This judgment was handed down remotely at 10.30am on 12 March 2025 by circulation to the parties or their representatives by e-mail and by release to the National Archives.

.............................

HIS HONOUR JUDGE HACON

Judge Hacon:

Introduction

- The Appellant, Mr Klemz, is the owner of UK Patent Application No. GB 2588415A ('the Application') and the inventor of the invention claimed. It has the title 'An apparatus for generating a force'.

- The Application was published on 28 April 2021. On 31 August 2023 an examination report raised objections, stating that it did not satisfy requirements under the Patents Act 1977 ('the Act'). Mr Klemz sought a hearing. He was provided with a pre-hearing report written by the Examiner dated 30 April 2024, followed by a hearing on 12 June 2024 attended by Mr Klemz in a video conference. At the hearing Mr Klemz was invited to comment on the objections raised. The Hearing Officer was Dr Laura Starrs.

- On 3 September 2024 Dr Starrs delivered her written decision, BL O/0849/24 ('the Decision'). She refused the Application under s.18(3) of the Act on three grounds: (i) the invention is not capable of industrial application contrary to s.1(1)(c) of the Act, (ii) the invention is not sufficiently enabled contrary to s.14(3) and (iii) the claims are not clear contrary to s.14(5)(b).

- Although the Hearing Officer apparently reached a conclusion about clarity, there was no express finding that the claims lack clarity in the body of the Decision. There were no submissions about it before me so I will assume that it is not pursued.

- This is Mr Klemz's appeal from the Decision. There is a respondent's notice filed by the Comptroller raising a further and alternative ground for refusing the Application, namely that the invention is not sufficiently disclosed in the Application to make it plausible that the invention will work.

- Mr Klemz represented himself at the hearing of the appeal, making his submissions in an admirably clear and well-presented manner. He had earlier filed Grounds of Appeal and a skeleton argument along with supporting documents. Anna Edwards-Stuart KC appeared for the Comptroller.

The nature of the appeal

- Pursuant to CPR 63.16(1), the general appeals provisions in CPR 52 apply to this appeal. CPR 52.21(1) provides that the appeal is limited to a review of the decision below unless the court considers in an individual case that it would be in the interests of justice to hold a rehearing. Where there is to be no rehearing, the appeal will be allowed only where the decision below was either wrong or unjust because of a serious procedural or other irregularity in the proceedings (CPR 52.21(3)).

