Mr Recorder Douglas Campbell

QC:

Introduction

1.

This is a case about a range of retro-style motor scooters based on the

well-known Lambretta scooters of the 1960s. The Claimants’ range is sold under

the marque Scomadi. The dispute is about 3 different scooter models, each of

which is made in China by the additional counterclaimant (“Hanway”) and which

D3 wishes to distribute in the UK. These 3 models are generally referred to as

the Royal Alloy scooters, but more particularly are the GT, the GP mark I

(“GP1), and the GP mark II (“GP2”).

2.

The background is that the Claimants came up with the idea of

re-launching updated versions of the classic Lambretta scooters, and entered

into two agreements with Hanway (referred to as the Design and Manufacture

Agreement, and the Supplementary Agreement) relating to the production thereof.

This relationship later broke down, and resulted in the present litigation.

3.

The parties to the present litigation fall into two groups. I will

refer generally to the Claimants (ie the two Scomadi companies, which are in

the same control and ownership) as “the Claimants”, and to the Defendants to

the original action plus Hanway as being “the Defendants” for ease of reference

save where it is necessary to distinguish between them (as it is, for instance,

in relation to the contractual claims).

4.

These proceedings are complicated by a wide range of claims and

counterclaims covering breach of contract, trade mark infringement, passing

off, Registered Community Design (“RCD”) infringement, UK unregistered design

right infringement, negligent misrepresentation, negligent misstatement,

infringement of copyright, and rescission . As a result of various case

management orders made on previous occasions, notably the order of Morgan J

removing unregistered design right issues relating to the GP1 and GP2 scooters

from the trial; and the cooperation of the parties, including the Defendants’

acceptance that the GT infringes some of C1’s unregistered design rights, the list

of issues for trial reduced to the following.

The Supplementary Agreement

1) Was

the Supplementary Agreement (“SA”) a legally-enforceable binding contract

between Hanway and the First Claimant? In particular:

a) Was

the SA drafted without prior input from the Claimants and presented to them for

signature without prior notice?

b) Is

consideration for the SA found in (i) the compromise of arguable claims for

breach of contract, negligent misrepresentation and/or negligent misstatement

or rescission (ii) the continuation of the venture between Hanway and the First

Claimant (iii) the variation of the commercial terms of the Design and

Manufacture Agreement (“DMA”), or (iv) Hanway’s agreement not to assert

arguable rights against the first Claimant?

2) Are

the Claimants estopped from asserting that the SA is of no contractual effect?

3) Is

the Defendants’ trade in the Royal Alloy Scooters permitted pursuant to the SA

(without prejudice to any issues relating to passing off and/or trade mark

infringement)? In particular:

a) What

is the correct interpretation of the SA?

b) What

is the correct interpretation of the DMA?

c) When

did the Claimants first “find” a third party to produce the scooters in issue?

d) In

what circumstances was the DMA terminated?

The Claimants’ design rights

4) Are

the RCDs novel and do they have individual character?

5) Are

any of the features of the RCDs solely dictated by technical function?

6) Do

the Royal Alloy Scooters or either of them produce on the informed user a

different overall impression to the RCDs or any of them?

7) Are

the Defendants or any of them liable for infringement of the RCDs or any of

them?

8) Are

the Defendants or any of them liable as joint tortfeasors for acts of

infringement of the other Defendants?

Relief

9) Are

the Defendants entitled to declarations that each of the Royal Alloy scooters

does not infringe the RCDs or any of them?

5.

Most of the hearing was taken up with issue 3, and in particular issue

3(a).

The witnesses

6.

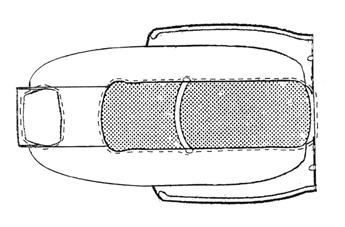

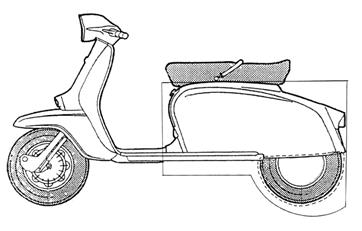

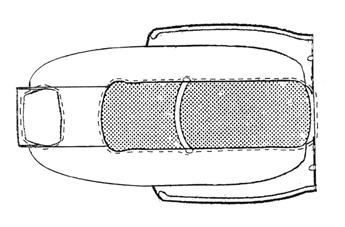

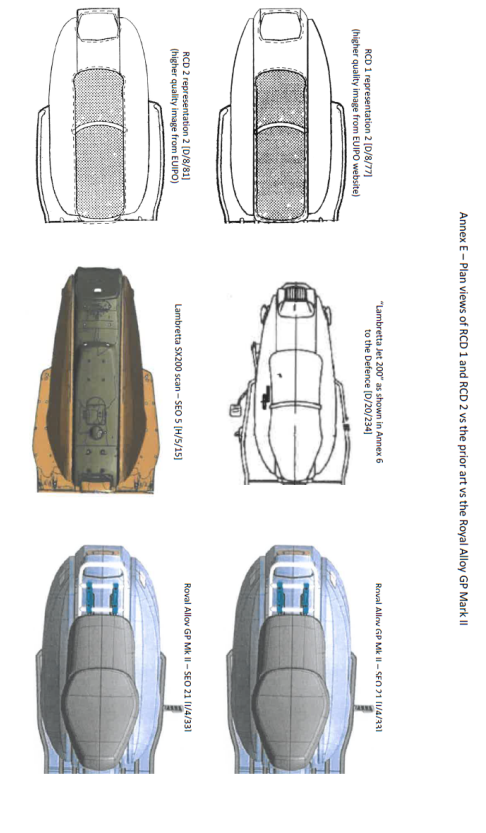

On behalf of the Claimant I heard oral evidence from Frank Sanderson, a Director

of both Claimants; and Mr Paul (Paulino) Melici, also a Director of both Claimants.

On behalf of the Defendants I heard oral evidence from Mr Yiming Chen, the Second

Defendant; and Mr Oliver, General Manager of the Third Defendant.

7.

Both side’s counsel described Mr Sanderson as combative, and I agree.

