Mrs Justice Cockerill:

Introduction

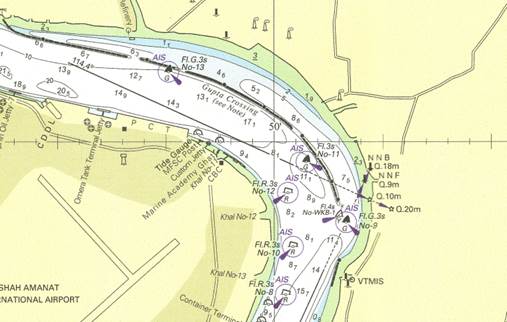

- At about 08:17:35 local time on Friday 14 June 2019 a collision occurred between the Claimants' container vessel "X-PRESS MAHANADA" ("XPM") and the Defendants' product tanker ("BURGAN"). It was very nearly a head on collision. It occurred at the Gupta Crossing which is a significant bend in the Karnaphuli River ("the River") in the approaches to the Bangladeshi port of Chattogram. Both vessels were under pilotage - XPM incoming, and BURGAN outgoing.

- The collision took place very close to the northern edge of the navigable channel at the Gupta bend. This is a narrow channel to which Rule 9(a) of the Collision Regulations applies: namely that each vessel should keep as near to the outer limit of the channel or fairway on her starboard side as is safe and practicable.

- It is not in issue that at the time of the collision BURGAN was in her wrong water - this location was, for her, close to the outer limit of the channel on her port side. BURGAN's defence to this claim is all about how she got there. She contends that she was where she was due to the fault of a third vessel, the "SHAKTI SANCHAR" ("SS"), an amphibious warfare ship operated by the Bangladeshi army. That vessel, which is not a party to this action, entered into the channel navigating broadly east to west between the two vessels fairly shortly before the collision occurred.

- XPM is a container vessel 182.52m loa and 25.20m in beam. She was built in 2007. She was owned by Mackenzie Shipping Pte Ltd. of Singapore and flew the Singapore flag. She is of 18,017 GRT and 23896DWT and is powered by a MAN B&W 9L 58/64 diesel engine developing 12,600 kW at 428RPM. Her main engine drives a right hand turning, 4 bladed, controllable pitch propellor. That controllable pitch propeller gives greater control over her speed than a fixed pitch propeller so she is not bound to specific speeds e.g half ahead, slow ahead.

- At the material time, XPM was partially laden with about 20,000 tons of containerized general cargo. Her drafts were 9.3m forward and 9.5m aft. She had the following manoeuvring speeds:

|

Engine Order |

Pitch |

Loaded Speed |

Ballast Speed |

|

Full Ahead |

60 |

13.0 |

13.2 |

|

Half Ahead |

45 |

9.8 |

10.5 |

|

Slow Ahead |

35 |

7.7 |

8.0 |

|

Dead Slow Ahead |

25 |

5.5 |

6.0 |

- BURGAN is a product tanker, of 185.99m loa and 32.20m in beam. She was built in 2014. She is owned by Kuwait Oil Tanker Company S.A.K. and flies the Kuwaiti flag. She is of 46,330DWT, 31,445 GRT, 12,436 NRT and is powered by a 7RT-FLEX 50-D slow speed diesel engine manufactured by Hyundai-Wartsila, developing 11,936 BHP. She had completed discharge operations on the previous evening and was proceeding outbound in ballast. Her drafts were 6.3m forward and 8.0m aft.

- She had the following manoeuvring speeds:

|

Engine Order |

RPM |

Loaded Speed |

Ballast Speed |

|

Full Sea |

96 |

15.29 |

16.10 |

|

Full Ahead |

69 |

11.17 |

12.06 |

|

Half Ahead |

49 |

7.96 |

8.59 |

|

Slow Ahead |

34 |

5.55 |

5.99 |

|

Dead Slow Ahead |

29 |

4.75 |

5.12 |

- SS was not represented at the trial and there is limited information available about her. What there is discloses that she is a Landing Craft Tank ("LCT"), built in 2012, of 65.70m loa, 12 m in beam and has the capacity to carry 1 helicopter, 9 tanks and 150 troops.

- Until very late in the day the factual evidence base was essentially entirely agreed; and the evidence both as to the navigation of the vessels at the time and as to what was said at the time remained uncontentious. The account which follows reflects that uncontentious evidence, except where differences are highlighted explicitly.

- The main sources of this evidence are:

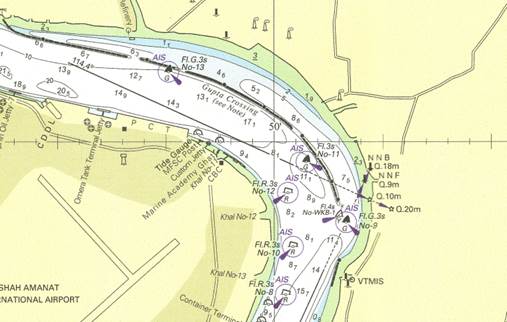

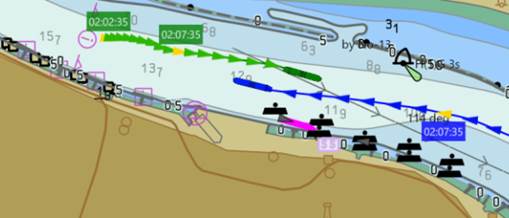

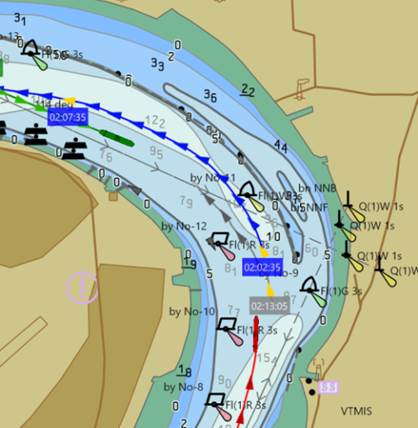

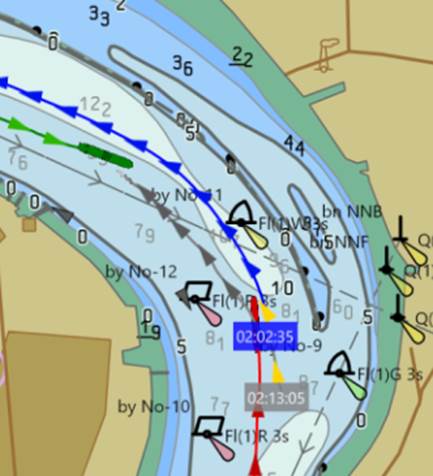

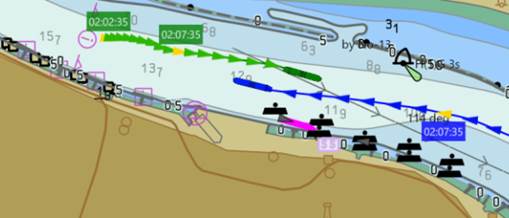

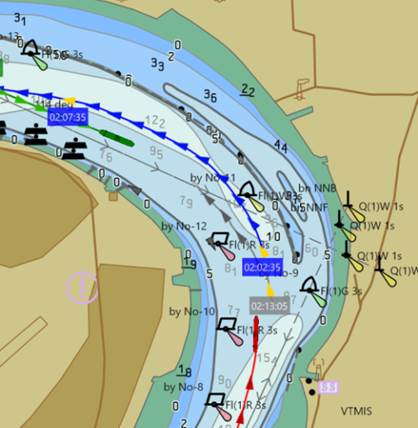

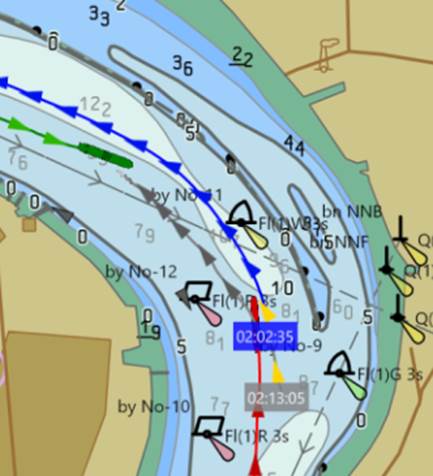

1) The Avenca MADAS Replay. This is a video plot of the navigation of all vessels in the River from 0747:35 until 0822:35 on 14 June 2019 prepared by Avenca on behalf of both parties using the data available to them from the AIS and the information held by the vessels' Voyage Data Recorders ("VDRs"). This was supplemented by a number of stills, extracts from which are referred to below and details of which are embedded in this judgment;

2) The Agreed Combined VDR Transcript from both vessels. All conversations on the bridge of each vessel are recorded by the VDR. The Agreed Transcript sets out everything that was said, and heard, on the bridge of both vessels;

3) An ECDIS video replay and some images from the radar screens. This material was of less utility as it was agreed that neither vessel was consulting its radar at the time;

4) There was also the Admiralty chart and a number of "what if" reconstructions positing certain alternative courses of action.