The invention

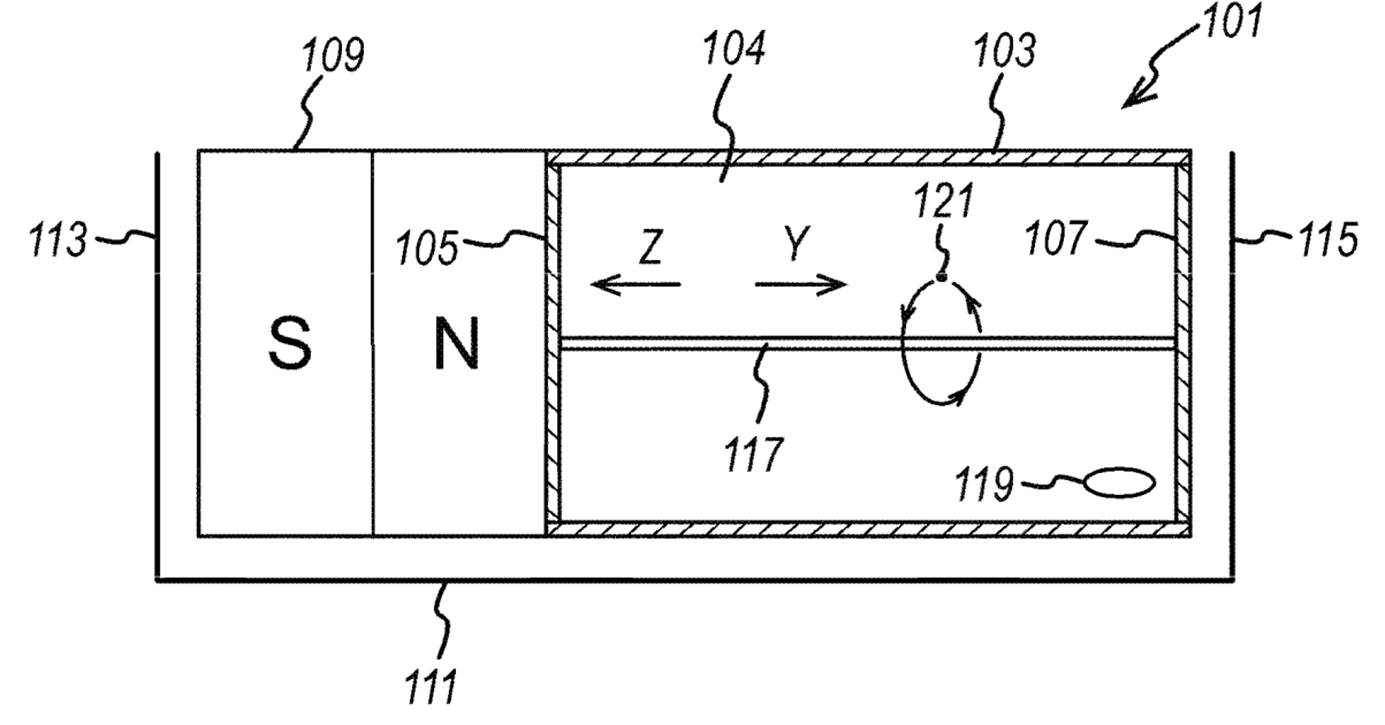

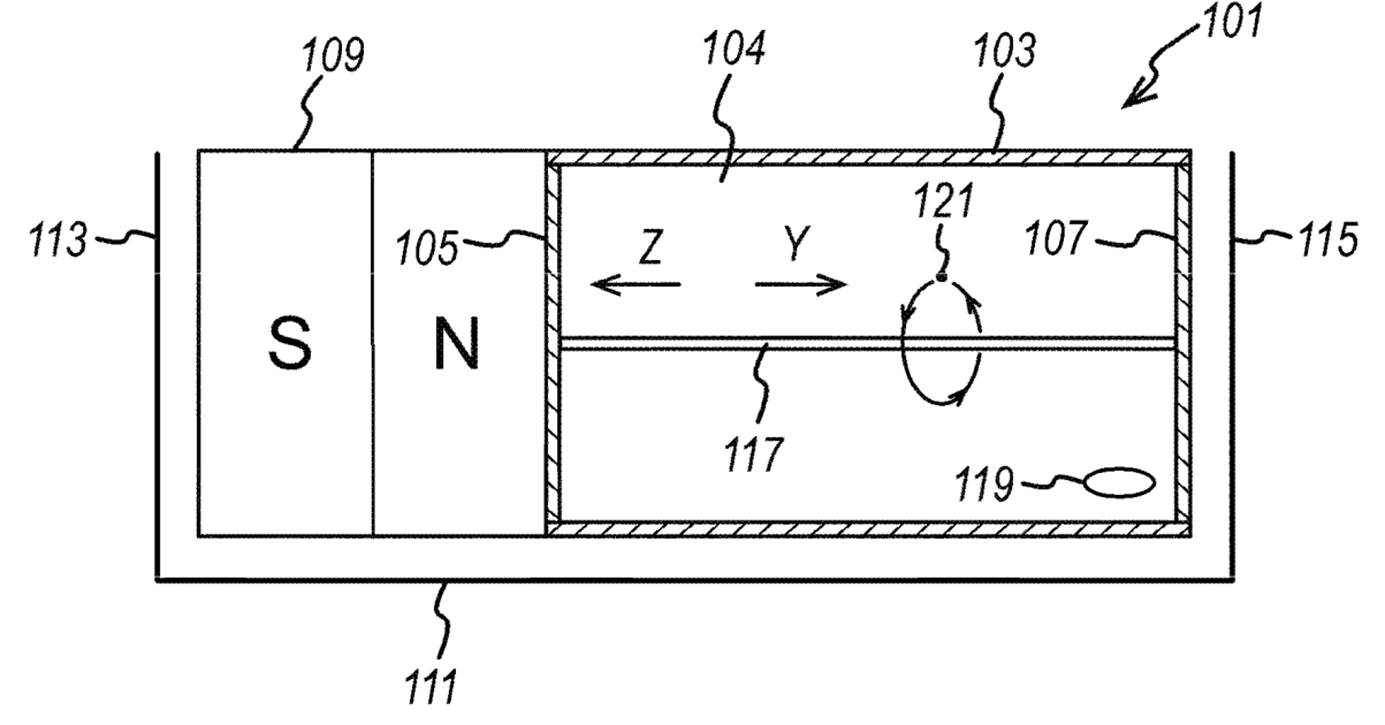

- This is Figure 4 of the Application:

- The apparatus 101 has a housing 103, 105, 107 with a cavity 104. Adjacent the housing is magnet 109 which creates a magnetic field in the cavity with non-parallel magnetic lines. The housing is shown contained within a magnetically permeable plate 111, 113, 115. An external power source is connected to an anode and to a cathode 117 located in the centre of the cavity. The housing acts as the anode. The potential difference between the anode and cathode creates an electric field between them. The cathode emits electrons which move radially away from the cathode towards the anode. One such electron is shown as 121. The magnetic field acts on the moving electron to create a Lorentz force on the electron which changes direction as the electron moves radially. Collectively the electrons make up a vortex. The vortex flow of electrons creates a second magnetic field which in turn creates a repulsive magnetic force pushing the magnet and the vortex of electrons apart. These repulsive forces are shown as Y and Z in Figure 4.

- The specification states that at any point in time the vortex of electrons is stationary in space pushing the bar magnet away from the vortex. The housing is connected to the magnet, so the whole apparatus is moved through space.

- As the magnet moves away from the vortex, the vortex experiences a reduction in magnetic flux. This induces an emf in the vortex which slows down the electrons, causing them to spiral outwards and fall into the anode. In effect, in this thrust mode, the deceleration of the electrons creates the thrust force on the housing. Momentum and kinetic energy are transferred from the electrons to the housing.

