MARTIN BOWDERY QC:

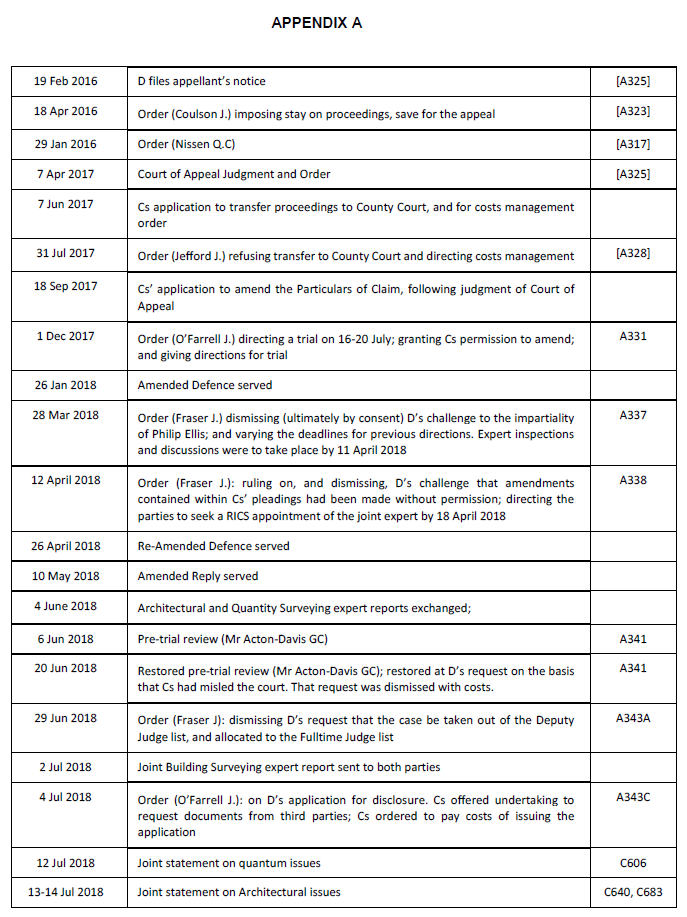

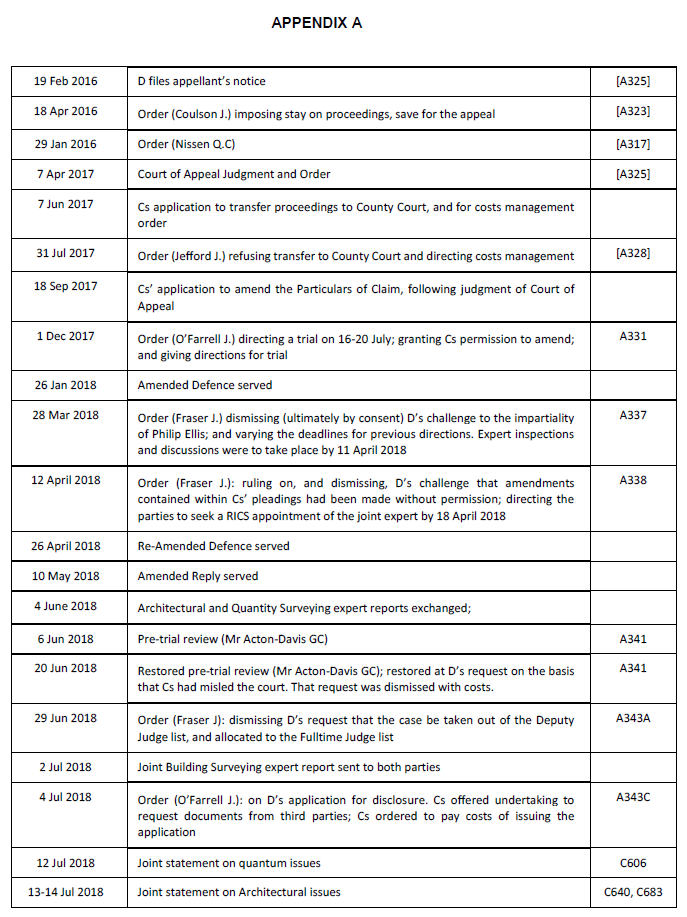

- I have read and heard thoughtful and thorough submissions on costs from Seb Oram, Counsel for the Claimants, and Louis Flannery QC, Senior Counsel for the Defendant. This is a post-judgment hearing to consider consequential matters arising out of the judgment which I handed down on the 26th November 2018. I have also been provided with a very helpful Chronology prepared by the Claimants (which I incorporate by reference into this judgment at Appendix A). I note that these proceeding have had the benefit of case management orders from some nine full-time and part-time TCC High Court Judges, if one includes the case management orders I made during the trial and the Order made by Mr Justice Waksman last week.