The Defendants’ counsel also submitted that Mr Sanderson was evasive. There is

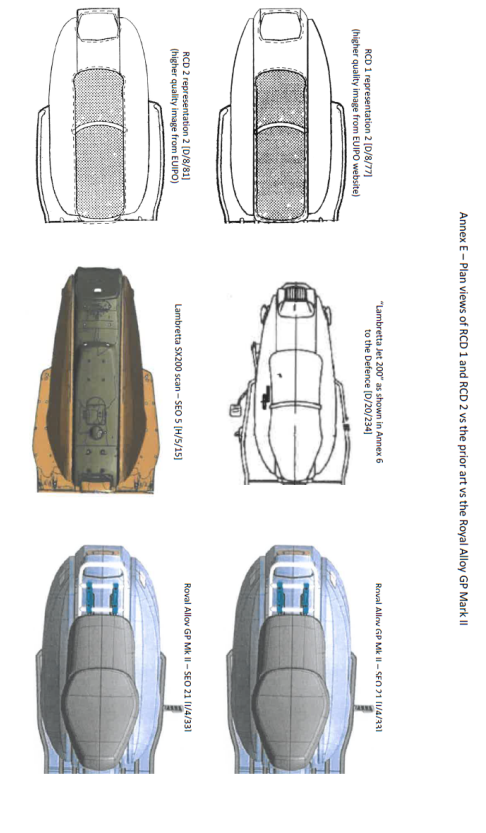

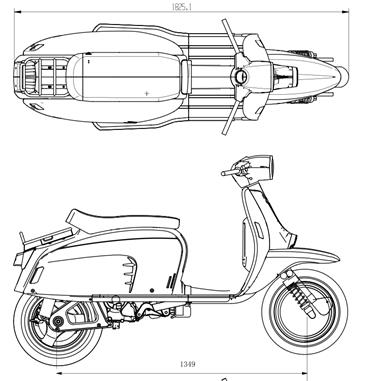

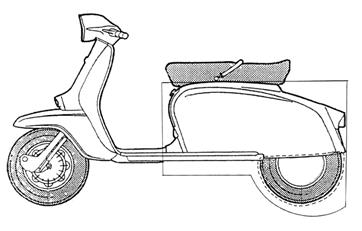

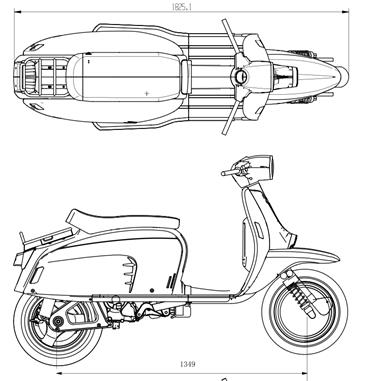

substance in this criticism too, particularly as regards Mr Sanderson’s dealings

with Mr Pimol Srivikorn (referred to throughout the trial as “Pimol”), a Thai businessman

interested in the scooter sector. I shall explain the significance of these

dealings with Pimol below.

8.

The Defendants requested that Mr Melici should wait outside Court whilst

Mr Sanderson was being cross-examined, and the Claimants agreed to this

course. In the result Mr Melici’s oral evidence covered much less ground than

that of Mr Sanderson. He gave his evidence clearly. The Defendants did not

criticise his evidence, nor did they allege any inconsistency with that given

by Mr Sanderson.

9.

Mr Oliver’s evidence was criticised by the Claimants as being

unconvincing as regards the circumstances in which the Third Defendant and

Hanway began dealing in the Defendants’ scooters. I reject this criticism.

This topic was only peripheral to the issues in any event.

10.

Mr Chen gave his evidence through an interpreter. I have made

allowances for this. When speaking about the work Hanway had done, his

evidence was clear and consistent.

11.

Another part of Mr Chen’s evidence was his attempt to explain why Hanway

had applied for (a) a community registered design, and (b) a large number of “Scomadi”

trade marks in its own name in a large number of jurisdictions, all without

telling the Claimants. He said that so far as the design was concerned he was

simply testing the Community design registration system to see if what he thought

was an invalid registration could be registered; that so far as the Scomadi

trade marks were concerned he thought the Claimants’ rights to their own name

only applied in Europe; and that he did not tell the Claimants about any of

these applications because “I did not have a lot of contact with Scomadi

directly, and my employees would not be able to do that by themselves”. I

did not find this part of his evidence convincing.

12.

It is plain that this dispute has led to bitter feelings on both sides,

which have become entrenched by the process of litigation. The Claimants

submitted that in these circumstances I should primarily rely on the

contemporaneous documentary evidence and inherent probabilities, with the recollection

of individual witnesses being tested against the same. I agree, and I shall do

so.

Issues 1-3 (contract)

13.

I will deal with the contract claim (ie issues 1-3) first. First I will

set out the law, which was not disputed, and then the facts, which were very

much disputed.

Legal context

14.

The legal approach to interpretation of contracts is well known. It was

recently and authoritatively explained by the Supreme Court in Wood v Capita

Insurance Services [2017] UKSC 24. In short the Court has to ascertain

what a reasonable person, that is a person who has all the background knowledge

which would reasonably have been available to the parties in the situation in

which they were at the time of the contract, would have understood the parties

to have meant: see Wood at [11], citing Lord Clarke in Rainy Sky v

Kookmin [2011] UKSC 50 at [21]. This is a unitary exercise, and proceeds

via an iterative process in which each suggested interpretation is checked

against the provisions of the contract and its commercial consequences are

investigated: see Wood at [12]. And where the contracts are not drafted

with the assistance of skilled professionals, the correct interpretation may be

achieved by a greater emphasis on the factual matrix as opposed to textual

analysis: see Wood at [13].

15.

The Claimants drew my attention to the contra proferentem rule,

as explained by Lord Mustill in the Privy Council in Tan Wing Chuen v Bank

of Credit and Commerce Hong Kong [1996] UKPC 2 BCLC 69, 77. The Claimants

described this rule (without dissent from the Defendants) as a tie-breaker in

cases of ambiguity.

16.

The Defendants relied on Sales J (as he then was) in Investec Bank

(Channel Islands) v The Retail Group plc [2009] EWHC 476 (Ch) for the

following proposition:

“76 Accordingly, in interpreting a

contract, regard may be had to the content of the parties' negotiations to

establish “the genesis and object” of a provision. This seems to me to be a

relevant part of the factual matrix, since if the parties in the course of

their negotiations are agreed on a general objective which is to be achieved by

inclusion of a provision in their contract, that objective would naturally

inform the way in which a reasonable person in the position of the parties

would approach the task of interpreting the provision in question…”

17.

The Defendants also relied on Peekay Intermark v Australia and New

Zealand Banking Group [2006] EWCA Civ 386 as to the effect of statements in

the contract itself as to the basis thereof. In that case Moore-Bick LJ (with

whom Chadwick LJ and Lawrence Collins J agreed) held as follows:

“56. There is no

reason in principle why parties to a contract should not agree that a certain

state of affairs should form the basis for the transaction, whether it be the

case or not. For example, it may be desirable to settle a disagreement as to an

existing state of affairs in order to establish a clear basis for the contract

itself and its subsequent performance. Where parties express an agreement of

that kind in a contractual document neither can subsequently deny the existence

of the facts and matters upon which they have agreed, at least so far as

concerns those aspects of their relationship to which the agreement was

directed. The contract itself gives rise to an estoppel: see Colchester Borough

Council v Smith [1991] Ch. 448, affirmed on appeal [1992] Ch.421.”

The Claimants did not dispute this principle.

18.

There was a dispute about whether there was any consideration for the

SA, but there was no dispute about the relevant law. I can summarise it as follows:

i)

It is no consideration to refrain from a course of action which it was

never intended to pursue: see Arnale v Costain Civil Engineering [1976]

1 Lloyd’s Rep 98, 106.

ii)

Even where the new contract between A and B involves performing

existing contractual obligations which A owes to B, there can still be

consideration, In particular this can arise where B has some reason to doubt

whether A will complete his side of the bargain, B promises A an additional

payment, and as a result of giving his promise B “obtains in practice a

benefit, or obviates a disbenefit”. See Williams v Roffey [1990] 2 WLR 1153, CA.

iii)

Where the parties agree to vary a contract in a way that can prejudice

or benefit either party, the possible detriment or benefit suffices to provide

consideration for the promise of either party. The possibility itself is

sufficient. Thus if there is an agreement to vary the currency in which

payments are made, it is immaterial that there is in fact no benefit (because

the new currency depreciates) or that it was highly probable at the time of

variation that the new currency would so depreciate. See Chitty, 32nd

edition, at 4-080 citing various authorities.

