The Law Commission

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> The Law Commission >> Electoral Law [2020] EWLC 398 (March 2020)

URL: https://www.bailii.org/ew/other/EWLC/2020/LC389.html

Cite as: [2020] EWLC 398

|

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback] [DONATE] | |

The Law Commission |

||

|

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> The Law Commission >> Electoral Law [2020] EWLC 398 (March 2020) URL: https://www.bailii.org/ew/other/EWLC/2020/LC389.html Cite as: [2020] EWLC 398 |

||

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

A joint final report

HC145 SG/2020/35

Law Com No 389 Scot Law Com No 256

Law Commission of England and Wales Law Commission No 389 Scottish Law Commission Scottish Law Commission No 256 |

Electoral Law A joint final report |

Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965 Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers Presented to the National Assembly for Wales Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 16 March 2020 |

HC 145 SG/2020/35 |

© Crown copyright 2020

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents.

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected]

ISBN 978-1-5286-1805-2 CCS0220205190 3/19

Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum

Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office

The Law Commission of England and Wales and the Scottish Law Commission were set up by the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law.

The Law Commissioners are:

The Right Honourable Lord Justice Green, Chair Professor Sarah Green

Professor Nick Hopkins Professor Penney Lewis Nicholas Paines QC

The Chief Executive of the Law Commission of England and Wales is Phil Golding.

The Law Commission is located at 1st Floor, Tower, 52 Queen Anne’s Gate, London, SW1H 9AG.

The Scottish Law Commissioners are:

The Right Honourable Lady Paton, Chair Kate Dowdalls QC

Professor Frankie McCarthy

The Chief Executive of the Scottish Law Commission is Malcolm McMillan.

The Scottish Law Commission is located at 140 Causewayside, Edinburgh, EH9 1PR.

The terms of the report were agreed on 27 February 2020.

The text of this report is available at http://www.lawcom.gov.uk/project/electoral-law

http://www.scotlawcom.gov.uk/publications/

Glossary of terms | page xi |

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION | 1 |

Outline of this report | 1 |

The stages of the project | 2 |

Terms of reference | 4 |

Elections and referendums within scope | 4 |

Law reform and policy | 5 |

Devolution and a tripartite reform project | 6 |

Acknowledgments | 7 |

CHAPTER 2: LEGISLATIVE FRAMEWORK | 8 |

Introduction | 8 |

How did electoral law become so complex? | 9 |

Rationalising fragmented legislation into a single consistent legislative framework governing all elections | 10 |

The balance between primary and secondary legislation | 10 |

Rationalising election law within the devolutionary framework | 13 |

Consultees’ views on devolution and rationalising electoral laws | 15 |

Devolution and our recommended legislative framework | 16 |

Conclusion on a rationalised electoral law framework Electoral laws should be consistent across elections, subject to differentiation due to the voting system or some other justifiable principle or policy | 16 17 |

Our specimen draft Standard Elections rules | 19 |

CHAPTER 3: MANAGEMENT AND OVERSIGHT | 21 |

Introduction | 21 |

Ceremonial and “acting” returning officers in england and wales | 21 |

Legislative framework for management and oversight of elections | 23 |

Powers of direction | 24 |

Cooperation between directing officers and local returning officers | 26 |

An example of powers of direction: our specimen drafting | 26 |

Administrative areas | 27 |

Designation and review of polling districts | 27 |

Appeals against designations of administrative areas | 28 |

CHAPTER 4: THE REGISTRATION OF ELECTORS 30

Introduction 30

Franchise 30

Residence 31

Special category electors 32

Registration generally 33

Simplifying and restating the provisions on maintaining and accessing

the register 34

Primary legislation should contain core registration principles 34

The deadline for registration 34

A single electoral register in law 35

Secondary legislation to contain detailed administrative rules on

registration 35

Our technical recommendations aimed at restating the law on

electoral registration 36

Specific problems in electoral registration 38

Making registration systems capable of exporting data to and

interacting with each other 38

EU citizens’ declaration of intent to vote in the UK 39

The issue of registration at a second residence 39

Acknowledging in legislation the possibility of satisfying the residence

test in more than one place 40

Should the law lay down factors to be considered by registration

officers when registering an elector at a second residence? 41

Should electors applying to be registered in respect of a second home

be required to make a declaration supporting their application? 43

Should electors be asked to designate, when registering at a second home, one residence as the one at which they will vote at national