- The following issues require to be dealt with today:

(1) whether the Defendant is entitled to her costs on the indemnity basis;

(2) whether the Defendant is entitled to all of her pre-action costs;

(3) what (if any) interest should be ordered in respect of costs already paid by the Defendant;

(4) the amount of any payment on account.

The Defendant's approved cost budget following the CCMC before O'Farrell J was of the sum of approximately £415,000 excluding VAT. The Defendant's revised budget totals £724,265.63 excluding VAT and the costs of preparing the budget.

Costs that remain to be awarded

- By way of introduction, I should identify that two previous Orders have been made reserving costs: one on 29th January 2016, when Alexander Nissen QC reserved the costs of the preliminary issues trial; and secondly on 7th April 2017, when the Court of Appeal ordered that the Defendant appellant should pay one half of the costs of the appeal, the remaining half to be reserved to the Trial Judge. There have also been various Part 36 and "without prejudice save as to costs" offers.

- The best offers were as follows. On 26th March 2015, the Defendant made an offer under Part 36 of some £25,000. By comparison, the Claimants offered on 11th January 2018 to accept £45,000 on a Part 36 basis, and amended that offer on 22nd March 2018 to accept the same amount, but 60% of their costs on a Calderbank basis. The Claimants' previous offers were higher, reflecting the outcome of the preliminary issues trial. The Claimants accept that they failed to obtain a judgment more advantageous than the Defendant's Part 36 offer and, as a consequence, she is entitled to her costs after 16th April 2015 on the standard basis, and interest on those costs pursuant to CPR 36.17(3).

- There are three elements of the costs that remain to be awarded which are not covered by the matters described above. These are as follows:

1) 50% of the balance of the Court of Appeal costs;

2) the costs reserved by Alexander Nissen QC in respect of the costs of the preliminary issues; and

3) the costs of the proceedings prior to the expiry of the relevant period of Defendant's offer. As to the Court of Appeal costs, the Claimants accept that they should follow the event. Similarly, the Claimants accept that the costs reserved in respect of the preliminary issues trial should also follow the event.

- As to the Defendant's costs prior to 16th April 2015, these are principally the costs of the pre-action phase because the Defendant's Defence was only served on the 19th May 2015. Whilst the Claimants accept that they must pay the Defendant's costs prior to the 16th April 2015 in principle, a significant reduction it is said should be deducted to reflect the alleged failure of the Defendant to engage or comply with the pre-action protocol.

- The relevant principles to be applied are as follows. CPR 36.17 only regulates the order for costs after 16th April 2015, the expiry of the relevant period. Those incurred prior to that date are governed by the general principles of CPR 44.2.

"(1) The court has discretion as to –

(a) whether costs are payable by one party to another;

(b) the amount of those costs; and

(c) when they are to be paid.

(2) If the court decides to make an order about costs –

(a) the general rule is that the unsuccessful party will be ordered to pay the costs of the successful party; but

(b) the court may make a different order.

(3) The general rule does not apply to the following proceedings –

(a) proceedings in the Court of Appeal on an application or appeal made in connection with proceedings in the Family Division; or

(b) proceedings in the Court of Appeal from a judgment, direction, decision or order given or made in probate proceedings or family proceedings.

(4) In deciding what order (if any) to make about costs, the court will have regard to all the circumstances, including –

(a) the conduct of all the parties;

(b) whether a party has succeeded on part of its case, even if that party has not been wholly successful; and

(c) any admissible offer to settle made by a party which is drawn to the court's attention, and which is not an offer to which costs consequences under Part 36 apply.

(5) The conduct of the parties includes –

(a) conduct before, as well as during, the proceedings and in particular the extent to which the parties followed the Practice Direction – Pre-Action Conduct or any relevant pre-action protocol;

(b) whether it was reasonable for a party to raise, pursue or contest a particular allegation or issue;

(c) the manner in which a party has pursued or defended its case or a particular allegation or issue; and

(d) whether a claimant who has succeeded in the claim, in whole or in part, exaggerated its claim.

