Mr Justice Rajah :

Introduction

1. This is my judgment after a trial of an action for breach of confidence, infringement of trade secrets, breach of contract and copyright infringement. The judgment is confined to issues of liability and does not deal with quantum.

2. The Claimant (“IX”) is an advisory and broking boutique which specialises in illiquid investments. By 2019 it had particular expertise in Venezuelan debt. Its founders and directors are Celestino Amore and Galina Alabatchka. The First Defendant (“Altana”) is an investment fund management company. Its founder, controlling shareholder and Chief Investment Officer is Lee Robinson, the Second Defendant. The Fourth Defendant (“Brevent”) is a company that provides consulting services to Altana, of which Steffen Kastner, the Third Defendant, is the sole director and shareholder.

3. IX, Altana and Brevent entered into a joint venture to set up a fund to be called the Altana IlliquidX Canaima Fund (“AICF”) to invest in Venezuelan distressed debt (“the JV”). They signed a letter setting out the terms of the joint venture on 28 June 2019, as well as a non-disclosure agreement signed on 8 July 2019 (the “NDA”).

4. The joint venture had ended by the end of November 2019 without a fund being launched. Altana went on to set up its own fund focussed on distressed Venezuelan debt in July 2020. This was called the Altana Credit Opportunities Fund (“ACOF”).

5. IX says that in setting up the ACOF the Defendants misused IX’s confidential information and trade secrets. It also says that the Defendants marketed the ACOF using a slide presentation which infringed IX’s copyright.

The Issues

Breach of confidence

6. Although equitable duties of confidentiality are pleaded, the primary issue in this case is whether there has been a breach of contract - in particular whether there has been a misuse by the Defendants of IX’s confidential information as it is defined by the NDA and contrary to the terms of the NDA. There is an important carve out in the NDA which has the effect that information which is in the public domain cannot be protected as confidential information under the NDA.

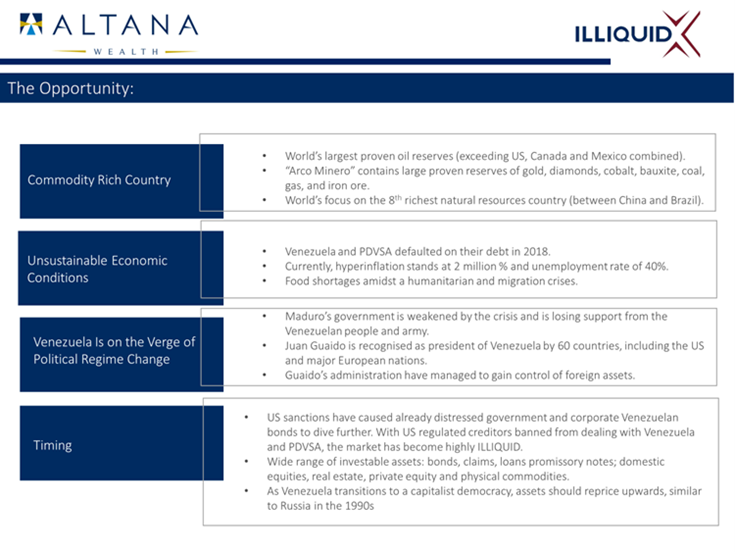

7. IX’s pleaded case is that it presented the Defendants with a package of confidential information which it calls “the Business Opportunity”. It says that the Business Opportunity was that there were distressed Venezuelan credit opportunities which the market “had ignored and/or avoided and/or undervalued” because of international sanctions restrictions on Venezuela, but that such credit opportunities could, upon application of IX’s investment strategy, be monetised and exploited for value notwithstanding those sanctions restrictions. The Business Opportunity is also alleged to be itself confidential information whether or not any part of the package of information it comprises (which it calls “the Detail”) is confidential.

8. The Defendants say that IX’s pleadings fail to identify with sufficient precision the Business Opportunity or its constituent parts so that it can be protectable. The Defendants also say that there is nothing in the Business Opportunity or the Detail which they can be proven to have used which was not already known to them or in the public domain. In this regard the Defendants rely on the fact that IX itself (before the JV), and IX and the Defendants (during the JV), publicised the Business Opportunity and substantially all of the Detail by circulating promotional materials to potential investors. The effect of that publication is an important issue in this case.

Trade Secret

9. IX says that the Business Opportunity was also a trade secret and breach of the NDA in respect of the Business Opportunity will also constitute an infringement of the Trade Secrets (Enforcement, etc.) Regulations 2018 (the “Regulations”).

Copyright

10. IX brings a claim for infringement of its copyright. Initially it claimed that a marketing presentation for the ACOF reproduced a marketing presentation for the AICF. That claim has been abandoned. What remains is a claim that parts of two slides from another IX presentation (the “17 July Slides”) were reproduced in the marketing presentation for the ACOF. So does IX’s claim that there has been secondary infringement by Mr Robinson and Mr Kastner personally in knowingly dealing with an infringing copy. The Defendants accept that two slides in an ACOF presentation reproduce parts of two slides of the 17 July Slides but dispute that there has been a reproduction of a substantial part of the 17 July Slides. In any event, they say, emails exchanged at the end of the JV amount to the grant of a licence to them to use the marketing materials IX had shared with them. In the alternative, Mr Robinson and Mr Kastner deny having the requisite knowledge that the ACOF presentation was an infringing copy.

11. If the alleged copyright infringement is established, IX will seek additional damages under section 97(2) Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (“CDPA 1988”) which provides that such damages as the justice of the case may require may be awarded having regard to all the circumstances and in particular a) the flagrancy of the infringement, and b) any benefit accruing to the defendant by reason of the infringement. That, however, is a matter for any further hearing on quantum and outside the scope of this judgment.

Joint liability

12. In respect of any wrong it establishes IX claims that Mr Robinson and Mr Kastner are also personally liable as accessories. In light of pragmatic concessions made by the Defendants the principal issue here is whether Mr Kastner is jointly responsible for wrongs committed by Altana, Brevent or Mr Robinson.

The Trial, Evidence and Witnesses

13. The trial took place between 4 October 2024 and 23 October 2024 with some non sitting days allocated to judicial pre-reading or the preparation of closing submissions.

14. Mr Amore and Ms Alabatchka were IX’s principal witnesses who were cross-examined at length. IX also called Mr Raphael Kassin and relied on the witness statement of Mr Coleman (the Defendant declining the opportunity to cross examine Mr Coleman) but their evidence was of limited relevance. The Defendants relied on the evidence of Mr Robinson and Mr Kastner who were also cross-examined at length.

15. It is now widely known, and pointed out in the Civil Procedure Rules, that human memory is not a “snapshot” which fades with time but is fluid and malleable and vulnerable to being altered by a range of influences; see CPR PD57AC. The process of civil litigation itself subjects the memories of witnesses, particularly witnesses who are parties, to powerful biases and influence, which may not be conscious; see Gestmin SGPS SA v Credit Suisse (UK) Ltd [2013] EWHC 3560 per Leggatt J at [19]. It is perfectly possible for an honest witness to have a firm memory of events which the witness believes to be true, but which in fact is not correct. The approach I take is to weigh each witness’s evidence in the context of the reliably established facts (including those which can be safely distilled from contemporaneous documentation bearing in mind that the documentation itself may be unreliable or incomplete), the motives and biases in play, the possible unreliability or corruption of human memory and the inherent probabilities.

16. In this case the trial bundles contain several thousand pages of contemporaneous documentation whose authenticity and reliability are not in question, although there are disputes as to what may have been meant or ought to be inferred from some of them.

Celestino Amore

17. Celestino Amore is the CEO and managing director of IX which he founded with his partner Galina Alabatchka in 2009 after a 12 year career in financial institutions in London and Rome. He was an honest witness but it was clear that his evidence was coloured by a sense of grievance and a considerable degree of reconstruction from the documents as to what he thinks must have happened. Some of that reconstruction was flawed. For example, the documents show that contrary to the assertion in his witness statement, AV Securities had been introduced to the joint venture partners as a potential custodian by Mr Robinson’s contact and not by IX.

Galina Alabatchka

18. Galina Alabatchka is a director and founder of IX. She also had a prior career over 11 years in financial institutions mainly in London and latterly in financial research and teaching. She was an honest witness who gave careful answers. Her witness statements had a tendency to overstate matters which she readily accepted in cross examination. For example, for the purposes of IX’s copyright claim her second witness statement describes how she, Mr Amore and one of IX’s full-time analysts, Reinaldo Azancot, prepared the 17 July Slides and the three of them coined phrases to use in the two slides relied on and created them from scratch. However, in cross-examination it became clear that the phrases had come from previous presentations and much of the two slides had been copied from earlier presentations and not been prepared from scratch. As with Mr Amore there was a considerable degree of reconstruction from the documents as to what must have happened rather than there being a genuine recollection.