19.

The Claimants reminded me that at common law a party can treat itself as

discharged from its obligations under a contract if the other party is in

repudiatory breach: see Stocznia Gdynia v Gearbulk [2009] EWCA Civ 75.

The facts

The parties’ dealings leading up

to the DMA

20.

The Claimants originally approached Hanway at a trade show called the

EICMA show in Milan in 2011. This is an annual motorcycle show which has been

running for over 100 years. The introduction was made via the European

distributor of the Claimants’ products, a Dutchman called Mr Robert Olsthoorn.

21.

The Claimants decided that in general they would not send Hanway CAD

drawings of their designs before entering into any firm agreement. The only

exception to that consisted of some sample STP drawings, a type of CAD

drawing. (Mr Chen explained that STP files are the type of files that are usually

used to “open” moulds, ie to produce moulds that will then be used for

production). Mr Sanderson sent these drawings to Hanway by email on 26th

February 2012. He explained that he did so to show Hanway that the Claimants

were in good faith and had done CAD work, but that the specific drawings which he

sent were not particularly important because they could not have been used to

build a vehicle.

The DMA

22.

The First Claimant then entered into a Design and Manufacture Agreement

(“the DMA”) with Hanway on 13 March 2012. It contained provisions for royalty

payment (see clause 3) weekly written production reports by email (see clause 5),

and the following provision re intellectual property rights:

“7.1 All

intellectual property rights and new material (including but not limited to

copyright and design rights) therein in them shall be and remain the sole

property of [the First Claimant]”.

The DMA did not define what it meant by “intellectual

property rights”.

23.

The First Claimant also had the right to terminate the DMA by not less

than 30 days’ written notice to Hanway: see clause 8.1. Hanway had no contractual

right to terminate. The term of the contract was to expressed “to continue

from [date of signing] for the full production life of the scooter and

any or all derivatives”.

24.

It is common ground that despite its name the DMA did not impose any

obligations on Hanway either to design or to manufacture anything.

The parties’ dealings between the

DMA and the SA

25.

There are a number of disputes about how much work Hanway did between March

2012 and November 2013 in relation to preparing manufacturing drawings for the

scooters. I will summarise the evidence on this topic before reaching my

conclusion on it.

26.

First, Mr Sanderson accepted that Hanway did design some things. In his

second witness statement at [24], he specifically accepted that Hanway designed

the headlamp, indicators, and runner strips. Mr Melici also accepted that

Hanway did some design work.

27.

Secondly, the Claimants drew my attention to various disclosure

documents showing that Hanway spent about 3 to 4 months doing the work in

question. Hanway did not start in earnest until in or after April 2013 and the

work was largely complete by August 2013. The Claimants did not take me

through the detail of the work in question, but this is not self-evidently a

trivial amount of time. Mr Chen said that this process would normally “take

up to 2 months or 3 months maximum”.

28.

Thirdly, the Defendants relied on an email which was later sent by a

Hanway employee by the name of Elvis Lv on 15 September 2015. This email had

been prompted by a perceived slight on Hanway’s work by the Claimants. In it

Mr Lv claimed that Hanway had been “leading the way in research and

development for Scomadi project since the beginning” and claimed that

Hanway had designed a large number of features including all plastic body

parts, hubs, main cables, front/rear lamps, speedometer, front/rear braking

systems, and an engine bracket bush, as well as finding new engines.

29.

The Claimants’ response to this email at the time was conciliatory, and did

not dispute Mr Lv’s allegations about what Hanway has designed. However in

their evidence to me both Mr Sanderson and Mr Melici made it clear that they

did not accept the substance of what Mr Lv had said, and gave reasons. I do

not think it is safe to place much reliance on this email.

30.

Fourthly, Mr Chen produced various exhibits illustrating design work

which he claimed Hanway had done: see his exhibits YC5 to YC7. It was not put

to him that there was anything incorrect about these exhibits. The Claimants’

case was instead that these exhibits only showed that Hanway had done a limited

amount of design work. Mr Sanderson was dismissive of Hanway’s design

contribution generally, calling it mere “productionisation”. In his view this was

not enough to create any rights. Mr Chen disputed Mr Sanderson’s evidence on

this topic. He explained that the CAD drawings done by the Claimants largely

focussed on the outside of individual panels, or how they connected together. Mr

Chen was not challenged on this.

31.

I do not agree that it is fair to dismiss Hanway’s work as trivial in

design terms just because it is “productionisation”. The whole reason why the

First Claimant approached Hanway in the first place was in order to turn its

CAD drawings into designs for production-ready moulds. One would not expect

these detailed changes to have a major effect on the overall visual appearance

of the original design. However it does not follow that Hanway’s design contribution

must have been trivial or unimportant. This was because Hanway’s design changes

were intended to implement the designs shown in the CAD drawings, as opposed to

modifying them. In particular these design changes were intended to make each

and every part of the scooter fit together in a way which was suitable for mass

production, as Mr Chen explained. In short Hanway started off with CAD

drawings which could not be used for manufacturing purposes and used them to

create designs which could be so used.

32.

Mr Chen also claimed in his oral evidence that Hanway had done 80% of

the design work. This was not a figure he had mentioned before in any of his

witness statements. I accept that Mr Chen honestly believed this to be true,

but I do not think he was being objective about the 80% figure.

33.

Fifthly, there is no dispute that Hanway spent a substantial amount of

time and money – twice what they originally anticipated – making detailed

changes to the CAD designs in order to achieve that end result. This is apparent

from an email sent by Cathy Huang, then Sales Manager of Hanway, to Mr

Olsthoorn’s wife on 11th September 2013. Ms Huang explained that

when Hanway first saw a sample of the Claimants’ scooter (which was at a trade fair

in Cologne), Hanway estimated that it would cost less than 150 000 euros to

bring it to production, but that ”we now have invested more than $300 000 on

this project not including all the staff costs, and we didn’t save any cost

which is necessary for the model”. Ms Huang went on to propose that Mr

Olsthoorn contribute another $100 000 to Hanway’s costs. Mr Chen confirmed the

contents of this email in his oral evidence, and he was not challenged on any

of the statements made therein. Mr Sanderson also accepted that this email

showed that Hanway was unhappy about how much time and money they had to devote

to the project.

What was said at the 2013 EICMA show

in November 2013

34.

In paragraph 53 of his first witness statement, dated 25 August 2017, Mr

Chen explained that he raised the question of ownership of intellectual

property at the 2013 EICMA show. In particular Mr Chen said that because of

his (or rather Hanway’s) design input, he did not want the Claimants to be able

to take the scooter incorporating the Hanway designs to another manufacturer.

He said that both Mr Sanderson and Mr Melici readily agreed to this proposal.

35.

The other topic of discussion between the parties at the 2013 EICMA show

was the relevant royalty rate. In particular it was agreed that instead of 6%

(as per the DMA), it should be $35 in the future.

36.