- Another type of document to which much reference was made were the passage plan. I asked the Assessors to assist as to the purpose and significance of passage plans and they responded thus:

"A formal Passage Plan (berth to berth) is a requirement of SOLAS Chapter V Regulation 34, in addition to the direction provided to the vessel by Sea Consortium PTE. Ltd (Marine Department Document - Revision No 0 (01st Jan, 2018)) and for BURGAN, the Kuwait Oil Tanker Company S.A.K. - Passage Route Plan Document Rev 02 Dated 23 Jan 2019. Both flag states of XPM, BURGAN and the State of Bangladesh are signatories to the SOLAS Convention.

A Passage Plan has four stages: Appraisal, Planning, Execution and Monitoring. It is vital for safety in respect of identifying hazards and preventing accidents, but also contributes towards efficiency, regulatory compliance, environmental protection and enhanced maritime security.

Local knowledge of the Pilot coupled with movements of vessels and other circumstances on the day may result in a deviation from the Ship's Plan in terms of precise timing and execution. The Master/Pilot Exchange provides a means of establishing not only the specific characteristics of the vessel, but also any differences between the ship's plan and the pilot's intentions."

- I had the benefit of passage plans for both BURGAN and XPM. They were rather different documents, with BURGAN's being more detailed than XPM's. BURGAN's indicated a 10 knot speed, and XPM's an 8 knot speed. I sought assistance from the nautical assessors as to whether these represented speeds over the ground ("SOG") or speeds through the water, following some debate between the parties and a suggestion for XPM that they were speeds through the water. Their response was:

"It would be logical that these speeds should be speed over the ground as they form part of the EXECUTION phase of a Passage Plan and are often intended to relate to maintaining a safe schedule for the passage, ensuring that the ship achieves the required times for passing or arriving at key points. This is a ship produced plan however, and the Pilot's plan for the passage may differ."

- Ultimately the answer is that there is no clear answer as to whether both were on the basis of SOG or one was, and not the other. XPM suggested that her passage plan was through the water (because otherwise her speed, after allowance was made for tide, would be dead slow), while BURGAN's was SOG. I conclude that given that the plan is a ship produced document and yields to the pilot's plan the plans are of limited utility. It is therefore not appropriate to conclude that XPM's exceeding of her passage plan speed (if that plan were indeed based on SOG, which is by no means clear) was inappropriate.

- XPM was engaged on the Upper Bay of Bengal line service between Columbo in Sri Lanka and Chittagong. She was under the command of Captain Pranjul Prasad. XPM arrived off Chittagong on 7 June 2019 and dropped anchor pending berth availability. On 13 June 2019 she received a call from Chittagong Port Control, advising that the Pilot would board at 0800 the following morning.

- The weather at around 0536 when Captain Prasad took over control of the XPM's navigation on 14 June 2019 was cloudy with good visibility. The wind was from the South East, Bf 3, and high tide was predicted at Chittagong for 1123, with a height of tide of 4.4m above chart datum. Her bridge was manned by the Chief Officer, Third Officer, the duty AB and the Master. The AB was at the helm and was hand steering.

- The bridge equipment at this time, and at the time of the collision, was set up as follows. The X-band ARPA radar was operating in North-up display, in relative motion and on the 1.5 NM range scale, although the range scale was increased at regular intervals. The radar sweep was centred and the ARPA was set up to display true target vectors of length 20 minutes and true trails of length of 30 seconds. The S-band ARPA radar was operating in North-up display, in relative motion and on the 0.75 NM range scale. The radar sweep was off-centred and the ARPA was set up to display true target vectors of length 12 minutes. The two ARPA radars had the charted course overlaid onto the radar display. Both ECDIS were in operation and were showing XPM's position in real time, overlaid onto the appropriate electronic chart. Both ECDIS had the AIS targets overlaid onto the electronic chart. In addition to the ECDIS, the deck officers were monitoring the vessel's position using a British Admiralty paper chart.

- BURGAN arrived at Chittagong on 10 June 2019 and undertook lightening of cargo to barges at Alpha Anchorage prior to moving to a river berth at DOJ‐6 on 12 June 2019. Cargo discharge operations were completed at DOJ‐6 during the evening of 13 June 2019. Movement of vessels over 175m loa is not permitted on the Karnaphuli River during the hours of darkness and so it was necessary to await the daylight high tide on 14 June 2019 in order to depart from the port. It was initially advised that the pilot would board around 0630 on 14 June 2019. The pilot, Pilot Ataul, arrived at 0724. The Master/Pilot exchange took place between 0724 and 0730.

- BURGAN's Master was not entirely satisfied with the pilot's level of engagement. He reported that the pilot did not engage with the information exchange process at first and it was necessary to direct him to the chart table so that the discussion could take place. BURGAN's Master says that throughout this discussion the pilot appeared overly confident and disinterested in the exchange and that, although disappointing, this was quite typical of the approach adopted by the pilots that he had previously met in Chittagong.

- Unmooring of the vessel commenced at 0736. By 0754 all lines were clear and the anchor was clear shortly afterwards at 0758. Once the vessel was all clear from the berth, the BURGAN's master and her pilot moved to the centre console of the bridge where the radar and ECDIS displays are. The Pilot remained close to the VHF radio and occasionally moved from behind the console to the front of the bridge. BURGAN's master remained in the vicinity of the centre console and the main engine telegraph.

- XPM's Pilot came on to her bridge at 0750. She entered the Karnaphuli River at 0757 (C-20½). Her SOG was about 11.5 knots. Her data shows that her SOG remained above 10 knots (and generally above 11 - 11.5 knots) for the period from C-19 until the collision itself (7-8 knots through the water). BURGAN's principal contention against XPM is that this speed was excessive. This point is considered further below.

- The entry to Chattogram (still widely known as Chittagong) is along a stretch of the river which is slanted initially NNE, before taking a sharp turn to the west. There is then a WNW stretch into the port. The sharp turn in the river is known as the Gupta Crossing. At that point the navigable part of the river narrows.

- The Admiralty chart for the area has the following Note: "The Karnaphuli River is narrow with sharp bends at Gupta Crossing area. Mariners are advised to navigate with extreme caution when transiting the river."

- The north eastern part is constrained by a training wall which remains beneath water level at all times except ones of extreme drought. The south western part has somewhat shifting depths, and just around the bend towards the port are a range of mooring buoys.

- To mark the navigable limits there are a series of physical buoys. In particular at the NE of the bend, in front of the wall is Buoy 11. The Admiralty chart 102 also has a heading of 114.40 marked. The purpose of this is unclear. It involves a heading well to the port of the line indicated by the Col Regs; if followed it actually positions a vessel to the port of the channel as the restraining wall comes to an end and the bend is negotiated. However it does take a line which (i) positions a vessel safely north of floating mooring buoys and some indications of shallower water (ii) effectively keeps a vessel within the very deepest part of the river and (iii) permits a simple turn close to Buoy 11 bringing the vessel almost due south towards the starboard side of the river once the bend is passed. It may therefore be regarded as an ideal course to take if there were no other vessels to take into account.

- BURGAN's course appears to have been originally plotted to take her to acquire this 114.40 heading marked on the chart. This appears to have been the course taken by the vessel exiting the port immediately before her.

- Buoy 12 is to the south west side of the river, with Buoy 10 slightly southeast of it in the north east facing part of the river. Buoy 9 is approximately at the farthest east part of the Gupta Crossing, just below the end of the training wall.