Lee Robinson

19. Mr Robinson has worked in the City since 1991. He set up his own hedge fund business in 2001 and in 2010 set up the Altana group of companies. Altana launches and manages investment funds comprising Mr Robinson’s money and that of other investors. The funds invest in a wide range of opportunities - from cryptocurrencies to corporate bonds.

20. It was a strong theme of Mr Robinson’s evidence that he had superior expertise and knowledge such that he had nothing to learn from IX and he was dismissive of Mr Amore and Ms Alabtachka. His witness statement proclaims his exceptionality. “I am not an ordinary credit investor” he says, explaining that he is one of the very few who had foreseen the 2008 credit crisis and made great profit and received industry awards as a consequence. He says he is known as an expert in the industry, and has appeared on the cover of the Eurohedge and Hedge Fund Journal. The tenor of his evidence was that Ms Alabatchka and Mr Amore are not in his league, describing the latter as “a typical hustler broker”.

21. He claimed to be amply familiar with the existence and exploitability of Venezuelan debt prior to any contact with IX and that he had nothing to learn from IX. He claimed to have had a clear view, prior to contact with IX that he would be interested in investing in Venezuelan debt when it hit a price of 15 cents per dollar of debt. He claimed that he and Altana had conducted significant research into Venezuelan debt prior to the NDA with IX and they independently verified anything IX told them. All these claims are not consistent with the contemporaneous documentation; see paragraph [38] below and I found his explanations in cross examination not credible. Mr Robinson explained contemporaneous documents showing him asking questions apparently displaying his unfamiliarity and lack of knowledge of Venezuelan debt, as his asking probing questions (the answers to which he knew) to test IX’s knowledge. Mr Green called this the “test the rookies” explanation. I reject the “test the rookies” explanation - it is quite clear to me that in relation to Venezuelan distressed debt, Mr Amore and Ms Alabatchka were the experts and Mr Robinson and Mr Kastner were the novices. Mr Robinson said as much to investors - see for example his email of 16 September 2019 to Mr van Dam of Hampstead Capital, which said that he must “really meet [Mr Amore and Ms Alabatchka] to understand the details as they are the experts.” As for the target price of 15 cents, when taken to correspondence in July 2019 indicating Mr Robinson’s interest in investing himself if prices fell below 20 cents (thereby contradicting the notion that he had already fixed a target of 15 in his mind by April 2019) he became evasive and was ultimately unable to explain this contradiction.

22. Mr Robinson’s witness statement pointed to a mistake made by Mr Amore in an email on 6 September 2019 when Mr Amore referred to the first date for prescription becoming an issue in relation to a Venezuelan bond as July 2020 instead of October 2020. As part of the image of superior knowledge and expertise, Mr Robinson’s witness statement claimed that he had spotted this mistake at the time, but had chosen to say nothing. Having seen Mr Robinson in the witness box and seen his style and approach in the contemporaneous documents, it seems to me inherently unlikely that if Mr Robinson had spotted an error on the part of Mr Amore that he would not have said so immediately by email. In fact, there is no email or other record of Mr Robinson noting this mistake. On the contrary, in a conversation with Mr Amore a month later he appeared to think that prescription would be an issue in April 2020 rather than October 2020.

23. As part of this theme of superior knowledge and expertise, he disputed IX’s case that Mr Amore and Ms Alabatchka had advised Mr Robinson and Mr Kastner that they should obtain a legal opinion on US sanctions to reassure investors and institutions dealing with them. In his witness statement he claimed it as his idea arising from the fact that by August 2019 the joint venturers had found financial institutions were wary of providing corporate services to a fund in relation to Venezuela because of the US sanctions. That is not how it was put in Altana’s pleadings (which itself is not borne out by the contemporaneous documents) and it is not consistent with the contemporaneous documents. For example, a meeting note (the Due Diligence Note - see paragraph [41]) shows that a “Legal Opinion from Washington based lawyers that our structure/fund set up is compliant with US and European sanctions; likely Davis Polk” had been discussed at the first meeting after the NDA on 9 July 2019, and before Mr Robinson began approaching financial institutions looking for a custodian. When this was put to him in cross examination, Mr Robinson, unlike the other witnesses who had said things which were shown not to be correct, did not accept that his witness statement was wrong. Mr Robinson instead asserted, for the first time, that the statement in the Due Diligence Note emanated from him. When Mr Kastner, who prepared the Due Diligence Note, was asked in cross examination whether Mr Robinson’s evidence on this issue was truthful, there was an inordinately long pause before he declared that he could not remember. He accepted that he had never previously heard Mr Robinson assert that Mr Robinson had come up with the idea at the 9 July 2019 meeting. In fact, Davis Polk were IX’s contact and it was Ms Alabatchka who took matters forward with them. The correspondence shows that it was Ms Alabatchka and Mr Amore who were pushing for the opinion while as late as August 2019 Mr Robinson remained sceptical as to whether a lawyer would give a clear and unqualified positive opinion, and he was reluctant to incur the cost. He argued against obtaining an opinion. It was only in late August, when he realised there would be difficulties in obtaining an administrator and custodian, that he reluctantly agreed that the cost should be incurred. The legal opinion was not his idea.

24. This is a convenient point at which to mention one other matter which in my judgment affects Mr Robinson’s credibility. On 28 August 2020 Fieldfisher wrote a letter of claim on behalf of Mr Robinson and Altana under the relevant pre-action protocol to IX’s solicitors threatening proceedings for defamatory statements made by Ms Alabatchka about Mr Robinson to Mr Kastner. The premise of the claim was that these statements had caused Mr Kastner to reduce his investment in ACOF by between $2m and $6m. Mr Robinson produced a schedule which was sent with the Fieldfisher letter calculating the loss to Altana as a consequence on a number of permutations - producing a range from $815,858 to $8,663,245. Fieldfisher’s letter requested proposals for compensating Altana in respect of this loss. In fact, there is no evidence that the defamatory statement had any effect on Mr Kastner. A week after the letter, Mr Kastner signed a consultancy agreement on behalf of Brevent for the provision of Mr Kastner’s consultancy services to Altana to, amongst other things, set up the ACOF. Mr Robinson admitted in cross examination that he had simply made up the numbers. This was a significant lie to found a false claim to bully Ms Alabatchka and IX.

25. I am unable to accept anything said by Mr Robinson unless it is corroborated by the contemporaneous documents.

Steffen Kastner

26. Mr Kastner was at Goldman Sachs for about 20 years until 2014. Thereafter he has pursued his own investments and taken on consultancies from time to time. Brevent is the vehicle through which he provides consultancy services to Altana Wealth primarily in relation to a fund (ASIP) that is not relevant to this case. Brevent receives a 30% share of Altana’s profits from ACOF. Mr Kastner does not claim to do very much in relation to ACOF for this remuneration even though he is named as a member of its investment advisory committee.

27. Mr Kastner was an honest witness who gave careful evidence in the witness box. He too is guilty of reconstructing events from the documents. He had to accept in cross examination that in his witness statement he had rewritten history. He claimed a specific recollection that a phrase he is recorded as using (“investment value chain”) in a conversation on 18 April 2019 with Mr Amore and Ms Alabatchka was a reference to the type of investment he knew Mr Robinson was interested in (trade claims), but had to accept that was impossible because he had at that date not yet made contact with Mr Robinson.

28. Mr Kastner did not claim to have had ample familiarity with Venezuelan distressed debt prior to meeting IX. He said he had a general understanding of the situation in Venezuela and that there would be distressed debt. Prior to first contact with IX he had never purchased a Venezuelan sovereign or PDVSA bond. Brevent had never done any research into Venezuelan debt. He accepted that until IX made contact with him, Venezuela was not on his investment radar.

