- This is an action for infringement of unregistered design right in the design of various items of clothing. The particular sector in issue is fast-fashion - where companies engage in releasing hundreds of different styles of low-cost garments per week, based on current trends found in social media.

- The Claimant, Sonia Edwards, began designing clothing in 2010. She mainly promoted herself through social media with the aim of licensing her designs to others. Her work at that time achieved recognition in Vogue Magazine and Drapers Magazine and was featured by The Fashion Network amongst others. She also exhibited at the Clothes Show Live in 2011 at the NEC in Birmingham. She has recently given up designing clothing, partly as a result of the present litigation.

- The Defendants are all part of boohoo, the well-known fast-fashion group.

- The proceedings have a long history, which I do not need to repeat here. Suffice to say, the Claimant has been complaining for a number of years about the alleged copying of her clothing designs by various big fashion brands, including ASOS, Missguided, Moschino and Shein. Ms. Edwards' complaints against boohoo have also been going on for some years.

- The matter has been case managed so that there were five designs before me (out of an original total of many more) to adjudicate upon at trial, with the issues being confined to liability only.

- At the trial, Ms. Edwards represented herself. It is a daunting exercise for a litigant-in-person to deal with multiple facts in a complex area of law in a compressed 2-day IPEC trial. Ms. Edwards acquitted herself admirably, both in cross-examination and in her opening and closing submissions.

- Andrew Norris KC and Becky Knott appeared for the Defendants instructed by Pannone Corporate LLP. Mr Norris performed the bulk of the advocacy but Ms. Knott addressed me clearly and concisely in closing on the issues of alleged copying and infringement. This was welcome and accords with recent guidance from the Lady Chief Justice and updated practice in the Patents Court.

- I am grateful to all the representatives for their cooperation in achieving an efficient and effective trial process. I thank in particular the Defendant's solicitors, Pannone Corporate LLP, for compiling the complex and voluminous bundles.

The Witnesses

- I heard from four live witnesses: the Claimant, Tom Kershaw, General Counsel and Company Secretary for the Boohoo Group PLC, James Blacklock, Chief Product Officer of the First Defendant, and Tom Binns, Chief Operating Officer of the Sixth Defendant. In my view all the witnesses gave their evidence fairly and truthfully. I comment below on their evidence in context, including on the witnesses who did not appear on behalf of the Defendants.

The Claim

- The Claimant's case is that she possesses unregistered design right in the shape and configuration of the following five garment designs:

i) Bikini top multiway ("Design 1");

ii) Organza rib puff sleeve high neck fitted top ("Design 2");

iii) High-waist gather to front and gather to back ruched skirt ("Design 3");

iv) High waist single gather ruched front skirt ("Design 4"); and,

v) High waist half ruched front leggings ("Design 5").

- Each of these designs, together with the Claimant's pleaded accompanying annotations, is represented at Annex 1 to this judgment. There is a considerable history to the pleading of these designs and the Claimant has had multiple attempts to define what she relies on. This has included the assistance of specialist intellectual property solicitors and counsel who were instructed at the time that the present pleadings were finalised. I was urged by the Defendants to constrain the Claimant to her pleaded case at trial, and given the history I consider it is fair to do so (albeit that no real attempt was made by the Claimant at trial to vary her case). There was a specific objection raised by the Defendants about the number of infringements alleged for each design. I return to this below.

The Law

- The legislation governing the subsistence of design right is contained in s.213 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 ("CPDA"), the relevant parts of which read as follows:

213 Design right.

(1) Design right is a property right which subsists in accordance with this Part in an original design.

(2) In this Part " design " means the design of the shape or configuration (whether internal or external) of the whole or part of an article.

(3) Design right does not subsist in—

(a) a method or principle of construction,

(b) features of shape or configuration of an article which—

(i) enable the article to be connected to, or placed in, around or against, another article so that either article may perform its function, or

(ii) are dependent upon the appearance of another article of which the article is intended by the designer to form an integral part, or

(c) surface decoration.

(4) A design is not " original " for the purposes of this Part if it is commonplace in a qualifying country in the design field in question at the time of its creation ; and "qualifying country" has the meaning given in section 217(3) .

- There are a couple of overarching points which I should make before turning to the detail of the individual designs. The Defendants criticise the way in which the designs are claimed by the Claimant. They point out that it is conventional for designs to be defined in proceedings such as this by reference to design documents with dimensions specified. Part of the exercise in assessing copying and infringement can then be carried out by comparing the dimensions of the claimed design with the alleged infringement.

- It is correct that this is the usual way in which design right claims are assessed. However, it is not a requirement for a design to have been recorded in a design document for design right to subsist. Design right can also come into being when an article is first made to the design (see s.216 CPDA). In the present case it was not the Claimant's practice to record her designs in design documents; instead the designs were made as articles. It is therefore legitimate for her to seek to define the designs by reference to contemporaneous pictures of the articles made.

- However, as a result of this, the designs are much more generally defined than they might have been had they instead been referenced in design documents. This has a number of consequences. First, it enables the Defendants to say that the claimed features are really descriptions of generalised concepts, rather than actual shape and configuration in the design. In Albert Packaging v Nampack [2011] FSR 32, Birss J quoted and then considered an earlier decision of Mann J in Rolawn v Turfmech [2008] RPC 27. He explained:

"19. In Rolawn Ltd v Turfmech Machinery Ltd [2008] EWHC 989 (Pat); [2008] RPC 27 , the claimant sought to protect not only the actual designs of its mower as it appeared in real life, but also aspects of that overall shape by reference to a more generalised level of abstraction. In rejecting this argument, Mann J. explained the following at [79] et seq:

"79. It is important to isolate the design in respect of which protection can be properly claimed, and it is vital to ensure that it falls within the definition of design. The Act defines design as ['any aspect of] the shape or configuration ... of the whole or any part of an article', and the right cannot exist until there is an embodiment of the design in an article or in a design document. This combination of features means that design right is confined to what one can actually see in an article—either the physical article or a drawing. This is what one would naturally expect from the concept of 'design' (which is what is protected) which is a physical manifestation of an idea, not some underlying abstraction, and it is reinforced by the definition of the 'designer' in s.214 as, 'the person who creates [the design]'. You cannot create a design until you have actually reduced it to a particular form. It is not a design while it is a conception in the designer's head, and it becomes a design when it takes physical shape on paper or in the flesh.

80. This means that Mr Alexander's more abstraction-based proposals for design right are not correct. His client is not entitled to claim design right in the abstraction of ideas involving folding over, folding again, and leaning on a stand and so on. Nor is it entitled to claim design right in the concept of a tank between two vertical support stands at the back of a wide-area mower. What it is entitled to claim design right in (subject, of course, to matters such as commonplace) is aspects or configuration of the physical manifestation, not some underlying design concept. ...

81. ...what is protected from copying in design right cases is the design, meaning the physical manifestation. It is not some underlying abstraction. The test for infringement is set out in s.226 ... if there is to be protection for the underlying ideas it must come through that, not because the underlying ideas are themselves the design. That, among other things, is probably one of the rationales behind the 'method or principle of construction' exception.

...

84. ... Rolawn are not, on any footing, entitled to claim design right in the concept of a mower which has arms folding back on themselves at the mid-way point. What they may be entitled to claim design right in is in their particular mower, or an aspect of the shape or configuration of it, one of which shapes can be verbally described in the manner just set out, but in which it is the actual manifestation of it which is the design."

20. As Mann J. explained, this is one of the policies behind the specific exclusion that says design right cannot subsist in a "method or principle of construction". This exclusion, and the "interface exclusion", in s.213 play an important part in the scheme of the 1988 Act by ensuring that design right provides a suitable amount of protection without unfairly restricting fair competition."

- A further related aspect which arises in relation to the design of clothes is whether they can be defined when being worn, or should only be described when off the body. This was discussed in Freddy SpA v Hugz Clothing Ltd [2020] EWHC 3032 (IPEC) by Deputy Judge David Stone. He rejected the claimant's attempt in that case to rely on the design of the goods as worn, holding as follows at §§96-99:

When Worn Design

96. There was what I might describe as a definitional objection which relates only to the When Worn Design. Put simply, the objection was that the shape of a pair of jeans "when worn" is not a protectable design, because it is a shape which is infinitely variable depending on the particular person wearing the jeans. Put another way, the Amended Defence claimed "the design is not the shape or configuration of an article as such, but the shape and configuration adopted by an article as produced where worn by a particular individual".