(6) The orders which the court may make under this rule include an order that a party must pay –

(a) a proportion of another party's costs;

(b) a stated amount in respect of another party's costs;

(c) costs from or until a certain date only;

(d) costs incurred before proceedings have begun;

(e) costs relating to particular steps taken in the proceedings;

(f) costs relating only to a distinct part of the proceedings; and

(g) interest on costs from or until a certain date, including a date before judgment.

(7) Before the court considers making an order under paragraph (6)(f), it will consider whether it is practicable to make an order under paragraph (6)(a) or (c) instead.

(8) Where the court orders a party to pay costs subject to detailed assessment, it will order that party to pay a reasonable sum on account of costs, unless there is good reason not to do so."

INDEMNITY COSTS

- I turn to the first matter which must be resolved today. The relevant principles relating to indemnity costs are dealt with in a number of cases. I will begin by referring to the observations of His Honour Judge Keyser QC in Kellie v. Wheatley & Lloyd Architects Limited [2014] EWHC 2886 (TCC). At paragraphs 18 and 19 of his Judgment, he helpfully summarises the applicable principles:

"18. In general terms, an award of costs on the indemnity basis is justified only if the paying party's conduct is morally reprehensible or unreasonable to a high degree, so that the case falls outside the norm. The applicable principles were set out at length by Tomlinson J in Three Rivers District Council v The Governor and Company of the Bank of England [2006] EWHC 816 (Comm), at [25], in a passage on which Mr Lixenberg relied (omitting the eighth point, which was formulated with particular regard to the Three Rivers litigation):

'(1) The court should have regard to all the circumstances of the case and the discretion to award indemnity costs is extremely wide.

(2) The critical requirement before an indemnity order can be made in the successful defendant's favour is that there must be some conduct or some circumstance which takes the case out of the norm.

(3) Insofar as the conduct of the unsuccessful claimant is relied on as a ground for ordering indemnity costs, the test is not conduct attracting moral condemnation, which is an a fortiori ground, but rather unreasonableness.

(4) The court can and should have regard to the conduct of an unsuccessful claimant during the proceedings, both before and during the trial, as well as whether it was reasonable for the claimant to raise and pursue particular allegations and the manner in which the claimant pursued its case and its allegations.

(5) Where a claim is speculative, weak, opportunistic or thin, a claimant who chooses to pursue it is taking a high risk and can expect to pay indemnity costs if it fails.

(6) A fortiori, where the claim includes allegations of dishonesty, let alone allegations of conduct meriting an award to the claimant of exemplary damages, and those allegations are pursued aggressively inter alia by hostile cross examination.

(7) Where the unsuccessful allegations are the subject of extensive publicity, especially where it has been courted by the unsuccessful claimant, that is a further ground.'

19. More recently, in Courtwell Properties Ltd v Greencore PF (UK) Ltd [2014] EWHC 184 (TCC), Akenhead J said this:

'22. So far as indemnity costs are concerned, there are numerous authorities which address the circumstances in which these may be ordered. A helpful if not absolutely exhaustive summary was given by Mr Justice Coulson in Elvanite Full Circle Ltd v AMEC Earth & Environmental (UK) Ltd [2013] EWHC (TCC):

'16. The principles relating to indemnity costs are rather better known. They can be summarised as follows:

(a) Indemnity costs are appropriate only where the conduct of a paying party is unreasonable "to a high degree. 'Unreasonable' in this context does not mean merely wrong or misguided in hindsight": see Simon Brown LJ (as he then was) in Kiam v MGN Ltd [2002] 1 WLR 2810.

(b) The court must therefore decide whether there is something in the conduct of the action, or the circumstances of the case in general, which takes it out of the norm in a way which justifies an order for indemnity costs: see Waller LJ in Excelsior Commercial and Industrial Holdings Ltd v Salisbury Hammer Aspden and Johnson [2002] EWCA (Civ) 879.

(c) The pursuit of a weak claim will not usually, on its own, justify an order for indemnity costs, provided that the claim was at least arguable. But the pursuit of a hopeless claim (or a claim which the party pursuing it should have realised was hopeless) may well lead to such an order: see, for example, Wates Construction Ltd v HGP Greentree Alchurch Evans Ltd [2006] BLR 45.

(d) If a claimant casts its claim disproportionately wide, and requires the defendant to meet such a claim, there was no injustice in denying the claimant the benefit of an assessment on a proportionate basis given that, in such circumstances, the claimant had forfeited its rights to the benefit of the doubt on reasonableness: see Digicel (St Lucia) Ltd v Cable and Wireless PLC [2010] EWHC 888 (Ch)."