- At 0805:55 there was an exchange between the pilots of BURGAN and of another incoming vessel DONG JIANG. They agreed - following a request from DONG JIANG - that they would pass starboard to starboard. Passing port to port was possible, but it was not what DONG JIANG wanted. The prudence or otherwise of this agreement is in issue and forms one of the questions for the Assessors. There was some evidence that such a manoeuvre is not unusual in this location. There was also some evidence (for example in the transcript of the VHS) that the reason for the DONG JIANG's request was that this manoeuvre would permit her to approach her berth most efficiently.

- The Assessors advised, in line with this that:

"The swing would keep his stern in deeper water and utilises the transverse thrust of a right-handed propellor to assist the swing when going astern. It was therefore convenient and reasonable for DONG JIANG to request starboard-to-starboard passing such that she remained on the south side of the channel, but not essential."

- BURGAN agreed to the starboard to starboard passing. At this time BURGAN was heading downriver in about the middle or slightly to port of the navigable channel and was making about 2.7 kts over the ground on a heading of 105.6o and DONG JIANG was well past Buoy No.11. The BURGAN's Pilot ordered her rudder hard to port at 0806:09 and then midship at 0806:24. XPM was just passing the outgoing vessel CAPE FORTIUS at about this time, with each vessel keeping to their starboard side of the channel.

- Meanwhile the third player in the story emerged (at least orally). At 0806:22 and 0806:47 messages were heard on BURGAN's VHF in which SS reported that she had "already departed". This was the only occasion on which SS was heard to communicate on the VHF. There is no plot of her movements at this point, but the exchange and the later emergence of the SS indicate that at about this point, she left the Patenga Container Terminal construction area near Buoy 12 and moved west to east, coming to a halt somewhere in the vicinity of Buoy No 9. It was later remarked on in the investigation at the port that she did so without informing port control. There is also some evidence that (despite her military status) she was for some reason being deployed to carry equipment for the construction of the terminal.

- BURGAN and DONG JIANG were passing each other starboard to starboard at about 0810:33.

- The inevitable result of that manoeuvre was that BURGAN was now on her port side of the river; specifically she was on a heading of 104o and making a speed of 6 knots SOG. Shortly after 0810:05 (C-7½), BURGAN altered course to starboard by about 15° for the next 2 - 3 minutes or so before steadying onto a bearing of 110o. This brought her up parallel to her original planned course but slightly to the north (and port side of the river) to it. From 0811 as she moved past DONG JIANG, BURGAN was to the port side of the centre of the channel, north of her originally planned course and nowhere near the starboard side of the river.

- Although it was suggested in submissions that BURGAN had "steadied" on this course parallel to her original court after and in response to the emergence of the SS, the plots show different; she "steadied" roughly parallel to (but on the port side of) her plotted course immediately after clearing DONG JIANG.

- In the chart below BURGAN is marked in green, with DONG JIANG in blue. The mooring buoys appear as black marks at the bottom of the picture.

Into sight: 0810-0813 (C-6.5-C-4.5)

- At the material time the tide was flooding at a rate of about 3 knots. As already noted, that tidal flow had an obvious effect on the two vessels. XPM, incoming with the tide behind her, was faster over the ground that she would have been through the water; her 8 knots through the water became 11 knots SOG and her 10 knots, 13 knots. Conversely BURGAN, when she increased her speed to 10 knots through the water was only making about 7 knots SOG when she first saw XPM at distance of about 8 cables, when the latter was seen to be proceeding in a north-westerly direction on her port side of the river as she navigated the bend close to Buoy 12.

- XPM says that she saw BURGAN at a distance of 8 cables, bearing about 330o and heading about 110o. Neither the BURGAN or the XPM particularly observed each other on radar.

- From her interpolated VDR data it is apparent that XPM began to turn slowly to port. Her SOG had slowly increased from about 11.5 knots (C-10) to just over 12 knots (C-5). According to the VDR Transcript, XPM ordered a reduction of speed from Half Ahead to Slow Ahead and then to Dead Slow Ahead ready to pass another vessel, the outgoing OCEAN RAINBOW, port to port.

- At about 0813 the XPM passed the vessel OCEAN RAINBOW. She was making 12 knots SOG at the time although her engines had just been reduced to slow ahead. After passing OCEAN RAINBOW, at about 0813:10 her telegraph was put to Slow Ahead and her heading adjusted to port. Her engine was ordered to Half Ahead about a minute later at C-3½.

- It is between C-5 and C-4 that BURGAN submits that she found herself essentially caught between a rock and a hard place, in that the emergence of SS made it unsafe for her to go further starboard and equally unsafe to go to port.

- At C-5 BURGAN's COG was 114.5o and her SOG was 6.9 knots. Having come part way across the channel, so that she was slightly on the southern/starboard side of the channel, she was heading slightly to the port side of the angle of the river's curve. This meant she was heading directly towards Buoy No 11 - which was on the port side of the river as she proceeded. She was parallel to, but on the port side of, the 1140 heading. There was considerable safe space which she could have been occupying further to starboard if she had steered a different course earlier. BURGAN's suggestion that BURGAN was at this point (and at C-4.5) in compliance with Rule 9 and was in the correct position is rejected.

- This was 2 seconds after the SS became visible on BURGAN's radar. At 0813:18 BURGAN's pilot advised Port Control that there seemed to be a Navy Ship near Gupta neighbourhood and asked "Which one is it?". After C-4½ SS began to alter course to port, as was observed by BURGAN's Master.

- According to XPM, SS was seen to enter the channel, to cross ahead of XPM, and then to turn to port in order to proceed upriver. SS moved steadily to port. Her COG was 347.7° to 3150.

- At C-4 BURGAN was more or less directly south of Buoy 13, heading into the sharply curved section of the river and still heading for Buoy 11. SS was roughly in the middle of the navigable channel round the corner of the curve where the channel ran almost north to south and heading towards the northern (her starboard) side of the channel. While she subjectively to BURGAN appeared on BURGAN's starboard bow (as Mr Jacobs KC pointed out in submissions), she was at the same time to port relative to the curve of the river. If both maintained their courses they would both come close to Buoy 11. If BURGAN altered course to starboard (following the line of the channel) their paths would not cross, but they would pass port to port.

- 0813:59 BURGAN's pilot said "It seems to be an army ship, no communication. They don't know how to communicate, how to operate".

- In the chart below XPM can be seen in red at the bottom right. SS is in light grey.

C-3.5 - C-3 (0814:01 - 0814:35)

- XPM's Pilot ordered her engines at Half Ahead at 0814:03. She was at this point steering port relative to the starboard bank, also heading roughly towards Buoy 11.

- At 0814:06 BURGAN's Pilot addressed SS: "Why have you not kept to the left? Can you navigate as you wish? There is a large ship coming behind you. We need to make many preparations. If you operate during movement time, you should always communicate before coming".

- Not having received a response there was then an exchange between BURGAN's Master and Pilot. The Master says that BURGAN is still heading 112o and the Pilot then orders her to steer 115o. Despite the heading reported at this stage BURGAN had actually steadied on a heading of about 110°. She had not slowed. She was not, contrary to the submission made on her behalf, properly to be regarded as on the starboard side in compliance with ColReg Rule 9; if she was at all on the starboard side of the river it was not by much, and it was a long way from "as near to the outer limit of the channel or fairway which lies on her starboard side as is safe and practicable."

- Nor was she "moving gracefully ... across to the starboard side of the river"; as noted above she had ceased to move starboard relative to the line of the 1140 heading some time before. There was no sign of her moving further to the starboard side of the river.

- SS had slowed from 10.1 knots SOG at C-3.5 to 8.7 knots at C-3.

- By this point 3 minutes had passed since BURGAN had passed DONG JIANG.

C-3 - C-2 (081436 - 081535)

- At 0815:03 the BURGAN's Pilot says "Have you seen this Navy Ship, how much have you drifted? Do you have any space here at your place? You need to plan earlier if you wish to come here. You cannot manoeuvre here just as you wish". Then, after the AB confirms that BURGAN is "steady 112", at 0815:14 her Pilot says "See where you have come to, at which place of the Channel. There is a large ship immediately behind you".