The Facts

Venezuela

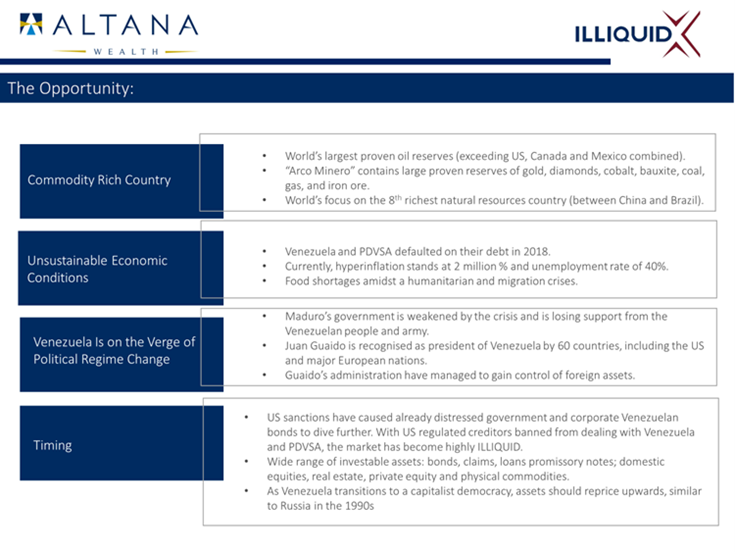

29. By 2019, most of Venezuela’s sovereign debt was in default.

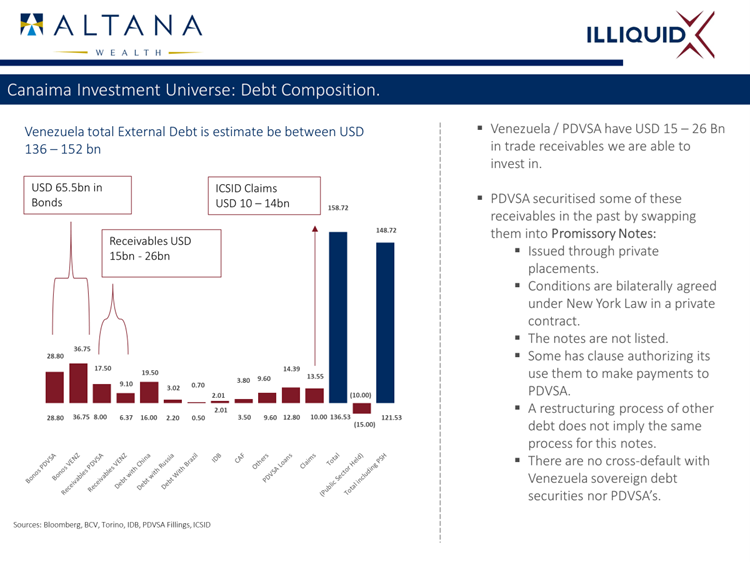

30. Despite the country’s enormous natural resources, a number of factors, such as the crash in oil prices in 2014, falling oil production and US sanctions, had led to a major economic crisis with hyperinflation, mass unemployment and mass migration of its population. There was political turmoil following a contested election in 2018 with some countries continuing to recognise Nicolás Maduro as president while others recognised his opponent, Juan Guaidó.

31. The United States of America had imposed sanctions restricting Venezuela’s access to US financial markets in 2017-2018, with certain exceptions to minimise the impact on US economic interests. Those exceptions allowed US investors and financial institutions to continue to buy and sell certain Venezuelan sovereign bonds and bonds issued by the Venezuelan state oil company Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (“PDVSA”) in the secondary market.

32. All that changed in January and February 2019. On 28 January 2019, PDVSA was sanctioned, freezing its US assets and prohibiting US persons from dealing with it without a licence from the Office of Foreign Assets Control (“OFAC”) and restricting US persons’ dealings in PDVSA bonds so that only divestments to a non-US person were permitted. Shortly afterwards, on 1 February 2019, the previously broad exception for secondary market dealings in Venezuelan sovereign bonds was narrowed in the same way, so that US persons (i.e. most of the market) could not buy the bonds, and could only sell them to non-US persons. On 11 February 2019, the General Licenses were amended again to make clear that US persons could not “facilitate” the purchase of listed bonds, other than divestments to non-US persons.

33. The position was much the same in respect of trade claims. After 2019, a US person would have been prohibited from buying or selling any trade claims against the Government of Venezuela or PDVSA without an OFAC license.

34. These sanctions distorted the market in respect of Venezuela and depressed the price of bonds. It remained possible for non-US persons to buy and clear 38 Venezuelan sovereign and PDSVA bonds from US sellers through Euroclear without breaching US sanctions. It remained possible for non-US persons to deal in non-US trade claims against the Government of Venezuela or PDVSA. There is no dispute that this created an investment opportunity.

Illiquidx’s idea

35. Since 2009 IX’s business has been focused on advising and trading in distressed debt with its own capital and as a broker on behalf of clients. Prior to its relationship with the Defendants, IX had been looking to set up an investment fund to invest in Venezuelan distressed debt. IX had made presentations, including a 106-slide presentation about Venezuela (the “Venezuela Data Slides” - item (c) of the Detail relied upon by IX) which recorded factual data about Venezuela. It had also prepared a more focussed slideshow presentation (“the Canaima Capital Presentation” - item (a) of the Detail) which set out the nature of the proposed fund and why it was a good investment opportunity. IX circulated various iterations of the Canaima Capital Presentation in February and March of 2019 to a number of potential investors to encourage interest in the proposed fund.

First contact with Mr Kastner and Mr Robinson

36. Ms Alabatchka had previously worked with Mr Kastner at Goldman Sachs and the two had remained in intermittent contact. At a meeting with him on 5 April 2019, Ms Alabatchka shared IX’s plans to set up an investment fund in relation to Venezuela and raise capital. A telephone call was arranged between Mr Amore and Mr Kastner on 18 April 2019. In that call, Mr Amore explained IX’s intentions of setting up a fund trading in distressed sovereign debt and why. Mr Kastner suggested Mr Robinson as a potential person that IX could work with to source capital.

37. On 30 April 2019 Mr Amore sent Mr Kastner the Canaima Capital Presentation and on 8 May 2019 Mr Robinson reviewed it. On 10 May 2019, Mr Amore, Mr Robinson and Mr Kastner had a conference call to discuss it. On 29 May 2019 Mr Robinson emailed Ms Alabatchka and Mr Amore with Altana’s proposal for providing set up and operational support for a fund with a commitment to lead marketing and raise capital for the fund, and a proposed fee structure.

38. Despite Mr Robinson’s protestations otherwise, it is clear from the contemporaneous evidence that Mr Robinson and Mr Kastner (the latter does not contend otherwise) had very little idea about Venezuelan debt at this point in time. For example:

i) the transcript of the 18 April 2019 call between Mr Amore and Mr Kastner reads like a one-way tutorial. Mr Kastner does not appear to have known anything about sanctions, their impact on US investors, or that bonds could still be bought by non-US persons. He did not know about PDVSA or that it was 100% owned by the Venezuelan government. He could, however, see the opportunity once it was explained.

ii) On reviewing the Canaima Capital Presentation Mr Robinson’s email to Mr Kastner shows he was sceptical as to whether it was possible to get around US/EU sanctions - in other words he did not at that stage know that Venezuelan sovereign bonds and PDVSA bonds could be traded despite the sanctions in place.

iii) The transcript of the 10 May 2019 call shows Mr Amore explaining to Mr Robinson, who did not know how certain Venezuelan bonds could be traded through Euroclear and how the EU sanctions operated. Mr Robinson appeared to have no knowledge that the bonds could be traded, who was permitted to trade the bonds, or how the trades could be executed.

iv) On 4 June 2019, when discussing fee splits regarding the JV, Mr Kastner said to Mr Robinson: “I think we both acknowledge that we need them more than they need us to get this off the ground. We don’t really have an alternative to them at this stage for Venezuela whereas they are more likely to find a backer.”

The JV and NDA

39. The parties entered the JV and signed the NDA shortly thereafter on 28 June 2019 and 8 July 2019, respectively.

40. The JV is in the form of a letter from Altana to Ms Alabatchka and Mr Amore which is signed by them on behalf of IX, by Mr Robinson on behalf of Altana and by Mr Kastner on behalf of Brevent. It states the opportunity being explored as the creation of “a joint funding vehicle to pursue distressed investing opportunities in Venezuela”. It envisaged the immediate next steps as (1) putting in place an NDA and non-circumvent agreement; (2) due diligence of IX’s potential trades and IX’s resources available; (3) a short teaser presentation for marketing; and (4) an exclusive period until 15 October 2019 for Altana to raise $30m of soft commitments to invest.

41. After executing the NDA, the parties held a meeting on 9 July 2019, which Mr Kastner recorded in the form of notes (the “Due Diligence Note” - item (b) of the Detail). Mr Kastner distributed the Due Diligence Note on the same day. I prefer the evidence of Mr Amore and Ms Alabatchka as to this meeting and this note. This was a “dump” of information by IX on Altana now that the NDA had been signed. Mr Amore talked through the US and EU sanctions and the mechanics and feasibility of various types of trade, recovery strategies, and the possible competition. His briefing included the idea of obtaining a legal opinion that the fund was sanctions compliant to reassure investors and financial institutions dealing with the proposed fund.

