- Damages inquiries are rare in intellectual property cases. This case may help explain why. What ought to have been a comparatively simple exercise of trying to put the Claimants into the position they would have been in had the infringement not occurred became marred in detail and side issues. This judgment is therefore of necessity longer than I would wish.

- The Claimants (by which I mean the First and Second Claimants, the Third Claimant being in liquidation and taking no part in proceedings) sell bandage and bodycon dresses and other garments under the brands House of CB and Mistress Rocks. House of CB competes with the Defendants (where it is necessary to distinguish between them I will do so), who also sell bandage and bodycon dresses and other garments, but under the brand Oh Polly. 15,393 Oh Polly garments sold by the Defendants infringed unregistered design rights owned by the First Claimant. The Claimants therefore sought damages under three heads:

(a) their lost profits on garments which, but for the Defendants’ sales, would have been made by the Claimants;

(b) a reasonable royalty on the Defendants’ sales not covered by (a) above; and

(c) additional damages pursuant to my earlier finding that the Defendants’ infringement was flagrant.

- Before me, the parties referred to (a) and (b) above as “standard damages” and (c) as “additional damages”. The Defendants denied that lost profits damages were payable at all. The Defendants accepted that a reasonable royalty was payable, but they valued that royalty at approximately £15,000, or £1 per infringing Oh Polly garment. The Defendants also accepted that additional damages were payable, but they said that I should order no more than a 20% uplift on the reasonable royalty, which they submitted is approximately £3,000, or 20p per infringing Oh Polly garment. On the other hand, the Claimants submitted that they should receive approximately £275,000 in standard damages, to be “topped up” to approximately £500,000 with additional damages to reflect the flagrancy of the infringement. Thus, the parties were far apart.

Background

- This is the ninth judgment I have given in these proceedings. I do not set out here all the relevant background, which can be found in those earlier judgments. For present purposes, it is sufficient to record as follows.

- After a trial over eight days, on 24 February 2021 I gave judgment in relation to the alleged infringement of UK unregistered design rights (UKUDR) and Community unregistered design rights (CUDR) in 20 selected garments (the Selected Garments) out of a total of 91 garments, which rights the Claimants said were infringed by the Defendants. That judgment can be found at [2021] EWHC 294 (Ch) (the Main Judgment). I found that seven of the Selected Garments infringed both UKUDR and CUDR, and that 13 infringed neither right. I dismissed the passing off claim. I set out below some of my other findings from that judgment relevant to this damages inquiry.

- A form of order hearing took place on 1 April 2021: I gave a short ex tempore judgment (which can be found at [2021] EWHC 836 (Ch)) rejecting the Defendants’ request for declarations of non-infringement. An issue arose after the form of order hearing in relation to the various colourways of some of the seven infringing Selected Garments, and I dealt with that in a judgment which can be found at [2021] EWHC 953 (Ch). I dealt with a further issue relating to costs where a Part 36 offer has been made: that judgment can be found at [2021] EWHC 954 (Ch). Following the Claimants’ election of a damages inquiry in relation to the infringing Selected Garments, I heard a CMC on 24 June 2021. I allowed the Claimants to amend their pleadings for the reasons set out at [2021] EWHC 1848 (Ch). Following these amendments, the Defendants then admitted that a number of the further pleaded garments infringed.

- The Claimants’ Points of Claim in the damages inquiry were served on 20 August 2021. Points of Defence were served on 7 September 2021. There was a hearing before me on 10 September 2021 at which I ordered the Claimants to provide responses to the Defendants’ Request for Further Information dated 24 August 2021: that was duly done on 17 September 2021. Also on 10 September 2021, I refused the Defendants’ request to institute the disclosure pilot and refused most of the Defendants’ requests for specific disclosure. That judgment can be found at [2021] EWHC 2555 (Ch). The Court of Appeal refused the Defendants’ application for permission to appeal.

- On 1 October 2021, I refused the Defendants’ application to vacate the hearing of this damages inquiry, for the reasons set out at [2021] EWHC 2632 (Ch). The Court of Appeal refused the Defendants’ application for permission to appeal.

- On 15 October 2021, I refused the Defendants’ application for specific disclosure in relation to this damages inquiry: see [2021] EWHC 2748 (Ch).

- The inquiry was heard remotely at the request of the parties, over five days. The parties used the CaseLines database so that documents were available electronically to the court and to witnesses. The Claimants were represented by Ms Anna Edwards-Stuart and Mr David Ivison of counsel (instructed by MonoLaw) and the Defendants were represented by Mr Chris Aikens of counsel (instructed by Fieldfisher).

- For ease of reference, each garment in the proceedings has a number. The Claimants’ garments in which they assert UKUDR and CUDR are pre-fixed with the letter C. Where a part design is claimed, an asterix is used. The Defendants’ garments which are alleged to infringe mostly have the corresponding number, prefixed with the letter D (thus, D2 was alleged to infringe design rights in C2 etc). The evidence occasionally used the names of the garment (the Claimants’ garments having girls’ names, and the Defendants’ garments being named with puns or plays on words).

Fact Witnesses

- The Claimants relied on two witnesses of fact.

Joanna Richards

- Ms Joanna Richards is actively involved in running the House of CB business. She primarily gave evidence in relation to her views on a hypothetical negotiation for a reasonable royalty, and the impact of the dispute on the Claimants. Ms Richards had also given evidence at the liability trial: she was cross-examined in that trial, and at this inquiry. Counsel for the Defendants submitted that Ms Richards “was a thoroughly unhelpful witness”, but said further that, “for the most part”, that was not her fault. He submitted that her role at House of CB was limited, and that she did not make key decisions in relation to the business. Even if these submissions were true, I do not consider that this criticism can be made of Ms Richards. I found her to be an honest witness, doing her best to assist the court. The areas where counsel for the Defendants said she lacked knowledge turned out to be largely irrelevant to the issues to be determined in the inquiry.

- Further, on 21 October 2021, the Defendants’ solicitors wrote to the Claimants’ solicitors in the following terms:

“We refer to your second letter dated 12 October 2021, wherein you state that “the issue of which factory makes which garments is utterly irrelevant to any issue still in dispute in these proceedings”.

For the avoidance of doubt our clients reject this proposition. We hereby put you on notice that at trial we will be asking Mr Waters and/or Ms Richards where each of the garments were manufactured and about the relationship between the factory (or factories) and the Claimants. It appears from their evidence that they already know of such matters, but if they do not, we ask that they have that information available to them at trial.”

- The Claimants’ solicitors did not respond to this letter, which was issued one clear day before the inquiry began.

- Under cross-examination, it became apparent that Ms Richards did not know which garments were manufactured at what factory. She had not researched the issue in order to be able to answer the Defendants’ questions. Ms Richards gave evidence that the factories concerned made the decisions on where garments were to be manufactured, and they had all closed more than two years ago.

- Counsel for the Defendants criticised Ms Richards trenchantly for “not check[ing] where the garments were manufactured even though she knew [the Defendants] wished to have that information”. Counsel for the Claimants submitted that I should reject this criticism of Ms Richards: witnesses should be cross-examined on their evidence, she submitted, and Ms Richards had given none in relation to the factories. It is not for witnesses to have to study up on things outside their knowledge in order to be able to answer questions under cross-examination - and they should not be criticised for failing to do so. I accept those submissions.

- Further, counsel for the Claimants submitted that this was the third occasion on which the Defendants had sought to discover which factory made which garment. First, the Defendants had made an application for specific disclosure, which I had already rejected. Second, the Defendants had asked for the information in an RFI, which I had already dismissed. It therefore follows that I accept her submission that no criticism can be made of Ms Richards for not having to hand information outside her knowledge that the Defendants had twice failed to secure by other means, and which was, in any event, of limited, if any, relevance to this inquiry.

David Waters

- Mr David Waters is an accountant at UKTS Limited, and has acted as the UK accountant for the First Claimant since it was incorporated in July 2011, providing accounting and taxation advice. Mr Waters provided calculations as to the Claimants’ lost profits. He was cross-examined. Counsel for the Defendants described Mr Waters as a fair witness who did his best to help the court. I agree with that assessment.