To this can be added a number of other specific and general points:

(i) The discretion to award indemnity costs is a wide one and must be exercised taking into account all the circumstances and considering the matters complained of in the context of the overall litigation (see Three Rivers DC v the Governor of the Bank of England [2006] EWHC 816 (Comm) and Digicel (as above)).

(ii) Dishonesty or moral blame does not have to be established to justify indemnity costs (Reid Minty v Taylor [2002] WLR 2800).

(iii) The conduct of experts can justify an order for indemnity costs in respect of costs generated by them (see Williams v Jervis [2009] EWHC 1837 (QB).

(iv) A failure to comply with Pre-Action Protocol requirements could result in indemnity costs being awarded.

(v) A refusal to mediate or engage in mediation or some other alternative dispute resolution process could justify an award of indemnity costs.'"

- I also read and found helpful the observations of (as he then was) Coulson J in The Governors and Company of the Bank of Ireland & Anor v. Watts Group plc [2017] EWHC 2472 (TCC) in paragraphs 6, 7, 8 and 9:

"6. The relevant principles governing indemnity costs are set out in a number of cases. In Elvanite Full Circle Limited v Amec Earth and Environmental (UK) Limited [2013] EWHC 1643 (TCC) – a case with many similarities to the present case – I summarised those principles as follows:

'16. …

(a) Indemnity costs are appropriate only where the conduct of a paying party is unreasonable "to a high degree. 'Unreasonable' in this context does not mean merely wrong or misguided in hindsight": see Simon Brown LJ (as he then was) in Kiam v MGN Ltd [2002] 1 WLR 2810.

(b) The court must therefore decide whether there is something in the conduct of the action, or the circumstances of the case in general, which takes it out of the norm in a way which justifies an order for indemnity costs: see Waller LJ in Excelsior Commercial and Industrial Holdings Ltd v Salisbury Hammer Aspden and Johnson [2002] EWCA (Civ) 879.

(c) The pursuit of a weak claim will not usually, on its own, justify an order for indemnity costs, provided that the claim was at least arguable. But the pursuit of a hopeless claim (or a claim which the party pursuing it should have realised was hopeless) may well lead to such an order: see, for example, Wates Construction Ltd v HGP Greentree Alchurch Evans Ltd [2006] BLR 45.

(d) If a claimant casts its claim disproportionately wide, and requires the defendant to meet such a claim, there was no injustice in denying the claimant the benefit of an assessment on a proportionate basis given that, in such circumstances, the claimant had forfeited its rights to the benefit of the doubt on reasonableness: see Digicel (St Lucia) Ltd v Cable and Wireless PLC [2010] EWHC 888 (Ch).

17. These principles have recently been restated in the judgment of Gloster J (as she then was) in Euroption Strategic Fund Ltd v Skandinaviska Enskilda Banken AB [2012] EWHC 749 (Comm).'

7. With one partial exception, dealt with in paragraph 10 below, I do not regard this as a case in which an order for indemnity costs is justified or proportionate. In my view, this was not a claim which was or should have been regarded as hopeless from the outset. On the contrary, it was a case which was supported, at least in part, by expert evidence and the detailed witness statements of those involved in the relevant events at the Bank. Whilst it is true that there were always going to be questions about the lending arrangements, it would be wrong to conclude that those should always have been regarded by the Bank as insurmountable.

8. Furthermore, when considering the proper basis of the assessment of costs, the court must avoid the dangers of hindsight. It must be wary of the suggestion by the successful party, in this case Watts that, in truth, the result in the case was inevitable. Amongst other things, such an approach runs the risk of unfairly denigrating the presentation of the successful party's case at trial. This case is a good example of that. In my judgment, one of the important reasons for Watts' success in these proceedings was the excellence of Ms Stephens' cross-examination of the Bank's factual witnesses. The answers she elicited in her careful and well-prepared exchanges with them were decisive of the issues on lending, and I am sure they came as a shock to the Bank's lawyers. This was a case won at trial; it was not a foregone conclusion.

9. Of course, the fact that the Bank refused a number of offers which, with hindsight, they should have accepted, is a factor that the court must consider when deciding on the appropriate basis of assessment. But, unlike a successful claimant (CPR 36.17(4)(b)), the fact that Watts beat the relevant offers does not give rise to an automatic entitlement to indemnity costs. I know this misalignment is considered by some to be unjustified, but it remains the law. Furthermore, I accept Mr Mitchell's submission that the fact that Watts made three offers, all in significant sums, indicates that Watts and/or their insurers took this claim seriously and considered that it had a commercial value. That also supports my conclusion that this was not an obviously hopeless case. So I am not persuaded that the Bank's failure to beat the offers justifies an order for indemnity costs."