elections? 44

CHAPTER 5: MANNER OF VOTING 46

Introduction 46

The secret ballot 46

Applying the secrecy provision in the modern context 47

Requiring secret documents to be stored securely 48

Qualified secrecy 49

Voter identification at the poll 51

Ballot paper design and content 51

Promoting access by voters with disabilities 53

CHAPTER 6: ABSENT VOTING 55

Introduction 55

Absent voting entitlement 55

Absent voting records 57

Restrictions on proxy voting 58

Administration of absent voter status 59

Special polling stations in Northern Ireland 59

The form of absent voter applications 60

Waiver of the requirement to provide a signature for postal vote

application forms 62

The postal voting process 63

The response to postal voting fraud 64

Regulating campaigners’ handling of postal votes 65

CHAPTER 7: NOTICE OF ELECTION AND NOMINATIONS 68

Introduction 68

The nomination paper 69

A single set of papers 69

Delivery of nomination papers 70

Adaptations for party lists 72

Subscribing to a nomination, not a paper 73

The role of the returning officer 74

The exception for disqualifications of serving prisoners 75

Commonly used names 76

Sham nominations 77

CHAPTER 8: THE POLLING PROCESS 81

Voter information and other public notices 81

Polling notices 81

Poll cards 82

The logistics of polling 83

Political neutrality of electoral administrators 83

Selection and control of polling stations 84

Equipment for the poll 85

The use of force 86

The polling procedure 87

Polling rules 87

Entitlement to vote and prescribed questions 88

Equal access for voters with disabilities 90

Voting with the assistance of a companion 90

The requirement to provide equipment 92

Events frustrating the poll 94

Death of a candidate 94

Emergencies 97

CHAPTER 9: THE COUNT AND DECLARATION OF THE RESULT 101

The classical polling rules 101

Standardising polling rules 102

Timing of the count 102

Representation at the count 104

Elections using the single transferable vote system 105

Electronic counting 107

Standardising the rules 107

Certification requirements 108

CHAPTER 10: TIMETABLES AND COMBINATION OF POLLS 110

Introduction 110

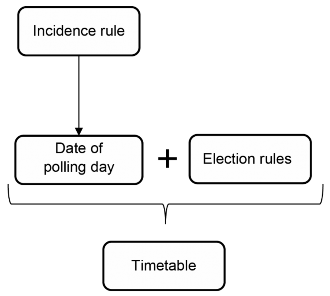

Electoral timetables 110

Incidence of elections 110

UK Parliamentary elections 110

Orientation of timetables 111

Re-orienting the UK Parliamentary election timetable 112

Timetable at UK Parliamentary by-elections 113

Electronic communication of the writ of election 114

Standardising the legislative timetable at UK elections 114

Length of elections timetables 116

Combination of polls 118

Combinability 119

Management of combinations 122

Combined conduct rules 123

CHAPTER 11: ELECTORAL OFFENCES 126

Introduction 126

The legislative framework for electoral offences 127

“Corrupt and illegal practices” 128

The electoral offences 129

The classical campaign corrupt practice offences: bribery, treating and

undue influence 129

Bribery and treating 129

Undue influence 131

Pressure, duress and trickery: our proposals in consultation 133

Abuse of influence: our consultation question 134

Intimidation 137

Deception 137

Improper pressure 137

Conclusion on improper pressure 139

Consent to prosecution 140

Imprinting online material 140

Other illegal practices targeting campaign conduct 143

Should the illegal practice of disturbing election meetings apply only to candidates and those supporting them, and no longer be predicated

on the “lawfulness” of the meeting? 143

Should the offence of falsely stating that another candidate has

withdrawn be retained? 144

Combating electoral malpractice 145

Intimidation of candidates and campaigners 146

CHAPTER 12: REGULATION OF CAMPAIGN EXPENDITURE 149

Core campaign regulation 149

Expense limits calculated by a formula 151

Simplifying the provisions on expenses returns 152

Location of election agents’ offices 154

Powers and sanctions for candidate expenses offences 154

New challenges in campaign regulation 156

Online campaigning 156

Notional expenditure and the responsibilities of election agents 158

CHAPTER 13: LEGAL CHALLENGE 160

Introduction 160

The grounds of challenge 161

The doctrine of “votes thrown away” 161

Positively stating the grounds for challenging an election in legislation 162

The role of agents 162

Parkinson v Lewis 163

Distinguishing between the civil and criminal aspects of corrupt and

illegal practices 164

Defects in nomination papers 166

How should disqualification affect the result of the election? 167

The procedure for bringing an election petition 168

A public interest petitioner? 171

Protective costs orders or protective expenses orders 172

Returning officers should have standing to bring petitions 173

Informal complaints 173

CHAPTER 14: REFERENDUMS 175

Introduction 175

Developments since the consultation paper 176

National referendums 176

The Referendums (Scotland) Act 2020 178

Our recommendations on the framework for conducting national

referendums 178

Local referendums 179

Legal framework 180

Legal challenge of local referendums 181

Neighbourhood planning referendums 181

Parish polls 182

Purpose of parish polls 182

Our recommendations 183

CHAPTER 15: RECOMMENDATIONS 185

The 1983 Act | The Representation of the People Act 1983. |

The 1985 Act | The Representation of the People Act 1985. |

Absent voting | Voting without personally attending at a polling station: either postal voting or voting by proxy. |

Additional member systems (AMS) | Systems of voting in which, in addition to candidates elected by the first past the post system, further members of the elected body are elected by a different voting system such as the party list. |

Candidate’s agent | The legislation generally requires a person to be appointed by a candidate to perform certain functions in connection with an election on the candidate’s behalf. Other persons acting in support of a particular candidate are also referred to as the candidate’s agents, and misconduct by such agents is capable of invalidating a candidate’s election. |

Assisted voting | Voting with the assistance of a companion, or that of the presiding officer. |

The canvass/ canvass form | The process of identifying people who are qualified to vote, for the purpose of entering them on the local electoral register. It normally involves sending a canvass form to each household in the area. |

The corresponding number list | A list supplied to a polling station. When ballot papers are issued to voters, the ballot paper number is entered on the list opposite the voter’s electoral register number. The list can be used if necessary for vote tracing. |

Chief Counting Officer | The person with overall responsibility to conduct a national referendum, and sometimes a local referendum. |

Chief Electoral Officer for Northern Ireland | The official who is the returning officer and electoral registration officer for all elections in Northern Ireland and is in charge of the Electoral Office for Northern Ireland. |

The classical rules | A term we use to refer to the set of rules governing Parliamentary and local government elections originating in the Victorian reforms of 1872 and 1883 and now found primarily in the Representation of the People Act 1983. |

An early general election | A term used in the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 to describe a general election occurring as a result of a vote in Parliament rather than at a fixed interval. |

Election-specific legislation | Legislation governing elections to a particular elected body or office. |