- The Defendants relied on one witness of fact.

Michael Branney

- Dr Michael Branney is the Third Defendant and the managing director of the Oh Polly business. He also gave evidence at the liability trial. Relevantly for present purposes, he gave an affidavit on 26 May 2021 setting out Island Records v Tring information to enable the Claimants to make an election of an account of profits or a damages inquiry. He then made two further witness statements, a third on 22 July 2021 and a fourth on 18 August 2021 providing further details of sales of the infringing Oh Polly garments. His fifth witness statement, his evidence in the damages inquiry, was filed on 4 October 2021.

- As a defendant in the proceedings, he had also signed each of the pleadings filed on behalf of the Defendants.

- Counsel for the Claimants described Dr Branney as “a dishonest litigant and witness”. I have regretfully come to the conclusion that Dr Branney was a dishonest witness, and that his evidence is not to be believed unless corroborated by independent means (such as contemporaneous documents). Given that finding, I need to set out in some detail the relevant background. There are two issues, which are interlinked. One relates to the cessation or otherwise of sales of certain Oh Polly garments. The other relates to the total number of infringing Oh Polly garments sold by the Defendants which Dr Branney set out in his Island Records affidavit.

Cessation of Sales

- The Defendants’ Defence was signed by Dr Branney in January 2019. An Amended Defence was signed by Dr Branney in January 2020. Both included at paragraph 76 a statement that the Defendants “have ceased all sales” of certain garments “and do not intend to recommence sales of such garments”.

- The Amended Defence to the Points of Claim was signed by Dr Branney on 21 October 2021. Paragraph 19G of the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim states:

“However, the latest Infringing Garment in time was first offered for sale on 25 June 2018, which is only 10 days after the claim form and particulars of claim were sent to the registered address of the First to Third Defendants. By the time of the service of the original Defence in January 2019, the Defendants had stopped selling 66 of the 87 garments then complained about.”

- The reference to 66 of 87 garments was a reference to Annex D89 to the original Defence to the Particulars of Claim, referred to at paragraph 76 of the original Defence. Of the 66 garments listed in Annex D89, twelve remain in issue in the litigation: D2, D6, D12, D13, D15, D27, D35, D41, D42, D54, D57 and D61.

- During Dr Branney’s cross-examination, it emerged that sales of many of the 66 garments referred to in the Defence, the Amended Defence and the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim had not in fact ceased, but rather, after a brief hiatus, had commenced again. Of the garments still relevant in these proceedings, only sales of D41 had in fact ceased by January 2019 and not recommenced. Sales of D54 and D57 had ceased some time earlier at the end of their sales cycle.

- Dr Branney stated under cross-examination that he had instructed that the garments be removed from the Oh Polly website but that it later transpired that a person in his team responsible for merchandising had put the garments back on sale without his knowledge. He had discovered on or about 26 September 2021 that sales had not ceased as claimed.

- The result of sales not having ceased as claimed was the second issue to which the Claimants referred, namely, that the total sales of infringing garments set out in Dr Branney’s Island Records affidavit and his third and fourth witness statements did not record the additional sales after January 2019. Those figures (which were supposed to include all sales by the Defendants of the infringing garments) were therefore wrong.

- Dr Branney’s position was that he did not know at the time they were signed that:

(a) the Amended Defence was wrong (because sales had in fact recommenced); and

(b) his Island Records affidavit and third and fourth witness statements were wrong (because they did not include all the Defendants’ sales of infringing garments).

- As set out above, it was Dr Branney’s evidence that he discovered the additional sales on or about 26 September 2021. However, whilst he raised these additional sales with those advising the Defendants (it is to be recalled that Dr Branney is the Third Defendant), no letter was written to the Claimants alerting them to the issue. Rather, Dr Branney, having raised it with his legal team, took two steps. First, he signed the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim on 21 October 2021. This document repeated the statement that sales of the relevant garments had ceased by January 2019, a statement which by this time Dr Branney knew to be false. Second, he signed a fifth witness statement that does not mention the discovery of the extra garment sales after January 2019. In relation to total sales and his Island Records affidavit and third and fourth witness statements it says this (references to the CaseLines database omitted, emphasis added):

“8. I have previously provided evidence on the number of units sold, the gross profits per item and estimated net profits per item for the designs referred to in these proceedings as D2, D4, D12, D13, D35, D61, D85, D87 and D91 in my affidavit of 2 May 2021 [his Island Records affidavit]. I have also provided evidence on the number of units sold and the gross profits per item for the designs referred to in these proceedings as garments D1, D6, D15, D27, D41, D48, D54 and D57 in my third and fourth witness statements, dated 22 July 2021 and 18 August 2021 respectively. The methodologies used at the time to calculate these figures can also be found in the respective affidavit and witness statements.

9. The Defendants were directed by the Order of the Deputy Judge dated 30 July 2021 to use our best endeavours in the time available to ensure that the figures provided for gross profits (with respect to garments D1, D6, D15, D27, D41, D48, D54 and D57) were as accurate as possible. I complied with the 30 July 2021 Order to produce figures to the best accuracy possible in the time provided. However, I am now in a position to state various financial figures with greater certainty.”

- The Defendants rely on the last sentence, which I have italicised, to submit that they brought to the Claimants’ attention the under-reporting in Dr Branney’s Island Records affidavit and third and fourth witness statements.

- Then, at paragraphs 10, 11 and 12 of his fifth witness statement, Dr Branney recorded the steps taken since his third and fourth witness statements to develop a software program to allow for the interrogation of all individual sales records by stock keeping unit (SKU). He defined the software program as “the Program”. He then went on to discuss the different systems used by the Defendants, including Linnworks, Braintree and Magento, and concluded at paragraph 16 (emphasis added):

“The Program has allowed me to record (in the Spreadsheet) the number of units sold, gross profit per item and net profit per item for each of the Infringing Garments with greater confidence than previously possible.”

- The Spreadsheet referred to is a document provided to the Defendants in a Civil Evidence Act notice. I return to that document below.

- Again, the Defendants relied before me on the italicised phrase to support their submission that the discrepancies in garment figures were brought to the Claimants’ attention. In his closing skeleton argument, counsel for the Defendants wrote:

“As soon as [Dr] Branney realised the [Island Records] affidavit contained incorrect figures, he corrected them by serving his 5th statement which referred to the accurate numbers in the spreadsheet provided under cover of CEA Notice.”

- For the reasons set out below, I consider that assertion to be unsupportable.

- Dr Branney was well aware of the need to be honest and frank in his evidence. First, he had given evidence in the liability trial about which I was critical. At paragraphs 60 and 61 of the Main Judgment, I said this:

“However, I consider Dr Branney’s failing here to be maladroit, rather than malevolent. He had not designed the garments in issue - Ms Henderson had. He was working from documents and from Ms Henderson’s explanations. He ought to have been more careful before signing the statement of truth, but I do not consider that this means I should discount his evidence completely. Counsel for the Claimants described Dr Branney’s evidence as that “of a person willing to say whatever needed to be said to achieve his objective.” Having watched him give evidence, I consider that Dr Branney was an active advocate for the Defendants. I have therefore approached his evidence with caution, but I reject counsel for the Claimants’ submission that I should dismiss it altogether.”

- Dr Branney was therefore aware of the importance of honest evidence and the importance of being careful before signing a statement of truth.

- Second, the evidence of the Second Defendant, Ms Henderson, in the liability trial had been criticised (I found that she had lied) and contempt proceedings have been threatened by the Claimants. This became a major issue in the proceedings over the spring for reasons unrelated to the inquiry, with significant correspondence exchanged between the parties. Dr Branney gave instructions on that correspondence. So, again, he was well aware of the possibility of contempt proceedings against untruthful witnesses.

- Third, Dr Branney said that he had been very careful with his evidence. He said he had been “very careful” to check through the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim, since it was a document verified by a statement of truth.