97. In response, Ms Rogan set out in her witness statement what the Claimant's counsel described as "a comprehensive explanation why the shape created by the WR.UP jeans is predictable". I accept Ms Rogan's explanation, as far as it goes. However, the difficulty I have is that the Amended Particulars of Claim aver that the shape the jeans take when worn "will necessarily be influenced by the body shape of the wearer". It is not enough to say that all wearers will have their buttocks both lifted and separated by the WR.UP jeans. I must assess the design as claimed. The Claimant itself avers that the shape of the jeans "when worn" will in part be determined by the shape of the wearer, and, even within a range of body shapes that would fit a given size of jeans, there will be a significant variation in body shapes. There was no evidence to say that the variously shaped wearers would all end up shaped the same when wearing the jeans. I accept Ms Rogan's evidence that the wearers' buttocks would be lifted and separated, but if those buttocks are of differing shapes, the resultant shapes of the jeans "when worn" will differ.

98. In his oral submissions, counsel for the Claimant put this slightly differently. He described the shape of the jeans when worn as "a lens through which one can, and in this case should, analyse the shape of the article itself". Counsel for the Claimant drew an analogy with a balloon, the rubber of which was of differing characteristics with different elasticities. When inflated, the balloon would not adopt a uniform shape. He said "when it is in its packet, it looks like a normal balloon, but when it is inflated, it adopts a fantastic shape of an animal. And the design that is ... assert[ed] is the shape of the product when it is inflated." I do not accept that his analogy is useful here. Air blown or pumped into a balloon will take the shape of the balloon, because the air within the balloon is at a consistent pressure throughout. A human body part inserted into a balloon will not take the shape of the balloon - rather, the balloon will take the shape of the body part.

99. I therefore accept the Defendants' pleaded case that the When Worn Design is invalid on the basis that, as pleaded, it does not constitute a protectable design.

- I accept and agree with this principle. A design right cannot vary depending on the individual who is wearing it. I therefore consider that I should discount from the designs in the present case any aspects which are materially influenced by the shape of the individual wearing them.

- Reflecting Albert Packaging and Rowlawn, Deputy Judge Stone also observed at §107 that the "method or principle of construction" objection is liable to be applied to descriptions of design which are abstract and "are expressed too broadly beyond a claim to shape and/or configuration".

- I need to bear all these factors in mind as I assess each of the designs. The knock-on effect of a more generalised description (i.e. without dimensions) is that it ought to be easier to allege that the design is a method or principle of construction or is "commonplace", because the generalised concept is more likely to have been seen before. To the extent the design is still valid, the broader definition may also make it easier to establish that the alleged infringements are articles made "exactly or substantially to that design" (s.226 CPDA 1988). However, demonstrating copying may be more difficult because there are likely to be other sources from which the alleged infringing design has been derived. Further, tell-tale indications of copying (e.g. repetition of precise dimensions) are less likely to be present.

- At the same time it is necessary to remember the fundamental principle of the law of copyright and designs that protection is given not to ideas, but only to the expression of those ideas. The more generalised the description of the work, the further it gets from expression towards idea. This boundary must be carefully guarded.

- In the present case the Defendants did not advance any case at trial that the designs are commonplace. Mr Norris explained to me that this was because of the high hurdle required to show that. That may be, but it means that one of the checks against asserting a more general design is not present. I will have to deal with the case accordingly.

- The other general point to make is that up until 2014, unregistered design right could subsist in "any aspect of" the shape and configuration of the whole or part of an article. But the CPDA was amended in 2014 by s.1 of the Intellectual Property Act 2014 to delete the words "any aspect of" from the definition of a design. This narrowed the definition of a design.

- The effect of this amendment has been to limit protection to designs of the whole or part of the article and prevents claimants from cherry picking certain features from a design and "claiming disembodied features, arbitrarily selected". See Henry Carr J. in Neptune (Europe) Ltd v Devol Kitchens Ltd [2017] F.S.R. 3 at §33. Here the claimant had relied on selected features from the design of a kitchen cabinet and not relied on other features of the same cabinet. Henry Carr J. continued:

"44. This raises the subtle question of the difference between "parts" and "aspects" of a design. In my view, aspects of a design include disembodied features which are merely recognisable or discernible, whereas parts of a design are concrete parts, which can be identified as such. Returning to the example of Laddie J in Ocular Sciences, aspects of the design of a teapot could include the combination of the end portion of the spout and the top portion of the lid, which are disembodied from each other and from the spout and lid. They are not parts of the design."

- Henry Carr J. also held that the amended definition applies to designs whether they were created before or after the amendment, if the alleged infringement occurred after the date of the amendment (Neptune, §42). That is the position in the present case and I have no reason to depart from this reasoning.

- Finally, as to what is necessary for a design to be "original", I was referred to Infopaq International A/S v Danske Dagblades Forening (C-5/08) EU:C:2009:465 [2012] Bus LR 102. According to this the design must be the expression of the author's own intellectual creation. This standard was recently confirmed by Arnold LJ in THJ Systems v Sheridan [2023] EWCA Civ 1354. He explained that the standard is met where the author was able to express their creative abilities in the production of the work by making free and creative choices so as to stamp the work created with their personal touch. In contrast, the criterion is not satisfied where the content of the work is dictated by technical considerations, rules or other constraints which leave no room for creative freedom. See §16 and the case law referred to therein.

- As a matter of principle I consider that a designer of garments is generally likely to need to use their intellectual creation to create a design. Subject to the individual circumstances there is therefore no reason why design right should not subsist in clothing designs - as in Freddy v Hugz.

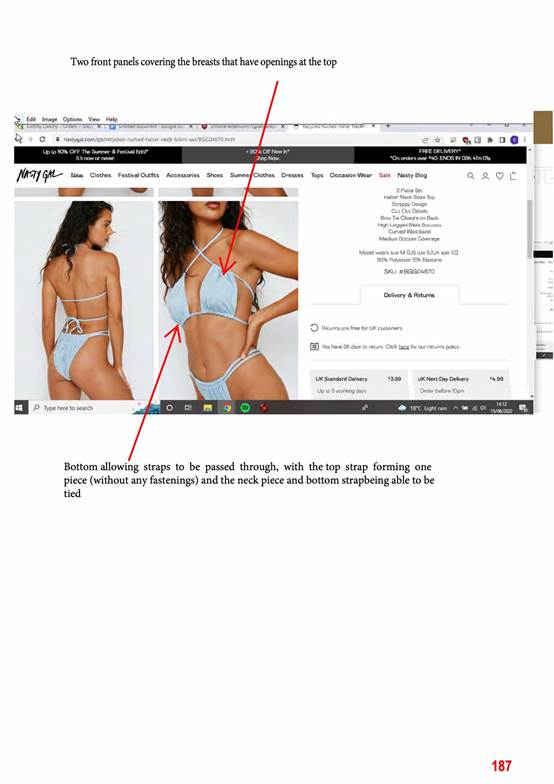

Design 1 - Bikini top

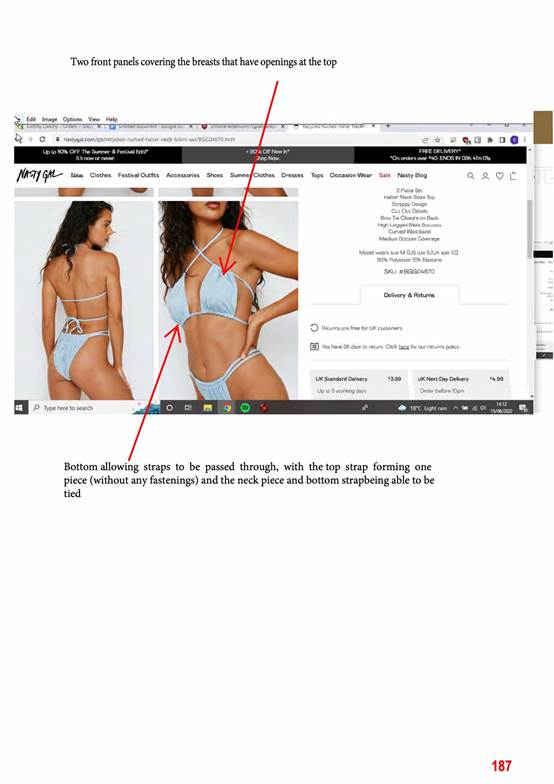

- The features relied on by the Claimant are:

i) the two front breast panels that have openings at the top and bottom allowing the straps to be passed through,

ii) with the top strap forming one piece (without fastenings), and,

iii) the neck piece and bottom strap being able to be tied.

- The issue and extent of subsistence of design right for Design 1 is tied up with the date at which it came into existence. This is because the bikini top designed by the Claimant is what is known as a "multiway" design. This means that the straps can be threaded in different ways through the panels to allow the garment to be worn in different ways. The interaction matters because the Claimant first designed the panels in 2011, to be worn with straps in a number of different configurations which she says are different to Design 1. Shown below is the 2011 version:

- Note that the Claimant herself sought to promote the versatility of the design - which is achieved by threading the straps differently. See for example the third design from the left in the 1st and 3rd rows above which both have the tie for the top strap positioned between the panels.