- In damper mode, the apparatus is in motion such that the magnet is moving towards the vortex of electrons. The vortex experiences an increase in magnetic flux and an emf is induced in the vortex which causes an increase in electron speed and current flow in the vortex. The effect is that the momentum and kinetic energy of the apparatus is transferred to the electrons, causing the apparatus to decelerate.

- The Hearing Office summarised the invention in her Decision:

'4. The application relates to the field of vehicle propulsion. Primarily, the invention is described in the context of propelling a spacecraft in space, as noted on page 25, lines 13-19 of the description as filed. Specifically, the present invention proposes an apparatus that does not require an exhaust for expulsion of reaction mass. It appears to require a magnet adjacent to a cavity which emanates a magnetic field into the cavity, wherein the cavity further contains a cathode and an anode, such that electrons are emitted from the cathode and travel through the magnetic field and to the anode. This arrangement is alleged to result in momentum and kinetic energy from the electrons being transferred to the magnet, and hence the apparatus housing (when the device is accelerating). In summary, acceleration of the device is alleged to be achieved from deceleration of the electrons by the magnetic field. The reverse applies when the device is decelerating (transfer of kinetic energy from the apparatus to the electrons is alleged to decelerate the apparatus).'

- Mr Klemz confirmed to me that this was an accurate summary of the invention.

- This is claim 1:

'1. An apparatus for generating a force, the apparatus comprising:

a housing having a cavity therein;

a magnet adjacent the housing, the magnet and housing arranged so that, in use, the cavity contains a magnetic field from the magnet, magnetic field lines within the cavity comprising non-parallel magnetic field lines;

a cathode capable of emitting electrons into the cavity; and

an anode,

the arrangement being such that, in use, the cathode emits electrons into the cavity and the electrons are deflected by the magnetic field from the magnet, such that a force acts between the magnetic field from the magnet and a magnetic field from the electrons and kinetic energy is transferred between the apparatus and the electrons.'

- The Hearing Officer discussed claim construction. I will quote this passage of her Decision in full because I asked Mr Klemz whether any part of it was inaccurate:

'15 Claim 1 requires 'an apparatus for generating a force'. When construed in view of accompanying description and drawings, claim 1 is considered to require an apparatus suitable for generating a force where the generated force acts on the apparatus itself and can be used to accelerate or decelerate the apparatus and any object to which the apparatus is attached. The description provides example uses of the apparatus including the propulsion of a vehicle, such as a spacecraft in deep space, an aircraft in the atmosphere, a road vehicle, a submarine, or moving a load on a crane. While claim 1 does not explicitly require the generated force to act upon the apparatus, I am of the view that this is implicit in view of accompanying description and drawings. This interpretation of claim 1 is also consistent with the skeleton arguments and the description given by Mr Kelmz [sic] at the hearing.

16 The description states that the apparatus can act both as a thruster and a damper, and in each case it is alleged to result in a force that either causes the apparatus to accelerate (when used as a thruster) or decelerate (when used as a damper). Claim 1 further requires the apparatus to have a housing comprising a cavity. A cathode emits electrons into the cavity in direction of an anode. In some embodiments a cathode is circumferentially surrounded by an annular anode. In other embodiments – the opposite arrangement is envisaged – a central anode is circumferentially surrounded by an annular cathode, see e.g. page 18 lines 11-15 of the description as filed.

17 A magnet is provided adjacent the housing such that non-parallel magnetic field lines are within the cavity in use. The claim does not appear to require any other technical features. However, the claim appears to further attempt to define the physical apparatus by two desirable results achieved during its operation. Namely that:

i) the electrons are deflected by the magnetic field from the magnet in a way that a force acts between the magnetic field from the magnet and a magnetic field from the electrons, and

ii) that kinetic energy is transferred between the apparatus and the electrons, which is construed to (implicitly) cause said generation of a force alluded to in the preamble of the claim.

18 When considering the claim in view of accompanying description and drawings, it appears that claim 1 is envisaged to require provision of a magnet juxtaposed to the chamber (as opposing to e.g. being provided annularly around the chamber). Magnetic fields and electric fields are interrelated and are both components of the electromagnetic force. It is common general knowledge that a moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to the magnetic field.

19 I note that several parts of the description appear to cast doubt on claim 1 requiring that deceleration or acceleration of electrons is necessary for creating a force on the magnet in either direction. For example, page 4 lines 1-8 appears to suggest that this is merely optional, rather than essential. This appears to be a drafting issue. Therefore, for the purposes of reaching this decision, I have construed it to be an essential requirement of claim 1 that the magnetic field from a magnet must be orientated in the cavity such so as to decelerate the electrons as they move from the cathode to the anode.