- Unfortunately, I am unable to conclude otherwise than that Dr Branney has fallen short in his honesty to the court. At least by the time he signed his fifth witness statement, he knew that his Island Records affidavit and his third and fourth witness statements were incorrect, and yet he made no attempt to draw this to the attention of the court or the Defendants. I do not for one moment consider that the italicised phrases I have highlighted above were sufficient. They merely say that the figures presented are presented with greater confidence/certainty. They do not even suggest that the previous figures were wrong, and there is no mention at all of the additional sales of infringing garments after it was claimed that sales had ceased. Rather, I understand Dr Branney’s witness statement simply to refer to the Spreadsheet of figures provided to the Claimants via a CEA Notice. He, and the Defendants, then left it to the Claimants to interrogate those figures should they wish. It should be noted that one sheet in the Spreadsheet contains 22,263 lines of data, which would not have been easy to interrogate - it was only through the Claimants’ detailed review of those data that Dr Branney’s earlier inaccurate affidavit and witness statements came to light.

- Counsel for the Claimants also pointed to paragraph 129 of counsel for the Defendants’ opening skeleton argument where he addressed the timing of the infringements for the purposes of additional damages. That document records:

“Further, by the time of the service of the original Defence in January 2019, [the Defendants] had stopped selling 66 of the 87 garments then complained about. That is not the behaviour of a cynical infringer with no regard for the law that should be punished out of all proportion to the scale of the infringements.”

- It is usual for Defendants to review counsels’ skeleton arguments prior to submission to the court, and I can only assume that Dr Branney reviewed this document, which is dated 22 October 2021. Again, by this point, Dr Branney was well aware that, whilst sales stopped in January 2019, for most of the relevant garments they had commenced again. The skeleton argument makes no reference to that fact - indeed, it seeks to make a virtue from the cessation of sales.

- Counsel for the Claimants also submitted that Dr Branney was given an opportunity to explain himself early in his cross-examination, but chose not to do so. She asked him:

“Q: It is right, is it not, Dr Branney, that in the course of this litigation, the Defendants have stated that they have stopped selling some of the garments even though they did not accept that those garments were infringing the Claimants’ rights; correct?

A: That is correct, my Lord.

…

Q: …this is paragraph 19G we have just been looking at. What you are saying here is that it is not entirely fair for the Claimants to say that the Defendants did not cease copying their designs until after these proceedings were launched because in fact, you say, the last infringing garment in time was only launched shortly after the claim was issued; correct?

A: That is correct.

Q: That by the time the original Defence was served you had in fact stopped selling 66 of the 87 infringing garments then in issue; correct?

A: My Lord, that is correct.”

- Even as late as this point, over a month after discovering the error and whilst giving testimony to the court, Dr Branney did not acknowledge that the Defendants’ pleadings in the liability trial and in this inquiry were wrong, and that his affidavit, and now three witness statements (his third, fourth and fifth) were wrong/misleading. I add that shortly after having taken the affirmation, Dr Branney was asked by counsel for the Defendants if there were any corrections he wished to make to his fifth witness statement. He made one. He was then asked: “Subject to those corrections, are the contents of this statement true to the best of your knowledge and belief?” Dr Branney answered “Yes, they are, my Lord”.

- Dr Branney was cross-examined further in relation to the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim. He said he checked it “very carefully”. That document includes the statement “by the time of the service of the original Defence in January 2019, the Defendants had stopped selling 66 of the 87 garments then in issue”. This statement was untrue, and by the time he signed the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim, Dr Branney knew it to be untrue. He did not in cross-examination suggest that he had overlooked this statement - rather, he said “I did not understand that I was signing as if it was a previous date” and “as I stated before, I did not understand that I was signing it as if I had gone back to that date, and I was satisfied that as of 21st October 2021 it was absolutely true”. So on his own testimony, he considered the false statement, and concluded that whilst it had not been true when the Amended Defence was signed in January 2020, sales had ceased by October 2021 and that was enough. But that is not what the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim says - it says that garment sales had stopped in January 2019, which by this time Dr Branney knew not to be true.

- I am prepared to accept Dr Branney’s evidence that he was not aware that the Amended Defence in the liability trial was wrong at the time he signed it under a statement of truth. I am also prepared to accept that Dr Branney was unaware that his Island Records affidavit and his third and fourth witness statements were false at the time they was executed and filed. But by the time Dr Branney (a) signed his fifth witness statement; (b) signed the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim; and (c) gave his oral testimony under affirmation, he was well aware that his affidavit and witness statements were wrong and misleading and that the statement that sales had ceased in January 2019 was wrong, and he chose not to correct those errors in a way which would have been readily perceptible by the Claimants. It is also, regretfully, my finding that those omissions were dishonest.

- The affirmation Dr Branney took on giving his oral testimony included a solemn and sincere affirmation to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. Dr Branney has not done so. He has failed to comply with his affirmation. He was not honest with the court until asked specific questions about the additional sales. He had plenty of opportunities to come clean about the errors, but chose not to do so. I therefore find that his evidence is not to be trusted, and I will accept it only where the Claimants wish to rely on it, or it is corroborated by an independent source. It does not matter that the correct figures were eventually provided, nor that the Claimants have not suggested that they might have elected differently had the Island Records affidavit been correct, and it does no credit to the Defendants’ counsel for suggesting as much in his closing skeleton argument. This was a serious failure to correct two errors once they had been discovered.

- Mistakes sometimes occur. But when a material mistake in a pleading, an affidavit or a witness statement is discovered, the relevant party/ies and/or deponent/s have a duty to bring that mistake to the attention of all other parties, and of the court, as soon as practicable. What should have happened in this case is that, having discovered the additional sales on 26 September 2021, the Defendants should have written through their solicitors to the Claimants, setting out the errors, and then sought to agree a way forward, which may have included amended pleadings (this at least was done, on the final day of the inquiry) and a further witness statement setting out in detail how the error occurred and how it was discovered.

- After the conclusion of the inquiry, and after the above paragraphs of this judgment had been written, I received a sixth witness statement from Dr Branney. That witness statement sought to explain his oral evidence under cross-examination. Dr Branney wrote:

“I have had the opportunity to review the transcripts from my cross-examination (which were provided to me by Fieldfisher) and I wish to clarify what exactly I meant in response to some of the questions that were put to me”.

- Dr Branney had no permission to file such a further witness statement. The Claimants objected to it. I decline to admit it into evidence. Many witnesses who are cross-examined before the court would welcome an opportunity, after reflection, to explain in writing comments they have made under cross-examination, without fear that they will be further cross-examined on that written explanation. It was inappropriate for Dr Branney to seek to do so. I should add that, even if I had taken his sixth witness statement into consideration, it would not have made a difference to the conclusions I have reached above.

- Counsel for the Defendants submitted that even if I were to find that Dr Branney was a dishonest witness, it does not matter, because the Defendants relied on little of his evidence. I do not accept that the Defendants have relied on little of Dr Branney’s evidence, and where they have, I have disregarded it as I have set out below.

The Defendants’ Legal Advisors

- Because of the seriousness of the issues surrounding the pleadings and Dr Branney’s affidavit and witness statements, at the close of the evidence I invited the Defendants’ legal advisors to submit a witness statement to “explain what happened in a full and frank way”. A twelfth witness statement of Mr James Seadon of the Defendants’ solicitors was filed and served prior to closing speeches, but the witness statement only dealt with the under-reported numbers issue, not the cessation of sales issue. Counsel for the Defendants made submissions about the conduct of the Defendants’ advisors in his closing speech, but, during the Claimants’ counsel’s closing speech later in the day, counsel for the Defendants interrupted to say that he may have misspoken earlier in the day, and that nothing in his closing speech was intended to add to the evidence which had been provided in Mr Seadon’s twelfth witness statement. With my permission, Mr Seadon then filed a thirteenth witness statement to deal with the cessation of sales issue. That witness statement arrived on time and after the inquiry had concluded.

- In relation to Dr Branney’s Island Records affidavit, Mr Seadon gave evidence that Dr Branney's fifth witness statement was intended to be the correction to the sales figures given earlier.

- In relation to the recommencement of sales issue, Mr Seadon wrote:

“With the benefit of hindsight, my firm should have appreciated that the later sales meant that paragraph 76 of the Original Defence was wrong, we should have brought this to the attention of the Claimants promptly and we should not have included the last sentence of paragraph 19G of the Amended Defence to the Points of Claim.”