- The relevance of this is that if 2011 is the date at which an article was first made to the design, then design right would have expired before the first acts of alleged infringement by the Defendants.

- It was not until March 2016 that the Claimant first showed the straps threaded through the panels and configured round the body in the way shown in Design 1 on her cwtchycwtchy website. The following display could be found on her Instagram page in 2016 and illustrates Design 1 (see the second design on the third row) as compared to the other older "box" designs:

- The Claimant explained in her oral evidence that Design 1 utilised the same pieces of fabric over the breasts, but the straps were threaded in a different way to achieve the particular shape and configuration shown in Annex 1 to this judgment. In particular, the ends of the straps are such that they are tied at the neck and bottom strap (integer (iii) of the design).

- I heard evidence from the Claimant that this was an unusual way of arranging the straps and panels, not least because, as shown on the mannequin in Annex 1, the middle strap is continuous round the back and so the bikini top needs to be put on over the head of the wearer before the top and bottom straps can be tied. The Defendants did not challenge this description.

- The Defendants had two criticisms of the Claimant's definition of Design 1. First, they said that because the panels and straps were the same for the 2011 design as for Design 1, just arranged differently, then 2011 was the date on which the design first came into existence. This was in fact the date that the Claimant had originally relied on in her pleading. Alternatively, they submitted that the features identified by the Claimant did not describe a protectable shape and configuration. Instead, they were either concepts and methods of construction or abstract clusters of features which are not protectable according to the case law I have cited above.

- The Defendants pointed to the Claimant's features "openings at the...bottom allowing straps to be passed through", "forming one piece" and "being able to be tied". They submitted that these features remain constant, whatever the shape and size of the bikini, indicating that shape and configuration was not being claimed.

- Further, they submitted that the particular formulation of which strap is tied and which one is 'one-piece' depends on the choice of the wearer. They pointed out that the top strap is a long, single strap that can be wrapped around the neck or back, and/or twisted on the front, and can be tied behind the neck or tied behind the back. Which way the ends of the strap go is the wearer's choice and is not the shape or configuration of the design.

- In cross examination, Ms. Edwards accepted that integer (i) of the design was present in her 2011 bikini. What she asserted was different was the arrangement of the straps, with the tie at the neck and bottom strap (integer (iii)) and the top strap forming one piece (integer (ii)).

- I agree that the straps are shown differently in the 2016 version. Instead of threading the top strap starting from the outside of the breast panels (far left or far right), the strap is threaded from the centre, through one panel, and then round the back through the other panel so that the ends of the strap can be tied in the middle (around the neck). This is the same threading arrangement as I have identified in the two 2011 versions on rows 1 and 3 above; it is just that the length of strap with the tie has been extended between the panels and positioned around the neck and the loop that was around the neck is now around the back.

- Accordingly, the only difference between the 2011 design and the 2016 design is that, as worn, the top strap is threaded with the ends in the middle, between the panels, and tied around the neck. But this threading arrangement is already shown in the 2011 screenshot. The only difference is the way that the straps are positioned around the wearer's neck and body. Taken off the wearer, the shape and configuration of the bikini top is the same, save perhaps for adjusting the length of the straps between the panels - which would occur to some extent in any case depending on the precise body shape of the wearer.

- I do not consider that this merits a fresh design right accruing in 2016. There is insufficient originality in the decision to thread the straps and position them around the body as claimed. Alternatively, the threading features ((ii) and (iii)) are mere methods or principles of construction and are already part of the 2011 design in any event.

- In short, the only difference between the 2011 and 2016 versions of the bikini is the position of the top tie (around the back or at the neck). Otherwise, the shape and configuration of the bikini is the same. The precise position of the top strap/tie on the body is an insufficient change to amount to the fresh creation of a protectable design right.

- Indeed, I suspect the motivation of the Claimant's then advisors in repleading Design 1 to move it from 2011 to 2016 was primarily because otherwise the alleged infringement would have arisen too late. Where any changes are too minor or are insufficiently protectable to merit a fresh design right accruing, the court should be alive to the dangers of "evergreening".

- Even if I ignore the change in position, dealing with the design as currently pleaded, I reject the claim that design right subsists in Design 1 from the claimed date of March 2016.

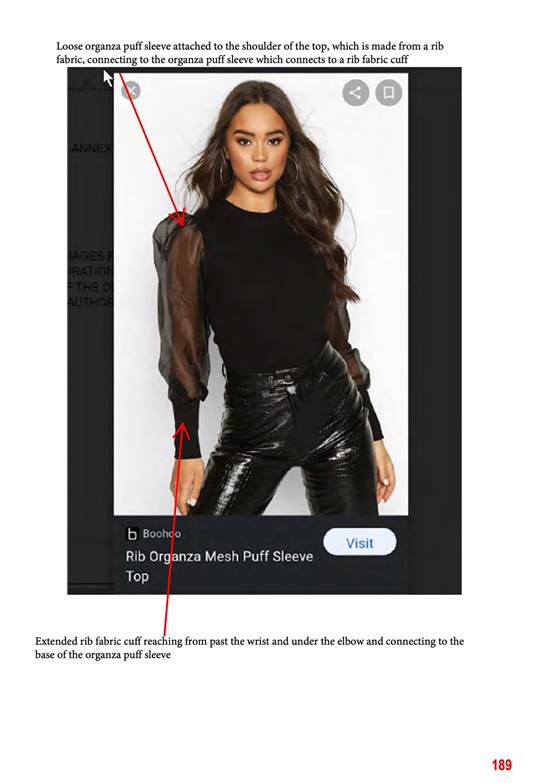

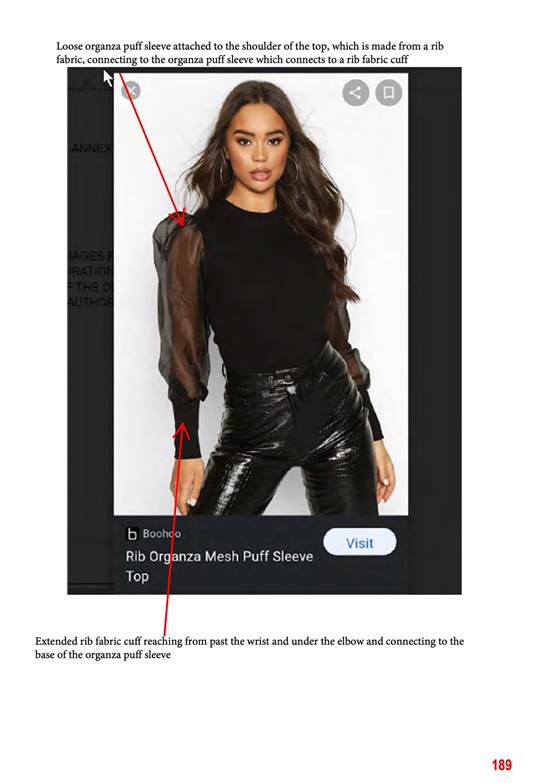

- In relation to Design 2 the Claimant relies on the following features of shape and configuration:

i) an organza puff sleeve made from rib fabric connecting to a rib fabric cuff and a rib fabric top;

ii) the extended rib fabric cuff reaching from past the wrist and under the elbow and connecting to the base of the organza puff sleeve.

- Note that these features relate only to part of the sleeve of the garment. The rest of the garment is not described and largely not shown. This is permitted by the reference in s.213 (2) CPDA 1988 to the shape or configuration "of the whole or part of an article".

- The evidence established that this design was first made available via the Claimant's Facebook page in December 2013. It was also shown on a model in 2014.

- The Defendants objected to the subsistence of the design as a matter of principle. They submitted that the looseness and puffiness of the sleeves depended on the wearer's choice i.e. the wearer could push the sleeve up the arm. There was no reliance on any particular size, shape or dimension.

- The Defendants also submitted that the claim to a cuff reaching from 'past the wrist' to 'under the elbow' was subjective and determined by the length of the wearer's forearm. It was vague and covered most cuffs of sleeves. It would be impossible to determine what constitutes an 'exact or substantial' part of being 'past the wrist' or 'under the elbow', yielding an impermissible degree of protection. The Defence showed earlier examples of sleeves which the Defendants contended would be caught by the definition, seeking to illustrate the vagueness of the plea and the lack of originality in describing it this way. However, in these designs the cuff was much shorter, and not extended as shown in the depiction of Design 2.