42. On the same day, Ms Alabatchka followed up with an email to Mr Kastner attaching the Executive Orders and General Licenses containing the US sanctions regime (the “9 July Email” - item (b1) of the Detail). The annexes to the General Licenses identified the universe of 38 Venezuelan bonds which non-US investors could lawfully buy from US sellers pursuant to the US sanctions.

43. Thereafter there were many emails and conversations between Messrs Robinson, Kastner, Amore and Ms Alabatchka and the remaining documents forming part of the Detail were sent to Mr Robinson and Mr Kastner. I will not mention them all in the body of this judgment but the Schedule contains a list and brief description of each item of the Detail.

44. Mr Amore told Mr Robinson and Mr Kastner that many banks would not trade Venezuelan bonds because of the US sanctions, giving the joint venture an edge over them. Mr Kastner and Mr Robinson were sceptical and so Mr Kastner put this to the test by asking his bank Pictet if Pictet could source and trade Venezuelan sovereign and PDVSA bonds (the “Pictet experiment”). The response on 22 July 2019 was they were not allowed to do so because of the US sanctions. Mr Amore responded jubilantly “we are ahead… huge market for our product”. Mr Kastner accepted in cross examination that the “product” was a fund which could invest in Venezuelan bonds. The Pictet experiment shows that bonds were a significant part of the JV’s focus - the significance of this is discussed later.

45. As envisaged by the JV letter the parties worked on preparing “teaser” presentations for marketing. This culminated in the production by IX of a fact sheet summarising the terms of the proposed fund (the “Canaima Fund Fact Sheet”– item (m) of the Detail) and a PowerPoint presentation encouraging investment in the proposed fund (the “AICF Presentation” - item (l) of the Detail). There were earlier iterations of these documents sent to Mr Kastner and Mr Robinson and which form part of the Detail - the 12 August Fund Fact Sheet and the 17 July Slides.

46. Mr Robinson and Mr Kastner were by this stage fully persuaded of the lucrative nature of the opportunity. After his initial scepticism, by the end of July 2019 Mr Robinson was describing Venezuelan distressed debt to potential investors in the AICF as “the best distressed sovereign trade I have ever seen” and “the distressed trade of the decade”.

47. Notwithstanding the fact that the JV was in full swing, by the end of August 2019 Mr Kastner and Mr Robinson were privately discussing between themselves whether they had sufficient information to go it alone without IX. On 21 August 2019, following an email from Mr Amore about ‘next steps’, Mr Robinson said to Mr Kastner that “[t]his email by him is good enough for what we discussed last week and potentially go alone.” Mr Robinson was, however, concerned about the fact that they still had not been able to secure a custodian for the fund. Potential custodians were wary of contravening US sanctions.

48. At about this time AV Securities was identified as a potential custodian. Although Mr Amore claimed AV Securities as one of his contacts, they were in fact introduced to the joint venture by Juan Argento who was a contact of Mr Robinson. On 17 September 2019, Mr Argento provided Antonio Ciulla’s contact from AV Securities to Mr Robinson, with Mr Amore in copy. Mr Robinson, Mr Amore and Mr Ciulla then had a phone call on 27 September 2019 to discuss AV Securities’ suitability.

49. On 24 September 2019, Ferrari & Associates provided a legal opinion addressed to both Ms Alabatchka and Mr Robinson, pursuant to a joint instruction by Altana and IX, to the effect that the proposed fund would not contravene US sanctions (the “Ferrari Opinion” - item (v) of the Detail).

50. For the purposes of the JV, a segregated portfolio company in the Cayman Islands, with the name Canaima SPC, was incorporated by Altana on 17 September 2019.

51. Mr Amore, Ms Alabatchka, Mr Robinson and Mr Kastner had a telephone call with Professor Olivares-Caminal on 5 September 2019. Professor Olivares-Caminal is a legal academic specialising in sovereign debt and Mr Amore describes him as a “well- known figure in the distressed emerging markets space”. The Defendants accept that Professor Olivares-Caminal was IX’s pre-existing contact.

52. On the phone call, Professor Olivares-Caminal and Mr Amore explained that Venezuelan bonds used a fiscal agency rather than trust structure. This meant that to stop claims to interest or capital becoming time barred legal proceedings had to be brought by the individual bond holder. This was important because historically, sovereign nations had not taken limitation or prescription points, but Argentina had recently done so and Professor Olivares-Caminal considered it realistic that Venezuela would do so too. The significance of this point was important to the joint venture. Firstly, the ramifications of Venezuelan bonds being a fiscal agency structure were not well known. Nor was the analysis that protective legal proceedings should be commenced. Further, a big advantage and selling point of the new joint venture fund was that it could bring such protective proceedings on behalf of all its investors. This was a point Mr Amore said was already in the marketing presentation, but Mr Kastner and Mr Robinson thought more should be made of it. Mr Robinson described it as having “a diamond” which they needed to get people to see.

53. Following this call, on 6 September 2019, Mr Amore sent an email to the JV participants, with a summary about Venezuelan and PDVSA prescription on interest and capital (“6 September Email” - item (i) of the Detail) and how soon limitation periods might start to expire (October 2020). On 11 September 2019, Professor Olivares-Caminal provided a short one-page note on the effect of limitation periods on Venezuelan bonds and the consequential advantage of the proposed joint venture fund which could protect investor rights (the “Limitations Document” - part w(i) of the Detail). Professor Olivares-Caminal produced a memorandum dated 2 October 2019 and addressed to Mr Amore, Ms Alabatchka and IX (the “Trustee vs Fiscal Agent Memo” - item (w)(ii) of the Detail) explaining the difference between trustee and fiscal agency structures in sovereign bonds. Slide 12 of the AICF Presentation was prepared to highlight the fiscal agency/prescription issue to potential investors.

54. On 11 October 2019 Mr Amore sent Mr Robinson and Mr Kastner a further PowerPoint presentation (the “Claim Management Presentation” - part (r) of the Detail) which explained the proposed multi-cell structure of the AICF which would allow existing holders of Venezuelan debt to invest in kind in the AICF by exchanging their debt for shares in the relevant cell of the AICF. This presentation explained the protection conferred by the multi-cell structure and the advantages of the AICF being able to bring litigation on behalf of all investors.

55. On 28 October 2019, Mr Amore and Mr Robinson had a phone call with four people from Mercantil Bank, exploring the option of using Mercantil as a potential custodian (“Mercantil Call”). In that call, Mr Robinson explained the JV Fund as a “segregated protected cell… we set this up originally from an idea by Celestino to take advantage of what we think are incredibly cheap assets in Venezuela bonds and PDVSA bonds.” Mr Robinson also explained the “angle” as follows:

“No, we are pitching initially to people who want to be involved in the trade, and it’s not obvious to outsiders, but it is obvious to Celestino and now to myself now he’s educated me - is that, due to the previous precedents, there is a risk that if you just buy these bonds in your private bank account in Switzerland or wherever you’ve got a private bank account, you may not –that private bank will not do anything for you. They will not make claims, they will not go through the process and, therefore, you could lose the principal, which is rolling up at, you know, 7 to 13 per cent, depending on the bonds, and you may also lose the principal as well, and you know, given that the previous precedent with Argentina, that’s a risk that you don’t want to take as an end investor.” [Emphasis added]

56. The parties reached an impasse on the proposed JV fund structure and their respective roles in the AICF, and the JV fell apart in early November 2019. In an email exchange on 5 November 2019 Mr Kastner and Mr Robinson were sanguine about the prospect of the JV ending, concluding that a JV with IX was “probably not worth it” and that going it alone would result in “twice the pie” for the two of them. Mr Robinson observed that he would have preferred IX to do the legwork “but for multi millions in perf fees I am happy to do it”.

57. On 6 November 2019, Mr Amore emailed Mr Robinson asking that “all data, figures and docs exchanged with you will not be used for any further marketing material or with third parties”. Mr Robinson responded saying he would “remove any items that are proprietary” but that he believed there was none in the marketing materials. Mr Robinson asked Mr Amore to “list all data, figures and docs” that he believed were proprietary. Mr Amore did not respond.

After the JV

58. Mr Robinson continued setting up the fund envisaged by the JV. It was to become the ACOF. On 8 November 2019, Mr Robinson sent the Canaima Fund Fact sheet to a potential custodian, but now referring to it as “my Venezuela fund”. On 19 November 2019, Mr Robinson shared the Ferrari Opinion with a potential custodian in an attempt to obtain a custody account for his new fund. On 10 December 2019, Mr Robinson returned to his communications with Mr Ciulla from AV Securities, taking Mr Amore off copy, to ask whether there was “a potential solution with AV securities.” AV Securities opened a custody account for Altana in January 2020.