- Further, Mr Seadon wrote:

“It would also have been appropriate to flag prominently in correspondence and/or in Dr Branney’s witness evidence that it had become apparent that the sales information previously given, in the belief it was true, was incorrect. Although the correct figures were indeed provided before trial, I accept that a prominent correction would have been appropriate together with a clear explanation for how the wrong figures were provided in the Affidavit (albeit innocently)”.

- I accept Mr Seadon’s explanation, although it strains credulity that any legal professional (solicitor or barrister) can have considered that the steps that were taken to correct Dr Branney’s false Island Records affidavit were sufficient in this case. This has been hard-fought litigation, where very few stones have been left unturned. I am told that in the period between the discovery of the additional sales (26 September 2021) and the start of the inquiry (25 October 2021), almost exactly one month, Mr Seadon’s firm sent 50 letters to the Claimants’ solicitors. I have not counted them myself, but in the context of this litigation, that seems plausible. In any of those, the undercounted garments issue could have been raised - and, in my judgment, should have been raised in terms. The steps taken were wholly inadequate for the reasons I have set out above, and which Mr Seadon now acknowledges.

- Mr Seadon’s explanation does not excuse Dr Branney, who had an obligation to tell the truth, regardless of the (in my judgment, incorrect) advice he was given. Dr Branney ought to have spoken up earlier, and at the very latest when he was questioned under his affirmation.

Expert Witnesses

Matthew Geale

- The Claimants relied on one expert witness, Mr Matthew Geale, a partner at Armstrong Watson LLP. Mr Geale is a forensic accountant with many years of experience. He has previously given expert evidence before this court in other matters and also in other tribunals. His report ran to 103 pages. Mr Geale reviewed the evidence as he understood it, and provided his opinions as to losses and royalties. He also provided his views on the hypothetical negotiation of a reasonable royalty. He was cross-examined.

- Counsel for the Defendants described Mr Geale as having given “exemplary expert evidence” except in one respect - he criticised Mr Geale’s evidence on licences with royalty rates based on a percentage of the licensor’s selling price, for which he did not provide any examples. I accept that criticism. I make some further comments below on the expert evidence in this case more generally.

David Dearman

- The Defendants’ relied on the expert evidence of Mr David Dearman, a Senior Managing Director at Ankura Consulting (Europe) Limited. Mr Dearman is also an experienced forensic accountant. He provided two reports, the first of which ran to 397 pages, and the second of which totalled 21 pages. He gave evidence about the Claimants’ claim for damages based on lost profits, and gave his views on a reasonable royalty. In his second witness statement, he responded to Mr Geale’s evidence on the likely reasonable royalty and the differences in price between the parties’ respective garments. He was cross-examined.

- The Claimants did not criticise Mr Dearman’s honesty (in my view, quite rightly), but did submit that he did not perform properly the role of independent assistant to the court. In particular, the Claimants’ counsel submitted that he had “clearly gone out of his way to develop support for the Defendants’ case”, including by adopting Dr Branney’s evidence without question (despite having described it as “extreme”) whilst ignoring the Claimants’ position, presenting conclusions on the parties’ sales data that simply could not be supported, and suggesting “obviously un-comparable licences” were comparables for the purposes of determining a reasonable royalty.

- I have no doubt at all that Mr Dearman was presenting his evidence honestly. However, he based his opinions heavily on Dr Branney’s evidence, which I have held cannot be relied on unless independently verified. He accepted under cross-examination that he had based his evidence on Dr Branney’s evidence, and had not relied on Ms Richards’ evidence. He also, in my judgment, had a tendency to argue the Defendants’ case, giving answers under cross-examination that set out that case, rather than responding to the questions put to him.

- He was also asked to examine matters beyond his expertise, and issues that were ultimate questions for me. For example, at paragraph 7.1.2 of his first expert report, Mr Dearman said:

“In this section of my report I have been asked to give my opinion on what the Claimants and the Defendants would have agreed as a reasonable royalty on sales of Infringing Garments in circumstances where the Defendants had sought a licence from the Claimants to use the Infringed Designs prior to the acts of infringement and where the parties were willing licensors and licensees respectively”.

- With respect to Mr Dearman, that was simply not within his expertise as a forensic accountant, and was, in any event, the ultimate question for me on which he should not have been asked to opine.

- For these reasons, I have treated his evidence with some care.

- I reiterate Jacob LJ’s comments in Rockwater Ltd v Technip France SA and Anor [2004] EWCA Civ 381 at paragraph 12. That was a patent case, but his comments about the role of expert evidence are apposite in this case:

“I must explain why I think the attempt to approximate real people to the notional [person] is not helpful. It is to do with the function of expert witnesses in patent actions. Their primary function is to educate the court in the technology - they come as teachers, as makers of the mantle for the court to don. For that purpose it does not matter whether they do not approximate to the skilled [addressee]. What matters is how good they are at explaining things.”

- It is not the role of expert evidence in damages inquiries to proffer answers to the questions that are those for the court. For example, and as both counsel agreed, it is for the court to assess the hypothetical negotiation between two willing parties in order to try to reach a reasonable royalty. Here, experts can set out what they have observed in other licences, but they are of limited if any help to the court in suggesting what these particular parties might have agreed. They can model various outcomes - but if those models are based on contested facts which the court does not find to be accurate, then their models are of limited use. Similarly, expert forensic accountants can provide only limited (if any) evidence on whether an infringing garment purchased from the Defendants was a sale lost by the Claimants. Therefore, in my judgment, whilst both experts tried to do their best with the instructions they were given, and answered honestly the questions put to them, both were asked to go beyond their proper tasks and to stray into matters that are for the court to decide. Their written evidence was exceedingly long for a case of this type, and ought to have been significantly shorter, dealing only with matters within their competence.

Additional Factual Background

- For ease, I set out below factual findings from the Main Judgment which are relevant to the issues in the inquiry:

(a) “The First Claimant, through its then solicitors, first wrote to the First and Third Defendants on 19 April 2016, alleging passing off, and that eight Oh Polly garments (sold in various colourways) infringed its UKUDR and CUDR.” (Main Judgment, paragraph 4).

(b) “It was common ground that Ms Henderson cannot draw. She also cannot use any of the available computer assisted design programs. Her evidence was that she designed by looking at trends from images she had collected in her Dropbox, designed the details of each garment in her head, and then looked for images of existing garments which she could use to show the factory what it was she wanted made. There are no documents which (and no other witnesses who) back up this aspect of her account of her design process.” (Main Judgment, paragraph 53).

(c) “I consider [Ms Henderson’s] version of her design process to be a fabrication, concocted to get around the very real difficulty that Ms Henderson took images of the Claimants’ garments (and third party garments) and sent them to the factory to be made up. I therefore, regrettably, accept counsel for the Claimants’ submission that Ms Henderson’s evidence cannot be trusted. In my judgment, she set out to deceive the Claimants and the Court in relation to her overall design process, and the design of the particular garments before me. In her oral testimony, she gave whatever answer she felt best at that moment to assist her case. That criticism also extends to her written testimony.” (Main Judgment paragraphs 54 and 55).

(d) “In 2015, Ms Henderson and Dr Branney decided to set up their own business. They adopted the name Oh Polly for that business, and launched a website at www.ohpolly.com in August 2015. The Fourth Defendant took over the business in June 2017. Ms Henderson’s evidence was that at the start of the Oh Polly business, she designed all the garments sold by the business, designing 40 to 50 garments per month. Ms Johnston joined Oh Polly as a designer in 2017. Oh Polly garments are made in factories in Bangladesh and China.” (Main Judgment, paragraph 76).

(e) “By way of example only, take D2. Ms Henderson found a picture of C2 on social media and took a screen shot. That screen shot was uploaded to Trello [the Defendants’ garment design and manufacturing records system] for the Defendants’ manufacturer to work from. There were no other drawings, patterns or plans. There was a third party garment also shown on the Trello records, but, as I have said, copying more than one design is still copying.” (Main Judgment, paragraph 115).