- I agree that the design cannot be defined by reference to the way it interacts with the wearer, as that will vary from person to person for the same design of fabric. I therefore reject the attempt to define the design by reference to the wrist and elbow of the wearer. I also agree with the Defendants that design right cannot include the nature of the material being used (i.e. organza or rib fabric), which would amount to a method or principle of construction.

- So in my judgment all that is left of the pleaded design is a "puff sleeve" connected to an "extended cuff". In the representation of the design which is pleaded, the cuff is approximately the same length as the puff sleeve.

- Does this retain sufficient originality to be deserving of the protection of design right?

- The decision is borderline. For the Defendants Mr Kershaw pointed out that organza products were sold as a throwback to the 1980s. He exhibited a number of examples which he said pre-dated Design 2. It is right that a number of these show sleeves similar to that in Design 2, but none have the longer cuff which is a claimed feature of the design.

- Accordingly, I am just persuaded that there is sufficient originality in what remains of Design 2 for design right to subsist. This supported by the absence of evidence of longer cuffed sleeves in the material relied on by the Defendants in their Defence, and the absence of any reliance on the design being commonplace.

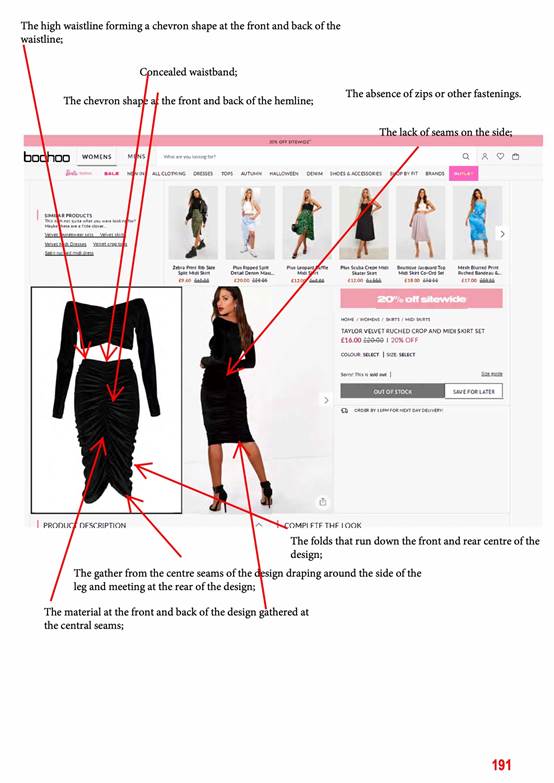

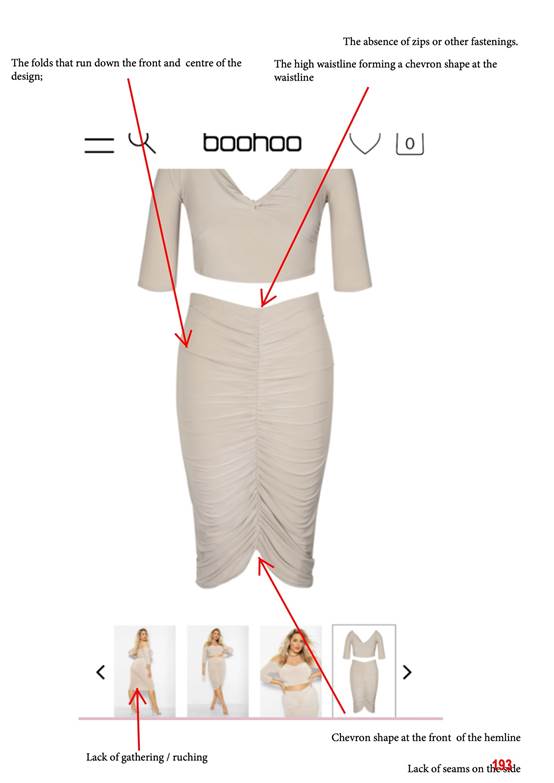

Designs 3 & 4 - Ruched Skirt

- I can take these together because the only difference between them is that the back of the skirt in Design 4 is flat and not ruched (thereby excluding "and back" in feature (v) below). I find that both these designs were first made available by the Claimant on social media in late 2013. I reject the suggestion that Design 3 first appeared in 2014 through a catwalk display - contrary to the evidence of the Claimant, the December 2013 social media posting is of a dress with the same waistline. Design 4 was put on social media by the Claimant in November 2013, as originally pleaded by her in these proceedings. They are of a style referred to in the industry as "Bodycon" (standing for body conscious). These are tight fitting garments exemplified by wearers such as Kim Kardashian, although the Claimant claims to have pre-dated her use.

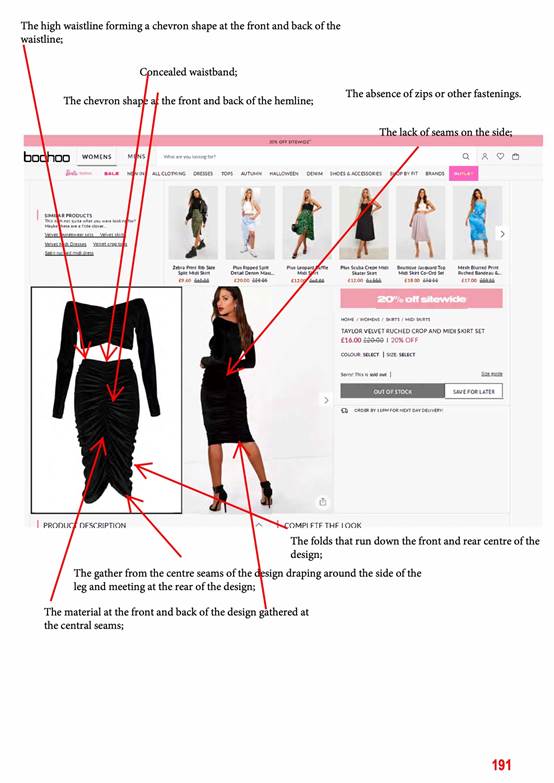

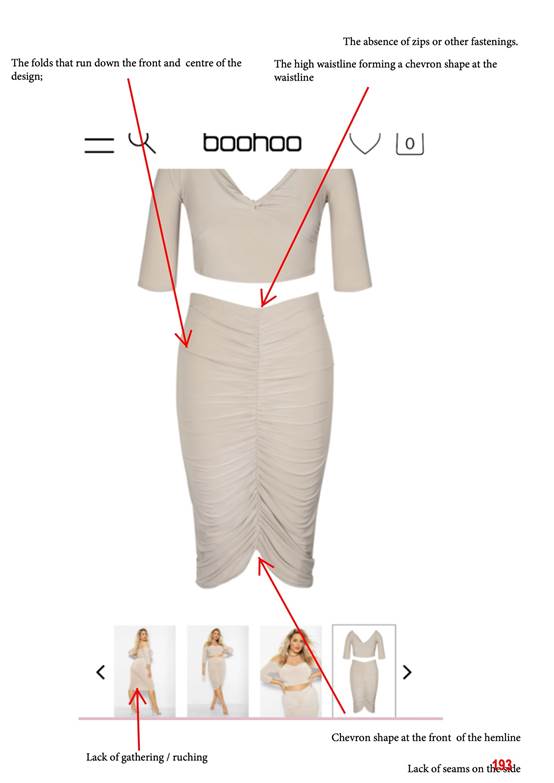

- The Claimant relied on a multiplicity of features for these designs, as follows:

i) The high waistline forming a slight chevron shape at the front and back of the waistline;

ii) The slight chevron shape at the front and back of the hemline;

iii) The concealed waistband;

iv) The lack of seams on the side;

v) The material at the front [and back] of the design gathered at the central seams;

vi) The overall shape and fit;

vii) The folds that run down the front and rear centre of the design;

viii) The gather from the centre seams of the design draping around the side of the leg and meeting at the rear of the design; and

ix) The absence of zips or other fastenings.

- The Defendants object to reliance being put on features that are not present, cannot be seen and/or form no part of the shape and configuration, such as the concealed waistband, the absence of seams, zips or fastenings.

- I agree - it is only those features which can be seen in an article which can be protected - see Rolawn and Albert Packaging. Features (iii), (iv) and (ix) should be excluded, along with (vi) which adds nothing. For the reasons given above any features which depend on the precise shape of the wearer should also be disregarded. This includes the "high" waistline. So what is left is the chevron shape at the back and front of the waist (i) and hem (ii), the ruching which is gathered in the centre on the front or back (Design 3) or at the front only (Design 4) (v) & (vii) and the draping at the leg which follows from the combination of (ii) and (viii).

- There was a debate in the evidence as to whether the dress could be worn to the side so that the features above are effectively rotated 90 degrees. It was accepted that it could but I do not consider that that changes the overall shape and configuration of the dress relied on which, after all, must ignore the position of the wearer.