- At this point BURGAN was indeed heading 112 - but with the sharp right hand curve of the river starting to play out, she was still heading away from the starboard bank - and still towards Buoy 11. And she was heading towards the area where the effect of the flood tide would be stronger. SS was by now poised between Buoys 11 and 12, more or less in the middle of the channel, though possibly slightly on the port side. Her aspect however continues to be towards the starboard bank; as described by Mr Persey KC "she's not doing it very fast and she's not doing it very effectively, but she is doing as she should be". She was also slowing further: by C-2 her speed was 4.7 knots SOG (allowing for the tide this means she was going very slowly indeed).

- At 0815:21 BURGAN's pilot says "Navy ship, increase your speed and pass quickly. Increase your speed". BURGAN is still heading straight for Buoy No.11, at a speed of 7.6 knots SOG (10.6 knots speed through the water) on a course of 111.8o. At 0815:31 it can be seen from BURGAN's X-Band that SS was acquired as a target a range of 0.270 miles and an eta 0817.

- Meanwhile on board the XPM the focus was on navigating the turn. BURGAN says XPM did not see BURGAN and SS until now. In a reverse of BURGAN's situation, at this point XPM was still steering to port relative to the bank to her starboard, but because of the dogleg effect of the starboard part of the curve, she was heading to the starboard side of Buoy 11 - i.e. coming in for a tight turn to conclude on the far starboard side of the channel beyond Buoy 11.

C-2 - C-1 (081536 - 081635)

- At 0815:41 the BURGAN's Pilot says "Navy Ship, you move to the left. Army Ship, you go to the left".

- At 0815:47 the Pilot of XPM ordered her engines to be put to Full Ahead in order to assist the turn in the following tide.

- At 0815:48 the pilot of BURGAN ordered his vessel to steer "Mid Ship" and very slightly increased speed. At 0815:50 he advised the pilot of XPM to proceed with caution.

- At about 0816 XPM's pilot ordered the AB helmsman to steady. XPM moved closer to the training wall at the Gupta Crossing with a view to passing BURGAN conventionally port to port. BURGAN contacted Port Control at 0816:02 to advise them that "this ship is coming on me. I think it is SHAKTI SHANKAR, isn't it". He then orders a long blast.

- At 0816:06 BURGAN's Master ordered "Long blast, hard to starboard". This was confirmed by her able seaman who, at 0816:10, said "Hard to starboard now". Also, at this time BURGAN's Pilot radioed XPM, saying "please come/proceed as you are moving now".

- BURGAN's rudder is shown at 35o to starboard as at 0816:13. At 0816:13 BURGAN said "Chowdhury Bhai (the pilot of X-PRESS MAHANANDA) please proceed with caution, turning my ship". At 0816:16 (C-1:19) BURGAN radioed "SHAKTI SHANKAR is colliding with me, Control".

- At 0816:19 BURGAN's Pilot orders "Port 20" and then at 0816:21 "Hard to port".

- BURGAN's pilot then orders "Midship" at 0816:33 followed by the order "Hard to starboard" at 0816:35 (C-1). Her rudder achieves hard to port at 0816:37 (C-58 secs).

- At 0816:30, as XPM was approaching Buoy No.11, her pilot ordered "Port 20" and she started to swing to port, following the starboard side of the river channel. There was insufficient room to starboard for XPM to pass BURGAN port to port, and at 0816:40 (C-0:55) her Pilot called BURGAN by VHF and told the Pilot of BURGAN that he was coming hard to port and told her to "Give Hard Starboard, Kayser, Hard Starboard". At 0816:45 (C-0:50) BURGAN's pilot orders "Full hard to starboard".

- The helm of XPM was then put to midships in order to check her rate of turn to port, and her helm was then put hard to port at 0816:56 (C-0:39). At 0816:57 (C-0:36) BURGAN's pilot says "Chowdhury Bhai, going Port to Port, you please come".

- On both videos there is about a 45 second gap between SS clearing BURGAN's starboard side and the collision, as also shown on the MADAS reconstruction.

- At 0817:03 (C-0:32) XPM's Pilot advises that "I am going hard port, you proceed starboard to starboard". At 0817:06 (C-0:29) BURGAN's Pilot says "No no, Chowdhury Bhai, do not come hard a Port, I will go port to port with you". At 0817:10 (C-0:25) XPM's Pilot responds "not port to port, starboard to starboard only, I have no other way" and at the same time the Master of BURGAN is recorded as saying "We cannot go starboard to starboard".

- Very shortly before collision, at 0817:26 the engine of XPM was put to stop and her rudder was put hard to starboard.

- The XPM and BURGAN collided at the Gupta Crossing at about 0817:35 in a position well to XPM's starboard side of the river at the very edge of the buoyed channel. The collision was almost head on, with the port bow of XPM colliding with the starboard bow of BURGAN. The XPM was heading about 316o at collision and the BURGAN about 125o. The XPM was making about 13.3 knots over the ground (10.3 knots through the water) and the BURGAN was making about 7.7 knots over the ground (10.7 knots through the water).

- The respective positions of the vessels appear below:

The Parties' Respective Cases

- The Claimant says quite simply that this collision was caused by BURGAN's failure to stay on her own starboard side of the river. Had she done so, then there would have been no collision between the vessels and nor would there have been any risk of a collision between BURGAN and SS.

- The Defendant's case against XPM is that while SS probably bears the majority of the blame for the incident XPM was also at fault in that she was proceeding too fast and should have been more to her starboard side of the river. The Defendant submitted that BURGAN might have been at fault, but those faults were actually not causative of the collision. In particular it was said that the only "What if" scenarios ventilated relate to the time from after the DONG JIANG passage and that thereafter BURGAN had almost regained her course line - and that she would have done so but for the SS. The Defendant further submitted that BURGAN was confronted with an unenviable dilemma: if she continued to move to starboard, she risked a close quarter situation/collision with SS (whose navigational intentions were not readily apparent); but an alteration of course to port might embarrass inbound traffic such as XPM and is an alteration which a mariner would not in any event make except in a dire emergency.

- As noted in the heading, the trial of this matter was conducted over 2 days. Owing to the very good amount of common ground which had emerged on the facts and the evidence available, the trial estimate of three days was not fully used. No live evidence was called.

- I should note my gratitude to counsel for the skill and clarity of their submissions. Both sides' counsel provided me with clear and helpful skeletons with recitations of the common ground on the facts which have much assisted in the preparation of the judgment, and both also amplified and supplemented these with clear and expert oral submissions.

- In this context one further point should be made: I believe this case to be the last appearance as an advocate of XPM's counsel, Mr Lionel Persey KC. On this occasion I can usefully combine my thanks for his submissions in this case with a wider thanks owed to him from many judges of the Admiralty and Commercial Courts over the years.

- Both counsel co-operated to narrow, if not to agree, the questions to be put to the Elder Brethren who sat with me as Assessors. Both also provided valuable input on the responses of the Assessors. The procedure adopted for obtaining the Assessors' advice was out by Gross J (as he was then) in The Global Mariner and the Atlantic Crusader [2005] EWHC 380 (Admlty) at [12]-[17], especially [14]. Following receipt of fairly lengthy submissions on the Assessors' initial advice I referred those submissions in their entirety to the Assessors. They concluded that, except for a few comments of clarification, the respective parties comments either support or question the responses in broadly equal measure and they therefore limited their response to some detailed comments on particular issues (safe speed, SOG/STW, DONG JIANG and BURGAN in relation to SS), referred to below, which I did not consider required further reference to the parties.

- I am extremely grateful to Captain Gobbi and Commodore Dorey for their expertise and for their essential and wise counsel.

- This collision essentially occurred because of two co-operating factors. The first is that BURGAN was to port of the centre of the buoyed channel and the second is that, faced with two oncoming vessels, she reacted as she did. There is need to evaluate whether she could and should have been elsewhere, or done differently. But there is also a need to evaluate the extent to which the other vessels were themselves at fault. In respect of all faults identified it is also necessary to bear in mind whether those faults are causative.

- There are two main respects in which BURGAN criticises XPM. The first is as to the state of her look out (Rule 5). BURGAN focusses on two points:

1) The VDR Transcript does not contain any relevant observations or discussions by XPM's Bridge Team as to the other vessels until 0816:12 which illustrates that XPM's visual, aural and radar lookout was extremely poor;

2) The only target ever acquired by XPM was Target 12. This Target was acquired at the anchorage at or before 0717:42 and no longer of any relevance once XPM was leaving the anchorage. It is thus clear that XPM made no attempt to acquire either vessel.