(f) “…it is clear that some aspects of a garment will strike the informed user as more important. In this case, all the dresses were primarily photographed from the front: whilst photographs of the back aspect were included on both sides’ websites, they were not the primary image. From that, I take it that the front of each garment will be of primary importance to the informed user in most cases. Differences on the back of the garment will still be noticed, but they will not be given the importance of the front of the garment.” (Main Judgment, paragraph 131).

(g) “I also need to say something about fabrics. The Oh Polly business is entirely online. Whilst the House of CB business does have some bricks and mortar stores, the bulk of its business is also online. That means that the majority of purchasing decisions are being made based on the images of the garments shown on the websites. Of course, the evidence also demonstrated that something like 30% of online sales are returned. Consumers will return a garment they have purchased on-line if, for example, they do not like the texture or fit. But 70% of sales were not returned, from which I conclude that the experience of the garment on receipt matched the expectation from viewing the garment on the website. It seems to me that what matters is what the dress looks like when worn. Thus, where the images with which I have been provided (which were taken from the parties’ websites) show very similar looking dresses, it will matter less to the informed user that, on a hanger, the dresses do not look as similar.” (Main Judgment, paragraph 132).

(h) “Of Ms Henderson’s 17 “designs”, I have found that 7 of the 9 in which the Claimants’ designs were “referenced” were, at law, copied. In every case in which the Claimants’ designs were not referenced, third party designs were. There is no reliable evidence before me that Ms Henderson ever created mood boards, digital or otherwise. What she did was identify third party designs that she liked, and send images of them to the factory to be copied.” (Main Judgment, paragraph 390).

(i) “Both the Claimants and the Defendants operate an internet business selling celebrity-inspired fashion. Both use social media heavily. Both generate publicity from third parties wearing their garments (including influencers and celebrities). Neither does much or any traditional hard copy advertising (magazines, bill-boards etc), although others in the industry (such as BooHoo) do. Both the Claimants and the Defendants focus on figure-hugging bandage and bodycon dresses designed for a curvy figure. Both sell dresses for younger women to wear on a night out. These similarities were not contested: the parties are competitors, operating very similar businesses.” (Main Judgment, paragraph 426).

(j) “I accept Counsel for the Claimants’ submission that the designs of the parties’ garments is an important aspect of the distinctiveness of their brands - it is something each relies on for the “lifestyle” (or brand) to which I have referred above.” (Main Judgment, paragraph 428).

(k) “The Claimants also relied on public recognition of the frequent similarity of Oh Polly designs to House of CB designs, including the following social media posts:

“Girl I got a dress from Oh Polly for $63 that was $180 on House of CB…”

“Seeing as OhPolly copy all of HouseOfCb designs, are their clothes good quality?”

“Wish @ohpoly would put as much effort into makin their website work properly as it didn’t take people’s money & cancel orders, as it did into copying designs from House of CB”

“Oh Polly … just COMPLETELY copy House of CB designs…”

“Oh Polly just rip off House of CB designs…”

“Oh Polly fully copying House of CB designs”

Whether or not the above examples indicate confusion, they do indicate the consumers’ views that the garments were similar, and that the House of CB garments were perceived as being first in time.” (Main Judgment, paragraphs 431 and 432).

(l) “…as counsel for the Claimants submitted, and I accept, the Defendants did not seek to argue that the garments before me were not representative of the two businesses overall.” (Main Judgment, paragraph 433).

(m) “In relation to the 20 garments in issue before me, I have found that 7 of the Defendants’ garments infringe the Claimants’ unregistered design rights. The corollary of that is that the other 13 garments do not infringe. Be that as it may, there is clear evidence of a public perception, at least among some social media posts, that Oh Polly has copied House of CB’s garments, in the context where the parties are agreed that the two businesses operate in the same market, in similar ways.” (Main Judgment, paragraph 434).

(n) “There was evidence before me of Oh Polly garments being wrongly returned to House of CB, and vice versa. … In other cases, it was clear that the purchaser had purchased both House of CB and Oh Polly garments at the same time, and got in a muddle.” (Main Judgment, paragraph 483).

(o) “There was in the evidence and in some of the earlier submissions and questioning a suggestion that House of CB garments were targeted at a different market to Oh Polly garments. In his written closing submissions, counsel for the Defendant acknowledged that Oh Polly considers House of CB to be its biggest competitor, and that both brands sell garments to “fashion-conscious young women in the UK who are looking to buy sexy clothing online and, in particular, dresses for a night out”. He also acknowledged that their customer bases overlap. This position is consistent with the evidence that consumers buy from both brands.” (Main Judgment, paragraphs 486 and 487).

(p) “Therefore, in my judgment, the only conclusion open to me is that Ms Henderson set out to emulate House of CB, and directed Oh Polly staff to hire the same models, rent the same locations, adopt similar hair and makeup, adopt similar flatlays, follow the House of CB packaging from bright pink to softer pink, adopt a similar website etc. She herself copied some House of CB garments, as I have found above, albeit that she also copied garments of other designers as well.” (Main Judgment, paragraph 491).

(q) “I have found that the Defendants have infringed the Claimants’ UKUDR and CUDR in relation to 7 garments. Whilst Ms Henderson, the named designer of the relevant garments, has denied copying, I have held her not to be an honest witness, and I have discounted her evidence unless it is corroborated by other evidence. What is clear from the written record is that for the Defendants’ garments D2, D4, D12, D13, D35, D61 and D91, Ms Henderson took an image of the Claimants’ garments, and sent it to the factory to be reproduced. In the circumstances of this case, that is sufficient to warrant an award of additional damages in relation to those designs. It was at least an attitude of “couldn’t care less” about the rights of others: a designer, as Ms Henderson claimed to be, of her years of experience ought to have known (if she did not in fact know) that such activity was not lawful. In reaching that conclusion, I do not need to rely on the Claimants’ submissions in relation to the alleged scale of infringement, the alleged concerted efforts to emulate the House of CB business or the allegedly misleading positions taken by the Defendants in this litigation. I do, however, take into account the Claimants’ final submission on this point, which was that the Defendants have been on notice of the Claimants’ concerns since 2016. Rather than choose to stop “referencing” the Claimants’ designs, the Defendants continued, even after these proceedings were launched.” (Main Judgment, paragraphs 509 and 510).

Standard Damages

- I turn first to standard damages.

The Law on Standard Damages

- The parties agreed on the law to be applied in the assessment of standard damages. Kitchin J (as he then was) set out the principles in Ultraframe (UK) Limited v Eurocell Building Plastics Limited and Anor [2006] EWHC 1344 (Pat) at [47] (whilst that case involved patent infringement, the parties agreed that the judgment applies equally here):

“(i) Damages are compensatory. The general rule is that the measure of damages is to be, as far as possible, that sum of money that will put the claimant in the same position as he would have been in if he had not sustained the wrong.

(ii) The claimant can recover loss which was (i) foreseeable; (ii) caused by the wrong; and (iii) not excluded from recovery by public or social policy. It is not enough that the loss would not have occurred but for the tort. The tort must be, as a matter of common sense, a cause of the loss.

(iii) The burden of proof rests on the claimant. Damages are to be assessed liberally. But the object is to compensate the claimant and not to punish the defendant.

(iv) It is irrelevant to a claim of loss of profit that the defendant could have competed lawfully.

(v) Where a claimant has exploited his patent by manufacture and sale he can claim (a) lost profit on sales by the defendant that he would have made otherwise; (b) lost profit on his own sales to the extent that he was forced by the infringement to reduce his own price; and (c) a reasonable royalty on sales by the defendant which he would not have made.

(vi) As to lost sales, the court should form a general view as to what proportion of the defendant’s sales the claimant would have made.

(vii) The assessment of damages for lost profits should take into account the fact that the lost sales are of “extra production” and that only certain specific extra costs (marginal costs) have been incurred in making the additional sales. Nevertheless, in practice costs go up and so it may be appropriate to temper the approach somewhat in making the assessment.

(viii) The reasonable royalty is to be assessed as the royalty that a willing licensor and a willing licensee would have agreed. Where there are truly comparable licences in the relevant field these are the most useful guidance for the court as to the reasonable royalty. Another approach is the profits available approach. This involves an assessment of the profits that would be available to the licensee, absent a licence, and apportioning them between the licensor and the licensee.