20 The description, on page 10, lines 4-10, states that a created vortex of electrons will create a magnetic field that repels the magnetic field emanating from the juxtaposed magnet, acting to push the magnet and the vortex of electrons apart. Both uses of a bar magnet and an electromagnet are envisaged as alternatives, see page 27 line 30 for example. The induced electromotive force (emf) is described to slow down the electrons orbiting in the vortex (as noted on page 10, lines 20-21 for example). Page 11 continues to explain that the vortex of electrons is stationary in space, as it is being diminished and replenished at a new position in space as electrons are emitted from the cathode and into the vortex before the crash into the housing 103 (i.e. into the anode). Electrons reaching the anode return to cathode via a completed electrical circuit. In other words, claim 1 is construed to require an isolated system.'

- Mr Klemz had no criticism of any of those paragraphs of the Decision save for the final sentence. He said that the invention is not an isolated system. He explained that the system is connected to an external power supply. Mr Klemz agreed, however, that the apparatus is isolated from a mechanical perspective in that it accelerates in thrust mode without any external force acting on the apparatus. Likewise, in damper mode the apparatus is moving, possibly due to external forces, but the force of claim 1 causing the apparatus to decelerate is generated internally without any contribution from an external force.

- The exclusion of the action of an external force of course also excludes a force caused by, and in reaction to, an expulsive force from the apparatus to the exterior.

The law

- I was referred to one authority, the judgment of Floyd J in Blacklight Power Inc. v The Comptroller-General of Patents [2008] EWHC 2763 (Pat). It was an appeal from a decision of a Hearing Officer in which he had rejected two patent applications. One related to a plasma reactor which generates power and a new hydrogen species named 'the hydrino' by the inventor. The other application related to a laser which operates using the hydrino. The claimed existence of the hydrino was part of what the inventor called his 'Grand Unifying Theory of Classical Quantum Mechanics' or 'GUTCQM'. The applications were rejected on the ground that the hydrino as proposed was contrary to generally accepted physical laws and consequently the inventions claimed were neither capable of industrial application nor did they comply with the requirement of sufficiency under the Act.

- Floyd J reviewed the statutory framework and authorities on appeals from the Comptroller:

'[34] I think that the effect of these authorities is as follows. It is not the law that any doubt, however small, on an issue of fact would force the Comptroller to allow the application to proceed to grant. Rather he should examine the material before him and attempt to come to a conclusion on the balance of probabilities. If he considers that there is a substantial doubt about an issue of fact which could lead to patentability at that stage, he should consider whether there is a reasonable prospect that matters will turn out differently if the matter is fully investigated at a trial. If so he should allow the application to proceed.

[35] I think this approach to the consideration of objections to patentability is in accordance with the statutory framework. The examiner will first raise an objection and put it to the applicant. The applicant then has an opportunity of persuading the Comptroller that his basis for considering that the objection applies is not sound. If the applicant does not persuade him to withdraw the objection he may refuse the application (section 18(3)). But at that stage he should consider whether, because there is a substantial doubt about an issue of fact, there is a reasonable prospect that matters may turn out differently at a trial, when there will be a full exploration of the matter with the benefit of expert evidence. If there is such a reasonable prospect he should allow the matter to proceed to grant. It goes without saying that mere optimism and a reasonable prospect of matters turning out differently are not the same thing. The reasonable prospect must be based on credible material before the Office. Macawberism, here as elsewhere, does not provide any basis for supposing that anything helpful will turn up. Moreover the greater has been the opportunity for the applicant to produce such material at the application stage, the smaller scope there is for supposing that giving him the benefit of the doubt will lead to a different conclusion.'

- Floyd J also considered the UKIPO Work Manual and the EPO Guidelines for Examination and found that the approach he had stated was consistent with them.

- The Hearing Officer had reached his decision solely on the balance of probabilities. Floyd J ruled that he had therefore applied the wrong test. However, the Hearing Officer had had enough information to decide the matter using the correct test.

- The Hearing Officer had found that (a) he was not in a position to assess whether GUTCQM was consistent with theories which it did not displace, (b) he was not well placed to assess how convincing the experimental material relied upon by the applicant was, and (c) the most important criterion in reaching a decision was therefore the extent to which the theory had been accepted by the scientific community. He had found that no support had been found for the theory.

- Floyd J considered whether the Hearing Officer would have allowed the application if he had applied the correct test:

'[47] Had the matter gone no further than the first two of the Hearing officer's criteria, it could be said that he was recognising there was a debatable underlying question of fact on which it could not be said that the applicant had no reasonable prospect of success. But his question concerning acceptance of the theory by the scientific community, was nevertheless a reasonable, and in the circumstances practical question to ask. Certainly, the absence of either widespread discussion or acceptance in the scientific literature or other media was a factor he was entitled to take into account. Such a question is an indirect way of approaching the underlying theory and physical phenomena. Does the absence of any real discussion or acceptance (or indeed practical demonstration) of GUTCQM mean that one can conclude now that there is no reasonable chance that the applicant would be able to establish his position at trial?

