an assessment is not mandated by the 2010 Act but as Mr Justice Wyn Williams stated in R (Diocese of Menevia) v City and County of Swansea Council [2015] EWHC 1436 at [98]:

"The fact that a public body has produced an EIA in appropriate form in advance of the decision in question is, usually, convincing evidence that it has had regard to its public sector equality duties when making the relevant decision."

- The claimant says that these EIAs fail to take account of the impact of the schemes on foreigners. A refugee is not a protected class as such under the Act, but gains protection by virtue of his or her nationality. The first EIA expressly and conscientiously considered the impact of the scheme on people arriving from outside this country. The second EIA did so implicitly.

- There was no failure to give due regard to any of the section 149 matters, let alone an irrational or perverse omission.

- Finally, the claimant says that the 10-year rule is irrational in terms of its length. It is, apparently, a national record, and twice as long, at least, as any other such condition anywhere else. I cannot accept this argument. The guidance given by the government set a minimum level but no maximum. It cannot be said that to adopt a 10-year rule is outwith the power granted by Parliament or at variance with the guidance given by government.

- For all these reasons the claim for judicial review is dismissed.

______________

Order

by the Honourable Mr Justice MOSTYN

UPON hearing Counsel Mr Jamie Burton for the Claimant, and Mr Kelvin Rutledge QC and Mr Andrew Lane for the Defendant, and Mr Dan Squires QC (by written submissions only) for the Intervener at a hearing at the Royal Courts of Justice, Strand, London, WC2A 2LL on 17 and 18 July 2018

IT IS ORDERED

- The claim for judicial review is dismissed.

- The Claimant is to pay the Defendant's reasonable costs of this claim (to be set-off against the costs order made against the Defendant on 23 May 2017), the said costs to be subject to a detailed assessment if not agreed and subject to a determination of the Claimant's ability to pay such costs pursuant to section 26 of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act 2012

- There be no order for costs in respect of the Intervener.

- There be a detailed assessment of the Claimant's legal aid costs.

- The Claimant's application for permission to appeal is refused.