- It was also said by the Defendants that the folds amounted to surface decoration. I disagree. The ruching is distinct and three dimensional and goes beyond mere surface decoration.

- Although there was some evidence as to the ubiquity of ruching, again, noting the absence of a properly formulated plea of commonplace, I am prepared to accept that there is sufficient originality in the Claimant's designs for design right to subsist in the features I have identified.

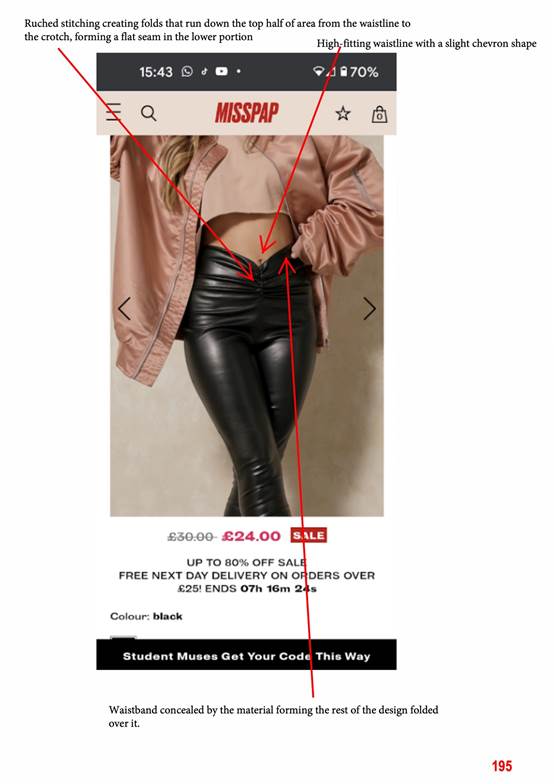

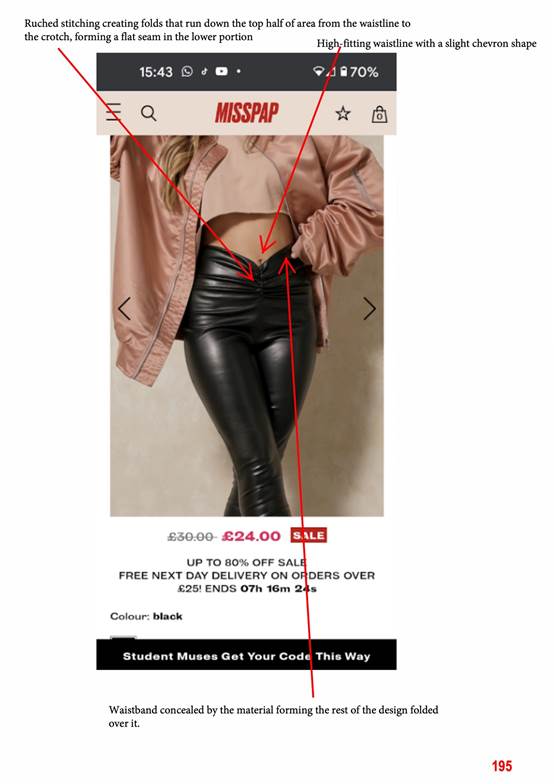

- The features relied on are as follows:

i) Ruched stitching creating folds that run down the top half of area from waistline to crotch, forming a flat seam in the lower portion;

ii) High fitting waistline with slight chevron shape;

iii) Waistband concealed by the material forming the rest of the design folded over it.

- For similar reasons to those expressed above, I do not consider that design right can subsist in what is said to be a high fitting waistline, or a concealed waistband. What is left is a pair of ruched leggings with a "small" chevron at the top, and with ruching only present in the top half of the area between the crotch and the waistline. The Claimant confirmed that it was only the front part of the leggings that were relied on.

- This is barely enough to comprise a subsisting design but I consider it just passes the necessary threshold. The relative simplicity of the design might suggest that it would be easy to prove that it was commonplace, but as noted above that was not a point advanced by the Defendants.

- The Claimant's pleaded case was that this design was first made available in 2016. However, in cross examination it was put to her that the same design was worn for her on the 2011 NEC Diet Coke catwalk:

- The Claimant disputed this on the basis that these leggings were "lowrise" and the top was a "V" and not a chevron. I have rejected the former feature as not being a relevant part of the design and I reject the latter suggestion as a matter of fact. Design 5 was first made available in 2011.

- This involves consideration of several disputed factors:

i) whether there has been copying of the Claimant's designs;

ii) whether the alleged infringements are made exactly or substantially to the Claimant's designs;

iii) for the purposes of primary infringement under s.226 CPDA 1988, whether the Defendants have made the articles or authorised their making; and,

iv) for the purposes of secondary infringement under s.227 CPDA 1988, whether the Defendants had the necessary reason to know or have reason to believe that the Articles were infringing articles.

Number of Alleged Infringing Articles

- The Claimant has sought to rely on multiple infringements for Designs 2 to 5. The Defendants say that this is contrary to the direction of the Court made in an order dated 20 March 2023 whereby HHJ Hacon ordered in §2:

The Claimant shall have permission to file and serve within 28 days of this Order Amended Particulars of Claim. The Amended Particulars of Claim, if filed and served, shall plead infringement of no more than five (5) designs in which unregistered design right subsists and no more than one (1) article alleged to infringe each design relied on. The Claimant shall plead no other intellectual property right.

- Those pleading the Claimant's case at the time have attempted to circumvent this by trying to group each of the alleged infringements with words such as "For the avoidance of doubt, the First, Sixth and Eighth Defendants have offered for sale the same design being the Leather Front Ruched Leggings [Design 5] save in different colours or materials". The alleged different materials include material which is not leather.

- The problem I face is that there were at least two further hearings about the state of the pleadings, resulting in orders dated 26 September 2023 and 17 May 2024. There was a dispute between the parties before me as to whether the issue of the additional alleged infringements had been raised by the Defendants and/or dealt with by HHJ Hacon at these hearings. I do not have transcripts of the hearings and I was not addressed in detail as to what was said at each of them; there simply was not time in the course of an already compressed trial to deal with this.

- In summary, the number of alleged infringements appears to be in excess of those permitted by §2 of the March 2023 Order. At the same time there does not appear to have been a successful attempt to strike out the pleading. It also appears to be disproportionate to attempt to carry out an archaeological exercise to try to work out who said what or who should have said what at one of the earlier hearings.

- I consider that the Claimant should be held to one example each of the alleged infringements. Indeed, this is how the Amended Particulars of Claim deals with them - at Annexes 17-21, which are reproduced as Annex 2 at the end of this judgment. I will therefore rely on those annotated alleged infringements. However, in case it matters I will also deal with the additional items and pick up any factual differences in the following sections on copying and similarity. Where there are multiple alleged infringing articles I refer to them as e.g. alleged infringing article 5(iv) to represent the fourth version of the alleged infringement of Design 5.

Copying

- In order to determine the issue of copying it is necessary to understand how the Defendants typically go about launching a new design of clothing. Whilst the precise breakdown may vary between the different defendant companies, the witnesses explained the general practice as follows.

- Mr Kershaw, boohoo's General Counsel, gave evidence of the scale of the Defendants' businesses. He explained that on average each of the defendant companies places hundreds of new garments for sale on its website each week, with the Sixth Defendant alone placing over 800 new products per week. This truly is "fast fashion". Further, the design teams within each defendant are relatively small (10-15 designers), meaning that each designer is churning out multiple garment designs per day. It is therefore not surprising that ideas are constantly re-used during the design process.

- Mr Blacklock, who is responsible for the buying, design, merchandising and Q&A teams at the First Defendant, explained that about 50% of the First Defendant's products are designed in-house. The remainder will be designed by third parties and offered to boohoo for sale. The in-house design process is influenced by what is going on in the fashion world and what celebrities are wearing. It also includes looking at social media. In some cases a trend board will be sent to the manufacturer; in other cases a specific design will be requested.

- Mr Binns, Chief Operating Officer of the Sixth Defendant, characterised the design process as occurring in one of four ways. Some garments - the higher price point items amounting to 10-15% of products - are "designer developed" by one of the 14 designers in the company. The majority of others - some 75% of the total - are "buyer developed" whereby the buyers will look at current trends and ask suppliers to prepare samples before production. In his oral evidence he explained that inspiration was taken from a range of different sources, including catwalks, designers and social media. In the case of catwalks, he added that this would be catwalks in the 12 to 18 months prior to the design process. The remaining products are designed by suppliers and offered to the Sixth Defendant with a minority of these coming "off the rack" from global wholesalers.