Electoral Commission | The independent statutory body that regulates political party and campaign finance in the United Kingdom, and sets standards and provides guidance on the administration of elections. The Commission is also tasked with administering national referendums. |

An election court | The court constituted to hear an election petition. |

Election petition | The legal process by which an election can be challenged before an election court. |

Electoral Management Board for Scotland | The body which has the general function of co-ordinating the administration of local government elections in Scotland, assisting local authorities and others in carrying out their functions and promoting best practice. |

First past the post | The traditional voting system in which the candidate who gains the most votes is elected. |

Franchise | The right of suffrage; the legal expression of who is eligible to vote. |

Greater London Authority (GLA) | The Greater London Authority consists of the Mayor of London and the 25 member London Assembly. The Mayor is elected using the supplementary vote system. There are two types of member of the London Assembly. Constituency members are elected by constituencies within London during the first past the post system. London members are elected on a London-wide basis using the party list system. |

xii

Household registration system | A term we use to describe the former process of registering voters on the basis of a completed canvass form. Household registration has been replaced in Great Britain by individual electoral registration, which has been in place in Northern Ireland since 2002. |

Individual electoral registration | The process of registering electors on the basis of an application to be registered made by each individual. |

The local government model | A term we use to describe those features of the classical rules that are specific to local government elections. |

The parliamentary model | A term we use to describe those features of the classical rules that are specific to UK Parliamentary elections. |

The party list system | A system of voting in which electors vote for lists of candidates presented by registered political parties as well as for independent (non-party) candidates. |

Voting in person | Voting in person at a polling station, rather than postal voting or voting by proxy. |

Judicial review | The process for legal challenge, before the High Court or in Scotland the Court of Session, of public and administrative acts and decisions. |

Poll clerks | Officials appointed by the returning officer to assist the presiding officer at a polling station. |

Polling district | Part of an electoral area served by a particular polling station. |

Polling place | An area or building within a polling district designated by the local authority as the area or place in which a polling station is to be set up. |

Polling station | The set of apparatus for voting in person, usually consisting principally of a table at which polling clerks mark the polling station register and issue ballot papers, booths in which voters can privately mark their ballot papers and a ballot box or boxes into which marked ballot papers are inserted. A room within a building can contain more than one polling station. |

Postal voting | Casting a vote on a ballot paper which is sent by post to the returning officer, accompanied by a postal voting statement; we refer to the postal voting statement and the ballot paper together as postal voting papers. Postal voting papers can also be handed in at a polling station. |

Postal voting statement | A declaration in a prescribed form that a person voting by post is entitled to cast the vote. |

Presiding officer | The official appointed by the returning officer to preside over a particular polling station. |

Primary legislation | Legislation contained in an Act of the UK Parliament, Scottish Parliament, Welsh Parliament, or Northern Ireland Assembly. |

Principal areas | The term used in legislation to refer to counties, districts, boroughs and county boroughs in England and Wales. |

Proxy voting | Casting a vote through a “proxy” appointed to cast the vote in person or by post on an elector’s behalf. |

Registered political party | A political party that is registered by the Electoral Commission under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000. |

Registration officer | An official of a local authority charged with maintaining a register of people residing in the local authority area, who are qualified to vote at elections held in the area. |

Returning officer | The official charged with conducting an election in a particular area and making a “return” of the result. Currently in England and Wales the returning officer for Parliamentary elections is a dignitary such as the sheriff of a county and most of the returning officer’s functions are discharged by an acting returning officer. |

Secondary legislation | Legislation in the form of Regulations made under law-making powers conferred (usually) upon the Secretary of State or Ministers. |

The single transferable vote (STV) | A voting system under which voters cast votes for more than one candidate, ranked in order of preference. The successful candidates are those whose vote reaches a 'quota' determined by the size of the electorate and the number of positions to be filled. The counting of voters proceeds in stages. At each stage the lowest scoring candidate is eliminated and votes cast for that candidate are transferred to the candidate marked next in order of preference on the ballot paper. Where a candidate’s vote reaches the quota at any stage, a proportion of the votes cast for that candidate are transferred to the candidate marked next in order of preference on the ballot paper. The process is repeated until all the seats are filled. |

The supplementary vote | A voting system under which voters cast a first and second preference vote; if no candidate secures more than half of the first preference votes, the second preference votes are taken into account. |

Tendered ballot paper or tendered vote | A ballot paper or vote cast by a voter who appears to have already voted in person or through a proxy or to be on the postal voting list. If the voter denies having voted or having applied for a postal vote, they must be issued with a ballot paper which is to be kept separately once marked. An election court can order the vote to be counted if satisfied it is valid. |

Verification | The process of reconciling the number of ballot papers received from a polling station at the count with the number of papers issued to the polling station in question. |

Vote tracing | Using the corresponding number list to trace the ballot paper issued to a particular voter. This can generally only be done by order of an election court where voting irregularities are suspected. |

Voting system | The system for identifying the successful candidate[s] on the basis of the votes cast; examples include first past the post, the party list system, the single transferable vote and the supplementary vote. |

Warrant for a writ of by-election | The step taken by the Speaker of the House of Commons to cause the Clerk of the Crown in Chancery to issue a writ of by-election to the returning officer. |

Writ of election or by-election | A Royal document communicating to the returning officer the calling of a general election or by-election. |

Electoral Law: a joint final report

To the Right Honourable Robert Buckland QC MP, Lord Chancellor and Secretary of State for Justice and the Scottish Ministers

This is the final report of the Law Commission of England and Wales and the Scottish Law Commission on electoral law in the UK. It follows a consultation paper published in December 2014 and an interim report published in February 2016.