- The Assessors were asked about this. Their response was:

"XPM should have observed BURGAN:

(a) By AIS, on approach to entering the river and by listening to VTS traffic transmissions.

(b) By radar, at approximately 1 mile. The ship's radar sets were set to an inappropriate range and not continuously observed to detect moving targets. Longer range detection may not have been reliable due to the interference of land on the peninsular.

(c) Visual detection is line-of-sight, and the Master/Pilot should have observed movement as the river line opened. Therefore approximately 1 mile would have been reasonable.

As a general comment, close attention should have been made to the departure broadcast of BURGAN and use made of VTS.

XPM should have observed SS

(a) By radar at 1 mile.

(b) Visually at 1 mile."

- It is therefore fair to say that XPM's look out was imperfect. She should have seen the other vessels somewhat earlier than she did. It is however hard to see how this was causative of the collision in any way. There is no case that XPM should have actively done anything other than reduce speed (the next point). For the avoidance of doubt I conclude that nothing XPM did or could sensibly have done would have impacted on the key exchange between BURGAN and SS which resulted in BURGAN coming hard to port, and effectively placing herself in a position where to avoid SS she rendered a collision with XPM almost inevitable.

- The main focus of BURGAN's criticism is XPM's speed (Rule 6). It was BURGAN's case that XPM's speed was too great, being a SOG of between 11.36 and 13 knots. The impression sought to be conveyed was that "she was bombing up the river at 11.5 knots without any regard for what she was going to encounter at the Gupta Crossing".

- BURGAN's case was in essence that XPM should have been going no faster than 8 knots (or at most 10 knots) over the ground, that 5 knots was actually sufficient to maintain steerageway, and that XPM should have slowed after seeing SS and BURGAN's positions. There were of course refinements to this position as to the steps which XPM should have taken as to speed at different points in the river transit. There were also a number of "what if" possibilities canvassed.

- So far as this is concerned, the bulk of this criticism is in my judgment misconceived. The points made by BURGAN about the warning on the Admiralty chart and the potential presence of small fishing vessels are valid; but they do not go to the appropriate speed. While it is true that the passage plan indicated a speed of about 8 knots and that may well have been a speed over the ground, that is not determinative as to the appropriate speed, given the conclusions expressed about the passage plan. Nor is XPM's bridge poster, which referred to "minimum speed to maintain course, propeller stopped" of 5.5 knots. Some of this argument appeared to be predicated on a theory about controllable pitch propeller, which was said to allow "feathering" with no or minimal propulsion. This was not supported by the Assessors who considered that a controllable pitch propeller in fact made things more difficult: "a reduction of speed will reduce steering sensitivity, particularly with a CPP where the water flow can be disrupted by the angle of the blades when reducing propeller pitch". I conclude therefore that there is nothing in this point to assist BURGAN.

- At the heart of the issue lies the challenge which faced XPM, navigating towards a sharp bend and in the flow of the very considerable tide. There are two key navigation/seamanship aspects embedded within this. The first is the effect of the flood tide. Because of the direction of the tide, if XPM was to maintain any degree of control she had, in effect, to be making considerably more speed than the tide. The second factor is the way the tide and flow of the river impacted on the very particular geography of the turn in the river.

- As the Assessors put it:

"The minimum safe speed through the water is that which is sufficient to maintain steerageway. That is to create enough flow past the rudder to have effective directional control of the vessel.

The vessel will however, set into the bight of the bend of the river due to the tidal flow, which can only be counteracted by the direction or heading of the vessel through the water. It would be prudent in the circumstances to increase the flow of water over the rudder just before the bend in the river, in order to ensure good steerage way through the turn. This is not to increase speed as such, but to further improve control through the turn, where in addition to safely navigation the large turn, the rate of tidal flow on the outside of the bend could reasonably be anticipated to be faster than the steady flow on a straight section of the river, coupled with the anticipated set into the bight. ...

It is important to note that any increase of speed would increase steerage sensitivity, whereas a reduction of speed will reduce steering sensitivity, particularly with a CPP where the water flow can be disrupted by the angle of the blades when reducing propeller pitch....

The speed of the current in the bight of the Gupta Crossing would have been much higher than the average, whereas the speed of flow to the south, towards the airport peninsular would have been much less (perhaps even with a counter current in vicinity of the southern jetties). This is the normal situation on tight river bends and would have been well known to the pilots."

- The Assessors also concluded on the reasonable range of safe speeds: "although a higher speed may be warranted on entering the river, once proceeding along the river, a reasonable safe speed through the water could have varied from 5.5 knots to 7.7. knots."

- The net result of the Assessors' views on the speed issue, as applied to the facts, leads to the conclusion that XPM was predominantly proceeding within a safe speed range. In effect XPM had to maintain a considerable speed in order to maintain control, and acting entirely prudently would further increase that speed in the immediate vicinity of the turn so as to counter the effects of the tide within that constricted area. It must, in my judgment, also be borne in mind that as to the latter factor, the precise effects could not be accurately anticipated. Erring on the side of caution to some extent would therefore be no error at all.

- The one respect in which the assessors consider XPM can be faulted is in relation to not acting once BURGAN was detected. Their view is that:

"as soon as the BURGAN was detected as encroaching onto the wrong side of the river, and with the prospect of an imminent collision, speed should have been reduced as fast as possible. Emergency full astern. To take off the speed in the final moment may have resulted in the vessel being set onto the training wall between Buoys 11 and 13. However, as a matter of seamanship this would have been a better option than a head-on collision at speed with another vessel, while any reduction of speed achieved in the final moments would likely have some degree of positive effect, in reducing the extent of damage."

- Their response to the submissions on their initial advice, also indicated that the question was not so much one of speed but contingent pre-planning:

"should it have been determined by either vessel that it was undesirable to meet at the turn, and positive action should have been taken through clear communication between the respective vessels, and VTS, to deconflict the point of meeting to a more suitable location."

- I do therefore conclude that in point of speed XPM was not generally at fault, but it may be that at the very last moment XPM was at fault as regards speed. However the fault did not cause the collision; it only may have had some impact on the amount of damage sustained. At the same time, I do bear in mind the point made by XPM in response to the Assessors' advice that slowing and losing steerage way carried a risk of a collision at a broader angle with BURGAN with greater damage. I also note BURGAN's submission made in writing that the orthodox approach of the Admiralty Court is to disregard the final couple of minutes before the collision.

- BURGAN did contend that there were other faults on the part of XPM, but very much more faintly. To the extent that these were seriously pursued I reject them. In particular, as to XPM's navigation, some criticisms were made of the course steered by XPM. Although at some points XPM was not hugging the starboard bank, and steered to some extent to port, that was in the context of positioning herself to take the sharp turn at the Gupta Crossing and was such as to position her to embrace the starboard bank on the turn. That positioning impeded no-one and had not the slightest bearing on the actions of either BURGAN or SS.

- I note that the contemporaneous view of the BURGAN's Master in the Bangladesh proceedings was simply that the cause of the collision was "Military boat interrupted the safe passage of my vessel". No blame was cast on XPM for the occurrence of the collision.

- XPM submitted that BURGAN failed to keep to the outer limit of her starboard side of the channel. Simply looking at BURGAN's position she plainly was not as far to starboard as she could have been absent the other vessels. This prima facie engages Rule 9(a) of the ColRegs which provides as follows;

"A vessel proceeding along the course of a narrow channel or fairway shall keep as near to the outer limit of the channel or fairway which lies on her starboard side as is safe and practicable".

- There is no issue that River Karnaphuli is a narrow channel and that Rule 9 therefore applies.

- It is also established that breach of this rule is a serious fault: The Maritime Harmony [1982] 2 Lloyd's Rep 400 at 403, per Sheen J.

"I was invited by Mr. Clarke to make a precise measurement of the channel and then to say that any ship which is just on its correct side of the imaginary centre line is complying with its duty. In my judgment that is not the correct approach to problems arising out of navigation in narrow channels. A prudent navigator knows that his ship is on its correct side of a narrow channel without necessarily knowing precisely where the centre line runs. He knows this because he keeps as near to the outer limit of the channel as is safe and practicable."