(ix) Where damages are difficult to assess with precision, the court should make the best estimate it can, having regard to all the circumstances of the case and dealing with the matter broadly, with common sense and fairness.”

- HHJ Hacon added to those principles in SDL Hair Limited v Next Row Limited [2014] EWHC 2084 (IPEC) at [31]:

“(6) An inquiry will generally require the court to make an assessment of what would have happened had the tort not been committed and to compare that with what actually happened. It may also require the court to make a comparison between, on the one hand, future events that would have been expected to occur had the tort not been committed and, on the other hand, events that are expected to occur, the tort having been committed. Not much in the way of accuracy is to be expected bearing in mind all the uncertainties of quantification. See Gerber v Lectra at first instance [1995] RPC 383, per Jacob J, at 395-396.

(7) Where the claimant has to prove a causal link between an act done by the defendant and the loss sustained by the claimant, the court must determine such causation on the balance of probabilities. If on balance the act caused the loss, the claimant is entitled to be compensated in full for the loss. It is irrelevant whether the court thinks that the balance only just tips in favour of the claimant or that the causation claimed is overwhelmingly likely, see Allied Maples Group v Simmons & Simmons [1995] WLR 1602, at 1609-1610.

(8) Where quantification of the claimant’s loss depends on future uncertain events, such questions are decided not on the balance of probability but on the court’s assessment, often expressed in percentage terms, of the loss eventuating. This may depend in part on the hypothetical acts of a third party, see Allied Maples at 1610.

(9) Where the claim for past loss depends on the hypothetical act of a third party, i.e. the claimant’s case is that if the tort had not been committed the third party would have acted to the benefit of the claimant (or would have prevented a loss) in some way, the claimant need only show that he had a substantial chance, rather than a speculative one, of enjoying the benefit conferred by the third party. Once past this hurdle, the likelihood that the benefit or opportunity would have occurred is relevant only to the quantification of damages. See Allied Maples at 1611-1614.”

- In relation to lost profit damages, the parties were in agreement that I should, on the basis of Allied Maples, apply a two-stage approach:

(a) First, on the balance of probabilities, have the Claimants suffered some loss under the head claimed? If the answer is “no”, then the inquiry stops there. If the answer is “yes”, then the inquiry moves to the next stage.

(b) Second, on the basis of the available evidence, how much loss has been sustained?

- Counsel for the Claimants submitted that for the purposes of the second stage, it does not matter whether at the previous stage the court was, for example, 51% sure or 100% sure that some loss had been sustained under the head claimed: the court is simply concerned with finding a figure to compensate for the head of loss which it has already found to have been sustained. Counsel for the Defendants did not object to that approach, and I accept it. I was further referred to the judgment of the Court of Appeal in Parabola Investments Limited and Anor v Browallia Cal Limited [2010] EWCA Civ 486 at [23]:

“The claimant has first to establish an actionable head of loss. This may in some circumstances consist of the loss of a chance, for example, Chaplin v Hicks [1911] 2 KB 786 and Allied Maples Group Limited v Simmons & Simmons [1995] 1 WLR 1602, but we are not concerned with that situation in the present case, because the judge found that, but for Mr Bomford’s fraud, on a balance of probability Tangent would have traded profitably at stage 1, and would have traded more profitably with a larger fund at stage 2. The next task is to quantify the loss. Where that involves a hypothetical exercise, the court does not apply the same balance of probability approach as it would to the proof of past facts. Rather, it estimates the loss by making the best attempt it can to evaluate the chances, great or small (unless those chances amount to no more than remote speculation), taking all significant factors into account. (See Davis v Taylor [1974] AC 207, 212 (Lord Reid) and Gregg v Scott [2005] 2 AC 176, para 17 (Lord Nicholls) and paras 67-69 (Lord Hoffmann)).”

- Counsel for the Claimants submitted that the second stage of this exercise may be artificial and difficult, because the court is called upon to make findings about what would have happened in a hypothetical world in which the defendants had not infringed. That does not mean, she said, that the court can throw up its hands and declare the exercise too difficult. Rather, she said, the court’s task is to do the best job it can with the material the parties have put before it. I accept that submission. She referred me to the speech of Lord Wilberforce in General Tire and Rubber Company v Firestone Tyre and Rubber Company [1975] WLR 819 at page 826:

“The ultimate process is one of judicial estimation of the available indications.”

- Counsel for the Claimants also referred me to the judgment of Jacob J (as he then was) in Gerber Garment Technology Inc v Lectra Systems ltd and Anor [1995] RPC 383:

“In short one cannot expect much in the way of accuracy when the court is asked to re-write history.”

- HHJ Hacon dealt with the applicable principles for loss of royalties in Henderson v All Around the World Recordings Limited [2014] EWHC 3087 (IPEC) at paragraph 18 (again, the parties agreed that these principles, albeit set out in the context of performers’ rights, are also applicable to the unregistered design rights in this case):

“18. In Force India Formula One Team Limited v 1 Malaysia Racing Team Sdn Bhd [2012] EWHC 616 (Ch); [2012] RPC 29 Arnold J considered Wrotham Park damages, i.e. of the type awarded in Wrotham Park Estate Co Ltd v Parkside Homes Ltd [1974] 1 WLR 798. In Force India damages for breach of a restrictive covenant in a contract were taken to be the amount of money which could reasonably have been demanded by the claimant for a relaxation of the covenant. Arnold J identified the following principles (at [386]):

“(i) The overriding principle is that the damages are compensatory: see Attorney-General v Blake at 298 (Lord Hobhouse of Woodborough, dissenting but not on this point), Hendrix v PPX at [26] (Mance LJ, as he then was) and WWF v World Wrestling at [56] (Chadwick LJ).

(ii) The primary basis for the assessment is to consider what sum would have [been] arrived at in negotiations between the parties, had each been making reasonable use of their respective bargaining positions, bearing in mind the information available to the parties and the commercial context at the time that notional negotiation should have taken place: see PPX v Hendrix at [45], WWF v World Wrestling at [55], Lunn v Liverpool at [25] and Pell v Bow at [48]–[49], [51] (Lord Walker of Gestingthorpe).

(iii) The fact that one or both parties would not in practice have agreed to make a deal is irrelevant: see Pell v Bow at [49].

(iv) As a general rule, the assessment is to be made as at the date of the breach: see Lunn Poly at [29] and Pell v Bow at [50].

(v) Where there has been nothing like an actual negotiation between the parties, it is reasonable for the court to look at the eventual outcome and to consider whether or not that is a useful guide to what the parties would have thought at the time of their hypothetical bargain: see Pell v Bow at [51].

(vi) The court can take into account other relevant factors, and in particular delay on the part of the claimant in asserting its rights: see Pell v Bow at [54]”.

The Court of Appeal in Force India ([2013] EWCA Civ 780; [2013] RPC 36) did not dissent from Arnold J’s summary of the law (at [97]).

19. Wrotham Park damages, though they are for breach of contract, are in all relevant respects the same as those I have to consider under this head, so the foregoing principles set out by Arnold J apply. In the inquiry as to damages for infringement of trade marks in 32Red OKC v WHG (International) Limited & ors [2013] EWHC 815 (Ch), Newey J’s assessment was by consent also on the basis of willing licensor and willing licensee. Newey J endorsed the principles identified by Arnold J and expanded on them as follows:

"(vii) There are limits to the extent to which the court will have regard to the parties’ actual attributes when assessing user principle damages. In particular

(a) the parties’ financial circumstances are not material;

(b) character traits, such as whether one or other party is easygoing or aggressive, are to be disregarded [29]-[31].

(viii) In contrast, the court must have regard to the circumstances in which the parties were placed at the time of the hypothetical negotiation. The task of the court is to establish the value of the wrongful use to the defendant, not a hypothetical person. The hypothetical negotiation is between the actual parties, assumed to bargain with their respective strengths and weaknesses [32]-[33].

(ix) If the defendant, at the time of the hypothetical negotiation, would have had available a non-infringing course of action, this is a matter which the parties can be expected to have taken into account [34]-[42].

(x) Such an alternative need not have had all the advantages or other attributes of the infringing course of action for it to be relevant to the hypothetical negotiation [42].