59. Outwardly, the parties’ relationship remained amicable, maintaining occasional contact, and the door to working together remained open until March 2020. On 19 February 2020, Mr Amore and Mr Kastner had a phone call, in which Mr Kastner expressed that Mr Robinson’s preference was still to do the JV together, an offer which Mr Amore eventually declined.

60. Altana made no attempt to conceal from the Defendants that it was launching a fund. In the 19 February 2020 call, Mr Kastner informed Mr Amore that Mr Robinson had continued to pursue the opportunity. When Mr Amore said that he was focusing more on bonds, Mr Kastner explained that Mr Robinson was focusing more on bonds as well. Also in February, Mr Amore emailed Mr Robinson saying, “great to see that you [are] already operative.”

61. On 3 March 2020, Altana distributed a marketing email for the ACOF (the “March ACOF Marketing Email”). That email referred to the “trade of the new decade: Venezuela” and advertised:

“While we’ve been talking about the trade since last summer it has taken us months to set up the fund.

· Very few custodians are willing to open new accounts even though we have a legal opinion clearly stating we are sanctions compliant

· We have renamed the fund avoiding direct mention of Venezuela

· We have now set up the necessary accounts and traded some bonds”

62. Mr Robinson accepted that the legal opinion referred to in the March ACOF Marketing Email is the Ferrari Opinion. The reference to “talking about the trade since last summer” is clearly a reference to the marketing of the AICF in the summer of 2019.

63. Upon receiving the March ACOF Marketing Email, Ms Alabatchka forwarded it to Mr Kastner complaining of plagiarism and saying, “even the presentation was ours”.

64. On 15 May 2020, Altana distributed another marketing email, announcing its intention to launch the ACOF, which included a presentation for the ACOF (the “May ACOF Marketing Email”). The marketing explained that the ACOF had hired legal advisors to file claims in court on investors’ behalf to protect against the statute of limitations. Ms Alabatchka, clearly upset at receiving this, sent angry emails to Mr Kastner expressing her feelings. Mr Kastner forwarded the email chain to Mr Robinson. It is this chain of emails which gave rise to the dishonest and bullying letter before action on behalf of Altana (paragraph [24] above).

65. IX’s claim was issued on 27 July 2020.

66. On 8 October 2020, the ACOF filed a claim in New York in respect of Venezuelan sovereign bonds that were governed by fiscal agency agreements.

Breach of confidence

The legal principles

67. The legal principles governing the duty of confidence were comprehensively reviewed by Mr Justice Hildyard in CF Partners v Barclays Bank [2014] EWHC 3049 (Ch) at [120] - [142] (“CF Partners”). I set out the parts of that review that are most relevant to this case below.

“120. Even in the absence of a contractual relationship and stipulation, and in the absence too of an initial confidential relationship, the law imposes a “duty of confidence” whenever a person receives information he knows or ought to know is fairly and reasonably to be regarded as confidential: see per Lord Nicholls (dissenting on the result, but not on this issue) in Campbell v MGN Ltd [2004] UKHL 22; [2004] 2 AC 457 at [14].

121. The subject matter must be “information”, and that information must be clear and identifiable: see Amway Corp v Eurway International Ltd (1974) RPC 82 at 86-87.

122. To warrant equitable protection, the information must have the “necessary quality of confidence about it”: per Lord Greene MR in Saltman Engineering Co Ltd v Campbell Engineering Co Ltd (1948) 65 RPC 203 at 215.

123. Confidentiality does not attach to trivial or useless information: but the measure is not its commercial value; it is whether the preservation of its confidentiality is of substantial concern to the claimant, and the threshold in this regard is not a high one: Force India Formula One Team Limited [2012] ROC 29 at [223] in Arnold J’s judgment at first instance.

124. The basic attribute or quality which must be shown to attach to the information for it to be treated as confidential is inaccessibility: the information cannot be treated as confidential if it is common knowledge or generally accessible and in the public domain. Whether the information is so generally accessible is a question of degree depending on the particular case. It is not necessary for a claimant to show that no one else knew of or had access to the information.

125. A special collation and presentation of information, the individual components of which are not of themselves or individually confidential, may have the quality of confidence: for example, a customer list may be composed of particular names all of which are publicly available, but the list will nevertheless be confidential. In the Saltman case (supra) Lord Greene MR said:

“…it is perfectly possible to have a confidential document, be it a formula, a plan, a sketch, or something of that kind, which is the result of work done by the maker on materials which may be available for the use of anybody; but what makes it confidential is the fact that the maker of the document has used his brain and thus produced a result which can only be produced by somebody who goes through the same process.”

Or as it is put in Gurry on Breach of Confidence (2 nd ed., 2012) para 5.16:

“Something that has been constructed solely from materials in the public domain may possess the necessary quality of confidentiality: for something new and confidential may have been brought into being by the skill and ingenuity of the human brain. Novelty depends on the thing itself, and not upon the quality of its constituent parts. Indeed, often the more striking the novelty, the more commonplace its components…”

…

127. The parties may by contract agree and identify specified information that is, or is as between the parties to be treated as, confidential, or protected under the terms of their agreement; or they may simply agree that information may not be used whether or not otherwise it would have the quality of confidentiality.

…

130. Contractual obligations and equitable duties may co-exist:

the one does not necessarily trump, exclude or extinguish the other: see Robb v Green [1895] 2 QB 315 and Nichrotherm Electrical Company Ltd and others v Percy [1957] RPC 207 (both in the Court of Appeal).

131. However, where the parties have specified the information to be treated as confidential and/or the extent and duration of the obligations in respect of it, the court will not ordinarily superimpose additional or more extensive equitable obligations: and see per Sales J in Vercoe and Pratt v Rutland Fund Management Ltd [2010] EWHC 424 (Ch), who found in that case that the duty of confidence was confirmed and defined by the contract, and observed (at [329]):

“Where parties to a contract have negotiated and agreed the terms governing how confidential information may be used, their respective rights and obligations are then governed by the contract and in the ordinary case there is no wider set of obligations imposed by the general law of confidence: see e.g. Coco v Clark at 419.”

…

138. To found a claim, whether in law or equity, actual misuse adverse to the claimant of information which still retains the quality of confidentiality must be established or inferred. For example, where a defendant had knowledge of a rival bid, through a relationship and information which could have been confidential, it was not sufficient, without more, to show that the defendant was “galvanised” by that knowledge into acting more speedily to use information that had not the quality of confidentiality, where by the time of that use the claimant’s rival bid was public knowledge, and was not shown to have been adversely affected by the defendant’s use of that knowledge: see Arklow Investments Ltd and Another v Maclean and Others [2000] 1 WLR 594.

139. Similarly, as it seems to me, the fact that the recipient’s perspective is changed by the confidential information he receives is not enough to constitute misuse, unless and until that change in perspective causes him actually to use that information otherwise than for the purposes for which it was provided to him.

140. Nevertheless, subconscious misuse will suffice: deliberate misuse does not have to be shown. But the confidant must have acquired the confidential information in circumstances where he has notice or is held to have agreed that the information is confidential: and see Attorney-General v Observer Ltd and Others (Spycatcher) [1990] 1 AC 109 at 281B per Lord Goff of Chieveley.”

The NDA

68. The NDA is in the form of a letter from Altana to IX which is signed by Mr Robinson on behalf of Altana and countersigned by way of acceptance by Mr Amore on behalf of IX and Mr Kastner on behalf of Brevent. It was drafted and amended primarily by Ms Alabatchka and Mr Kastner, but it is plainly based on a professionally drafted template or precedent.

69. The Court’s task in interpreting the NDA is to ascertain the objective meaning of its language. There are no alleged implied terms and no oral agreement is pleaded or relied on. The relevant legal principles are well established, as set out by the Supreme Court in Wood v Capita Insurance Services [2017] UKSC 24 and summarised by Leggatt LJ in Minera Las Bambas SA v Glencore Queensland Limited [2019] EWCA Civ 972 at [20]:

“The principles of English law which the court must apply in interpreting the relevant contractual provisions are not in dispute. They have most recently been summarised by the Supreme Court in Wood v Capita Insurance Services Ltd [2017] UKSC 24; [2017] AC 1173 at paras 10-14. In short, the court's task is to ascertain the objective meaning of the relevant contractual language. This requires the court to consider the ordinary meaning of the words used, in the context of the contract as a whole and any relevant factual background. Where there are rival interpretations, the court should also consider their commercial consequences and which interpretation is more consistent with business common sense. The relative weight to be given to these various factors depends on the circumstances. As a general rule, it may be appropriate to place more emphasis on textual analysis when interpreting a detailed and professionally drafted contract such as we are concerned with in this case, and to pay more regard to context where the contract is brief, informal and drafted without skilled professional assistance. But even in the case of a detailed and professionally drafted contract, the parties may not for a variety of reasons achieve a clear and coherent text and considerations of context and commercial common sense may assume more importance.”