- Mr Kershaw expanded on this in his oral evidence. He accepted that on occasion the Defendants would send images from social media (e.g. Instagram) of clothing made by other brands to their manufacturers for supply to the Defendants. The design document (using the wording of the Seventh Defendant) would include the wording "Nasty Gal owns all intellectual property in these designs including but not limited to registered and unregistered designs, goodwill and copyright, and shall take legal action in line with the supplier Terms and Conditions should these rights be infringed" even though the original design might have been a photo of a garment made by another brand (one example in evidence was from the brand Lahana Swimwear). Mr Kershaw explained that this stock wording was designed to indicate to the manufacturer that it did not have any rights in the design of the goods it was making for the Defendants.

- Mr Kershaw referred on a number of occasions to the "sources of inspiration" used by the Defendants. As I put to counsel for the Defendants, it is clear that this phrase is on occasion a euphemism for a pattern of behaviour which involves the direct copying of garments found on social media, as occurred in relation to the bikini bottoms accompanying Design 1 and the leggings of Design 5 (see further below). As Mr Kershaw went on candidly to explain "typically, our buyers and designers will look at Instagram for sources of inspiration. They will look at high−end designer. They will follow the catwalk trends. They will share information from Pinterest and other sources." However, he maintained that he was not aware, and had found no evidence, that any of the Defendants' designers had at any time seen any of the Claimant's garments and used them as a source of inspiration. He pointed out that typically such designers would follow more higher-end accounts or accounts with greater numbers of followers than the Claimant.

- I asked Mr Kershaw about what steps the Defendants took to make sure that the rights of third parties were not infringed when using such "sources of inspiration". He explained that the design teams were given training in relation to design right and copyright law. The evidence is silent as to whether any due diligence was carried out in relation to the designs used for the alleged infringing items in the present case and Mr Kershaw was unable to give further details.

- As for documentary records, Mr Kershaw confirmed that the number of documents which had been turned up in disclosure was limited because many of the individuals who were involved with the design/purchase process of the garments in dispute were no longer employed by the Defendants and their inboxes were deleted in accordance with the Defendant companies' policies. It will be apparent from the enormous turnover of products that this means that large numbers of documents relating to the design of products will no longer exist.

- With that general background I turn now to the specific evidence in relation to the creation of the alleged infringing items.

Design 1

- I deal with this in case I am wrong about the absence of design right in the pleaded 2016 version.

- The alleged infringement of Design 1 was designed by Emily Hale in early December 2021. Ms. Hale was and remains an employee of the Seventh Defendant. She was not called to give evidence and instead Mr Kershaw spoke to her and reported what she told him as a matter of hearsay. The Defendants explained that this was in part because they were restricted to the number of witnesses they could bring to trial (three) and given the number of defendants and number of alleged infringements they chose to bring appropriate representative witnesses instead.

- I have some sympathy with the Defendants' position, and I found Mr Kershaw to be an honest witness genuinely trying to help the Court. However, it is regrettable that decisions were taken for (understandable) case management reasons which prevented the primary witnesses on copying from attending trial.

- It is also regrettable that although, again for understandable case management reasons, Practice Direction 57AC does not apply in the IPEC, nevertheless parties do not seek to adhere to it where they can.

- In other words, I would have been assisted in my determination of the issue of copying if Ms. Hale had provided a witness statement which followed the guidance in PD 57AC. As it is, I will have to do the best I can with the material before me, to which I now turn.

- The evidence from Mr Kershaw was as follows.

- The NastyGal bikini was designed in-house by Emily Hale who is described in her email footer as "Assistant Designer - Swimwear, Beachwear, Lingerie and Nightwear".

- On 1 & 2 December 2021 Ms. Hale shared her proposals for new ranges of swimwear known as 'urban' and 'editor' with a junior buyer, Georgia-May Bartosz. The 'editor' line-up was as follows:

- The second design from the left in the top row is the relevant one for present purposes.

- Following this exchange, on 3 December 2021 Ms. Hale sent an email to a manufacturer based in China for sample development enclosing the editor "Tech Pack". The Tech Pack contains CAD drawings which Ms Hale created with technical specifications for size, colours, and instructions for manufacture. According to Ms. Hale, the CAD for the NastyGal bikini in dispute is the image which is labelled with the style code MAYEDITOR002EH in the Tech Pack. It is shown first with a palm-tree print and then in a block colour described as Pantone shade 'subdued blue 14-4209'.

- The CAD in the Tech Pack includes instructions that the NastyGal bikini top should be a "RUCHED BIKINI TOP SHAPE TO BE AS GARMENT IMAGE 1" with the bottoms as GARMENT IMAGE 2. Garment Image 2 was an image taken from Pinterest - but for the purposes of this dispute only Garment Image 1 matters. Both are shown below:

- Pausing there, note that the instructions sent to the manufacturer were apparently not to create a bikini top resembling the Claimant's Design 1 with the top tie between the panels. Instead, a more conventional bikini top was sought, both in the general CAD drawing and the specific ones.

- Further, Mr Kershaw recorded that Ms. Hale had confirmed that she has never previously heard of Ms. Edwards, Cwtchy Cwtchy or seen any of the Claimant's designs, including the First Design.

- I also note in passing that the design drawn by Ms. Hale resembles more closely the Claimant's 2011 bikini top designs prior to her arriving at the alternative Design 1 in 2016. Further, in 2016 the Claimant sought to rely on these earlier 2011 designs in a complaint against the Defendant's sales of bikinis similar to the design which Ms. Hale had sought from the Chinese manufacturer. This complaint is no longer pursued.

- All of this serves to emphasise the interchangeability between the various designs, which are all variations created using the same basic fabric panels and ties.

- Consistent with Ms. Hale's account given through Mr Kershaw, the tiger print bikini first went live on NastyGal's website (apparently on 27 July 2022) in the following form i.e. as instructed by Ms. Hale:

- However, the solid blue version appeared earlier and in a different form, which is the basis for the Claimant's complaint. Instead of appearing in the same design as the tiger print, it appeared from at least 15 June 2022 (as captured by the Claimant) in the three tie design resembling Design 1 (requiring it to be put on over the head of the model, as noted above):

- The Defendants' evidence is that this was a mistake which occurred during the photo shoot. Mr Kershaw was unable to tell me how the garment would have been delivered by the manufacturer (i.e. with ties already installed, or with ties separate from the breast fabric which then needed to be threaded by the user).

- It is said that when Ms. Hale noticed this she asked for the garment to be sent back to the photographic studio and alternative photos to be taken. Internal documents were disclosed recording a request for photos for a garment with the same item number and description on 23 June 2022 (i.e after the alleged infringing design went live). Mr Kershaw's evidence was that the bikini was rephotographed and checked out on 30 June 2022. He explained "I understand from Ms Hale that styling errors do occasionally happen when there are multiple ties to a product or different ways of wearing a product."

- The resulting image (which is not alleged to infringe Design 1) was then added to the Seventh Defendant's website:

- It is not clear whether at the same time as the above image was added to the website, the original image was removed or left up.

Assessment

- This is the most difficult factual dispute to resolve in the trial. That is why the Court would have benefitted from direct evidence from Ms. Hale. Was the creation of the alleged infringing design mere coincidence, or has there been a cover-up by the Defendants (no pun intended)?

- In spite of the incomplete nature of the evidence, I am satisfied that, even if valid, there was no copying of the Claimant's design in the creation of the Nastygal bikini. This is for multiple reasons, many of which apply equally to the other alleged infringing items in the case.

- Firstly, the opportunity for copying was extremely limited. I accept the evidence that the design of the bikini did not specify the straps as shown in Design 1. So it seems that the alleged infringing design was only created for the first time in the photo studio. I find it extremely improbable that the persons responsible for the photo shoot would have searched online for hints as to how to wear the bikini and found the Claimant's designs. Instead, it is much more likely that they assembled the cloth and straps themselves in the way that it can be seen being worn by the model. Alternatively, any of them might have had experience of "multiway" bikinis and suggested it be worn accordingly.

- Secondly, the time elapsed between the Claimant's publication of Design 1 (assuming a 2016 creation) and the design of the alleged/infringing bikini and/or the photo shoot. It is inherently improbable that even if someone involved had searched online for bikini designs, a design made some 5 years earlier would have appeared. This is particularly given the case that the Defendants' influences seem to be social media feeds rather than Google searches, which are normally organised by date, and the aim would be to reflect current fashion trends.

- I note that the Claimant has not put forward any evidence that her designs had become "stock" photos on social media sites such as Pinterest, which might have compensated for the passage of time between publication on her own social media feed and alleged copying.