[48] It is clear that the Hearing Officer was alive to the danger of refusing an application in circumstances where the refusal depends on a disputed theory which may subsequently turn out to be correct: see the passage I have cited from [23] in the decision. In considering criterion (c) he was also alive to the fact that GUTCQM had been around for many years without evidence emerging as to its validity. That fact alone might be thought to make it unreasonable to suppose that the position would be different at a trial, particularly where, as here, the applicant had no reason which the Hearing Officer found plausible for explaining the absence of discussion or acceptance. There was certainly material before him on which he could have gone on to address, and decide, the question of whether there was any reasonable prospect that, on a fuller investigation, evidence would emerge which would support GUTCQM as a valid theory on the balance of probabilities. It would have been entirely fair for him to address and decide that question, given that the applicant had been given every opportunity to provide evidence is support of his theory.'

- Thus, although the Hearing Officer could have decided to refuse the application on the evidence before him, he did not. Floyd J decided that it was not open to him on the appeal to do so. There were two barriers, one procedural and one evidential. First, there had been no respondent's notice and therefore the appeal had been argued on behalf of the Comptroller solely on the basis that the reasoning of the Hearing Officer had been correct. Secondly, the evidence on whether there was a reasonable prospect that the GUTCQM theory could be accepted as a valid theory on fuller investigation was not before the court in the appeal.

- Floyd J therefore remitted the matter to be reconsidered by the Hearing Officer, applying the correct test in law to the evidence filed.

- In summary, the following are the principles of law relevant to the present case:

(1) When assessing whether a patent application should be refused under s.18(3) of the Act:

(a) The Office should examine the material filed and assess whether the invention is patentable on the balance of probabilities. If yes, the application should be allowed to go forward to grant.

(b) If no, the Office should consider whether there is a substantial doubt about an issue of fact which could lead to patentability. If no, the application should be refused.

(c) If yes, the Office should consider whether there is a reasonable prospect that the invention will be found patentable if that issue of fact is fully investigated at a trial. The application should be allowed only if the answer is yes.

(2) The reasonable prospect must be based on credible material before the Office and not on supposing that something helpful may turn up.

(3) The greater has been the opportunity for the applicant to produce such material, the smaller scope there is for supposing that fuller investigation will lead to a different conclusion.

(4) Matters which may be taken into account in resolving the issues under paragraph (1) include whether there has been authoritative independent comment on the invention, the nature of any such comment and in the absence of comment any plausible reasons for the absence.

The Decision

Lack of industrial application

- The Hearing Officer said that it is a settled matter in law that systems which are alleged to operate in a manner that is clearly contrary to well-established physical laws are regarded as not having any industrial application. She referred to Eastman Kodak Co. v American Photo Booths Inc., BL O/457/02 and Robinson's Application, BL O/336/08.

- The Hearing Officer noted that the Examiner (Dr Joanna Waldie) had found that the generation of the force the apparatus according to claim 1 is contrary to the principle of conservation of momentum. According to this principle, momentum is neither created nor destroyed but only changed through the action of forces as described by Newton's laws of motion. It is closely related to those laws, of which the first and third are of particular relevance. They are:

(1) A body continues in a state of rest or uniform motion in a straight line unless it is acted upon by external forces.

(3) If one body exerts a force on another, there is an equal and opposite force, a reaction, exerted on the first body by the second.

- The Hearing Officer recorded the reasoning by the Examiner. She had said that the Application proposes:

'23. … a mechanism by which kinetic energy and momentum are transferred between the magnet/housing of the apparatus and the electrons emitted by the cathode. All the electrons emitted by the cathode eventually reach the anode. Therefore, any momentum that has been transferred from the magnet/housing to the electrons will be transferred back to the housing when the electrons reach the anode. In this way, the total momentum of the apparatus does not change, and the apparatus will not be accelerated or decelerated. The examiner has argued that momentum lost by the electrons as they decelerate around the axis of the cavity (i.e. the cathode) cannot be equal to the change in the momentum of the housing moving along the same axis because these two momenta act in different directions.'

- The Hearing Officer then noted that the Examiner had found that the claimed invention operates in a manner which violates Newton's third law:

'24 … the application does not describe any way in which the apparatus could exert a force on something external to itself. Page 10 of the description as filed explains how there is a force between the magnetic field of the magnet and the magnetic field due to the motion of the electrons emitted by the cathode. Newton's third law requires that the force exerted on the magnet by the electrons is equal and opposite to the force exerted on the electrons by the magnet. However, the electrons are contained within the apparatus itself, and will eventually reach the anode, where they will exert a force on the anode and the anode will exert an equal and opposite force back on the electrons (to decelerate them). The force exerted on the magnet by the magnetic field of the electron motion will be balanced by the force exerted on the anode by the electrons crashing into the anode, so there will be no net force exerted on the apparatus by the electrons.'

- The Hearing Officer set out Mr Klemz's response to this:

'25 … Starting with Maxwell's equations, he claims the apparatus exploits the laws of classical electricity and magnetism to surf a travelling transverse pressure wave in the electromagnetic field, so it works by directing and manipulating the electromagnetic field, to create a force in a direction. Specifically, Mr Kelmz [sic] alleges that the magnetic field acts to decelerate the electrons, and this results in acceleration of the device. Working as a thruster, it is alleged to create a transverse pressure gradient, which causes the magnet to be repelled away from the electrons emitted by the cathode, which in turn is what is alleged to create the force suitable for e.g. propelling a vehicle.