70. I set out the relevant parts of the NDA here.

Preamble

71. It commences with these words:

“In connection with Altana Wealth Limited and its associated entities (together, “ALTANA”) and Brevent Advisory Ltd. (“Brevent”), and potential Venezuela related credit investment opportunities, including (but not limited to) Venezuelan government / corporate bonds and claims and other Venezuelan receivables, private equity and other such Venezuela related opportunities (“Opportunities”) to be sourced by Illiquidx Limited (“IlliquidX”), Confidential Information (as such expression is defined below) will be furnished between ALTANA and IlliquidX to their respective Representatives. As a condition to the furnishing of such Confidential Information, you hereby agree to the terms and conditions contained in this Confidentiality Letter (this “Letter”).”

Definitions

72. The NDA then sets out a number of definitions.

73. It defines confidential information for the purposes of the NDA (“Confidential Information”) as follows:

“Confidential Information” means any and all information relating to ALTANA and/or to IlliquidX and/or any Opportunities and which is considered by the disclosing Party to be of a confidential nature (or is marked or described as confidential) and furthermore includes, without limitation:

a) Information of whatever nature relating to ALTANA which is or has been furnished in oral, written, visual, magnetic, electronic or other form to IlliquidX or its Representatives by ALTANA or its Representatives, or which has been obtained by IlliquidX or its Representatives from ALTANA or its Representatives, in each case in connection with any of the Opportunities; and

b) information of whatever nature relating to IlliquidX or any of the Opportunities that Illiquidx introduces and/or presents to ALTANA or Brevent, whether eventually invested in or not, which is or has been furnished to ALTANA or Brevent, or to any of their respective Representatives, in oral, written, visual, magnetic, electronic or other form by IlliquidX or its Representatives, or which is or has been furnished by IlliquidX or its Representatives to ALTANA or Brevent, or any of their respective Representatives, in each case in connection with any Opportunities; and

c) information related to clients or contacts of ALTANA who cannot be approached by IlliquidX without ALTANA’s express permission;

d) information related to clients or contacts of IlliquidX who cannot be approached by ALTANA or Brevent without IlliquidX’s express written permission, including (but not limited to) Representatives, introduced third parties (individuals or entities) and investors; and

e) all IlliquidX Intellectual Property that is disclosed to, or obtained by, ALTANA or Brevent, or any of their respective Representatives, in connection with the Permitted Purpose or any of the Opportunities.”

74. IlliquidX Intellectual Property is given a wide definition which includes:

“any and all of the following forms and types of intellectual property which are created, developed, generated and/or owned by IlliquidX from time to time in connection with the Permitted Purpose or any of the Opportunities:

…

(ii) all ideas, concepts, transaction structures, reports, analysis, specification, copyright material and all equivalent, neighbouring or related rights …”

The operative provisions

75. The NDA then sets out eight numbered paragraphs containing the obligations it imposes. I do not need to refer to them all.

76. By Paragraph 1, Altana and Brevent were obliged “(a) to keep all Confidential Information confidential and not to disclose it to anyone […] save to the extent permitted by paragraph 1.1 below […] and (b) to use the Confidential Information only for the purpose of sourcing, evaluating and (as applicable) introducing and/or presenting Opportunities (the “Permitted Purpose”). Substantially the same obligations were repeated in Paragraph 1.2(a).

77. Significantly, the obligation in Paragraph 1 was qualified by Paragraph 1.1 which permitted disclosure of certain information, principally information in the public domain.

“1.1 Permitted Disclosure

The undertakings contained in this Letter shall not apply to any Confidential Information which:

a) At the time of supply is in the public domain;

b) Subsequently comes into the public domain other than as a result of a breach of the undertakings contained in this Letter;

c) at the time of supply is rightfully in the receiving Party’s possession or control or was independently developed by the receiving Party or its Representatives prior to disclosure of the same hereunder; or

d) subsequently comes into a Party’s possession or control from a third party who is rightfully in possession or control of it and is not bound by any obligation of confidence or secrecy to ALTANA, Brevent or IlliquidX.”

78. By Paragraph 2(b), Altana and Brevent were obliged,“[i]n the event the Parties elect not to pursue a business relationship related to any of the Opportunities”, not to “make any use of any other Party’s Confidential Information, including (but not limited to) any such Confidential Information relating to any of such other Party’s Representatives, introduced third parties (individuals or entities) and investors directly or indirectly, or through any other intermediary, whether affiliated with that Party or not until termination as per clause 7”.

79. Paragraph 3 of the NDA is a non-solicitation and non-compete clause:

“(a) None of the Parties shall approach, solicit, engage or hire, directly or indirectly, any of the other Parties’ Representatives who were introduced to that Party by any of those other Parties as part of the discussions relating to the Opportunities and/or the

Permitted Purpose, or whose details were shared as part of those discussions, until termination as per clause 7.

(b) The Parties are free to compete with each other in the event that any of them decide to not jointly pursue the Opportunities, except that neither ALTANA nor Brevent can compete against IlliquidX using any of IlliquidX’s Confidential Information including (without limitation) (i) any such Confidential Information which relates to any of IlliquidX’s Representatives, clients, contacts, investors or acquisition targets and/or to any of the Opportunities disclosed by IlliquidX to Altana and (ii) any IlliquidX Intellectual Property.”

80. All the obligations in the NDA were time limited. It is common ground that they expired on 8 July 2022.

Discussion of specific points

81. As appears above, the “Opportunities” are defined in the opening words of the NDA as “potential Venezuela related credit investment opportunities, including (but not limited to) Venezuelan government/corporate bonds and claims and other Venezuelan receivables, private equity and other such Venezuela related opportunities (“Opportunities”) to be sourced by Illiquidx Limited (“Illiquidx”)…”. The Permitted Purpose is the “sourcing, evaluating and (as applicable) introducing and/or presenting the Opportunities”. As a matter of construction of the whole document, the Opportunities are the specific opportunities within the general category of “potential Venezuela related credit investment opportunities” that were “to be sourced” by IX. It is common ground that apart from identifying 38 sovereign and PDVSA bonds which were suitable for investment (which I consider to be Opportunities), no specific opportunities were introduced or presented by IX to Altana and Brevent, although there was some discussion of specific opportunities by email.

82. It is common ground that the NDA applies to information passing between the parties to it before and after it was signed.

IX’s pleaded case

83. A claim for misuse of confidential information must identify with particularity the confidential information which has been misused. IX has struggled to do this. Its pleadings have been amended and reformulated several times and been the subject of correspondence, requests for further information and ultimately court decisions.

84. IX now sets out the confidential information on which it relies in its Re-Re-Amended Confidential Annex 1 to its particulars of claim (“RRACA1”). The present shape of RRACA1 is that the first half (from A1 to A12) describes a package of confidential information called “the Business Opportunity”, while the second half sets out what is referred to as “the Detail”. I ruled at the pre-trial review, Illiquidx Ltd v Altana Wealth Ltd [2024] EWHC 2385 (Ch), that the pleaded case is that the Business Opportunity is composed of the information listed in the Detail. The Detail comprises documents and is limited to the passages in the documents which are identified in the pleading.

85. According to RRACA1 “the Business Opportunity was that there were distressed Venezuelan credit opportunities (namely the Opportunities defined in the NDA) which the market (including the Defendants) had ignored and/or avoided and/or undervalued because of the OFAC sanctions restrictions on Venezuela, but that such credit opportunities could, upon application of IX’s investment strategy… be monetised and exploited for value notwithstanding the aforesaid sanctions restrictions”. According to RRACA1, IX’s “investment strategy” included establishing an OFAC sanctions compliant fund which was to be the joint venture vehicle for unlocking value in distressed Venezuelan debt.