As our interim report noted, the response to our consultation paper revealed considerable support and an urgent need for technical reform of electoral law. Such reform will streamline the rules governing the conduct of elections and challenges to them, removing inefficiencies and saving costs. Since the publication of our interim report calls for reform of electoral law have continued, including from the House of Commons Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee, which recently described the consolidation and simplification of electoral law as a “serious priority”.1

Electoral law in the UK has become complex, voluminous and fragmented. There is an enormous amount of primary and secondary2 legislative material governing elections and referendums. And yet, as we explain in chapter 2 of this report, a significant amount of that material repeats the classical law contained in the Representation of the People Acts 1983 and 2000. That includes some out of date and complex provisions which are in need of restating in more modern, simple language, or to take account of modern conditions and technology. In some cases, the law is very detailed in its prescription, while in others no statutory guidance is given on important questions such as whether a person resides for the purpose of electoral registration at two addresses, or when a returning officer may refuse a nomination paper which they think is a sham nomination.

The aims of the recommendations in this report are to ensure, first, that electoral laws are presented within a rational, modern legislative framework, governing all elections and referendums within its scope; and secondly, that provisions of electoral law are modern, simple, and fit for purpose. To that end we recommend a holistic legislative framework, split over primary and secondary legislation. That framework would avoid

1 Electoral law: the Urgent Need for Review, Report of the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee (2017-19) HC 244, p 5.

2 Our interim report cited 17 pieces of primary legislation and 27 pieces of secondary legislation, a number which has only increased since 2016. See Electoral Law: A Joint Interim Report (2016) Law Com; Scot Law Com; NI Law Com, p 5, available at http://www.lawcom.gov.uk/app/uploads/2016/02/electoral_law_interim_report.pdf.

the labyrinthine complexity that presents itself in the current law, by dealing together with legal norms that are shared across the electoral landscape, and drilling down into detail in secondary legislation. We recommend laws that reflect modern conditions, particularly in how electoral administrators hold registration and absent voting data.

These laws should be expressed in more accessible language, not least where they lay down electoral offences and describe the system for challenging elections.

This final report aims to provide a sufficient overview of electoral laws to enable the reader to understand our recommendations, along with the principal themes from the consultation which preceded the publication of our interim report. More detail can be found in our consultation paper and the supporting research papers, and our interim report.3 Our approach in this report has been to amend previous recommendations where developments since the publication of the interim report mean that the original recommendation is no longer appropriate. We have also amended some recommendations to make them clearer. We do not make any entirely new recommendations.

Chapter 2 considers the legislative framework governing elections, setting out our recommendations for rationalising the law governing elections and referendums. Subsequent chapters set out our recommendations in discrete areas of electoral law, namely: the management and oversight of elections (chapter 3); the registration of electors (chapter 4); the manner of voting (chapter 5); absent voting by post or proxy (chapter 6); the nomination of candidates (chapter 7); the polling process, including events which frustrate the poll (chapter 8); the count and determination of the result (chapter 9); election timetables and the combination of polls (chapter 10); electoral offences, including our recommendations for the reform of the offences of undue influence and the extension of the imprint requirements to online material (chapter 11); the regulation of campaign expenditure (chapter 12); legal challenge to elections (chapter 13); and national and local referendums, including parish polls (chapter 14).

The electoral law reform project was structured in three stages:

The scoping stage involved determining the scope of the reform project. A scoping consultation paper was published by the Law Commission of England and Wales on 15 June 2012, followed by a scoping report published on 11 December 2012. Following references from the UK Government to the Law Commissions of England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland, and from the Scottish Government to the Scottish Law Commission, the project moved to the next stage.

The second stage involved formulating proposals for reform of electoral law. These were set out in our consultation paper, published in December 2014.4 Our proposals attracted significant support from consultees and, given the

3 These can be found at https://www.lawcom.gov.uk/project/electoral-law/.

4 Electoral Law (2014) Law Commission Consultation Paper No 218; Scottish Law Commission Discussion Paper No 158; Northern Ireland Law Commission No 20, available at http://www.lawcom.gov.uk/app/uploads/2015/03/cp218_electoral_law.pdf.

weight and calibre of the responses, helped improve our proposals for reform. This stage concluded with the publication of an interim report, published in February 2016.

The final stage envisaged our publishing a final report and draft Bill to give effect to our final recommendations. Our interim report noted the continuing process of devolution, giving rise to a need for separate legislation by the devolved legislatures. We say more on this topic later in this chapter.

Following the publication of our interim report, the project entered a review period prescribed by our terms of reference, with a view to securing Government approval to progress to the third stage (which involved significant Bill drafting work). In due course, however, it became clear that work on exiting the European Union, and the accompanying unprecedented pressure on parliamentary business, meant that no comprehensive draft reform Bill would be introduced in the short term.

The Law Commission of England and Wales subsequently worked with the Cabinet Office, the Electoral Commission and the Association of Electoral Administrators (“AEA”) to consider alternative approaches to implement some of our recommendations. One approach which was eventually explored in some detail was to consider whether one or two statutory instruments could set out the conduct rules for electoral events presently governed by secondary legislation (which is all elections other than Parliamentary elections and local referendums). This was with a view to giving effect to some of our recommendations for reform, so far as that was possible using existing powers in primary legislation.

The exercise produced one advanced draft set of conduct rules governing three polls whose rules are subject to the affirmative resolution procedure for parliamentary approval, and included some work on a companion set of rules to be made by statutory instrument subject to the negative resolution procedure. It was decided in 2019, with the agreement of the Cabinet Office, that the priority should be to move on to producing the present final report. The drafts will be available to the Governments should they decide to pursue the production of standard elections rules as part of any implementation of this report.