- See also the Nordlake v The Sea Eagle [2015] EWHC 3605 (Admlty) [2016] 1 Lloyd's Rep 656 [149] per Teare J: "Breaches of the obligations imposed on ships in certain defined situations by the Collision Regulations will usually be regarded as seriously culpable. One such rule is the narrow channel rule."

- In the present case BURGAN was in the centre of the navigable channel when she came off her berth. She remained either in the centre of the channel or to her port side of the channel at all material times thereafter. The question was whether she was at fault in not doing so, or whether events meant that her location was in practice as far to starboard as she could get.

- There was much debate about whether the Assessors should be asked any questions about anything which occurred before C-4.5 and the effect of the "what if" scenarios having been limited to ones from that point in time. The starting point for this debate is that if BURGAN had come to starboard after she had come clear of the berth the problem would never have arisen - she would have proceeded well clear of all oncoming traffic.

- In my judgment this was a rather sterile debate, because, certainly so far as the DONG JIANG passage is concerned, it is clear that that event was not itself causative.

- It does however form a backdrop to the situation in which BURGAN found herself and the question of what if any fault there was on her part. As such it comes into the scope of the court's consideration when looking at the faults of navigation and assessing their respective seriousness judged against the navigation as a whole.

- The Assessors considered that while it was certainly reasonable for DONG JIANG to ask, it was not reasonable for BURGAN to agree to a starboard to starboard passing. The reason is that this placed BURGAN on the wrong side of the river (i.e. to the north) and at a relatively short distance from a significant turn.

- The significant point here (and the reason why BURGAN's criticisms of the Assessors views is misplaced) is the Assessors' views that, having agreed to this approach, the manoeuvre obligated the BURGAN to rectify the issue, without delay, by regaining the starboard side of the channel in compliance with Rule 9 (a). An assessment of the reasonableness of BURGAN's decision has to include a consideration of the consequences she would have to take into account as to the progress of her transit; for DONG JIANG the matter was much simpler - she had no downstream complications to assimilate.

- This conclusion is given more weight by the Assessors' view that BURGAN should have observed XPM by AIS prior to leaving the berth. They noted that it would be normal practice to observe, enquire and verify (through VTS) other river movement before moving from a terminal. Knowing that XPM was coming, and knowing the configuration of the turn, it was therefore incumbent on BURGAN to proceed as rapidly as she might to the starboard side of the river.

- There was no issue about whether this could be done. It was clear that there was still more than sufficient time after passing DONG JIANG for BURGAN to come to her starboard side of the channel. This she emphatically did not do. Instead of keeping "tight to the southern buoy line on the starboard side of the channel in accordance with Rule 9(a) ... [with] heading ... such that he maintained this position tight on his starboard side of the river" adjusting in anticipation of a strong northerly element of the set around the bend at the Gupta Crossing, the pilot of BURGAN maintained a course for the No.11 Buoy, the effect of which (from the place where she parted company with DONG JIANG) was to bring her more and more towards her port side of the channel, rather than to her starboard side of the River.

- It is not the case (as was submitted for BURGAN) that "BURGAN altered course to starboard in accordance with Rule 9 (and her course line). Indeed, BURGAN's radar shows that she had almost resumed her course line by about C-4¾ or 4½". BURGAN's proper course after the DONG JIANG passage should have been one which would bring her properly to the starboard side of the river. While there were mooring buoys the suggestion that there was no safe space is not one which is supported by the evidence, as already noted.

- The impression, looking at the vessel track, was that before leaving the berth a heading had been calculated based on the original starting point, and without anticipating the effects of the DONG JIANG passing, and that having permitted that unconventional passing, those in control of BURGAN did not re-iterate the plan, but simply reacquired the originally planned heading. That, of course, left BURGAN very much further towards the centre of the stream than she should have been.

- The Assessors opine that another factor may have fed into this approach, namely that the pilot "did not appear to anticipate the strong northly element of the set around the bend at the Gupta Crossing." That would seem to chime with the submission made for BURGAN that "the reason why the course line is just to starboard of the heading may well be the effects of the tide on the vessel 's port bow. So moving her course made good just to starboard of her heading."

- In one sense the precise thinking or causation behind the approach taken is irrelevant. BURGAN was under an obligation to get back to her starboard side of the river. She could have steered a different course - one headed towards Buoy 12 rather than Buoy 11 - which would have had that effect, regardless of the northly effects of the tide. She did not do so. She must or should have appreciated that the course she was steering was not bringing her to the starboard side of the channel, but she did not - at any point in the succeeding minutes - take steps to counter this. This was a critical component in what was to follow. It was not directly causative, but it was a link in the chain or errors and faults which led to the collision. Although BURGAN was right to say that XPM did not explicitly plead a fault prior to C-4.5 and that the "what if" plots focussed on the later time line, the wider picture must properly form part of the Court's consideration.

- I reject the submission that BURGAN could not take her correct ground because of the SS. BURGAN placed much reliance upon a document produced by the Chittagong Port Authority as part of its investigation, which states that "as Shakti Sanchar came very close to MT Burgan, the later vessel had no room for altering to starboard thus collision with MV Express Mahananda could not be avoided ...". That comment is one which has no status for this court's purposes. The material available to the Port Authority is unclear. This claim must be decided conventionally by reference to the material before the court.

- On the basis of that material, for the reasons given, I conclude that regardless of the position prior to C-4.5, there was ample time from C-4.5 for BURGAN to clearly signal in appropriate ways that she was in fact proposing to comply with ColRegs Rule 9. If by C-4.5 it was not necessarily wise to do so by an alteration of course "large enough to be readily apparent to another vessel observing visually or by radar" (rule 8(b)), it could have been done by slowing very considerably, combined with appropriate audible signals. That would also have improved the chances of ascertaining that SS was not (as BURGAN submitted, and may have reactively thought) on or heading to her port(BURGAN's starboard) side of the river.

- But as indicated above there was also time before C-4.5 when BURGAN could and should have been doing a much better job of navigating to her correct position - or signalling her intent to do so by making large alteration of course which could then have been supplemented by significant slowing and/or audibly signalling.

- So I conclude, in line with the Assessors' advice, that BURGAN was at fault in the line that was taken in steering the vessel.

- That Rule 9 error was compounded by the lack of a proper lookout (via the various means available to the vessel and her crew). The Assessors concluded that:

1) BURGAN should have observed XPM by AIS prior to leaving the berth. It would be normal practice to observe, enquire and verify (through VTS) other river movement before moving from a terminal;

2) BURGAN should have observed XPM by radar between 1 ½ and 1 mile by radar. This would require the appropriate range and a dedicated observer from the bridge team;

3) BURGAN should have detected SS by radar at 1 mile by careful and continuous observation on the appropriate ranges on both X and S Band radar sets. Perhaps enhanced by ARPA;

4) BURGAN should have observed both vessels visually at approximately 1 mile when in direct line-of-sight.

- The short point is that BURGAN had various means of assessing the location of the other vessels and that she either did not use them at all, or used them too late. Had BURGAN used her means of maintaining a look out appropriately then she would have appreciated somewhat earlier than she did that SS was coming upriver, that SS was being followed by XPM, and that it was inevitable that she would pass them either before or at the Gupta Crossing. That would have given her more vital time, to make appropriate decisions and to take them. Because of the absence of appropriate lookout/use of monitoring BURGAN was well within the one mile distance when BURGAN's Master took action at 0816:06 ordering his vessel hard to starboard. That order was far too late.

- The absence of lookout issue also feeds into the navigation issue, as subsequent steps by BURGAN smack of panic (particularly when read with the transcript from the bridge):

1) The appropriate action taken too late was in any event countermanded by the Pilot's port 20 and hard to port orders;

2) BURGAN compounded this breach by coming yet further to her port side of the channel on a course of 091.0o before turning back to starboard.