86. Although paragraphs A2 to A11 of RRACA1 appear to set out other elements of IX’s investment strategy, Mr Green in his closing submissions sought to focus on the idea of a sanctions compliant fund. The Business Opportunity, he submitted, was the opportunity to set up a sanctions compliant fund to exploit undervalued Venezuelan debt. This was valuable because it was not common knowledge in the market that this could be done and IX had the know how to overcome the apparent obstacles in the way. I accept that this change of emphasis is within IX’s pleaded case, and Mr Moody-Stuart did not seek to argue otherwise. This is because a sanctions compliant fund as a means of unlocking value is described as part of the package of information comprising the Business Opportunity and confidential in its own right (see paragraphs A3(3), A6(3) and A12 of RRACA1) and it is contained in and evidenced by several documents comprising the Detail, such as the Canaima Capital Presentation, the 17 July Slides, the AICF Presentation and various fund fact sheets (see below and the Schedule).

87. So far as the Detail is concerned the Defendants accept that much of the information supplied to it by IX was Confidential Information for the purposes of the NDA but maintain that it was in the public domain. The Defendants accept that the Canaima Capital Presentation and various other presentations and documents which outlined the strategy of setting up a sanctions compliant fund to buy undervalued Venezuelan debt are Confidential Information for the purposes of the NDA, but maintain that this is information which was in the public domain.

88. The Business Opportunity was the focus of Mr Green’s submissions at trial. Little time was spent on the Detail. In this judgment, I too will focus on the Business Opportunity.

I have set out my findings in respect of each element of the Detail in the Schedule to this judgment.

89. Although both equitable and contractual duties of confidence are pleaded by IX, it was common ground by the end of the trial that only the contractual duties in the NDA are relevant. Contractual and equitable duties may co-exist. However, as Hildyard J observed in CF Partners, where the parties have specified the information to be treated as confidential or the extent and duration of the obligations in respect of it, the court will not ordinarily superimpose additional or more extensive equitable obligations; at [130-1]. It is also open to the parties to an agreement to agree more extensive obligations than might be imposed by equity.

Can IX identify Confidential Information given to the Defendants?

90. The Business Opportunity - the opportunity to set up a sanctions compliant fund to exploit undervalued Venezuelan debt - is Confidential Information as defined by the NDA because it was IX’s idea and concept and therefore was information “relating to Illiquid X” for the purposes of sub paragraph (b) of Confidential Information and was also within sub paragraph (ii) of the definition of IlliquidX Intellectual Property. It is deemed by the NDA to be Confidential Information whether it would be treated as such for the purposes of the equitable duty of confidence or not.

91. Details of the Business Opportunity (such as IX’s idea of creating such a fund, the rationale for it, and IX’s proposed structure of the proposed fund, including the use of a multi-cell strategy, provision for contributions to be made in kind and provisions for dealing with the inherent illiquidity of such a fund) were contained in a number of documents provided to the Defendants and which are pleaded in the Detail. These are the Canaima Capital Presentation, the 17 July slides, the AICF Presentation, the 12 August Fund Fact Sheet, the Canaima Fund Fact Sheet and the Claim Management Presentation (“the Fund Detail”). The Defendants accept that these documents are within the definition of Confidential Information for the purposes of the NDA (although they maintain that the information in them is in the public domain). Although these documents were fleshed out in the oral discussions between IX and the Defendants, those oral discussions are not pleaded or relied upon as Confidential Information save to the extent recorded in a document pleaded in the Detail such as the Due Diligence Note. The Defendants accept that the Due Diligence Note is within the definition of Confidential Information to the extent that it includes specific information.

Public domain

92. The Defendants’ case is that the Business Opportunity and all the information in the Detail was in the public domain. There is no definition of “public domain” in the NDA but the concept is well known to the law of confidentiality; see paragraph 124 of CF Partners above. Information is in the public domain if it “is so generally accessible that, in all the circumstances, it cannot be regarded as confidential”; per Lord Goff in Attorney-General v Observer Ltd [1990] 1 AC 109 at 282. Information may be known, or available to, a number of people but may still be “relatively secret”; see Franchi v Franchi [1967] RPC 149 at 152-3. Even if there is some loss of secrecy, there may still be value to the person owed a duty of confidence in preventing further access to the information. The person owed a duty of confidence may suffer loss or damage, or further loss or damage, if the information is published more widely. In such circumstances the information may remain confidential and subject to the duty of confidence.

93. The Defendants say that the NDA is impractical if public domain is not given a more restrictive meaning than it has in relation to the equitable duty of confidence in view of the wide meaning given by the NDA to Confidential Information. They say that the NDA should be construed so that information enters the public domain if it is provided to anyone not subject to a duty to treat it in confidence. I cannot see any force in that submission. If the definition of Confidential Information is wide that indicates (as a matter of objective construction) that the NDA was intended to protect more information rather than less. It would be contrary to that intention to impose an arbitrary construction of the words “public domain” to cut down the amount of information protected. The protection of more rather than less information may be restrictive for one or other of the parties to the agreement if they wish to use that information, but it does not make the NDA impractical. I reject the submission that giving public domain its usual meaning would deprive paragraph 1.1 (a) and (b) of any effect - as appears below and in the Schedule in relation to the Detail, there is plenty of continued effect in paragraph 1.1 (a) and (b). It seems to me that objectively construed, public domain is intended in the NDA to have the usual meaning the courts have given it in the context of the equitable duty of confidence.

94. It is correct that much of the information contained in the Detail could be obtained from public sources which were generally accessible. It is also correct that some information contained in the documents listed in the Detail was published by IX on its website. Information on its website was generally accessible. Some other information in the Detail was also published by IX in its newsletters which were sent to the 500 odd persons who had signed up for it. There was no selection of who received newsletters and they were not confidential. Anyone could have signed up for future newsletters. On the other hand, there is no evidence that the newsletters actually sent out were accessible to anyone beyond the investors who had signed up for them. It is a more nuanced question as to whether any particular information in the newsletters which were sent out was so generally accessible that it can be regarded as in the public domain.

95. The fact that Venezuelan debt was distressed, and that Venezuela had defaulted on most of its debt, was well known in the market. The fact that it could be traded notwithstanding the US sanctions was known among some specialist investors, but not widely known. The Business Opportunity - the opportunity to set up a sanctions compliant fund to exploit undervalued Venezuelan debt - was not widely known in the market. The Defendants say that the Business Opportunity was staggeringly basic, but I do not consider that it was. It seems to me that very few people knew that setting up a sanction compliant fund to trade in Venezuelan debt was possible. Even now, apart from ACOF and IX’s own post JV fund, the parties have only been able to identify one other fund which was established (the Copernico Recovery Fund).

96. The Defendants suggest that an article published in March 2019 by David Schneider (“Venezuela – an investment opportunity of a lifetime”) disclosed the Business Opportunity, but it does not do so. While identifying the potential for a substantial turnaround in Venezuela’s economic position if Nicolás Maduro left power, the focus of the article is on the long term potential of Venezuela’s future stock market if that were to happen. It mentions the opportunity for an expert investor to invest in sovereign bonds on the cheap in passing, while declaring that it was at that time “sheer impossible” to invest in any Venezuelan assets including bonds. Far from identifying the Business Opportunity it reinforces the fact that even amongst commentators on Venezuelan investments the opportunity to trade in Venezuelan sovereign debt was not widely known.

97. The Defendants also rely on an article by Clifford Chance (Venezuela - Navigating the Storm) from January 2018. The focus of the article is on existing creditors and their predicament, and in particular it considers the potential strategies they might have for restructuring or enforcement. That article explains the US and EU sanctions then in place, but by March 2019 these had been overtaken by further changes to the US sanctions regime. It outlines the many obstacles to be overcome in any restructuring of Venezuelan debt and in enforcing any judgment or award obtained by bondholders against Venezuela. It does not identify that bonds could be traded by non-US citizens. It does not identify Venezuelan bonds as an investment opportunity at all.

98. What these articles do is highlight how complicated and unclear the position was in 2018 and 2019 in relation to Venezuelan distressed debt. The Clifford Chance article describes Venezuela’s position as “politically and economically opaque” and “obscure”. Both articles explain the absence of reliable economic data from Venezuela. In my view they reinforce the conclusion that the Business Opportunity was not in the public domain.

99. The Business Opportunity itself was not published by IX or the Defendants as a collation of information except in the Fund Detail. It is right that much if not all of the information in the Fund Detail documents was publicly available and could be found if one looked; see for example the Clifford Chance article which mentions the fiscal agency structure of Venezuelan bonds and the collective action clauses in them, and the Torino “Venezuela Red Book” dated “H1 2019”, which contained detailed information about Venezuelan sovereign and PDVSA debt and their terms, and some information about US sanctions. However, the collation of that information to formulate a rationale for the idea of a sanctions compliant fund to invest in distressed Venezuelan debt was only available in the Fund Detail documents. The Defendants accept that the collation of information in each of the Fund Detail documents is Confidential Information for the purposes of the NDA.