Both Mr Sanderson and Mr Melici served witness statements in reply to

this statement, but neither of them took issue with Mr Chen’s paragraph 53. Indeed

Mr Sanderson’s second statement, at paragraph [26], confirmed that “Mr Chen

stated he had spent more on the project than expected … Mr Chen wanted a

greater involvement as he thought [he] had done more than OEM. This was the

genesis of the Supplementary Agreement”. When Mr Chen’s paragraph 53 was

put to him in cross-examination, Mr Sanderson agreed that Mr Chen’s desire to

prevent the Claimants taking the scooter incorporating the Hanway designs to

another manufacturer “may have been mentioned”.

37.

Nor was Mr Chen’s paragraph 53 effectively challenged in

cross-examination either. The Claimants merely put a single question to Mr

Chen that the only subject raised at the show was royalty payments, which Mr

Chen denied, and then left the whole topic at that. In their reply speech the

Claimants sought for the first time to argue that Mr Chen’s memory of this show

was at fault, but that was far too late to raise a point which should have been

put to Mr Chen in cross-examination.

38.

I accept Mr Chen’s evidence about what he said at this show. It is

consistent with the documentary evidence I have referred to above; there was no

evidence from the Claimants’ witnesses to the contrary; and it was not

substantially challenged in cross-examination.

Conclusion on extent of Hanway’s

design work

39.

I have found it difficult to quantify the precise extent of the design

work which Hanway which actually did in order to create the final production

designs. However that precise extent does not matter since I am in no doubt

that Hanway’s contribution to these final production designs was on any view

significant. I base this upon the evidence I have considered in paragraph

[26]-[38] above, excluding the Elvis Lv email and Mr Chen’s 80% figure. Mr

Sanderson did not agree that Hanway’s design contribution was significant, but

this was largely because of his view that “productionisation” could not create

any relevant rights and I have rejected that argument for the reasons set out

above.

The Supplementary Agreement (“SA”)

40.

Following the 2013 EICMA show, Ms Huang sent Mr Sanderson a draft of the

Supplementary Agreement (“the SA”) on 20 November 2013. It had only 2 points

in it. On 21 November 2013, Mr Sanderson replied by email raising an issue

about producing a “flagship version” of the scooter in Europe to qualify for

engine supply from Piaggio or other suppliers. He proposed a re-worded version

of the second point in order to deal with this possibility. The SA was then

signed between the First Claimant and Hanway on 25th November 2013.

41.

The construction of this document is disputed, so I will return to that

later. For the moment I will simply set out the relevant provisions, which are

as follows.

42.

The preamble to the SA states:

This

supplementary agreement clarifies two points based on previous agreement named

AGREEMENT FOR THE DESIGN AND MANUFACTURE OF A SCOOTER VEHICLE signed by both

Francis Henry Sanderson and Paul Melici on behalf of Scomadi Limited and chen yiming

on behalf of Changzhou Hanwei Vehicle Science and Technology Limited Company

43.

It then proceeds to set out the following:

POINT

1

Royalties

Rate Commission Payment Calculation

Payment

offered in US Dollars per scooter sold equals 35 USD for both 50cc and 125cc

instead of 6% as the original contract agree on. As for 300cc, Scomadi Limited

and Changzhou Hanwei Vehicle Science and Technology Limited Company will

consult for confirmation later.

Point

2

A.

As HANWAY have invested to develop the scomadi scooter project, and supplied

many good design ideas in the processes of developing the scooter, so HANWAY

owns some part of final design for frame, plastic parts and lamp moulds.

In

any case, two parties should consult and solve in a friendly way.

B.

However under no circumstance will Scomadi be allowed to find a third party to

produce the same or similar scooter. If this happens, HANWAY is not restricted

by any terms of the original contract and can sell this product to any market.

Even though Francis Henry Sanderson and Paul Melici own the design patent, if

Scomadi find a third party to produce this scooter, it will be treated as they

have agreed or confirmed that HANWAY can sell this scooter in any market.

C.

However Scomadi Ltd may complete the production of all 300cc piaggio engined

promotional scooters, and also be able to carry out themselves or contract out

if needed, the sub assembly production of the 250 cc and over, engined variants

until a time when Hanway can produce these models, without being in breach of

paragraph B above.

44.

The genesis of the SA is as follows. Parts A and B of point 2 come from

the original Hanway draft of 20th November 2013. Part C comes from

Mr Sanderson’s reply of 21st November 2013.

45.

Mr Sanderson explained in his second witness statement that “We were

concerned that the project would stall if we did not sign it”: see

paragraph [26]. See also his third statement, at [29]. In cross-examination

he confirmed this: “we thought that possibly if we did not agree to the [SA],

we might not get any production”. The SA itself does not actually contain

any terms requiring production, but that is a different matter. The point is

that the Claimants thought there might be no production at all if they did not

sign.

46.

Mr Chen said that if the SA had not been agreed, he would have pulled

out of the project. I am sure this is his genuinely held view today, after so

much litigation, but I am not sure that it would have been his view at the time

given the amount of money which he had already invested in it by then. However

I am sure that if the SA had not been agreed in the form in which it was

signed, Mr Chen would certainly have insisted on some sort of additional compensation

or security (eg increased down payments) from the Claimants before going into any

production. In such circumstances the project would have become significantly

more disadvantageous for the Claimants, to say nothing of delay. This is not an

unrealistic analysis since it seems to be much the same as the Claimants

themselves thought at the time.

The breakdown of the relationship

47.

The relationship continued into 2016. The scooters went into

production, so the First Claimant’s decision to sign the SA was duly rewarded.

Hanway paid the First Claimant a stream of royalties. Thereafter the

relationship started to deteriorate over time as a result of the Claimants’

dealings with Pimol.

48.

One can trace these dealings back to late 2015/early 2016, when Hanway

started to look for a joint venture partner in Thailand. Mr Chen, Mr

Sanderson, and Mr Melici all visited Thailand for this purpose in January 2016.

Thus far, they were all on the same side.

49.

Mr Sanderson’s written evidence was vague about the full extent of his subsequent

dealings with Pimol: see eg his second statement at paragraphs [33]-[37]. His

complaint was that “my company Scomadi has been caught in the crossfire of

two powerful Far Eastern businessmen with their own agendas in this matter”.

50.

The Claimants’ Supplementary Disclosure, which was provided by the Claimants

on 1 September 2017 (ie after witness statements were exchanged), told a

different story.

i)

On 11 May 2016, Pimol created a WhatsApp messaging group between

himself, Mr Sanderson, and Mr Melici, shortly after a meeting between the three

of them. This group did not include Mr Chen/Hanway, even though Mr Sanderson

claimed in cross-examination that his discussions and meetings with Pimol were

actually about Pimol’s joint venture with Mr Chen/Hanway.

ii)

Mr Sanderson also said in cross-examination that his discussions with

Pimol were about higher engine capacity models and “getting rid of quality

problems”. I disagree. Higher capacity models may have been part of the

discussion, but they were not the whole discussion. The rest of the discussion

was about replacing Hanway with Pimol. That is why Mr Chen was excluded.

iii)

On 9th August Mr Sanderson’s wife (who was also the company

secretary of the First Claimant) sent Pimol a draft manufacturing licence by

email. This was incomplete but Schedule 2 specifically referred, and only

referred, to scooters and motorcycles. By 31st August 2016 Mrs

Sanderson was exchanging emails with Pimol about corrections to distribution,

manufacturing, and supply agreements; and about the best way to structure the

arrangement between the parties in order to minimise tax liability with the UK

HMRC. I was not shown any documents which even mentioned higher capacity

models, let alone documents restricted to such.

iv)

By the end of September or the beginning of October 2016, these

distribution, manufacturing, and supply agreements appeared virtually complete,

although they were not signed until 1 February 2017. See Pimol’s email to Mrs

Sanderson dated 23 September 2016 and her reply attaching “three almost

complete draft agreements as requested” dated 1 October 2016. The only

substantive change thereafter seems to be insertion of company numbers: see Mrs

Sanderson’s email to Pimol dated 25 October 2016.