- I have also had the helpful guidance of Lord Justice David Richards in Whaleys (Bradford) Limited v. Garry Bennett [2017] EWCA Civ 2143 drawn to my attention, and again I take into account the observations of the Court of Appeal in that case, where it was explained:

"In my view, it was unfortunate that the judge used the word "exceptional" to describe the circumstances that may justify an order for indemnity costs. The formulation repeatedly used by this Court is "out of the norm", reflecting, as Waller LJ said in Esure Services Ltd v. Quarco [2009] EWCA Civ 595 at [25], "something outside the ordinary and reasonable conduct of proceedings". Whatever the precise linguistic analysis, "exceptional" is apt as a matter of ordinary usage to suggest a stricter test and is best avoided. Its use in this case gave rise to an arguable ground of appeal and while I am satisfied, particularly in the light of the submissions made to him, that the Judge was not applying a stricter test, for the future it would be preferable if Judges expressly used the test of "out of the norm" established by this court."

- The Defendant relies upon the following matters in support of her application for indemnity costs:

- Non-compliance with pre-action protocol

- Without prejudice and part 36 offers

Taking each matter in turn:

(1) Pre-action Conduct

- Somewhat surprisingly the parties have relied on some 4 further Witness Statements served after judgment had been handed down dealing with pre-action conduct, although I should emphasise that all the facts in the Witness Statements were contested and both parties made it clear that they did not want a trial within a trial and, in particular, neither party wanted me to make any findings as to what was said or not said at a meeting held in November 2013.

- By way of background, the Defendant's Fifth Witness Statement at paragraphs 7 and 8 makes it quite clear that the past five years of her life "have been shrouded with worry, extreme stress, and depression that has also affected everyone in my family, including my two children". She goes on to explain:

"7. However, it is important that some specific details are pointed out in order to understand the severe negative impact of the Claimants' conduct towards me and how it affected my professional and personal life, for instance:

7.1 My business, Linia Studio, which I incorporated in January 2014 (see BL 1/11). This was a business which I had hoped to expand, but was instead ruined by this litigation against me. There simply was no way I could market myself in my profession as a designer, or advance my new business in light of a pending high profile, professional negligence claim.

7.2 My professional and academic credentials: in 2014, I completed a course for foreign qualified architects looking to convert their degrees for the purpose of registration with the ARB. I completed the course, but I didn't submit the application to the ARB due to the allegations of negligence against me; it would have affected the opinion of the examiners and so my application would inevitably have been unsuccessful.

7.3 My reputation as a diligent, competent, and experienced architectural designer with experience abroad as well as in the UK was now tarnished by the allegations of negligence permanently associated with my name.

8. The past five years of my life have been shrouded with worry, extreme stress, and depression that has also affected everyone in my family, including my two children. Considering that my youngest child was not even ten years old when the dispute kicked off, a third of her childhood has been overshadowed by a lawsuit. I am acutely aware that there are far worse circumstances one can experience, but raising confident and well-balanced adolescents against the backdrop of an inexplicable personal and professional persecution was philosophically, for me, the most tragic consequence of this litigation."

- Again I take into account what was said in that Witness Statement and the correspondence the Claimants sent to their neighbours, and also the much contested issue as to who said what and who behaved well or badly at the meeting on 26th November 2013, where the Defendant alleges that the First Claimant accused her of:

"being responsible for everything in its entirety. He became extremely agitated, insulting me and making accusations. When I protested, he leaned forward at me aggressively before storming off whilst repeatedly calling me a liar at the top of his voice… [He] continued to threaten me, this time he made it very clear what his intentions were when he shouted, 'I will destroy you' and 'I will make sure you never trade again."

- What was said at that meeting and generally during the pre-action period is strongly contested. Neither party wants me to have a trial within a trial as to who said what and when, but I do recognise that when close friends fall out harsh words are often exchanged by one party or both parties. This dispute between former friends clearly became highly emotive and both the Claimants and the Defendant may regret what was said and how they behaved. From their conduct during the trial and, in particular, whilst being cross-examined, it is clear that the Claimants and the Defendant are all strong characters who are used to getting their own way and who will stand up and defend what rightly or wrongly they think is in their own best interests. Even taking at face value all of what the Defendant complains about, I do not think that this pre-action conduct was out of the norm, and I certainly do not consider it justifies an order for indemnity costs.