- Thirdly, and combined with the previous point, is the relatively low profile of the Claimant's own social media channels. The contemporaneous material shows that the Claimant had only a handful of likes and comments on the Facebook pages showing her designs over the relevant period. Her Instagram account Scrunchbooty had just 268 followers in 2020.

- I accept the Claimant's submission that the numbers of people on social media were much smaller in 2012. The Claimant also pointed out that she had been found by Vogue despite her small social media following - so she had sufficient visibility to be noticed. Again, I accept that. But that does not do enough to establish that at the time any of the alleged infringing designs were made the Claimant's profile was big enough to make it likely that her postings would have been one of the sources of inspiration for the Defendants' articles. The numbers of followers and likes for her publication of Design 1 are just too small to make it likely that the Defendants would have come across it many years later.

- Fourthly, I flatly reject the suggestion by the Claimant that the Defendants would have used any depictions of the Claimant's designs which had been sent to Mr Kershaw or other members of the legal department by way of complaint. Although the Defendants were technically in possession of a large number of the Claimant's designs as a result of her voluminous correspondence with them, I reject any suggestion that these designs would have been passed on to the design team. That is inherently improbable in a situation where the Defendants were expending time and money in trying to persuade the Claimant that there were no infringements of her rights.

- Fifthly, the improbability of the above needs to be compared with the much higher probability that, given that the cloth and ties are identical as between Design 1 and Ms. Hale's non-infringing sketches, someone might have put them together in the same way as depicted in Design 1 without copying. That is a function of the low originality of the Claimant's design (assuming validity), which is generic enough that other people in the industry are quite capable of coming up with the same design independently. There are only so many ways to wear a multiway bikini such as the Claimant's, and given the very high volume of products, including bikinis, being made by the Defendants each week, it is not surprising that a case has arisen whereby one has been worn in the same way. The high level description of the design also makes it impossible to find any telltale indications of copying.

- Finally, I note that there is no suggestion in the Defendants' publicity that the alleged infringing design is or can be used "multiway". Had there been copying of the Claimant's material it might have been expected that the Defendants would wish to advertise this fact.

- For all these reasons and in spite of the evidence from Mr Kershaw indicating that designs are copied from social media on occasion by the Defendants, I reject the suggestion that the Claimant's Design 1 has been copied in the present case.

Design 2

- The alleged infringements of Design 2 (and alleged infringing articles 3(i), 4(i) and 5(iv)) are different to the others sold by the Defendants in that none of them originated in-house. All were instead designed and supplied by third-party wholesale suppliers, as evidenced by purchase orders. If they were copied from Ms. Edwards, any copying would have been carried out by the third parties.

- I have no way of telling how the third-party wholesale suppliers came up with these designs. However, the second to fifth points which I have made above in relation to Design 1 all apply equally here. In particular, the age of the Claimant's design, the low likelihood of an old social media feed with limited followers being copied and, given the very low originality in the design, the coincidental chance of someone coming up with a similar design all apply. On the balance of probabilities I find that copying has not taken place.

Designs 3-5

- At least one of the alleged infringing versions of each of these designs was created within the Defendants (as opposed to by a third party). In each case there is no documentary evidence one way or the other in relation to the derivation of the alleged infringements (apart from in two respects in relation to the alleged infringements of Design 5).

- I accept Mr Kershaw's evidence about the routine deletion of records and emails in the Defendant companies, and I also note the very large number of documents which must be generated to support the enormous turnover in designs offered by the Defendants. So I am not willing to make adverse findings about copying by the Defendants just because the records have not been disclosed. Further, I note that adverse documents were turned up as a result of the disclosure exercise, so I reject any suggestion that material has been deliberately destroyed or withheld.

- Further, as noted, my second to fifth reasons given above in relation to Design 1 apply equally to the other designs. The probability of the Claimant's designs being used as inspiration by the Defendants is very low given the passage of time and the reach of the Claimant's feeds. Moreover, the low originality of the designs means that it is much more likely that any similarities arose as a matter of happenstance given the very high volume of goods and limited design space inherent in producing garments to fit the human body. So once again on the balance of probabilities I find that copying did not take place.

Bohorose

- There are two additional points arising in relation to alleged infringements of Design 5. In relation to 5(i), Mr Kershaw explained that Katie Green was a buyer employed by boohoo who was involved in this design. According to her, the inspiration for the boohoo legging was found on Pinterest and sent to the supplier with the following notes:

- Mr Kershaw also explained that the Defendants had sought to perform a reverse-image search of Pinterest during the preparation of this case in order to try to find the image used, but had not succeeded. However, it had been possible to find the same item still being sold on Etsy, as follows:

- In other words, what seems to have happened is that the First Defendant asked its supplier to copy a design found on Pinterest that can also be connected to an Etsy account in the name of Bohorose. This is consistent with the evidence from Mr Kershaw that on occasion the Defendants ask for items to be copied.

- The Claimant had previously complained in 2020 about a design sold on Etsy and Depop by Bohorose. It was taken down by Etsy but then reinstated. The Claimant asserted that this was "without providing any prior art" and that Bohorose had also been selling Chanel jewellery on her Depop page for £12.00 (thereby seeking to insinuate that Bohorose was herself a copyist, and that the Bohorose leggings might have been copied from the Claimant).

- None of this is relevant to the issues I have to decide. Nor was it properly the basis of pleadings or evidence. I am therefore not in a position to assess whether the design complained about by the Claimant in 2020 was the same as the design utilised by the First Defendant, nor whether it was a copy of a design of the Claimant. For all I know, and consistent with my other findings above, Bohorose may have arrived at a similar design to that of the Claimant completely by chance.

- Further, the Claimant's reference to the provision of "prior art" (which was repeated on a number of occasions during the trial) is a reference to the law relating to registered designs (which the Claimant is the proprietor of for clothing unrelated to the present case). Indeed, from what I understand, the complaint to Etsy by the Claimant was on the basis of a registered design and not Design 5 relied on the present case. Registered design cases often turn on the question of validity and the provision of a single piece of relevant prior art may be sufficient to invalidate a registered design. But there is no requirement to demonstrate copying in such cases - a registered design may be infringed by someone who is completely unaware of the registered right. In contrast, to demonstrate the invalidity of an unregistered design right requires, amongst other things, the provision of multiple examples of prior art to demonstrate that the design is "commonplace". For infringement of unregistered design right it is necessary to show that the design has actually been copied and has been used as the basis for the infringement.

- Accordingly, even if I had material available to me with which to assess the Bohorose allegation, the action by Etsy to remove it in response to a registered design complaint can have no bearing on the question of copying in the present case. Moreover, the fact that the Claimant was previously relying on a different right not pursued in this case casts even further doubt on its relevance.

Winnie Harlow

- There was also a multicoloured version of the leggings alleged to infringe - 5(v). Mr Binns explained in his evidence that this was part of a collection which was created with the supermodel, Winnie Harlow. The trend board which inspired the collection was created in-house by Christopher Parnell who is employed as Head of Design by the Sixth Defendant, PLT. The images on the trend board include inspiration from the catwalk and garments previously worn by Ms Harlow:

- The trend board inspired the CAD which was also created by Mr Parnell:

- These garments were then ordered to be produced by a supplier for the Sixth Defendant.

- There is no basis to suggest that the Claimant's Design 5 provided any inspiration to Mr Parnell. The trend board made no reference to the Claimant's work and I reject any claim that there has been copying in this instance.

- Moreover, the documentation provided for this exercise illustrates the other major problem with the Claimant's case, namely the fact that in this field it is perfectly possible to come up with similar designs without there having been any copying.

Made exactly or substantially to the Claimant's designs

- If I am wrong about the existence of copying, I need to assess whether the alleged infringements are made exactly or substantially to the Claimant's designs. As noted above, the high level at which the designs are described makes it easier for the Claimant to succeed on this part of her case. In the circumstances I will therefore deal with the allegations briefly.

- In relation to Design 1, there was no real attempt by the Defendants to suggest that, if valid, their bikini was not made exactly or substantially to the Claimant's design. I agree. The bikini tops are extremely similar.

- For Design 2, the only features which I have found can sustain the right are the "puff sleeve" connected to an "extended cuff" and where the cuff is approximately the same length as the puff sleeve. In the alleged infringement shown in Annex 3, the cuff is much shorter. For this reason I find that that product was not made exactly or substantially to the Claimant's design.

- However, Article 2(ii), the Pretty Little Thing version shown in one of the photos in Annex 9 to the Amended Particulars of Claim, does have a cuff which appears to be the same length as the sleeve. Had the Claimant been permitted to rely on this garment as a matter of pleading, I would have found that it was made exactly or substantially to the Claimant's design:

- The features which I have held to be relevant to Designs 3 and 4 are:

i) The waistline forming a slight chevron shape at the front and back of the waistline;

ii) The slight chevron shape at the front and back of the hemline;

v) The material at the front [and back] of the design gathered at the central seams;

vii) The folds that run down the front and rear centre of the design;

viii) The gather from the centre seams of the design draping around the side of the leg and meeting at the rear of the design.