51.

Mr Chen did not know the full extent of the Claimants’ relationship with

Pimol at the time, but he had heard something about it from its Malaysian

distributor and he was concerned that the Claimants were for the first time having

their own stand at the EICMA show in November 2016. At that show, he spoke to

Mr Oliver who told Mr Chen that he had known since August that the Claimants

were setting up a factory in Thailand.

52.

Hanway then sent a letter to the First Claimant on 22nd

December 2016 in which Hanway purported to serve written notice of terminating

both the DMA and the SA on three months’ notice. The First Claimant’s

response, sent by Mrs Sanderson, was simply to express sorrow for the

communication and to ask about the situation as regards spare parts.

53.

On 9th January 2017, the First Claimant (acting via its

Chinese lawyers, Golden Gate), wrote to Hanway terminating the DMA and, inter

alia, demanding payments of all outstanding royalties. This letter did not

mention the SA.

Analysis

54.

I will deal with the issues in the order in which they have been set

out.

Issue 1(a) - was the SA drafted

without prior input from the Claimants and presented to them for signature

without prior notice?

55.

Although this was not formally conceded, I have found on the facts that

both sides contributed to the drafting of the SA.

Issue 1(b) - Is consideration for

the SA found in (i) the compromise of arguable claims for breach of contract,

negligent misrepresentation and/or negligent misstatement or rescission (ii)

the continuation of the venture between Hanway and the First Claimant (iii) the

variation of the commercial terms of the Design and Manufacture Agreement

(“DMA”), or (iv) Hanway’s agreement not to assert arguable rights against the

first Claimant?

56.

I find that there was consideration for the SA, as follows.

57.

First, in the continuation of the venture between Hanway and the First

Claimant. I have set out my findings on the evidence of Mr Sanderson and Mr

Chen: see [45]-[46]. In my judgment that is sufficient by way of a practical benefit

of the type identified in Williams v Roffey [1990] 2 WLR 1153, CA. The

fact that the SA did not itself require production is irrelevant.

58.

Secondly, the variation of the commercial terms; in particular, the

provision whereby the 6% royalty was replaced by a flat $35. Whether this was a

real benefit to the First Claimant depended on various factors, such as the overall

selling price, whether this change in royalty rates generated more sales, and

the Chinese yuan exchange rate. However the Claimants did not dispute the

Defendants’ argument that the possibility of an increased benefit was good

consideration: see above.

59.

The Defendants advanced other arguments, but it is not necessary to

consider any of them.

Issue 2 - Are the Claimants

estopped from asserting that the SA is of no contractual effect?

60.

The Claimants pointed out, correctly, that the Defendants’ pleading was

unclear in this respect. The Defendants’ response was that they only relied on

estoppel in the event that they lost the argument on consideration. Since I

have found for the Defendants on that issue, this does not arise either.

Issue 3 - Is the

Defendants’ trade in the Royal Alloy Scooters permitted pursuant to the SA

(without prejudice to any issues relating to passing off and/or trade mark

infringement)? In particular:

a) What

is the correct interpretation of the SA?

b) What

is the correct interpretation of the DMA?

c) When

did the Claimants first “find” a third party to produce the scooters in issue?

d) In

what circumstances was the DMA terminated?

61.

I will deal with issue 3(a) first. Both sides agreed that the SA was

not professionally drafted. There the agreement stopped.

62.

The Claimants argued that:

i)

The terms of the SA do not survive the ending of the DMA for Hanway’s

breach. This applied to any breach but applied a fortiori if Hanway was

in fundamental breach.

ii)

Even if the SA did apply, it did not permit manufacture of any further scooters

after the end of the DMA, but only permitted sale of scooters already

manufactured (ie a run-off period) in the end that the Claimants secured an

alternative manufacturer of the same or a similar scooter.

iii)

Their construction made commercial sense because it provided Hanway with

“further security for its investment” whilst preventing the Claimant

losing control “over the project to which its directors ... had devoted all

their lives”. This was so even without a runoff period, although if there

were a runoff period then this would protect Hanway against being saddled with

existing stocks.

63.

The Defendants argued that:

i)

The SA was specifically intended to apply in the very event that the joint

venture broke down. It was a “rough and ready resolution scheme”.

ii)

The SA was a complete code designed to reflect Hanway’s design

contribution, which contribution was expressly acknowledged in clause 2A. In

particular, Hanway was to become the exclusive manufacturer. If the Claimants

went elsewhere then Hanway itself was permitted to use the designs, subject to

an ongoing obligation to pay the $35 licence fee. Conversely the Claimants did

not have to pay Hanway anything. This remained the position whatever the

reasons for the breakdown.

iii)

The suggestion of a runoff period was inconsistent with the wording of

the clause. For instance clause 2B was triggered by the Claimant’s use of a

third party to produce “the same or similar scooter”, which meant that

Hanway was free to “sell this product”. The Defendants argued that this

wording went beyond what Hanway had actually manufactured, and was more apt to

reflect IP rights which were jointly owned and developed.

iv)

Their construction made commercial sense because the SA was in substance

a dispute resolution scheme whereby both parties who had contributed to the

design were able to run their separate businesses post-termination. Had it not

been for the SA, there would be “an unproductive and unsatisfactory

stand-off”.

64.

I accept the Defendants’ arguments, for the reasons given by the

Defendants. In my judgment the key point is Hanway’s contribution to, and thus

joint ownership of, the designs. I have found that there was such a

contribution as a matter of fact, so it is part of the background knowledge,

but in any event clause 2A acts as an estoppel against the First Claimant in

this respect: see Peekay. Once one accepts that both sides owned rights

in relation to the designs, and not just the First Claimant, then the rest of

the Defendants’ argument logically follows. The SA is indeed intended to apply

in the event that the First Claimant went elsewhere for manufacture of the

jointly owned designs, and it does provide a regime whereby both sides can

continue to manufacture scooters made to the relevant designs (or have such

scooters manufactured) as opposed to merely being able to stop the other doing

so.

65.

I agree with the Claimants that the Defendants’ construction leads to some

odd results. For instance, the Claimants would theoretically trigger the

operation of the SA by finding a manufacturer for a “similar” scooter which in

fact owed nothing to Hanway. The Claimants’ arguments about the distinctions

between different types of breach, and the proposed runoff period, also have

logic to them.

66.