100. The Defendants’ case is that the Canaima Capital Presentation, the AICF Presentation and the Canaima Fund Fact sheet (which on some of their documentation appears to embrace the 12 August Fund Fact Sheet) were marketing materials which were sent to investors and are therefore in the public domain for the purposes of Paragraph 1.1 of the NDA. The rest of the Fund Detail documents do not contain any significant information which was not in those marketing materials.

101. Prior to the JV, the Canaima Capital Presentation had been sent to potential investors by IX and an IX contact called Mr Ilardo. The precise number of investors to whom it was sent is not clear - Mr Moody-Stuart identified at least 17, but it was likely sent to more. It appears to have been intended to be circulated internally by the recipient to colleagues who might be interested, and to potential investors. However, this circulation was clearly intended to be treated as a confidential opportunity to serious potential investors. The presentation was marked “Strictly Private & Confidential”. It was not put on the website or circulated to IX’s newsletter database. It remained relatively secret because it was not circulated more widely. It was not intended to be, and was not, available to potential competitors to IX. So long as it did not fall into the hands of a competitor, the confidential information in the presentation retained its value to IX.

102. The AICF Presentation and the Canaima Fund Fact Sheet (possibly including the 12 August Fund Fact Sheet) were sent to about 200 potential investors by IX, Altana and Brevent for the purposes of the joint venture. The second slide of the AICF said it was “strictly confidential” and the Canaima Fund Fact Sheet was marked “private and confidential”. This was intended by IX, Altana and Brevent to be a confidential opportunity to be presented to serious potential investors. The presentation was not put on the website or sent to the wider newsletter circulation of IX or Altana. It remained relatively secret because it was not circulated more widely. It was not intended to be, and was not, available to potential competitors to IX. Mr Amore said that there was a general understanding in the industry that such teaser marketing was confidential - this was supported by Mr Kassin. The tenor of Mr Kastner and Mr Robinson’s evidence was that such a gentleman’s agreement existed but was not reliable and not honoured and it was therefore preferable not to disclose confidential information in such teaser marketing. They nevertheless both confirmed that they would not have wanted the teaser marketing to have been shown to a competitor and they would not have allowed it to be sent to a competitor. This shows that it was intended by them to be confidential and while a risk had to be taken that it would fall into the wrong hands, it was hoped that it would remain confidential. So long as these marketing materials did not fall into the hands of a competitor, the confidential information in the presentation retained its value.

103. I do not consider that sending these marketing materials to selected investors made them generally accessible to the public, or to other investors who did not receive them, or to competitors. In conclusion, neither the Business Opportunity nor the Fund Detail was in the public domain (or otherwise within the disclosure permitted by section 1.1 of the NDA).

Misuse

104. On the face of it there is clear misuse of the Business Opportunity and the Fund Detail. After the breakdown of the JV the Defendants simply carried on setting up the fund envisaged by the JV and called it the ACOF, to invest in the same assets as the AICF could have invested in and using the same corporate vehicle. They used the rationale for the AICF which was identified in the Fund Detail and the competitive edge given by knowledge of the need for protective proceedings which was also identified in the Fund Detail to market the ACOF. The ACOF implemented the strategy in relation to bonds identified in the Fund Detail and filed claims in New York in accordance with the IX confidential information about fiscal agency and prescription. Put simply, Altana and Brevent appropriated the Business Opportunity to themselves and exploited it.

105. I reject Mr Robinson’s evidence that he always had in mind the creation of a Venezuelan debt fund when the bond price was right.

i) There is no document disclosed by Altana in the 12 months prior to meeting IX in which there is any research or discussion of trading Venezuelan bonds at all, never mind setting up a fund to do so;

ii) The suggestion that Mr Robinson had done the research, was waiting for the price to hit 15, and kept this research and analysis entirely in his head, was highly implausible, contrary to his own evidence that he kept a written record of everything important, and contrary to the contemporaneous documentation where he presented the AICF as the trade of the decade in which he intended to invest at price points above 15;

iii) Mr Kastner accepted in evidence that he had very limited knowledge about Venezuelan debt prior to March 2019 and the contemporaneous documents of communications between Mr Kastner and Mr Robinson make no reference (as one would have expected) to any plan harboured by Mr Robinson to launch such a fund when Mr Kastner brought the IX idea to him. Nor did Mr Kastner give evidence that he had been told by Mr Robinson of such a plan. Mr Kastner now receives what he describes as “a meaningful share” of Altana’s fees from the ACOF fund, and as the contemporaneous documents show, at least part of which is for introducing Mr Robinson to the opportunity by introducing him to IX; see the email chain between Mr Kastner and Mr Robinson on 4 June 2019 and 9 to 11 July 2019. It is inconceivable that Mr Robinson would have paid Mr Kastner an introducer’s fee for introducing an opportunity he had already identified.

iv) As I have already observed the transcript of the first call with Mr Amore shows Mr Robinson was a novice in relation to Venezuelan debt. Mr Robinson is recorded in the contemporaneous documents as referring to the idea as Mr Amore’s idea and to having been educated by Mr Amore; see e.g. the Mercantil call transcript. Mr Robinson and Mr Kastner agreed at an early stage of the joint venture that they needed IX more than IX needed them (and I reject the suggestion that this was solely a reference to the claims which IX could source - see below).

106. I am satisfied that prior to their contact with IX neither Mr Robinson nor Mr Kastner were aware of the ability to create a sanction compliant fund to trade in distressed Venezuelan debt. This reinforces the point that this was not information in the public domain if someone of Mr Robinson’s expertise was not aware of it. It also confirms that they took the idea from IX, as there are no other alternative sources for that idea.

107. I reject Mr Robinson and Mr Kastner’s evidence that there was a different investment thesis behind the ACOF because the AICF was intended to focus on claims and the ACOF intended to focus on bonds. The IX proposal was, from the outset, a fund which was intended to invest in bonds as well as claims.

i) That was apparent from the Canaima Capital Presentation, the definition of Opportunities in the NDA, the 17 July Slides, the AICF Presentation, the Canaima Fund Fact sheet and various emails from Mr Robinson and Mr Kastner.

ii) The transcript of the first conversation between Mr Amore and Mr Kastner on 18 April 2019 shows Mr Amore was pitching the idea that it was attractive to buy bonds as well as claims.

iii) The Pictet experiment in July 2019 (see paragraph [44] above) shows that bonds were a significant part of the JV’s focus.

iv) By August 2019 bonds were trading at 15 - 20%. Mr Robinson and Mr Kastner considered bonds to be attractive at this level and said so in emails to investors, emails which made no mention at all of claims.

v) The AICF Presentation and the Canaima Fund Fact sheet which was sent to potential investors in July, August and September 2019 showed a proposed allocation of 50% to sovereign and PDVSA bonds.

vi) Mr Robinson said to Mercantil in the Mercantil Call on 28 October 2019, “we set this up originally from an idea by Celestino to take advantage of what we think are incredibly cheap assets in Venezuelan bonds and PDVSA bonds…”

As the March ACOF Marketing email shows the ACOF is the fund which was envisaged by the JV partners in the summer of 2019. The ACOF has essentially the same range of investable assets as the AICF. It happens to have only invested in bonds as, due to price falls since the start of the joint venture, the relative value of bonds makes them more attractive than other asset types. This is not a different investment thesis to the AICF. Had the AICF been set up it would doubtless have done the same. The thesis of both was to invest in Venezuelan distressed debt as “the trade of the decade”.

Trade Secrets

108. Regulation 2 of the Regulations defines a trade secret as “information which –

“(a) is secret in the sense that it is not, as a body or in the precise configuration and assembly of its components, generally known among, or readily accessible to, persons within the circles that normally deal with the kind of information in question,

(b) has commercial value because it is secret, and has been subject to reasonable steps under the circumstances,

(c) by the person lawfully in control of the information, to keep it secret;”

109. IX says that the Business Opportunity was a trade secret and seeks to have damages formulated in accordance with Regulation 17 of the Regulations.

110. Infringement under the Trade Secrets Regulation is expressly defined in r 3(1) by reference to breach of confidence in confidential information, as follows:

“(1) The acquisition, use or disclosure of a trade secret is unlawful where the acquisition, use or disclosure constitutes a breach of confidence in confidential information.”

111. From the perspective of infringement, IX’s claim under the Trade Secrets Regulation stands or falls with its claim in misuse of confidential information in respect of the Business Opportunity. As IX has succeeded on that issue it has succeeded on establishing an infringement of the Trade Secrets Regulation.