(xi) The hypothetical licence relates solely to the right infringed [47]-[50].

(xii) The hypothetical licence is for the period of the defendant’s infringement [51]-[52].

(xiii) Matters such as whether the hypothetical licence is exclusive or whether it would contain quality control provisions will depend on the facts and must accord with the realities of the circumstances under which the parties were hypothetically negotiating [56]-[58].”

- As mentioned above, I was also referred to the judgment of Jacob J in Gerber v Lectra from which the principles in Ultraframe were derived. Again, Gerber was a damages inquiry for patent infringement, but the parties agreed it is applicable here. The judge held at paragraphs 413 to 420:

“In relation to fixing the royalty for a licence of right, Dillon LJ said in Allen & Hanburys Ltd’s (Salbutamol) Patent [1987] RPC 327 that the position of the patentee as manufacturer is not to be taken into account (at 378-379). Fox LJ agreed, though Woolf LJ dissented (at 384-386). Moreover Dillon LJ (with both of the other members of the court) was of the view that the royalty need not be such that the licensee would find it commercially worthwhile to sell.

Mr. Floyd submitted that there may be a conflict here between the reasonable royalty for damages and the royalty which might be fixed by the Comptroller. In particular he suggested that when I came to fix the appropriate rate of royalty I should take into account the position of Gerber as manufacturer.

I do not agree. One is here considering a notional bargain about sales the patentee would not make. Whether one considers that in advance of the infringement or after seems to me to make no difference (Mr Floyd suggested it did). I do not see why the patentee could reasonably insist on his lost profits on transactions he would not have made.

…

7. Royalties on Sales Gerber would not have made

I have held that there would have been 11 of these. To these should, it is agreed, be added the 2 Irish sales. Gerber are entitled to a reasonable royalty. This is really a court-imposed notional bargain. I have held that Gerber’s lost profits would be irrelevant - because the negotiation does not cover lost Gerber sales.

…

As to how the “available profits” were to be split, absent the extra profits from spares etc. it was agreed that the split would be 25% to the patentee. Gerber’s expert suggested that this ought to be doubled because the licensee would be competing, leading to a royalty of 50% of the licensee’s sales revenue. As I have indicated I think this wrong - we are here talking about the non-competing sales.”

- I was also referred to McGregor on Damages (21st Edition) at paragraph 14-046:

“The circumstances of the parties and any actual negotiations

As explained above, the hypothetical negotiation is conducted as an objective exercise between persons who are assumed to act reasonably. Hence, the court must ignore personal characteristics such as the easygoing nature of one party or the aggressive approach of another. Courts also treat as a personal characteristic the financial position of the parties. Hence, an impoverished defendant cannot avoid an assessment of a significant licence fee on the basis that they would not be able to pay a licence fee that is more than that for which a claimant could reasonably have demanded simply because the defendant might have the resources and willingness to pay a larger amount.”

- Further guidance on the hypothetical negotiation is to be found in the speech of Lord Wilberforce in General Tire at page 833:

“My Lords, this passage is, in my opinion, unsupportable in law or in fact. In law it rests upon the hypothesis that what has to be considered, in measuring the loss a patentee sustains through an infringement, is some bargain struck between some abstract licensor and some abstract licensee uncontaminated by the qualities of the actual actors. But that is not so. The ‘willing licensor’ and ‘willing licensee’ to which reference is often made (and I do not object to it so long as we do not import analogies from other fields) is always the actual licensor and the actual licensee who, one assumes, are willing to negotiate with the other - they bargain as they are, with their strengths and weaknesses, in the market as it exists.”

- As Warren J noted in Field Common Limited v Elmbridge BC [2008] EWHC 2079 (Ch) at [78] (emphasis in original):

“However, in the cases where the hypothetical negotiation has been adopted, it has been the case that the value of the benefit to the particular defendant can be seen to be the value of the benefit which any person in the position of the defendant would receive. That may not be so in all cases. Where it is not so, a hypothetical negotiation may not give the right answer. Or, if that approach nonetheless has to be applied, it will be important to recognise that it is designed to establish the value of the wrongful use to the defendant and not some objective figure as between hypothetical persons negotiating for a hypothetical license: after all, even if damages are to be seen as compensation for loss of an opportunity to negotiate, that negotiation would be one between the actual parties, albeit that they are to be treated as parties willing to deal with each other with a view to reaching a reasonable result.”

- Counsel for the Claimants submitted that as I consider the hypothetical negotiation in this case, both sides’ needs, means, and concerns must be taken into account. If, for example, the licensor will itself suffer as a result of granting a licence, this, she said, will be material, citing Mr Anthony Mann QC (sitting as a Deputy High Court Judge) (as he then was) in AMEC Developments Limited v Jury’s Hotel Management (UK) Ltd [2001] 82 P & CR 22 at [12]:

“It is also common ground that the way of ascertaining what that sum is, is to consider the sum that would have been arrived at in negotiations between the parties had each been making reasonable use of their respective bargaining positions without holding out for unreasonable amounts. This requires, in turn, that the parties have regard to the cost or detriment to the claimant and the benefits to the defendant of the latter’s being allowed to build over the building line.”

- Further, she submitted that the hypothetical negotiation is a prospective one: it takes place before any acts which would otherwise constitute infringement are committed. Save for the actual number of sales made by a defendant, events which, in fact, took place after the hypothetical negotiation would have happened are strictly irrelevant - and so the infringer’s actual profit is not a factor which the parties would have taken (or been able to take) into account. After all, the exercise is not an ex post facto account of profits which have already accrued to a defendant - necessarily, by the time a damages inquiry takes place the claimant has elected not (or is not entitled) to pursue that kind of relief. She referred me to the judgment of Neuberger LJ (as he then was) in Lunn Poly Limited and Anor v Liverpool & Lancashire Properties Limited and Anor [2006] EWCA Civ 430, commenting on the judgment of Mr Mann QC I have referred to immediately above:

“28. Accordingly, although I see the force of what Mr Mann said in paragraph 13 of his judgment, it should not in my opinion be treated as being generally applicable to events after the date of breach where the court decides to award damages in lieu on a negotiating basis as at the date of breach. After all, once the court has decided on a particular valuation date for assessing negotiating damages, consistency, fairness, and principle can be said to suggest that a judge should be careful before agreeing that a factor which existed at that date should be ignored, or that a factor which occurred after that date should be taken into account, as affecting the negotiating stance of the parties when deciding the figure at which they would arrive.

29. In my view, the proper analysis is as follows. Given that negotiating damages under the Act are meant to be compensatory, and are normally to be assessed or valued at the date of breach, principle and consistency indicate that post-valuation events are normally irrelevant. However, given the quasi-equitable nature of such damages, the judge may, where there are good reasons, direct a departure from the norm, either by selecting a different valuation date or by directing that a specific post-valuation-date event be taken into account.”

- In Pell Frischmann Engineering Limited v Bow Valley Iran Limited and Ors [2009] UKPC 45, the Privy Council approved Neuberger LJ’s analysis in Lunn Poly and noted:

“51. In a case (such as

Wrotham Park

itself) where there has been nothing like an actual negotiation between the parties it is no doubt reasonable for the court to look at the eventual outcome and to consider whether or not that is a useful guide to what the parties would have thought at the time of their hypothetical bargain.”

- Citing both Lunn Poly and Pell McGregor on Damages concludes at paragraph 14 - 55:

“This is the reason why the actual profit made from an infringement or the actual use made from the tort are irrelevant.”

- In reaching my conclusions on standard damages, I have kept all of the above front of mind. I have particularly kept in mind that damages are to be assessed liberally, with the object to compensate the claimant and not to punish the defendant. As to lost sales, the court should form a general view as to what proportion of the defendant’s sales the claimant would have made. Where damages are difficult to assess with precision, the court should make the best estimate it can, having regard to all the circumstances of the case and dealing with the matter broadly, with common sense and fairness. Not much in the way of accuracy is to be expected bearing in mind all the uncertainties of quantification.