- Although it is difficult to make out some of the details of the alleged infringements from the figures relied on by the Claimant, these details are minor. Further, the chevron is less pronounced in the alleged infringements. I am prepared to hold that overall the Defendants' articles are made exactly or substantially to the Claimant's design.

- Finally, in relation to Design 5, I must consider the following features: a pair of ruched leggings with a "small" chevron at the top, and with ruching only present in the top half of the area between the crotch and the waistline.

- In the annotated alleged infringement in Annex 2 the ruching appears to run all the way down to the crotch of the leggings. On this basis I had considered that there was a sufficient difference such that the article was not made exactly or substantially to the Claimant's design. However, after circulation of my draft judgment, a better reproduction of the picture in Annex 2 was provided by the Claimant which shows that that ruching is only built in to the top half of the area between the crotch and the waistline. I find that all the alleged infringements of Design 5 (if the Claimant had been permitted to rely on the other alleged infringements) were made exactly or substantially to the design.

Infringing Acts

- Finally, I turn to the questions of primary and secondary infringement, assuming the designs are valid, have been copied and are sufficiently similar. For primary infringement, s.226 of the CPDA provides that:

"(1) The owner of design right in a design has the exclusive right to reproduce the design for commercial purposes—

(a) by making articles to that design, or

(b) by making a design document recording the design for the purpose of enabling such articles to be made.

(2) Reproduction of a design by making articles to the design means copying the design so as to produce articles exactly or substantially to that design, and references in this Part to making articles to a design shall be construed accordingly.

(3) Design right is infringed by a person who without the licence of the design right owner does, or authorises another to do, anything which by virtue of this section is the exclusive right of the design right owner."

- In relation to secondary infringement, s.227 of the CPDA provides that:

"(1) Design right is infringed by a person who, without the licence of the design right owner—

(a) imports into the United Kingdom for commercial purposes, or

(b) has in his possession for commercial purposes, or

(c) sells, lets for hire, or offers or exposes for sale or hire, in the course of a business,

an article which is, and which he knows or has reason to believe is, an infringing article. ..."

- In order to establish secondary infringement, the Claimant must show that the Defendants have 'dealt' in Articles (i.e. that they have carried out one or more of the acts listed in s.227(1) of the CPDA), that the Articles are articles produced exactly or substantially to the Designs; and that the Defendants knew or had reason to believe that the Articles were infringing articles.

- An "infringing article" is defined in s.228 of the CPDA as infringing "if its making to that design was an infringement of design right in the design."

- Guidance can be found as to the meaning of "knew or had reason to believe" from equivalent authorities on secondary infringement of copyright (see Whitby Specialist Vehicles v Yorkshire Specialist Vehicles [2016] FSR 5 at §48, per Arnold J). Of these, LA Gear Inc v Hi-Tec Sports Plc [1992] F.S.R. 121, makes clear at 129, per Morritt J., approved on appeal, that there is a requirement of 'reasonableness' which forms the backbone of the test for constructive knowledge:

"Nevertheless, it seems to me that "reason to believe" must involve the concept of knowledge of facts from which a reasonable man would arrive at the relevant belief. Facts from which a reasonable man might suspect the relevant conclusion cannot be enough. Moreover, as it seems to me, the phrase does connote the allowance of a period of time to enable the reasonable man to evaluate those facts so as to convert the facts into a reasonable belief."

- The Defendants' position on primary infringement is that none of the alleged infringements were made in the UK, as s.226(1)(a) requires. See Recorder Douglas Campbell KC in KF Global Brands v Lead Wear [2023] EWHC 1303 (IPEC) at §34. Further, the Defendants cannot be liable for authorisation of manufacture where the manufacture does not take place in the UK.

- However, there is an absence of evidence about the geographical site of manufacture of articles alleged to infringe Designs 2-5. All that could be said was that on average 50% of the Defendant's products come from overseas.

- Further, s.226(1)(b) prohibits the making of a design document recording the design for the purpose of enabling such articles to be made. I have referred to the evidence that the Defendants were involved in the making of design documents in the UK for the articles alleged to infringe Design 1 and Designs 5(i) and (v). There is a complete absence of documentary evidence in relation to the alleged infringements of Designs 3 and 4 - it is only in relation to Design 2 that there is a positive averment that the alleged infringement was made by a third party.

- In the circumstances I am therefore prepared to find that on the balance of probabilities the Defendants would have made design documents for all of the alleged infringements of Designs 1, 3, 4 and 5. There would have been primary infringement of these Designs had the other elements of the tort been made out.

- In relation to secondary infringement, the Defendants argue that there was no reasonable basis to understand that the articles might be infringing until the Claimants Amended Particulars of Claim were perfected. Prior to that there was instead a mass of ill-defined allegations made in the numerous emails sent by the Claimant to the Defendants and/or in the original pleadings in this action.

- I agree. I consider the relevant knowledge and belief only arose in the present case 14 days after service of the Amended Particulars of Claim, namely on 4th May 2023.

- Had I found there to be any copying of any valid design rights resulting in articles made exactly or substantially to the Claimant's designs, it would have been necessary to have analysed the dates when the design rights came into existence and the dates of the alleged acts to work out whether there was actually any infringement taking place within the relevant lifetime of the design rights. I have set out above my findings as to the dates that any design rights in the Claimants Designs first came into subsistence. I record here the dates of the first alleged infringing activities of each of the Defendants as pleaded in the Defence:

i) Article 1 was first offered for sale by D7 around April 2022;

ii) Article 2(i) was first offered for sale by D1 and D10 around May 2021. Articles 2(i) and 2(ii) were first offered for sale by D6 around November 2019.

iii) Article 3(i) was first offered for sale by D1 around September 2017. The date that Article 3(ii) was first offered for sale by D6 is unknown.

iv) Article 4(i) was first offered for sale by D1 around September 2020. Article 4(ii) was first offered for sale by D6 around March 2022.

v) Article 5(vi) was first offered for sale by D8 around November 2020. Article 5(i) was first offered for sale by D1 around March 2021. The dates when Articles 5(ii)-5(v) were first offered for sale by D6 is unknown. However, there is an order confirmation for Article 5(v) from 21 May 2021 and a Daily Mail article dated 15 July 2021 covering the launch of the Winnie Harlow collaboration of which Article 5(v) formed a part. In addition, there is a purchase order for Article 5(ii) dated 20 October 2021.

- Annex 3 contains a record of when the alleged acts ceased. I will not weary the reader further than necessary at this stage by setting out the relevant calculations based on the assumption that I am wrong about the primary findings I have made. If necessary the calculations can be made based on these dates.

Conclusion

- In summary, I dismiss the Claimant's claim in its entirety. The primary reasons are as follows:

i) Design right does not subsist in Design 1;

ii) In relation to the alleged infringement of Design 2 on which the Claimant is permitted to rely, the articles are not made exactly or substantially to the designs;

iii) In relation to all of Designs 1 to 5, I find that the Defendants did not copy the Claimant's designs.

- I recognise that Ms. Edwards will be disappointed in this outcome. She has campaigned for some time to shine a light on what she sees as injustice against the small designer in the fashion industry. I have no doubt that her grievances are sincerely held, but she has subjected the Defendants and others to a torrent of complaints over a period of many years. Regrettably, the complaints that I have had to adjudicate are misdirected, either as a matter of fact or law, or both. The Claimant's submission that the Defendants copied the designs that their legal department possessed as a result of earlier complaints made by her illustrates how extreme her position has become.

- I acknowledge that copying undoubtedly takes place within the fashion industry, particularly in fast fashion. Every time the Defendants ask manufacturers to reproduce images found on social media there is a risk of someone's design right being infringed.

- But the stark truth is that there are also only so many ways to design clothing to fit the human body. Given the enormous numbers of articles being churned out by the likes of the Defendants each week, it is completely unsurprising that as a matter of chance, some of these resemble articles designed previously by others, including the Claimant. Further, the abstract way in which the Claimant has described her designs (so that they are barely original) simply increases the chance that they might resemble other garments designed independently. And whilst the probability of chance reproduction in such circumstances is high, the likelihood of a fast fashion company using a social media feed with few followers published many years ago is low. It is for these reasons that I have dismissed the Claimant's suspicions about alleged copying by the Defendants.

- As previously directed, I will hear the parties in relation to any consequential relief on 3rd April 2025.

Annex 1 - Designs Relied Upon

Annex 2 - Alleged Infringing Items with Claimant's Commentary