However I agree with the Defendants that these arguments all amount to

rewriting the agreement (or a desire to do so) rather than interpreting it. The

main problem with these arguments, and the Claimants’ other arguments on

construction, is that the Claimants do not really address the consequences of

joint ownership of the designs.

67.

I also find that the SA operated as a variation of the DMA. Neither

party showed much enthusiasm for this argument, but it is obvious both from the

recitals and, insofar as relevant, from the circumstances relating to the SA.

68.

I turn to issue 3(b). The main argument between the parties on the

interpretation of the DMA was whether clause 7.1 prevented Hanway from applying

for design registrations and “Scomadi” trade marks in its own name. The short

answer to this is that clause 7.1 does not say so, but I will assume that it

does have this effect. I will deal with breach below.

69.

I turn to issue 3(c). Here there was a dispute as to what was meant by

“finding” a third party manufacturer. The significance of this is that such an

event gave Hanway a right to terminate the agreement between the parties

(ie the DMA as varied by the SA). This follows from the wording “under no

circumstance” and “Hanway is not restricted by any terms of the original

contract”, the latter being a reference to the DMA.

70.

“Finding” is an ordinary English word but the question is what it would

be understood to mean in this context. One extreme view (for which neither

side argued) would be that “finding” covers the very first contact with a third

party manufacturer. The other extreme view (for which the Claimants contended)

is that “finding” requires concrete agreement with such a manufacturer. The

Defendants’ submission was that “finding” was triggered by an irrevocable

decision to use Pimol’s company and that this was satisfied at least by the end

of October 2016.

71.

In my judgment, the term “finding” in this context is not

restricted to entering into a formal contractual agreement as the Claimants

contend. I agree that it is satisfied by an irrevocable decision as the

Defendants submit, but in my judgment something less than an irrevocable

decision also suffices. As I have said, Mr Sanderson’s evidence on this topic

was evasive, but it is clear that at least by the end of October 2016 the First

Claimant had taken the commercial decision that it was going to proceed with

Pimol. In my judgment that commercial decision (whether or not it was strictly

irrevocable) amounted to “finding” a third party to produce the same or

similar scooter with respect to Pimol. Accordingly as at such date

Hanway was entitled to terminate the DMA/SA.

72.

As regards issue 3(d), the Claimants relied on various alleged breaches

of the DMA by Hanway. These were the applications for IP rights referred to

above, but also failures to report and/or make royalty payments, and finally

the purported letter of termination dated 22nd December 2016. The

Claimants said they were all fundamental breaches, particularly the last.

73.

I accept that the purported letter of termination could amount to fundamental

breach in circumstances where Hanway had no right to terminate. However, such

is not the position here. In my judgment Hanway was entitled to do just that.

The Claimants made a pleading point here, to the effect that the Defendants had

not specifically pleaded Hanway’s right to terminate, but the Claimants did not

allege that the pleading point prevented me from making the above finding, or

that the finding was not open to me on the evidence.

74.

I do not consider that the other alleged breaches by Hanway are

fundamental in nature. In my judgment they did not go to the heart of the

contract. Nor did the First Claimant allege they were repudiatory at the time.

Indeed the First Claimant did not even allege that the purported termination

was wrongful, let alone that it was a repudiatory breach. Given my finding

that Hanway was entitled to terminate when it did, these issues do not matter anyway.

75.

The way in which the issues are framed does not perhaps make it clear

that if the Defendants won on the contractual issues, the issue of RCD

infringement does not arise. Both parties nevertheless approached the case on

that basis, from which it follows that it is not strictly necessary for me to

consider the RCDs.

I will do so in any event.

Issues 4- 6 (Registered

Community Design)

76.

Again I will set out the law, then apply it to the facts. The RCD

registration numbers are 000245634-0001 (“RCD1”), 000245634-0002 (“RCD2”), and

001390454-0001 (“RCD3”).

Legal context

77.

It was common ground that Arnold J’s summary in Magmatic v PMS

International [2013] EWHC 1925 (Pat) of the correct legal approach to

assessing validity and infringement of registered community designs remains

good law notwithstanding that the actual finding of infringement was later

overturned by the Court of Appeal: see also Neptune (Europe) v Devol

Kitchens [2017] EWHC 2172 (Pat) at [145], Henry Carr J. This summary in

turn drew upon earlier authorities such as Samsung Electronics v Apple Inc

[2013] FSR 9, CA. I shall adopt that approach.

78.

I was also reminded of Dyson v Vax [2011] EWCA Civ 1206, Court of

Appeal, at [8]-[9], citing Jacob LJ in Procter & Gamble v Reckitt

Benckiser [2007] EWCA Civ 936:

3. The most important things in a case

about registered designs are:

(1) the registered

design;

(2) the accused

object; and

(3) the prior art.

And the most important thing about each of

these is what they look like. Of course parties and judges have to try to put into

words why they say a design has "individual character" or what the

"overall impression produced on an informed user" is. But "it

takes longer to say than to see" as I observed in Philips v

Remington [1998] RPC 283 at 318. And words themselves are often

insufficiently precise on their own.”

79.

It was accepted that the assessment should be conducted from all

perspectives that the informed user might realistically adopt: see Senz

Technologies v OHIM, cases T-22/13 and T-23/13, ECLI:EU:T:2015:310.

80.

In general the more design freedom, the greater the scope of protection

and vice versa: see Grupo Promer (T09/07), cited at first instance in

Dyson v Vax [2010] FSR 39 by Arnold J in a passage with which the Court of

Appeal agreed. The Claimants criticised that part of Arnold J’s judgment where

he had held that design freedom could be constrained by economic

considerations, citing Shenzhen Taiden v OHIM, case T-153/08 at [58]. I

do not agree with that criticism but nothing appeared to turn on this.

81.

Article 8 of the Designs Regulation (6/2002) provides that a Community

design “shall not subsist in features of appearance of a product which are

solely dictated by its technical function”. This is a narrow exception, as

is apparent from Lindner Recyclingtech GmbH v Franssons Verkstäder AB (R

690/2007-3) [2010] ECDR 1:

“As long as functionality is not the

only relevant factor, the design is in principle eligible for protection. It is

only when aesthetic considerations are completely irrelevant that the features

of the design are solely dictated by the need to achieve a technical solution”

82.

I was shown one of the Claimants’ own scooters (in particular a TL125) as

part of the Claimants’ case, but I do not rely on this since it is legally

irrelevant. It is the registration which counts in a registered design case. Nor

was any argument directed as to whether this scooter was made to any of the registered

designs, and if so then which.

Issue 4 - are the RCDs

novel and do they have individual character?

Analysis

83.

First, it is necessary to identify the informed user of the product in

which the RCDs are intended to be incorporated. There is no dispute that this

is a user of scooters.

84.

Secondly, it is necessary to identify the design corpus with which the

informed user(s) will be familiar. There was no detectable dispute here

either. The design corpus includes both classic Lambretta designs as well as

modern scooters.

85.

Thirdly, I have to compare the RCDs to the prior art, identifying

similarities and differences and assessing their respective overall impressions

having regard to the nature of the product, the design corpus and the

designer’s degree of freedom. I will deal with technical function separately

since the parties have identified that as a separate issue.

86.

By the time of closing submissions, it was conceded that RCD3,

registered as of 20 November 2013, was invalid by reason of some of the

Claimants’ marketing so I will not consider that further. I have reproduced RCD1

and 2, which both date from 2004, in Annex 1 to this judgment.