Lost Profit Damages

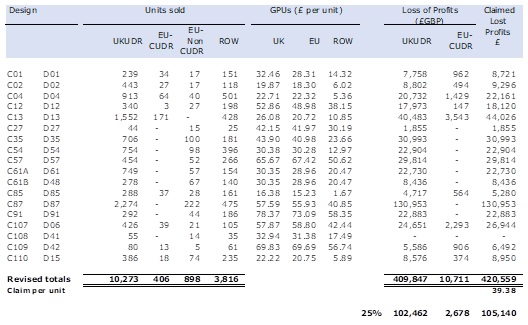

- The Claimants’ case on lost profit damages was as follows:

“Lost profit = number of lost sales of the Infringing Garment (Lost Sales) x total per-unit profit for the Claimants’ garments incorporating the respective Infringed Design (Per Unit Profit)

Lost Sales = total number of Defendants’ sales of Infringing Garment x P

where 0 < P ≤ 1, representing the probability that a sale in fact made by the Defendants of an Infringing Garment was to a customer who would have purchased the respective Claimant’s Garment had the Infringing Garment not been available."

- The Defendants agreed with this approach, but disputed the value of P. It was also agreed between the parties that it is not possible to state the value of P definitively without interviewing the customers for the 15,393 infringing garments, or at least undertaking a statistically significant survey of them, which would have been disproportionate.

- The Claimants’ pleadings valued P at 1 (that is, every infringing sale made by the Defendants was a sale lost by the Claimants). By their closing submissions, the Claimants submitted that P = 0.25 (that is, for every hundred infringing sales made by the Defendants, 25 were sales lost by the Claimants). Put another way, absent the Defendants’ infringement, the Claimants would have made 25% of the sales that the Defendants did in fact make of the infringing garments. The Defendants maintained throughout that P = 0, that is, that none of the 15,393 infringing sales was a sale lost by the Claimants.

- As set out above, I must follow a two stage approach, first determining if any of the Defendants’ infringing sales was a sale lost to the Claimants. If I find that even a single sale was lost, I must then move on to the second stage. However, if I find that no infringing sales were lost, then P = 0, and no lost profits damages will be awarded.

Does P = 0?

- The parties agreed that there was no direct evidence from consumers on the value of P - no-one was brought forward to say “I bought the Defendants’ infringing garment instead of the Claimants’ garment from which the Defendants’ garment was copied”. This was unsurprising. It was also not a topic on which the experts could give meaningful evidence (consumer behaviour being outside their field of expertise). The Claimants relied on findings from the Main Judgment to support their position that P > 0, namely:

(a) House of CB and Oh Polly are direct competitors: indeed, at the time of the infringement, Dr Branney considered House of CB to be Oh Polly’s most significant competitor. The two businesses were very similar, producing similar types of garments (bodycon and bandage garments) for an overlapping customer base;

(b) The infringing garments were articles of clothing - “sexy” garments to be worn on a night out. The driving factor behind a purchase was the look of the garment - whilst approximately a third of on-line purchased garments were returned (to both businesses), this does not detract from my findings in the Main Judgment that it was the look of the garments in photographs that attracted custom;

(c) In buying a particular garment from either side, the customer is buying into a “lifestyle” - both sides offered the same lifestyle; and

(d) There was no evidence that any comparable garments were available to customers of the Defendants at the relevant time and at comparable prices.

- There is no doubt in my mind that at least some of the infringing sales were sales lost by the Claimants. It is therefore clear to me that P > 0. As the parties each relied on the same evidence and submissions in relation to both stages of the relevant test, I will discuss the submissions of both sides in the context of establishing the value of P.

What is the Value of P?

- I was not assisted in the task of determining P by the diametric positions initially taken by the parties, with the Claimants suggesting that P was the maximum it could be (1), and the Defendants insisting that P was the minimum it could be (0). By their closing submissions, the Claimants had shifted, suggesting that P = 0.25. The Defendants continued to maintain that P = 0.

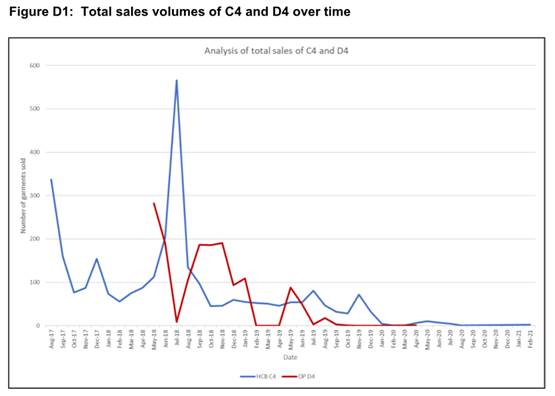

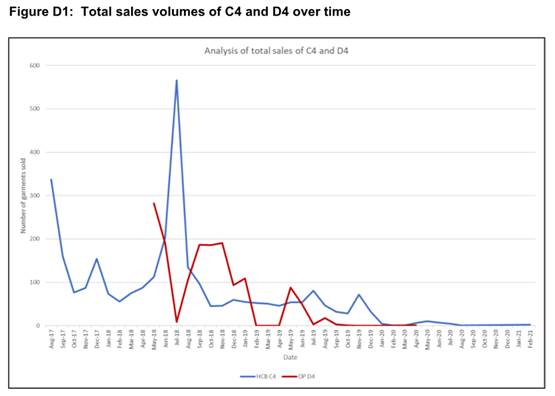

- Whilst there were 18 infringing garments, I have not assessed a different value for P for each garment. Counsel for the Claimants did not urge me to do so. Counsel for the Defendants submitted that P = 0 for each garment, and urged me to look at each design/garment pair individually to assess lost sales. Whilst not calculating a different value for P for each design/garment pair, I do accept counsel for the Defendants’ submission, and I have done that. I have also, as requested, reviewed carefully the helpful table provided by the Defendants and Mr Dearman’s Appendix C which compares the sales data as between the Claimants’ and the Defendants’ garments. It would, in my judgment, be inconsistent with the authorities I have cited above and grossly disproportionate to come up with 18 different values for P. I have therefore given P a single value, but I have taken into account the review I was asked by the Defendants to undertake, as well as the other submissions made on their behalf.

- The following facts were common ground:

(a) The infringing garments were copies of the Claimants’ garments (or parts of the Claimants’ garments);

(b) The businesses of both the Claimants and the Defendants sell garments to fashion-conscious young women who are looking to buy sexy clothing online and, in particular, dresses for a night out;

(c) The Defendants (at the relevant time) considered House of CB to be their biggest competitor;

(d) There are some customers who buy from both House of CB and Oh Polly; and

(e) The Defendants’ retail prices for infringing garments were, generally speaking, lower than those of the corresponding garment of the Claimants.

- Further, the Claimants have conceded that there would have been no substitute sales as between C108* (a swimsuit) and D41 (a jumpsuit).

- I turn now to the Defendants’ submissions that P = 0:

(a) The Defendants denied that the Claimants’ garments were selected to copy specifically because they were House of CB or Mistress Rocks garments, or those of a competitor more generally. Rather, counsel for the Defendants submitted that they were selected because they were “on trend”. I do not consider that this matters one way or the other in circumstances where the Defendants have conceded that they copied (or have been found to have copied) the Claimants’ garments because they were “on trend” - that is, highly desirable. I therefore do not take this into account, although, were I to do so, it would not make a meaningful difference;

(b) The Defendants denied that they considered Mistress Rocks their biggest competitor. This is said to matter because two of the infringing garments copied were Mistress Rocks garments - and the Mistress Rocks brand was different to the House of CB brand, targeting different consumers. I accept this submission and take it into account in my overall assessment;

(c) Whilst the Defendants conceded that there was some customer overlap between House of CB and Oh Polly, the Claimants accepted that there is not complete overlap. I accept that submission and I take it into account;

(d) The Defendants submitted that the difference in price between the Claimants’ garments and the Defendants’ garments was such that a significant proportion of the Defendants’ customers could not afford to buy one of the Claimants’ garments, especially at the undiscounted price. I accept this submission to a degree, but consider that it was overstated by the Defendants. The Claimants led evidence of discounting of their garments, in some cases deep discounting, such that the cost differential lessened, and in some cases, was removed. There was an overlap in customers - some customers bought garments from both businesses. I take this into account in my overall assessment;