This, our final report, contains our final recommendations to be laid before Parliament, the Scottish Parliament, and the National Assembly for Wales, soon to be renamed the Welsh Parliament or Senedd Cymru.5 It reflects, in places, on what has been learned through the work on drafting standard elections rules, and we occasionally refer to some of our specimen drafting to illustrate points made in this report. That specimen drafting is available on our website. We hope this will help readers to see for themselves what a single standard set of conduct rules governing multiple elections (and their combination with other electoral events) might look like.

5 Senedd and Elections (Wales) Act 2020, s 2. This report generally uses the new terminology.

We concluded following the scoping phase that this project should focus on the technical law governing elections and referendums, with a particular focus on electoral administration. We excluded from its scope subjects which had constitutional or political policy dimensions, such as reforming the franchise, voting systems or electoral boundaries. These conclusions are reflected in the terms of reference for this project, which are as follows:

To review the law relating to the conduct of elections and referendums in the UK, including challenges and associated criminal offences, but excluding:

fundamental change to the existing institutions concerned with electoral administration,

the franchise,

electoral boundaries,

the regulation of national campaigns, political parties, and broadcasts, and

voting systems.

This project is concerned with reforming the law governing all elections and referendums conducted under statute. There is a long list of types of elections within its scope, which currently includes:6

UK Parliamentary elections;

Scottish Parliamentary elections;

Welsh Parliamentary elections;

local government elections in England and Wales, including:

principal area local authority elections; and

parish, town and community council elections;

local government elections in Scotland,

Greater London Authority elections (to the London Assembly and of the London Mayor);

mayoral elections in England and Wales;

6 Elections to community councils, Health Boards, National Park Authorities and the Crofting Commission in Scotland are outside scope.

combined authority mayoral elections in England and Wales; and

Police and Crime Commissioner elections in England and Wales.

In addition, referendums are within the scope of the project if they are:

national referendums such as those held under the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000;

local referendums held under the Local Government Act 2000, the Local Government Finance Act 1992, or the Town and Country Planning Act 1990; or

parish polls.

Electoral law has continued to develop throughout the life of this project. This final report makes recommendations based on the current law, while taking account of impending changes.

The challenges faced by electoral law have also continued to evolve. These include regulating online advertising, disinformation and online intimidation. Many of these problems are not limited to electoral law, and are not properly within the scope of this report. Several have been considered by other bodies; by way of example, the Committee on Standards in Public Life published a report on the intimidation of those in public life, in particular candidates and campaigners in 2017.7 Some of the recommendations made in that report have been considered by the Government in its response to the report and in the Cabinet Office’s Protecting the Debate consultation and subsequent report.8

The way in which election campaigns are conducted has also evolved since the beginning of this project, with a significant increase in the proportion of the campaign which is conducted online. This has given rise to concerns about transparency of the sources of advertising material, and the methods by which it is targeted at individual voters. The current rules requiring campaign material to state who published it only apply to printed material, and we recommend in chapter 11 of this report extending these requirements to online material.

Some of these challenges emerged after the publication of our consultation paper, and are not addressed by it. Without further consultation we are reluctant to make new recommendations here. We hope however that implementing our recommendations to modernise the framework of electoral law will mean that making changes to the law will be a less protracted and complicated process. As a result, electoral law will be able to respond faster to societal and technological developments.

The other area in which there have been developments is the balance between security from fraud and access to the poll, a policy question which in our view is a

7 Intimidation in Public Life, Report of the Committee on Standards in Public Life (December 2017) Cm 9543.

8 Cabinet Office, Protecting the Debate: Intimidation, Influence and Information (July 2018) and Cabinet Office, Response to Protecting the Debate: Intimidation, Influence and Information (May 2019).

matter for governments and parliaments. Since our interim report the Government has conducted a number of trials of voter identification at the poll, and intends to roll out the policy nationally. Following the 2015 Tower Hamlets election petition (discussed further in chapter 11) Sir (now Lord) Pickles was asked by the Government to consider what changes were necessary to make the electoral system more secure.

The resulting report on electoral fraud was published in August 2016,9 and is discussed in various places throughout this report.

The reform of electoral law was formerly a tripartite law reform project, undertaken by all three UK Law Commissions. Earlier stages of the project benefitted greatly from the work of the Northern Ireland Law Commission. That organisation became non- operational in 2015, due to budgetary pressures within the Department of Justice. The Chair of the Northern Ireland Law Commission, the Honourable Mr Justice Maguire, signed the 2016 interim report on the strength of the recent involvement of the Northern Ireland Law Commission. He has not been able to do so for this final report, and as a result its recommendations are confined to Great Britain. We continue to refer to the electoral law of Northern Ireland where this informs our recommendations.

As we have mentioned, our interim report noted the continuing process of devolution since the project began, giving rise to a need for separate legislation by the devolved legislatures. The interim report envisaged that our draft Bill (had it been produced) could serve as a template for the devolved legislatures, subject to any changes required by them. Since the interim report legislative competence in relation to certain elections has been further devolved by the Scotland Act 2016 and the Wales Act 2017. At the time of publication of this report the Welsh and Scottish Parliaments are considering bills to be enacted under these powers, which would introduce a variety of reforms to electoral law for those elections for which they have competence.10 We return to this topic in slightly more detail in chapter 2.