87.

It will also be noted that both registrations contain various additional

features, namely solid lines and dotted lines. As noted by the Supreme Court

in Magmatic, a key task for the Court is to interpret the design

registration at issue relying solely on the representations filed: see [2016] UKSC 12 at [30]-[35].

88.

In this case there was no real dispute about the effect of these lines.

If one starts with RCD1, the solid lines used in the first and third

representations indicate that the area for which protection is sought is not

the whole scooter, but the rear part of it excluding the seat. The second

representation then shows a top view of the part in question. The dotted lines

exclude areas for which protection is not sought, such as the rear light, the

rear wheel and the seat. The same conclusions follow for RCD2, for the same

reasons. The relevant area was described at trial as consisting of central

part, side panels, plus footplate.

89.

The overall impression conveyed by these designs is difficult to put

into words. The Claimants referred to a “flatter, more bulbous main body”.

This is not just general but seeks to defines the registered designs by

comparison to something else which is not identified. The Defendant said there

were only 3 principal features in the plan views, namely the footplate, the

width of the rear body, and the shape of the profile of the rear body, and made

detailed submissions about each of these features. This is as specific as the

Claimant’s formulation is general. In my judgment the correct formulation is

somewhere between the two, as follows.

90.

RCD1 shows the rear end of a classic Lambretta scooter having a body

section and a footplate. When viewed from above, it has side panels which

extend noticeably outwards from the seat by and which taper gradually towards

the rear and a footplate which extends beyond the side panels by a constant

distance except at the very front. Overall, it would be seen by the informed

user as a variation on the classic Lambretta scooter theme, where the variation

lies in the details mentioned.

91.

RCD2 also shows the rear end of a classic Lambretta scooter having a

body section and a footplate. When viewed from above, it has side panels which

extend noticeably outwards from the seat and a footplate which extends beyond

the side panels by a constant distance except at the very front. The side

panels extend all the way out from the rear light and the side panel profile is

sharply curved towards the ends, so they look a little like a hamburger bun.

Overall, it would be seen by the informed user as another variation on the

classic Lambretta scooter theme, where the variation again lies in the details

mentioned.

92.

The above analysis focusses on the views from above because the Claimants

relied particularly on the width (which is most visible in plan view) in order

to establish validity. The plan view is only 1 view, but I agree that it is

important to the informed user. For instance it is the view that the user will

have when riding the scooter, when approaching it, and when getting on and off.

There was no detailed argument directed to the side view, probably because of

the prior art.

93.

I now turn to the prior art. There were a number of citations, but

those relied upon in closing were the Lambretta Jet 200 and Lambretta SX200,

and in particular the plan views thereof. The Defendants produced a comparison

of the RCDs, this prior art, and two of the alleged infringements (the GP1 and

GP2) and I reproduce this comparison in Annex 2. The Defendants did not

produce any 3-way comparison in relation to the GT, or indeed any overhead

views of the GT at all, but the Claimants did produce an overhead view of the

GT and I show this in Annex 3.

94.

Again there are only 3 principal features visible in the prior art plan

views. In relation to the Lambretta Jet 200 I find as follows:

i)

The rear body is again wider than the seat alone, but the length:width ratio

is visibly different to that in either RCD1 or RCD2. The Defendants did some

fairly unscientific measurements with a ruler which produced a ratio of 2.74,

compared to 2.13 for RCD1 and 2.14 for RCD2. The Claimants did not do any

measurements at all and gave no figure for the aspect ratio. However the point

here is not so much the absolute value (and certainly not to 2 decimal places) but

the visible nature of the difference.

ii)

The profile of the rear body is similar to that of RCD1: see above.

iii)

There is a footplate which extends beyond the rear body and runs about

half way along it, but it has a different profile to either RCD1 or 2.

Specifically it is wider at the front and tapers at the back.

The

overall impression of the Jet 200 is thus that is another variation on the rear

end of a classic Lambretta design generally, this time having these detailed

features.

95.

In relation to the Lambretta SX200 I find as follows:

i)

The rear body is again wider than the seat alone, but again it is a visibly

flatter aspect ratio than either RCD1 or RCD2.

ii)

The profile of the rear body is notably asymmetric (more so than either

the Jet 200 or the RCD1) and angular. It looks more like a coffin than a hamburger.

iii)

There is a footplate which extends beyond the rear body and runs about

half way along it, but it has a different profile to RCD1 or 2. Specifically

it is wider at the front and narrower at the back. It is like the footplate in

the Jet 200.

Once again the overall

impression here is the rear end of a classic Lambretta design generally, this

time having these detailed features.

96.

From the above analysis it will already be apparent that the general

appearance of both RCDs is similar to the general appearance of the prior art,

and that the differences are minor in nature. In this case, considering the

design corpus generally makes little difference to the analysis since both of

the prior art designs specifically relied upon are already part of that design

corpus. In particular they are both classic Lambretta designs.

97.

So far as design freedom is concerned, the Claimants submitted that

there was plenty of design freedom since the designer was not obliged to take

styling cues from classic Lambretta designs. For instance the successor to the

Lambretta brand itself had taken a different design direction. I agree with

this as a principle, but the fact remains that the designers of RCD1 and RCD2

have taken very little advantage of this theoretical design freedom. On the

contrary they have produced something which only varies from the prior art in

details – in particular, in the details identified above. This is not

surprising since they were trying to produce something which closely resembled

the prior art.

98.

Drawing all of these points together, it seems to me that there are

enough detailed differences to support the validity of both RCD2 and RCD1 over

the pleaded prior art, in the sense that both of these designs are new and have

individual character having regard to the same. The major reason is the side

panels, with the footplate having less impact. This is more obvious in the case

of RCD2 since the profile of its side panels is noticeably different to that of

both the Jet 200 and the SX200. However in both cases the scope of the

monopoly conferred by registration is narrow and relies on detailed differences

with the prior art.

Issue 5 - are any of the features

of the RCDs solely dictated by technical function?

99.

This issue is formulated in the way it is because of the Defendants’

argument that the increased width of the rear of the scooters was due to a

technical desire to incorporate bigger engines. This, said the Defendants,

meant that each of the RCDs was invalid because of the provision whereby an RCD

cannot “subsist in features of appearance of a product which are solely dictated

by its technical function”: see Article 8 of the Regulation.

100.

I do not accept this argument. The mere fact that the design was

influenced by technical factors does not mean that aesthetic considerations are

completely irrelevant to the end result: see Lindner. Moreover these

scooters are consumer products, which are intended to have an appearance which

appeals to consumers. The side panels and foot plates are no exception.

101.

Consistently with this the Defendants’ witness on this topic, Mr Oliver,

expressly agreed that when designing the shape of the canopy, a whole range of

aesthetic considerations were taken into account. He also agreed that among

other things “you have to choose how you are going to curve it so it looks

pretty”. These admissions are fatal to this argument.

Issue 6 - Do the Royal

Alloy Scooters or either of them produce on the informed user a different

overall impression to the RCDs or any of them?

102.

This issue is expressed by reference to “either of” the Royal Alloy

Scooters but in fact there are 3 – the GT, the GP1, and the GP2. Both sides

approached the case on this basis. Once again the argument was dominated by

reference to the plan views.