26 According to Mr Klemz, at the 2nd paragraph of page 12 of his skeleton arguments, all electromagnetic and mechanical momentum is conserved and accounted for. Momentum lost by the electrons as they decelerate around the axis is equal to the momentum gained by the housing as it accelerates along the axis. The device is mechanically sealed, but electromagnetically and thermodynamically the device is open as charge flows into the cavity via the cathode and flows out via the anode. Energy enters the cavity via the electric field between cathode and anode and exits via an antenna as radio waves and as waste heat. The electrons in the cavity are effectively in free space and at the instant they are emitted from the cathode they have a velocity of zero, so all of the energy and momentum they gain is from the force due to the electric field and they transfer this momentum to the housing via the magnetic field of the bar magnet via covariant electromotive (emf) and magnetomotive (mmf) forces as described by Faraday's law and Lenz's law.'

- The Maxwell equations are a set of differential equations describing the space and time dependence of the electromagnetic field and forming the basis of classical electrodynamics. Faraday propounded several laws but I think the one that Mr Klemz had in mind is that an emf is induced in a conductor when the magnetic field surrounding it changes. Lenz's law is that the direction of an induced emf is always in opposition to the change that causes it.

- The Hearing Officer did not say in the section of her Decision on industrial application that she accepted the Examiner's view that the invention in operation would be inconsistent with the principle of conservation of momentum or Newton's third law. In the brief section on insufficiency she implied that she did. At the hearing of the appeal Mr Klemz and counsel for the Comptroller both assumed that she agreed with the Examiner on this and that it was a reason for her finding that the claimed invention lacks industrial application.

The experiments

- The Hearing Officer discussed the experiments Mr Klemz relied on, which were recorded on a video watched by the Hearing Officer:

'28 … In these experiments a prototype apparatus is suspended by a fishing line from a bicycle maintenance stand. Movement of the apparatus in these experiments was measured by shining a laser beam on to a mirror attached to the suspended apparatus and observing a laser dot produced by the reflected beam on a target screen. Movement of the laser dot across the screen indicates movement of the device itself.

29 … During the hearing Mr Klemz showed videos of the experiments he has conducted using the prototype apparatus. These videos show a laser dot traversing across a screen. They do not show what is happening to the prototype apparatus concurrent to the laser dot moving across the screen. …

30 In one of the experiments shown in a video recording called "static thrust", after the device is switched on, a small and gradual displacement of a laser dot can be observed over a short period of time, although the dot appears to vibrate during the course of said gradual overall displacement. As the video was played during the hearing, Mr Klemz remarked that the device is trying to push the pendulum uphill. At a certain point, displacement of the laser dot appears to be ceasing, which is when the applicant has further remarked during the hearing that the device comes to a halt, because the restorative force equals the thrust from the device. After the equipment was switched off, the laser dot does not appear to return to its original position.

31 To my mind, the fact that the laser dot does not appear to return [to] its start position appears to be contrary to what should be expected in a situation where a thrust is exerted on a suspended body, and then subsequently removed. In particular, if the device is suspended by a line, and a force acts to displace it sideways (upwards) like a pendulum - then the device should tend to swing back towards the neutral (bottommost) position when the thrust force is removed.'

- The Hearing Officer was not convinced that the experiments had proved anything conclusive:

'33 It is difficult to assess whether thrust is generated in the way the applicant describes based on the evidence provided in the video showing the laser dot alone, i.e. without a full and detailed view and analysis of the overall apparatus itself, e.g. from a concurrent second video showing the apparatus itself. I am of the view that the reason for displacement of the laser dot (and the device) is likely, if fully investigated at a trial with the benefit of expert evidence, to turn out to be due to reasons other than a thrust force. Potential other sources of the observed movement could include vibration of the device, a draft in the room, air convection, thermal expansion, non-recoverable deformation of test equipment part(s) due to heating.'

- The Hearing Officer concluded that according to the principles set out in Blacklight Power, the invention claimed lacked industrial application:

'34 Having considered the specification as originally filed, as well as the reasoning provided by the applicant during their follow-up correspondence, and during the hearing, I understand why the provided evidence may be considered to provide grounds for optimism that the invention may potentially be able to generate a force useful for industrial application. However, I am of the view that the conditions in which the experiments were conducted leave large margins for experimental uncertainties.

35 As noted above in paragraph 15 referring to Blacklight Power, mere optimism and a reasonable prospect of matters turning out differently are not the same thing. Considering the issue on the balance of probabilities, I am of the view that the evidence provided by the applicant does not give rise to a reasonable prospect that the applicant's theory might turn out to be valid if it were to be fully investigated at a trial with the benefit of expert evidence. Therefore, the claimed invention is considered to lack industrial application.'

- Finally, the Hearing Officer stated that if a claimed invention contradicts the law of physics as they are currently understood, the application will not teach the skilled reader clearly and completely enough how to work the invention. The Application was also refused for insufficiency.