The conception that we had at the outset of the project, of a single Act of the United Kingdom Parliament governing all elections within the scope of the project, has therefore become outdated. We do not recommend a single Act but remain of the view that consistency of approach is valuable; one of the problems for those administering elections at present is the discrepancies that exist between the rules governing different elections, which are most problematic when such elections coincide in the same area. It is likely that UK Parliamentary elections governed by Westminster legislation will continue to coincide with elections for which legislative competence is devolved. We would encourage the legislatures to cooperate so as to avoid devolution throwing up fresh sets of discrepancies where they are avoidable.

9 Sir Eric Pickles, Securing the ballot: review into electoral fraud (August 2016).

10 We note in particular the Scottish Elections (Reform) Bill, Scottish Elections (Franchise and Representation) Bill, and the Local Government and Elections (Wales) Bill, as well as the recently passed Senedd and Elections (Wales) Act 2020 and the Referendums (Scotland) Act 2020.

We are grateful to the following members of the joint project team who worked on this report: at the Law Commission of England and Wales, Henni Ouahes (team head), Sarah Smith (team lawyer) and Liam Evans (research assistant), and, at the Scottish Law Commission, Gillian Swanson (project manager).This project, including our consultation paper and interim report, benefited extensively from meetings with individuals and organisations whose experience and expertise significantly contributed to our understanding of a complex and technical area of law, and to our thinking on how it might be simplified. We are extremely grateful to them all for giving us their time and expertise so generously. Space precludes us from naming them all,11 but we would like in particular to thank the following organisations and their staff for their time and efforts over the years: the AEA, the Electoral Commission, the Chief Electoral Officer for Northern Ireland, the Electoral Management Board for Scotland (“EMB”),

the Scottish Assessors’ Association (“SAA”), the Society of Local Authority Chief Executives (“SOLACE”) and the Society of Local Authority Lawyers and Administrators in Scotland (“SOLAR”). We also wish to thank the national agents of the main political parties and lawyers who act for and advise them, in particular David Allworthy, Piers Coleman, Alan Mabbutt OBE, Scott Martin, Gerald Shamash and Andrew Stedman, to name only some.

Finally, we would like to record our special thanks to electoral administrators who invited our staff to see for ourselves how various electoral processes, from registration and absent voting to polling and the count, take place on the ground: George Cooper (deputy returning officer at the London Borough of Haringey), Laura Locke (then deputy returning officer at Huntingdon Borough Council and now deputy Chief Executive at the AEA), and Peter Stanyon (deputy returning officer at the London Borough of Enfield and now Chief Executive at the AEA). We also wish to thank John Turner, former Chief Executive of the AEA, for his steadfast support for electoral law reform and for arranging for us to see first-hand some of the processes that are governed by the laws which are the subject of this report.

11 A full list of consultees and consultation events is contained in our interim report at Appendices B and C; see Electoral Law: A Joint Interim Report (2016) Law Com; Scot Law Com; NI Law Com. A list of members of our Advisory Group is contained in our consultation paper at Appendix B (see Electoral Law (2014) Law Commission Consultation Paper No 218; Scottish Law Commission Discussion Paper No 158; Northern Ireland Law Commission No 20).

UK electoral law is structured in an “election-specific” way. The legislation containing electoral laws is tied to, and expressed to apply to, particular elections or referendums. In reality, the legislation governing UK Parliamentary elections – which we describe as the “classical” electoral law – sets out a template on which the legislation governing all other electoral events is based. But the experience of voters at polling stations is largely uniform, no matter the election or referendum they vote at. What changes for voters, in essence, is the ballot paper and its contents. A corpus of consistent “core polling rules” therefore exists across all polls, which although identical in content is repeated in each piece of event-specific legislation.

Moreover, there is a permanent structure for running polls in the UK – a structure for registering electors, for maintaining and updating entries on the register, and for keeping and updating records of absent (postal and proxy) voters. So far, there has been no substantive departure whatsoever from the “structural” provisions governing registration and absent voting, no matter which poll is involved, across the UK. And yet, from a technical point of view, the election-specific legislation replicates these common structural provisions, often using extremely opaque and inaccessible drafting.

This approach, which our consultation paper showed was not the result of deliberate policy choices but rather an accident of history, results in a legal framework that our consultation paper described as “complex, voluminous, and fragmented”. More than 25 statutes and many more pieces of secondary legislation govern electoral events.

A large volume of legislation is arranged in a piecemeal structure, even though the content is largely identical. Only the occasional departure is made from the classical rules, not all of which are justified by a material difference such as the voting system in use. In fact, much of the complexity of the legislation – particularly that in secondary legislation – exists purely in order to ensure that there is, in effect, no departure from the classical core polling rules, or from the structural provisions governing electoral registration and absent voting.

This chapter reiterates our core and overarching approach to reform of electoral law: electoral legislation should be rationalised so that it should apply to all elections, with fundamental or constitutional matters contained in primary legislation. Detailed rules on the conduct of elections should be contained in secondary legislation so far as possible. These two proposals in our consultation paper received the most responses, and nearly unanimous support from those who responded to them.

The overarching recommendations in this chapter inform many of the recommendations made in subsequent chapters, such as absent voting in chapter 6, nominations in chapter 7, polling rules in chapter 8, and the count in chapter 9.

Our consultation paper set out the history of the legislative framework governing elections. It noted that, when the Representation of the People Act 1983 (“the 1983 Act”) was enacted, its provisions governed all elections in the UK other than European Parliamentary elections. The Representation of the People Act 1985 governed absent voting and a number of other matters. It and the 1983 Act set out the “classical” electoral law governing nearly all polls in the UK, all of which used one voting system

– first past the post.