Rule 6

- There was also a yet further compounding error in relation to speed. Until 0816 BURGAN was proceeding at about 7.4 knots over the ground (10.4 knots through the water) and then her speed gradually increased to about 7.8 knots. Unlike XPM, BURGAN was in a situation where she was perfectly controllable at a low speed, giving her crew ample scope to reduce speed considerably. Because she was stemming the tide she could have been held steady or steered effectively while at Dead Slow or even at stop. I therefore conclude that once SHAKTI SANCHAR was spotted BURGAN was at fault in not slowing or even stopping. As the Assessors put it, BURGAN:

"had every opportunity to maintain control while reducing speed. In light of the presence of the SHAKTI SANCHAR(SS) and in the knowledge of the inbound XPM, it would have been seamanlike given the tidal conditions, that he should have slowed or stopped (over the ground) to allow the inward ship (XPM) a clear run around the bend while providing clear intentions and more time to resolve the issue of SS.

BURGAN could even have placed an anchor down to hold the bow while awaiting the passing of the XPM. This being an action to enhance control for a limited period, conscious of Rule 9(g), to avoid anchoring in a narrow channel."

- In response to comments by the parties on this, they supplemented their view thus:

"In relation to anchoring, we do not imply that Burgan should anchor and lay out a full scope of cable. This would not be advised and as 'the circumstances of the case admit' should be avoided under Rule 9 (g). Speed, while heading into the tide, would be the most effective element (while stemming the tide) in maintaining control while allowing more time to assess the situation or to adjust the point of meeting. However, we point out that dropping an anchor 'underfoot' or with a very short scope, while maintaining control of engine and rudder is a recognised means of holding position into a tidal stream."

- The short point is this: BURGAN should have reduced speed as soon as she saw SS and was unsure as to her movements. That was the approach consistent with ColRegs 8(e) "If necessary to avoid collision or allow more to assess the situation, a vessel shall slacken her speed or take all way off by stopping or reversing her means of propulsion."

- Again this fault segues into another fault on BURGAN's part. That is the failure to engage with SS. Rule 34 provides for the use of the appropriate sound signal.

- The only way in which BURGAN sought to communicate with SS was via the VHF. This she did repeatedly, and unsuccessfully. Again, the communication is redolent of panic rather than ordered or constructive thought. Nor can it be said that the pursuit of VHF communication was without consequences. Time was spent with the pilot endeavouring to get his point of view across when the time would have been better used ensuring that his own vessel came to starboard and that her speed was reduced until she had passed SS and also communicating in a way which was prescribed by the ColRegs, and must have come to the attention of the SS.

- As soon as BURGAN was in any doubt as to the intentions of SS she should, in accordance with that rule, have sounded one short blast on her whistle meaning "I am altering my course to starboard" and then, if still in any doubt as to the intentions or actions of SS, to follow this up by giving at least five short and rapid blasts on the whistle.

- I note that the Court has deprecated the use of VHF as a means of agreeing a course of navigation which is contrary to the ColRegs: see The Mineral Dampier [2001] EWCA Civ 1278 [2001] 2 Lloyd's Rep. 419 at [35]-[39], per Lord Phillips MR; The Samco Europe [2011] EWHC 1580 (Admlty) [2011] 2 Lloyd's Rep 579 at [55], per Teare J. While those authorities do indicate that using the VHF can be appropriate, they make clear that reliance on it is not safe. I do not read it, as I was urged to do, as being limited to a situation where vessels are passing or approaching a close quarters situation. That is just one example of a situation where time is tight and a hierarchy of steps to be taken may be important. The facts here illustrate precisely how vital time was lost with the pilot of BURGAN hurling reproaches at SS, rather than taking steps which were safer bets to make himself understood and avoid catastrophe.

- Nor was it a case of use of VHF as a last resort; rather the use of VHF was, as Mr Persey KC submitted, the only resort. In reality it ended up absorbing time which might otherwise have been spent (i) making an unequivocal course change (ii) slowing down markedly and (iii) giving the appropriate signal.

- In circumstances where SS was acting unexpectedly and initial communication brought no response, it was a serious fault on BURGAN's part not to signal her intentions unequivocally using the appropriate sound signal.

- Valiant attempts were made by Mr Jacobs KC to resist these conclusions on behalf of BURGAN, but they are inescapable. As to the points made in submission which have not thus far been dealt with:

1) There was some suggestion that BURGAN was constrained by her draft not to navigate further to starboard (i.e. that the 110 heading was the most starboard safe course). This derives from a chart deployed by the experts Brookes Bell in modelling, based on soundings at a later date, which appears to show a patch of 5m depth. There was, however, no such marking on either of the contemporary sources used by the pilot at the time. The ECDIS chart shows patches of 7.6 and 7.9. Further the depth of the river would of course be affected by the tide which was in flood, adding quite enough depth to render such soundings unproblematic. And indeed if BURGAN had headed more sharply to starboard after passing DONG JIANG she could have been to the south of these patches and in deep water;

2) There was also a suggestion that BURGAN was constrained by the position of number 12 Buoy which it was suggested was not positioned as marked but slightly to the north of its marked position - effectively pushing BURGAN away from the starboard bank and once SS's position was taken into account giving her no room to move to starboard at C-3.5. This was not a pleaded point and was raised on the basis of overnight instructions at the end of the hearing. It was also contrary to the agreed MDAS reconstruction and the ECDIS report. Further it did not on examination seem to be a tenable point;

3) There was also a submission as to the relevance of "virtual AIS buoys" some way in from the starboard bank. Again, ingenious as this point was, it added nothing as the "virtual AIS" seemed to do no more than mark the limits of the mooring buoys, which had always had to be taken into account;

4) The DONG JIANG passage was imprudent; but I accept the submission that it was low in culpability and was not directly causative. Thus it adds very little to BURGAN's fault.

The fault of SS

- BURGAN says that the majority of the fault is that of SS and was down to erratic and dangerous navigation. She has pleaded that the SS was at fault in the following respects:

1) Failing to keep a proper lookout;

2) Failing to make any proper use of their radar and/or failed to act upon its indication in due time, properly or at all;

3) Proceeding at excessive speed (particularly given the congested nature of the waters) and failed to ease, stop or reverse their engines in due time or at all;

4) Failing to keep to the starboard side of the River (a narrow channel within the meaning of Rule 9 or the Collision Regulations);

5) Failing to make proper use of VHF;

6) Failing to keep clear of BURGAN;

7) Failing to appreciate that there was a risk of collision and/or take any or any substantial action to avoid the collisions;

8) Failing to give any sound or light signals;

9) Failing to comply with Rules 2,5,6,7,8,9 and 34 of the Col Regs.

- XPM submits that while some fault is doubtless attributable to SS one cannot be sure of some of the points raised against her in the absence of any evidence from SS; that SS's fault, if any, was not causative. Alternatively, overall BURGAN's fault was 4 times greater than that of SS.

- The common ground as to faults on the part of SS is that she was at fault in:

1) Failing to keep to the starboard side of the River in breach of Rule 9. She kept in about the centre of the River, although was making her way very slowly to her starboard side. She should have gone to her starboard side near to the outer limit of the buoyed channel. While some of the criticism by BURGAN is not fair (in that SS was moving in real terms to starboard following the river round its curve, and not, as was submitted, to port), she, like BURGAN, was at fault in not moving to starboard earlier and more emphatically;

2) Not making any use of her VHF - it may have been switched to another channel or off when BURGAN was attempting to contact her. It was not suggested that she should have used the VHF in the way in which BURGAN's Pilot did;

3) Failing to give the appropriate, or any, sound signals. A fault the more serious if no use was being made of VHF.

- I also conclude that it is a permissible inference that SS's lookout was defective, either in execution or in reasoning from the results; in that if a proper lookout had been maintained and used it is highly unlikely that SS would have executed the manoeuvre which she did at this point in time.

- As for the submission by BURGAN that SS was at fault in proceeding too slowly - in that had she sped up and got way across to the western side of the river, I do not find this persuasive. SS, having wrongly darted out into the river was confronted by a puzzle. Her action in slowing to evaluate it was conventional and not wrong and was consistent with ColRegs 8(e) "If necessary to avoid collision or allow more to assess the situation, a vessel shall slacken her speed or take all way off by stopping or reversing her means of propulsion." It may be that with hindsight speeding up would have had a better result; but failing to do so was not a fault.

- There is however a point which does follow from this: it is the knock-on effect of delay. BURGAN pointed out that by proceeding as she did SS put herself in the position where there were risks of collision both as regards BURGAN and XPM. By acting when she did and then hesitating SS ran the risk of making the starboard side of the river at the same time as XPM. A better course once the difficulties were appreciated would seem to have been to abort the transit rather than pressing on and exacerbating the difficulties.