(2) Non-Compliance with the pre-action protocol

- The next factor is non-compliance with the pre-action protocol. This is a curious case in that submissions have been made by both the Claimants and the Defendant's Counsel that neither party complied with the pre-action protocol. It is alleged that important information was not provided by the Claimant's. It is alleged that the Claimants' solicitors were high-handed in not responding to the request for meetings and providing a detailed response to the letter of claim and looked into issuing proceedings to avoid an increase in Court fees. It is also suggested that the claim was made originally solely in contract, and that there was no claim in negligence standing concurrent with the claim in contract and, therefore, the Defendant was entitled to resist this claim on the basis that there was no contract. I do not accept that this claim was made only in contract with no concurrent duties in tort. The letter of claim said "contract and/or negligence" and the correspondence before proceedings were issued was discussing "assumption of responsibility". In the circumstances where neither party embraced the pre-action protocol with any enthusiasm, I do not think that the non-compliance with the pre-action protocol would justify an indemnity costs order. I asked if I could be shown any authority where non-compliance with this pre-action protocol has led to any reduction in costs or with indemnity costs being ordered, but no authority was cited to me. But I do not think that a failure to comply with pre-action protocol would have caused any of these costs to be avoided. The parties were entrenched in their respective positions. This was a case which with the benefit of hindsight and having had the benefit of seeing the parties' behaviour in court was a case from the outset which would have to go to trial before these issues between former friends could be resolved.

(3) Conduct of the Litigation

- The third factor said to justify an indemnity costs order is the Claimants' conduct of the litigation. What is alleged is that the Claimants' pleadings were confused; the plea of professional negligence was made without expert evidence; the global claim was always hopeless; disclosure was shambolic; privilege was asserted over non-privileged material; and the case on defects was pleaded in a haphazard and spray gun manner. I have looked at each of these matters, and whilst it is correct that this was a hard-fought case – hard fought on both sides – I do not think the pleadings were sufficiently confused to justify indemnity costs. Most of the complaints regarding the pleadings were complaints about amendments which were made in hotly contested applications, but despite those hotly contested applications leave was given for these amendments to the pleadings by extremely experienced specialist High Court Judges.

- With regard to pleading professional negligence without expert evidence, the way in which expert evidence has been dealt with in this trial in retrospect has been unfortunate, but the provision of expert evidence was micromanaged by a number of very experienced High Court Judges or Deputy High Court judges who have case managed this action over the course of its life. It was suggested that Mr Ellis, who is a quantity surveyor, was not suitably qualified to support any allegation of professional negligence. The Defendant is an architect registered in the Netherlands, she is not an architect registered in this country. However, I consider that Mr Ellis did have sufficient expertise to support these claims made against the Defendant. The requirement is that for a professional negligence claim it must supported by a relevant professional with the necessary expertise, but not necessarily an expert in precisely the same field. The allegations of breach of duty related to project management and contract administration in which Mr Ellis was plainly qualified, and the Defendant's criticisms ignore the procedural history by which the experts were appointed.

- The second complaint is that the expert evidence to support the defects claim has always been lacking. Again, this ignores the timing and sequence of the Court's directions for expert evidence. The directions for expert evidence seem to have gone awry when the preliminary issue was ordered in July 2015. The Judge ordered that the Claimants could rely upon an architect/surveyor. As a consequence, the Claimants were not, at that stage, given permission to obtain expert evidence from an architect, as the expert evidence at that stage was limited to those matters relevant to the preliminary issue. When permission was ultimately given in December 2017 (after the case had gone to, and returned from, the Court of Appeal), the Claimants could no longer rely on Mr Ellis for all issues of liability, and for reasons of proportionality a joint expert was appointed to give opinions on the existence of defects, and all remaining issues of liability were to be dealt with by architectural experts. Unfortunately, the Experts' Reports were significantly delayed for a variety of reasons, to the extent that the architect/quantum reports were exchanged on 4th June 2018 (two days before the pre-trial review), the Joint Report on the existence of defects came significantly later on 2nd July (a matter of days before the trial started on 16th July), and Joint Statements were finalised between 12th and 14th July 2018. In those circumstances, I do not think that the parties could be blamed for the late provision of that expert evidence, which still in part supported the claims, and certainly did not say the whole entirety of the claim was hopeless. Yes in retrospect it may have assisted the parties if the architect and the quantity surveying experts had been appointed at a much earlier stage in the litigation. However, that, no doubt for good reasons at the time, was not ordered.