The Grounds of Appeal

- There are nine grounds of appeal:

(1) The Examiner failed to understand the invention and mischaracterised it in her examination report. She therefore wrongly cited Blacklight Power Inc v The Comptroller-General of Patents [2008] EWHC 2763 (Pat) as relevant to this case.

(2) The Hearing Officer wrongly accepted Dr Waldie's mischaracterisation at face value and also the relevance of Blacklight Power.

(3) In Dr Waldie's examination report of 31 August 2023 Dr Waldie said 'I do not think that further discussions between you and myself are likely to change my assessment that your application does not meet the requirements of the Patents Act. Mr Klemz took this as a refusal to engage in a meaningful conversation and that it had deprived him of the chance to demonstrate the invention and disprove the conclusion reached by Dr Waldie.

(4) Dr Waldie was inexperienced and did not have the correct background in electromagnetism to enable her to understand the invention.

(5) The invention has two modes: an apparatus which generates a thrust, or alternatively a damper, force. The Hearing Officer had raised no objection in relation to the invention working as a damper. The two modes are symmetrical in that they rely on the same principles so her Decision lacked logic. Alternatively, the Application should at least have been allowed in relation to the apparatus in damper mode. The Hearing Officer had been shown a video of a prototype of the invention exhibiting damping behaviour which by itself established that a patent should be granted.

(6) The invention's operation as a damper is something any person skilled in the art should be able to understand and such a person who follows the instructions in the Application to build a prototype would be able to do so and to measure the damping behaviour.

(7) As the Hearing Officer raised no objection to the operation of the invention as a damper, it is reasonable to assume that if the Application had been written only to claim the apparatus as damper, it would have been granted.

(8) The operation of the invention as a thruster is much harder to understand because it is counter-intuitive.

(9) The Application deserves re-examination by a different examiner and Mr Klemz should have the chance to demonstrate the prototype in person.

- At the hearing I suggested to Mr Klemz that his grounds could be split into two substantive and procedural heads. The substantive grounds were first, the Hearing Officer had not understood the invention for the reasons given by Mr Klemz (grounds 1 and 2) and secondly, the Hearing Officer had raised no objections to the invention as a damper, from which it followed that there should have been no objection to the invention in thrust mode or, alternatively, a patent should have been granted for the invention as a damper (grounds 5, 6 and 7). The procedural grounds were that the Examiner had been inexperienced, had failed to continue discussions with Mr Klemz and had denied him the opportunity to demonstrate a prototype (grounds 5, 6 and 7). I suggested that grounds 8 and 9 were better characterized as wrap-up paragraphs ending with a request for re-examination.

- Having set out Mr Klemz's grounds in that way to help focus discussion at the hearing, I asked Mr Klemz whether he thought that this was a fair summary of his position. He said that it was.

The arguments

- Mr Klemz's endorsed what is said in the specification of the Application and the points he evidently made before the Examiner and the Hearing Officer.

- I put two simple examples to Mr Klemz in relation to the points made by the Examiner about conservation of momentum and Newton's third law. In both the apparatus is taken to be located in space. As the Hearing Officer noted, the Application indicates that the primary purpose of the invention would be to propel a spacecraft. Mr Klemz confirmed that if the apparatus was motionless, the invention in thrust mode would cause it to move without the application of any external force. If the apparatus was moving at a constant velocity, the invention in damper mode would cause it to decelerate, again without the application of any external force.

- Mr Klemz explained that these results were only surprising if the invention is looked at solely from a Newtonian mechanical viewpoint. They were fully consistent with the established laws of electromagnetism. He added that in fact one of the reasons it had taken him four years to conceive of the invention was that like everyone else he tended to be blinkered by the familiar Newtonian perspective.

- I asked Mr Klemz whether he was aware of any widely accepted statement that had been published pointing out that the laws of electromagnetism revealed by the nineteenth century giants such as Faraday, Maxwell and Lenz were inconsistent with Newton's earlier laws of motion or the principle of conservation of momentum. Mr Klemz did not say that he was aware of any such publication.

- Although neither Mr Klemz nor the Hearing Officer (nor the Examiner) thought it merited attention, I should note that the Application includes this:

'In operation, the momentum and kinetic energy from the electrons as they are slowed down is transferred to the bar magnet and the housing and so in this way, momentum and energy are conserved. Newton's third law is also met, by the action force (repulsive force between the vortex and the bar magnet, pushing the bar magnet and housing forward) having an equal reaction force (induced emf slowing down the electrons in the vortex). Due to Faraday's law and Lenz's law, the action and reaction forces are in fact perpendicular to each other.'

- This does not seem to me to meet the points made by the Examiner regarding the conservation of momentum and Newton's third law, points with which I agree. The Application here is apparently considering the conservation of momentum and the third law as between objects within the apparatus. It does not address those principles in relation to the momentum of the apparatus as whole or the application of an external force to the apparatus. Regarding the final sentence, I also observe that Newton's third law states that the action and reaction are equal and opposite.