103.

In relation to the GT I find as follows:

i)

The rear body is wider than the seat alone, but looks about the same

general width as both the RCD1 and RCD2.

ii)

The profile of the rear body is similar to that of RCD2 (ie the

hamburger).

iii)

There is a footplate which extends beyond the rear body and runs about

half way along it. The profile is like both of the prior art examples rather

than either the RCD1 or 2.

iv)

There are also rear indicators plus a metal rack. They are not features

(like the seat, wheel, and rear light) which are specifically excluded from the

scope of RCD1/RCD2; and the only reason for such specific exclusion must have

been because such features were thought to make a difference. However the user

is unlikely to attribute much significance to these items given their ubiquity

on scooters.

The overall

impression is that of another variant on a classic Lambretta design generally,

this time having these features.

104.

Is this a different overall impression to RCD1 or RCD2, taking the

design freedom and design corpus into account? In my judgment this is close to

the borderline so far as RCD2 is concerned. The difference in the footplate

profile is not so trivial it can be ignored entirely, and nor can the rear

indicators plus metal rack, but the similarity in the side panel size and

profile is more important in design terms. I conclude that the overall

impression on the informed user is not different, so the GT infringes RCD2. As

this shows, a narrow registration can still be infringed even by something

which is not identical.

105.

The side panels of the GT are quite different to those in the RCD1 design,

and the footplate is different too. This means that the overall impression on

the informed user is different, and RCD1 is not infringed by the GT.

106.

In relation to the GP1 I find as follows:

i)

The rear body is again wider than the seat alone. It looks like an

exaggerated version of the RCD1/RCD2 panels in this respect. The Defendants

calculated an aspect ratio of 1.88, although again the number is not important

save insofar as it confirms the general impression.

ii)

The profile of the rear body is different to either RCD1 or RCD2, since

it seems to have a gentle taper at the front although it does still have the

“hamburger” profile at the rear,

iii)

There is a footplate which extends beyond the rear body and runs about

half way along it. The profile is different to all of these seen thus far, but

is closer to the prior art than either the RCD1 or RCD2.

iv)

There are also other features visible in the plan view – eg the clear

rear indicators and the metal rack behind the seat. These are less important.

The overall

impression is that of the rear end of a classic Lambretta design generally,

this time having these features.

107.

Given the modest scope of protection conferred by both RCD1 and RCD2, and

the nature of the differences identified, the overall impression on the

informed user of the GP1 is different to both RCD1 and RCD2. Hence the GP1

does not infringe either design.

108.

In relation to the GP2 I find as follows:

i)

The rear body is again wider than the seat alone. It looks like the

GP1. The Defendants calculated an aspect ratio of 1.86, but this difference with

the GP1 is not particularly visible.

ii)

The profile of the rear body looks like that of the GP1, and has the

same differences with the RCD1/RCD2.

iii)

There is a footplate which extends beyond the rear body and runs about

half way along it. Its profile is like that in the GP1.

iv)

As with the GP1, there are also other features visible in the plan view

– eg the clear rear indicators and the metal rack behind the seat.

The overall impression is that

of the rear end of a classic Lambretta design generally, this time having these

features.

109.

Given the modest scope of protection conferred by both RCD1 and RCD2, and

the nature of the differences identified, the overall impression on the

informed user of the GP2 is different to both RCD1 and RCD2. Hence the GP2

does not infringe either design.

Issues 7-9

110.

These can be dealt with more briefly, having regard to the above.

Issue 7 Are the Defendants or any

of them liable for infringement of the RCDs or any of them?

111.

No, for the reasons given above.

Issue 8 Are the Defendants or any

of them liable as joint tortfeasors for acts of infringement of the other

Defendants?

113. This does not arise.

However it is clear on the evidence that all of the Defendants, and Hanway,

were jointly concerned in a plan to import and sell the scooters complained of

in at least the UK. The Defendants did not give any reasons as to why they

would not all be liable as joint tortfeasors if the products in question

infringed. I find that if I am wrong on infringement, the Defendants would all

be so liable.

Issue 9 Are the Defendants

entitled to declarations that each of the Royal Alloy scooters does not

infringe the RCDs or any of them?

113. The Claimants gave no

reason as to why the Defendants would not be so entitled, provided that I found

in the Defendants’ favour on infringement. Hence I am prepared in principle to

grant such declarations in relation to the GP1 and GP2. I will hear counsel on

the wording thereof.

Conclusion

112.

In short:

(a)

The Defendants are entitled to manufacture and sell all of the GT, GP1,

and GP2 pursuant to the true construction of the SA.

(b)

Both RCD1 and RCD2 are valid. RCD3 is invalid.

(c)

The GT infringes RCD2, but not RCD1. The GP1 and GP2 do not infringe either

RCD1 or RCD2.

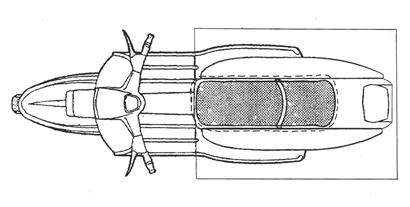

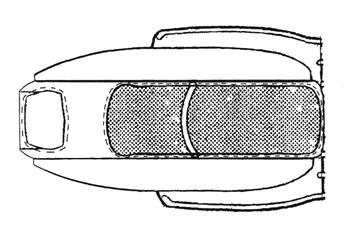

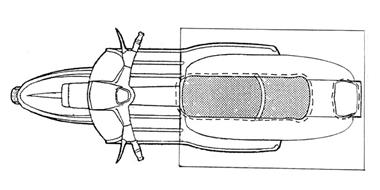

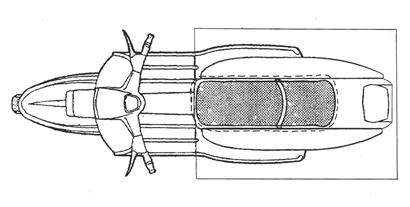

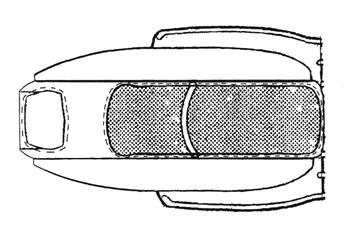

Annex 1 – RCD1

and RCD2 register entries

RCD1

0001.001

0001.002

0001.003

RCD2

0002.001

0002.002

0002.003

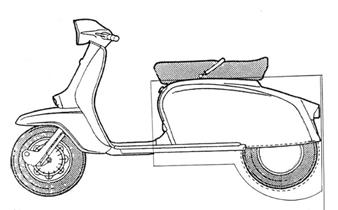

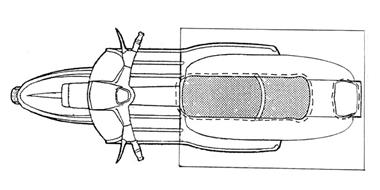

Annex 2

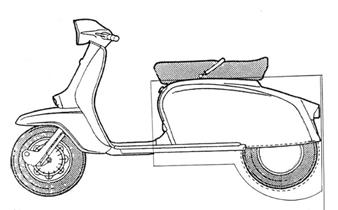

Annex 3

The GT