- The global claim is also criticised. Whilst I found it had many weaknesses and offended common sense, this claim was introduced by way of amendment and there was no application to strike it out. This was not a claim that was hopeless from the beginning; it was a claim which had to be considered at trial and dealt with at trial.

- In terms of the alleged shambolic disclosure, the disclosure may have come in "dribs and drabs", as is submitted by the Defendant's written submissions. In particular many photographs were not disclosed until April or May 2018 which should have been disclosed much earlier, but that is not a ground for ordering indemnity costs. If there was late disclosure, perhaps there should have been applications for unless orders, but none of that late disclosure would have an impact on whether this case would go to trial or not. Earlier disclosure of the photographs, which were helpful at trial, would not have led the Claimants to have abandoned the trial.

- Disputes as to whether meetings or documents were privileged or not has been a vexed question, particularly in relation to the costs hearing, but again I do not think that that justifies indemnity costs. This issue regarding the meeting on the 26th November 2013 was raised and decided by Mr Justice Waksman last week. The case on defects again was pleaded in a haphazard and spray gun manner, as is alleged by the Defendant's Counsel, but this was a schedule which had to be dealt with, it was a schedule which had to be addressed at trial by both sides' experts, and it was a matter on which I had to make findings. It may be correct that an excessive amount of time was devoted to the bollard, but it is unquestionable that the bollard was damaged, and it was open to the parties to debate who is responsible for that damage.

- With regard to the unmeritorious claims, whereas I am critical in the judgment of elements of the Claimants' case, that was after I had heard the evidence. These were not comments I was in a position to make before I heard the evidence. I consider this was a case, as Coulson J said in the Bank of Ireland trial, that was won at trial; it was not a foregone conclusion. The evidence had to be heard, the evidence had to be tested and a judgment had to be given. This is particularly the case in the light of the Court of Appeal's observations that the factual involvement of the Defendant in this garden project had to be tested at trial. As Lord Justice Hamblen explains at paragraph 91 of his Judgment:

"91. The importance of what Mrs Lejonvarn did to the nature and extent of the duty of care which she owed means that caution is necessary in seeking to define that duty in advance of a full consideration of the facts. Although the judge found that Mrs Lejonvarn did in fact perform the services identified in paragraph 14.1 and 14.3 to 14.6 of the particulars of claim he did not address the detail of what she did. That is no doubt because he was not concerned with the issue of or the evidence relating to breach. In my judgment no definitive statement of the nature and extent of the duty owed and of what that required can be made until the detailed facts have been considered and any description of the duty made at this stage needs to subject to that qualification."

This was very fact-sensitive case and this is why the evidence had to be heard at trial and findings had to be made.

- Stepping back and reviewing all these matters related to the Claimants' conduct of this litigation, I do not think that this conduct was out of the norm. This litigation was hard fought but much litigation in the TCC is hard fought. This was litigation between former friends who fell out somewhat dramatically. However, at all stages this litigation was closely and carefully case managed by experienced TCC Judges and I do not think the Claimants' conduct of this litigation can be said to be out of the norm.

(4) The without prejudice and Part 36 offers

- On the 26th March 2015, before she had served a Defence, the Defendant made an offer under Part 36 of some £25,000. The offer was not accepted. Part 36 is a comprehensive code as to how such offers should be treated, and indeed a comprehensive code that should be followed. It may be unfortunate where a Claimant beats a Defendant's offer they are entitled to indemnity costs, but where the Defendant does better than a Defendant's offer the Court does not award indemnity costs automatically. That is what has been prescribed by Part 36 and it is a code which I am obliged to follow.

- The Defendant's Senior Counsel, Louis Flannery QC, in his written submission stated:

"Somewhat scandalously, there is no provision in the CPR where a Defendant beating its offer gets any other benefit i.e. is entitled to his costs from 21 days from the offer as compared to the Claimant who beats its offer (indemnity costs as standard, uplift on costs, enhanced rate of interest etc.)"

These are the rules I must apply. However, as part of my general discretion, the fact that the Defendant did better than her offer made very early in these proceedings is an important matter which I should take into account as part of the exercise in judging whether the Defendant is entitled to indemnity costs.

- Therefore, stepping back and reviewing all the matters raised by the Defendant in her written and oral submissions, I do not think that in the exercise of my discretion as the Trial Judge and in the circumstances of this case an award for indemnity costs for the whole or part of her costs is appropriate. Applying, in particular, the principles set out by Coulson J (as he then was) in Elvanite Full Circle Limited v. Amec Earth and Environmental (UK) Limited [2013] EWHC 1643 (TCC):

"(a) Indemnity costs are appropriate only where the conduct of a paying party is unreasonable "to a high degree". 'Unreasonable' in this context does not mean merely wrong or misguided in hindsight": see Simon Brown LJ (as he then was) in Exam v MGN Ltd [2002] 1 WLR 2810.