- I told Mr Klemz of my impression that his invention, if accepted, would surely have created a major impression in the scientific world. Mr Klemz agreed. He said that he expected his invention to be massively disruptive, giving two examples. Satellites would have an infinite energy source rather than a finite life ending when propellant ran out. Secondly, it would be possible to bring orbiting objects back to earth if no longer required rather than having them form an increasing amount of space junk.

- Despite this, Mr Klemz was unable to present any reference to his invention in a science journal or other publication since the Application was published in April 2021. He said that in June 2022 he had used Google to make a list of individuals at higher educational institutions specialising in this field and sent each of them an email summarising his invention. Mr Klemz could not remember how many such emails he said but it was dozens. Despite this, only one academic in Cardiff responded. Mr Klemz believed that his invention had been viewed with the usual Newtonian mindset.

- The response from Cardiff led to correspondence with the UK Space Agency in Swindon. Two letters were in evidence. The first, dated 18 December 2023, was from Helen Roberts, GSTP Programme Manager. (I believe that GSTP stands for general support technology programme). It was in response to a statement of interest submitted by Mr Klemz requesting support. I do not know what was in the statement of interest, but Ms Roberts was encouraging and said that an outline proposal should be submitted to the European Space Agency (ESA) by the end of January 2024.

- The second letter, also from Ms Roberts on behalf of the UK Space Agency, is dated 28 March 2024. Ms Roberts said that based on the recommendation from the ESA, Mr Klemz should resubmit his proposal through the Open Space Innovation Platform.

- Mr Klemz said that his application was archived by the ESA, citing the pre-hearing report of Dr Waldie dated 30 April 2024. That communication from ESA was not filed in evidence. No further action has been taken by the ESA. I am not able to take anything of significance from this correspondence.

- Counsel for the Comptroller submitted that no material had been filed by Mr Klemz and nothing had been said by him which raised any reasonable prospect that fuller investigation of the facts at a trial would result in a conclusion any different to that taken by the Hearing Officer.

- Counsel highlighted the Hearing Officer's findings with regard to the video experiments she had witnessed, using the movement of a laser dot to demonstrate motion caused by the working of the invention. In particular, although the alleged force created by the invention had been likened by Mr Klemz to the device trying to push a pendulum uphill, when the device was switched off, the laser dot did not move back to its original position.

- Counsel submitted that even if Mr Klemz's invention were to be shown to work, the information in the Application does not make it plausible that it will work and so the Application should be refused on that ground, raised in the respondent's notice.

- With regard to the procedural criticisms raised by Mr Klemz in his Grounds of Appeal, counsel said that Mr Klemz had been given a full opportunity to put his arguments before the Examiner. It had not been unreasonable for her to reach the view that a line had to be drawn ending the debate and for her to deliver her conclusion.

- The main point made by Mr Klemz in reply was in relation to the experiment. He said that the motion generated in the prototype was only in the order of 2mm. The stiffness of the power cables attached to the box was the likely explanation for the laser dot not returning to its start position when the prototype was turned off.

Discussion

- It seems to me to be clear, based on the written material before the court and my exchanges with Mr Klemz at the hearing, that the invention, if it were to work, would do so in a manner inconsistent with the principle of conservation of momentum, Newton's third law and for that matter Newton's first law.

- Having regard to all the written and oral evidence I take the view that on the balance of probabilities the invention lacks industrial application because of those inconsistencies. For the same reason the invention is not disclosed in the Application in a manner which is sufficiently clear and complete for it to be performed by a person skilled in the art.

- I do not say that there is no substantial doubt about an issue of fact related to the patentability of the invention. There is a mass of doubts. But the inconsistencies with the principle of conservation of momentum and Newton's laws are evident enough for me to conclude that even if relevant facts were to be explored at trial, and on the assumption that this could be done effectively, there is no reasonable prospect that the invention would be shown to be patentable.

- I am supported in that view by the lack of any evidence that even one expert in the field of electromagnetism and/or spaceship propulsion has shown any support for the theory behind the invention.

- As to Mr Klemz's criticisms of the conduct of the Examiner, in my view she cannot be criticised for deciding that further discussion with Mr Klemz was not going to progress matters. I am not satisfied that this decision was taken before it could reasonably have been.

- I also do not think that the Hearing Officer accepted without question the conclusions of the Examiner. The Decision quotes the Examiner's findings in sufficient detail for the Hearing Officer to have considered and accepted them. These were supplemented by further and consistent findings made solely by the Hearing Officer, particularly about the experiments, which the Examiner did not see.

- As to those experiments, Mr Klemz's reason given in answer to the Hearing Officer's cogent point that the laser dot did not return to its starting position when the device was switched off, was new, unconfirmed and not investigated at the time. None of this inspired confidence in the accuracy and reliability of the experiment. Still less can it be said that anything may be deduced from what was seen.

Conclusion

- It is always possible that I am wrong about the viability of the invention and that in due time Mr Klemz will be famously vindicated. If so, it appears that I am in the company of some dozens of expert academics in the field. I must apply the law. I have no real doubt that the Application should not go forward to grant.

- I have found no fault in the either the reasoning or the conclusion of the Hearing Officer. The appeal is dismissed.