That classical law furthermore adhered to a policy of detailed prescription. Polls must be conducted according to legal prescriptions that aim, where possible, to deal exhaustively with the conduct of the poll. The intention is that, so far as possible, returning officers are not to make subjective or qualitative assessments at key stages of polling – such as on the right to stand for election, or the right to cast a vote on polling day. Administrators are therefore, where appropriate, guided by hard and detailed rules. The advantage of this approach is that it shields returning officers and their staff from the perception of partiality in the charged atmosphere of elections. The disadvantage is that it makes for long and detailed rule books which need regular updating.

After 1999, however, many more types of election and local referendums were introduced to the statute book as a consequence of the then Labour Government’s policies of devolution in Scotland, Northern Ireland and Wales, localism in England, and the creation of the Greater London Authority. Recourse to national referendums also grew, while in due course a number of local referendums were created. Each type of election or referendum was governed by its bespoke piece of secondary legislation setting out its own election or referendum rules.

The number of sources of electoral laws therefore grew with each newly introduced poll. But two crucial factors contributed to the complexity and volume of laws. First, the new legislation continued the policy of detailed prescription in the classical law. Secondly all of the newly created elections used a voting system other than first past the post, which the classical law in the 1983 Act was designed for.12 Some of the classical law had to be adapted to account for the different voting system in use. Our consultation paper called efforts to adapt a classical rule to a new voting system “transpositions”. We noted that some of the transpositions of first past the post rules to different voting systems were not consistent, despite using the same “new” voting system.

12 Three new types of voting systems emerged, the supplementary vote, the party list, and the single transferable vote (or STV). A number of elections used a mix of the party list and first past the post, which is called the “additional member system” or AMS. This is sometimes treated as a distinct voting system, which technically it is not – it is an amalgam of two or, in the case of Greater London Authority elections, three voting systems.

Our analysis in the consultation paper, which was endorsed by most consultees, was that the reason why electoral law was “complex, voluminous and fragmented” is a combination of the following:

an election-specific approach to legislation;

a policy of detailed prescription in electoral law; and

the introduction of a number of new types of poll, all of which used a different voting system.13

We proposed that electoral laws should instead be set out in a single, consistent legislative framework which was “holistic” or pan-electoral, instead of election-specific. Our provisional view was that primary legislation should contain those aspects of electoral law which have a constitutional character or are fundamental to laying down the structure for conducting elections in the UK. The detailed administration of polling would be governed by secondary legislation. Beyond that, performance standards and guidance published by the Electoral Commission would continue to assist electoral administrators and participants in the electoral process in their conduct.14

Our first proposal was addressed by 47 consultees, nearly all of whom agreed that existing election-specific laws should be set out within a single consistent legislative framework. Many expressed strong agreement with this key proposal, and indeed many, such as the national branch of the Association of Electoral Administrators (“AEA”), have long argued for it.

Consultees variously described this proposal as “an absolutely fundamental principle and … entirely the right approach”, “long overdue” and “the single most important task of reform that is required”, referring to the “nightmare for electoral administrators and anyone else interested in elections (such as candidates) to navigate the law”. Diverse Cymru, a disability charity, described the complexity and confusion of information about elections and the processes involved in them as key barriers to participation by voters and, in particular, to standing as independent candidates.

Two points of discussion arose in consultees’ responses. The first concerned what the balance should be as between primary and secondary legislation, and the second concerned the developments in devolution across the UK and their implications for our proposed rationalised legislative framework.

One of the ways in which election laws diverge is their location in the hierarchy of laws: primary and secondary legislation. For UK Parliamentary elections, all of the “classical” laws, even those to do with the detail of administering a poll, are in primary

13 Electoral Law (2014) Law Commission Consultation Paper No 218; Scottish Law Commission Discussion Paper No 158; Northern Ireland Law Commission No 20, paras 2.4 to 2.15.

14 As above, paras 2.24 to 2.35.

legislation. For other elections, very little is in primary legislation and secondary legislation contains nearly all the laws governing them.

Primary legislation (an Act) is passed by a Parliament and can generally only be changed by a new Act; it cannot be over-ridden by the Government of the day without the consent of Parliament.15 On the other hand, the process of amending primary legislation by a new Act is cumbersome where the amendment relates to a purely technical or administrative aspect of electoral law. Secondary legislation (usually in the form of regulations) is made, typically by Ministers, under powers conferred by Parliament in primary legislation. Regulations are relatively straightforward to make and to amend.

Primary legislation is therefore the right place for important rules of law which Ministers should not be able to depart from without the fullest Parliamentary scrutiny. This view reflects that of the House of Lords Delegated Powers and Regulatory Reform Committee, namely that “substantial changes to electoral law” should be reserved to primary legislation.16 Rules on matters of detail, which may need to be adapted to changes in circumstances, are better placed in secondary legislation.

A detailed articulation of which provisions should be in primary legislation and which should be in secondary legislation is best undertaken when the work of drafting an electoral Bill is under way. However, in our consultation paper, we identified, at an abstract level, certain topics which we considered to be “important” or fundamental aspects of electoral law which should be in primary legislation. We remain of the view that these are:

the electoral franchises;

the voting system;

the apparatus for electoral administration, including:

the electoral register and registration officer infrastructure;

absent voting mechanisms and records; and

returning officers, their powers and their responsibility for conducting elections.

fundamental provisions on elections such as:

the relationship between nominations, polling and the count;

the election timetable;

15 Unless the Act confers a power to the Government to amend the Act in particular ways by secondary legislation.

16 Committee on Delegated Powers and Deregulation’s 37th Report for the 1999-2000 Parliamentary session, (1999-2000) HL 130, para 36.

important principles governing the conduct of the poll, such as voting by ballot, secrecy and security, and the powers to prescribe detailed conduct rules for elections, ballot papers and other forms;

the regulation of the election campaign and electoral offences; and

provisions on legal challenge to elections. 17

These headline-level provisions are concerned with electoral laws which have constitutional importance or which are fundamental to the system for organising and running polls in the UK. They include matters such as the franchise, the use of a voting system, and legal challenge to elections. They also include the principles that voting should be by ballot and in secret; article 3 of the First Protocol to the European Convention on Human Rights requires contracting parties to hold free elections at reasonable intervals “by secret ballot”. We would also add electoral law offences to the list, given their central role in regulating the electoral campaign and policing the conduct of both the public and campaigners at elections and referendums.