(b) The court must therefore decide whether there is something in the conduct of the action, or the circumstances of the case in general, which takes it out of the norm in a way which justifies an order for indemnity costs: see Waller LJ in Excelsior Commercial and Industrial Holdings Ltd v Salisbury Hammer Aspden and Johnson [2002] EWCA (Civ) 879.

(c) The pursuit of a weak claim will not usually, on its own, justify an order for indemnity costs, provided that the claim was at least arguable. But the pursuit of a hopeless claim (or a claim which the party pursuing it should have realised was hopeless) may well lead to such an order: see, for example, Wates Construction Ltd v HOP Greentree Alchurch Evans Ltd [2006] BLR 45.

(d) If a claimant casts its claim disproportionately wide, and requires the defendant to meet such a claim, there was no injustice in denying the claimant the benefit of an assessment on a proportionate basis given that, in such circumstances, the claimant had forfeited its rights to the benefit of the doubt on reasonableness: see Digicel (St Lucia) Ltd v Cable and Wireless PLC [2010] EWHC 888 (Ch)."

I do not think the Defendant is entitled to an order for indemnity costs for the whole or part of her costs.

- The Claimants must now rue the day they rejected the Defendant's offer to settle but this was never an obviously hopeless case. But unlike a successful Claimant, the fact that the Defendant did better than her relevant offer does not give rise to an automatic entitlement to indemnity costs.

- Having considered all the matters raised and pursued by Senior Counsel on behalf of the Defendant, I do not consider that the Claimants' conduct of the action or the circumstances of the case including the Claimants' rejection of the Defendant's very early Part 36 Offer takes it out of the norm and justifies an order for indemnity costs for the whole or part of her costs. Therefore, costs will be ordered on a standard basis.

- There is then the question whether the Defendant is entitled to all of her pre-action costs because of the conduct of the Defendant prior to the claim form being issued. I have already addressed the pre-action protocol. I have already addressed the fact that I consider the claim for negligence was properly raised before the claim form was issued. If a meeting did not take place, meetings were offered to take place after the claim form had been issued, and in the circumstances where both sides are, in my opinion, justifiably critical of each other during the pre-action protocol process, I do not think that that behaviour which I have heard about and read in the correspondence exchanged between the parties' solicitors justifies any reduction of the costs which the Defendant incurred during the pre-action protocol. Yes, this was a case which was hard fought, yes some of the correspondence from both sides' solicitors was more aggressive than I would expect in light of the CPR, but it was not sufficient to justify any deduction in the recovery of the Defendant's costs.

- Regarding interest on costs already paid by the Defendant, 4% has been offered by the Claimants in their submissions. That is, 4% per annum above base rate from the date of payment. 8% is asked for by the Defendant. I consider 4% is above what is normally ordered in respect of interest on costs and, therefore, I order that interest on costs should be paid at 4% above base rate from the date of payment. It is suggested that no interest should be payable whilst this matter is being considered by the Court of Appeal. I do not think it is appropriate… Have you conceded that point? You have, have you not?

- MR FLANNERY: No, my Lord.

- MARTIN BOWDERY QC: Then I think interest should be paid on those costs incurred whilst this matter was being sent to the Court of Appeal. Permission to appeal was given. The appeal had to be heard. The appeal has assisted this Court enormously in terms of the judgment of Hamblen LJ directing what I must do when I consider the facts of this trial, and 4% above base rate from the date of payment will be ordered.

- In terms of the amount of any payment on account, the incurred costs, I am told, greatly exceed the costs budget, and at the moment – I will hear argument if I am wrong – my provisional view is that I order £200,000 on account, to be paid within the next 6 weeks.

- MR FLANNERY: My Lord, 80% of the defendant's costs budget was offered by the claimants, if your Lordship was against us, which exceeds £200,000.

- THE DEPUTY JUDGE: What is the costs budget?

- MR FLANNERY: £413,000. In other words, about £320,000. And that ignores the Court of Appeal costs that have also been included, my Lord. So we would ask for a total of £365,000.

- MR ORAM: I do not object. Within 6 weeks.

- THE DEPUTY JUDGE: That is very helpful. £365,000 within 6 weeks.

13th December 2018