- This is a case involving the negligent navigation of three vessels, only two of which are before the Court.

- Section 187(1) of the Merchant Shipping Act 1995 provides;

"... Where, by the fault of two or more ships, damage or loss is caused to one or more of those ships, to their cargoes or freight, or to any property on board, the liability to make good the damage or loss shall be in proportion to the degree in which each ship was in fault ..."

- The approach to be taken to the task of apportionment in cases where three or more ships are alleged to be to blame was set out by the House of Lords in The Miraflores & The Abadesa [1967] A.C. 826. The task of the court is to decide whether the collision was caused by the fault of two or more vessels and, if it concludes that it was so caused, to apportion liability by reference to each one of them.

- The vessels Miraflores and Abadesa collided in the river Scheldt and blocked the channel. The vessel George Livanos then grounded whilst trying to avoid the collision. An action was brought by the owners of the Miraflores against the owners of the Abadesa in respect of the collision. The owners of the George Livanos brought an action against both of the other vessels in relation to the grounding. The claims were heard together and eventually reached the House of Lords on appeal. Lord Morris, after quoting section 1(1) of the Maritime Conventions Act 1911 (which is in materially identical terms to s.187(1) MSA 1995), held at pp.841E-842:

"... The section calls for inquiry as to fault, and inquiry as to damage or loss, and inquiry as to causation. ...

Consequently three inquiries were involved. To what extent as a matter of causation did the fault of the Abadesa bring about the grounding of the George Livanos? To what extent as a matter of causation did the fault of the Miraflores bring about the grounding of the George Livanos? To what extent as a matter of causation did the fault of the George Livanos bring about her grounding? The liability to make good the damage or loss caused by the grounding would be in the proportions shown by the answers to those questions ...

... As applicable in the present case, once it was established that there was fault in each one of the three vessels and also that the damage or loss of the George Livanos was caused to some extent by the fault of each one of the three vessels, then it became necessary to apportion the liability for the damage or loss by deciding separately in reference to each one of the three vessels what was the degree in which the fault of each one caused the damage or loss to the George Livanos. The process necessarily involved comparisons and it required an assessment of the inter-relation of the respective faults of the three vessels as contributing causes of the damage or loss. ..."

- Lord Pearce said at pp.846-847:

"... To get a fair apportionment it is necessary to weigh the fault of each negligent party against that of each of the others. It is, or may be, quite misleading to substitute for a measurement of the individual fault of each contributor to the accident a measurement of the fault of one against the joint fault of the rest ...

... It follows, therefore, that I entirely agree with the observation of Winn L.J. that the liability of each vessel involved must be assessed by comparison of her fault with the fault of each of the other vessels involved individually, separately and in no way conjunctively ..."

- It was decided by Teare J that the same approach to the task of apportionment is applicable where one or more of the vessels at fault is not before the Court: The Nordlake v The Sea Eagle [2016] 1 Lloyd's Rep. 656 at [144]-[148].

- In determining whether a party is at fault it is established that both culpability and causative potency must be taken into account: see The Nordlake at [149] and Apportionment of Liability in British Courts under the Maritime Conventions Act 1911 (1977) 51 Tulane Law Review 1025 at 1031-1032, per Brandon J.

- Reliance was also placed by both parties on the Bywell Castle [1894] 4 PD 219 with each, from its own perspective, praying in aid the passage at p 223 where James LJ states that where one ship has by wrong manoeuvres placed another ship in a position of extreme danger, that other ship will not be held to blame if she has done something wrong, and has not been manoeuvred with perfect skill and presence of mind.

- Although I was referred to these various loci classici in respect of apportionment, I suggested to counsel (and they accepted) that regard should also now plainly be had to the recent Donald O'May lecture by Sir Nigel Teare "Apportionment of liability for damage caused by two or more vessels: is it a simple or a complex exercise?" LMCLQ 2023 p 225. In that lecture he both considers the earlier sources and draws on his practice at the Admiralty Bar and his experience as Admiralty Judge. It is (as he himself describes the article of Brandon J) "a most authoritative account by a most distinguished judge."

- In particular Sir Nigel says the following:

"Apportionment is therefore a crucial part of collision litigation and must, whether it be simple or complex, be conducted carefully...

Let me begin with what you should not do. As has been said in several cases, you do not count the number of faults. The number is not decisive. What matters is their nature and quality, which must be assessed by reference to the two elements of fault: causative potency and blameworthiness...

Sir Henry Brandon explained that causative potency had two aspects: 'The first aspect is the extent to which the fault concerned contributed to the fact that the collision or other casualty occurred at all. The second aspect is the extent to which the fault concerned contributed to the damage or loss resulting from the collision or other casualty.'

... the causative potency of the vessel which fails to react to a situation of danger which has been created by another vessel will usually be regarded as less than that of the vessel which created the situation of danger. ...

the ultimate enquiry in collision litigation is as to the relative causative potency and blameworthiness of each vessel....

When comparing the faults of one vessel with those of another, the court must inevitably form a value judgment not only about particular aspects of the vessels' navigation but also about the vessels' navigation as a whole...

How does one reach the ultimate decision as to relative degrees of fault expressed in terms of fractions or percentages? The court usually asks itself how many more times ship A was at fault than ship B..."

- I have kept that guidance (and the other guidance in that article) fully in mind in carrying out the exercise which follows.

- XPM submitted that the culpability and causative potency of BURGAN's faults were overwhelming and that her failure to comply with Rule 9 coupled with her deliberate decision to go to port can legitimately be viewed as the sole effective cause of the collision between her and XPM. XPM also submitted that:

1) If SS's faults had some causative potency then BURGAN was at least 4 times more to blame than SS;

2) XPM was not guilty of any navigational faults and certainly not of any that were culpable or which had any causative potency.

- BURGAN's submission was strikingly different. It was urged that fault lay predominantly with SS and otherwise with XPM, with BURGAN being essentially faultless.

- Ultimately it is clear from the analysis above that BURGAN was much at fault, in a number of serious ways, which interacted with each other and were causative. Specifically:

1) BURGAN's failure to regain the starboard side of the river (after imprudently agreeing to the DONG JIANG passing) was the originating fault. This involved an apparently deliberate decision to steer for Buoy 11 rather than altering course to reflect the fact that she was further to the port side of the river than she should have been. BURGAN had plenty of time to come on to her intended track before SS had rounded the bend, and she had plenty of time to come to starboard off her intended track;

2) This failure was compounded by the lack of proper lookout which meant that her actions were reactive rather than considered;

3) BURGAN's failure to engage SS as quickly as possible in an effective manner (i.e. by whistle in accordance with Rule 34);

4) BURGAN's failure, once the SS was sighted, to reduce speed considerably until a safe protocol was established. As already explained this was more than possible as the vessel stemming the tide, she could maintain control of her rudder at a dead slow or stop. Instead her pilot simply carried on the wrong course and at the wrong speed.

- SS was also significantly at fault, and that fault had a real causative impact. In the decision to cross the river at this precise time (failure to maintain a lookout), the ambiguous line taken (failure to observe Rule 9 or signal by steering under Rule 8) and determined failures to communicate, SS was a key part of the ultimate collision and a not insignificant one either in culpability or causative potency.

- XPM was not entirely faultless, in that she did not keep as good a lookout as she should have done and that she failed to slow once the difficulty of the situation with BURGAN and the danger of collision became apparent. But one aspect of her fault was not causative, and the other (not slowing as the final events unfolded) only even arguably goes to the extent of damage. This is not a simple excessive speed fault correlating with a "seriously culpable" conclusion. In addition that fault at least to some extent falls within the ambit of the principle from pp 847-8 of the Miraflores that in general someone who has a crisis thrust upon him is to be seen as less at fault than a person who by their negligence creates that crisis (and this Court's tendency not to rest on last minute actions). Viewed fairly it is hard to see how any of these actions can be said to have any identifiable causative potency.

- BURGAN's faults were therefore not just more numerous, they were more important and more causative than the faults of the other vessels.

- It follows that I conclude that BURGAN was the most at fault. I apportion 65% of the fault to BURGAN. SS was also at fault, and very much more than the 25% of BURGAN's fault urged by XPM. I conclude that 35% is the appropriate apportionment of fault to SS.