We also consider that a provision can be described as fundamental if it relates to an important and long-standing feature of electoral law. For example, the notion that a person’s entry on the register absolutely governs their right to vote at a polling station, and that this is established in advance, is fundamental to electoral law – it is not the only conceivable answer to the issue of how to establish entitlement to vote, but it has been the UK’s answer for a century and a half. For these reasons, we consider that all of those matters ought to be dealt with in primary legislation.

Consultees broadly agreed with our list of provisions which should be included in primary legislation.

The national branch of the AEA suggested that a distinction is drawn between high- level matters and principles which reflect electoral policy, and the detailed rules relating to electoral registration and the conduct of elections, which are suitable for inclusion in secondary legislation.

Similarly, the Electoral Commission considered the rationale for our proposed legislative hierarchy to be sound. It expressed a hope that one of the results of implementing our recommendation would be that detailed rules were moved lower down the hierarchy, to secondary legislation or Electoral Commission guidance, so as to allow greater flexibility.

One consultee, Sir Howard Bernstein (then returning officer of Manchester City Council) saw “the special status that the legislature appears to have deliberately afforded to the legislation governing UK parliamentary elections” as a potential difficulty for our proposed breakdown between primary and secondary legislation. He doubted that this special status was an “accident of history” and argued instead that it reflected a political policy decision that even the detailed administrative rules governing elections to the UK Parliament should be subject, on account of their

17 Electoral Law (2014) Law Commission Consultation Paper No 218; Scottish Law Commission Discussion Paper No 158; Northern Ireland Law Commission No 20, paras 2.30 to 2.34.

particular constitutional importance, to the full parliamentary scrutiny that primary legislation entails.

In our interim report we took this point very seriously, but explained that the way in which our consultation paper had proposed to deal with it was by ensuring that primary legislation should continue to contain those aspects of electoral law that have a constitutional or fundamental character.

It remains reasonably clear to us that the allocation of some rules to primary or secondary legislation is an accident of history. Those rules which have their origins in the Ballot Act 1872 continue to be in primary legislation, even though some concern matters of an incidental character, such as the duty of a returning officer to publish a copy of any petition challenging the result of the election in the area. Those rules that have a different or later origin tend to be located in secondary legislation, even if they are fundamental or important.

By way of example, until the Representation of the People Act 2000 (“the 2000 Act”) was passed, there was no high-level statement describing how an elector might cast their vote in the UK. To establish the position prior to that, it was necessary to read together a number of provisions, including provisions in the 1983 Act on identification of polling districts, the Parliamentary elections rules (which set out that the poll is to be taken by ballot)18 and the provisions on issue and receipt of postal votes contained in secondary legislation. By contrast, Schedule 4 to the 2000 Act, does set out how an elector may vote; either at the polling station, or by post or by proxy (even though the schedule is entitled “Absent Voting”).19 But this legislative provision only applies to parliamentary and local government elections; its application to other elections is dependent on election-specific statutory instruments either instructing the reader to treat those elections as local government elections, or repeating the 2000 Act provision in the relevant instrument. A curious result is that the fundamental provision that voting is by ballot, at an allotted polling station, or by post or proxy by prior application, is contained in primary legislation for some elections (such as local government elections) and in secondary legislation for others (such as Police and Crime Commissioner elections).20

It is not our intention to shift important matters from primary to secondary legislation, but rather to modernise and simplify primary legislation so that it addresses, for all elections, the fundamental elements of a lawful poll and provides power to deal with matters of detailed electoral administration by way of secondary legislation, which are also subject to Parliamentary scrutiny.21

The evolving devolutionary picture was raised by several consultees. It was also raised at our meetings with national agents of political parties. We suggested in our consultation paper that reformed electoral law should be set out in the fewest possible

18 Representation of the People Act 1983, sch 1, r 18.

19 Representation of the People Act 2000, sch 4, para 2.

20 Police and Crime Commissioner Elections Order 2012 SI No 1917, art 11 and sch 2.

21 Electoral Law: A Joint Interim Report (2016) Law Com; Scot Law Com; NI Law Com, paras 2.10 to 2.16.

pieces of legislation consistent with the devolutionary structure. It was clear to us that the devolutionary picture was likely to change during the life of this project. We acknowledged in the consultation paper and our interim report that a single Act of the UK Parliament might not be feasible and that separate primary legislation for the different jurisdictions in the UK might be necessary.22 We do so again now.

We summarise below the legislative competence of the Scottish and Welsh Parliaments this area. For completeness we note that the Northern Ireland Assembly has no legislative competence in respect of elections.23

At the time we published our consultation paper the Scottish Parliament had legislative competence over local government elections in Scotland (except for the franchise). Some powers to make or modify secondary legislation had been transferred from the Secretary of State to the Scottish Ministers. The Scotland Act 2016, which was a Bill in Parliament at the time our interim report was published, now implements the Smith Commission’s proposal for full legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament over its own elections as well as local government elections in Scotland.24 The Scottish Parliament has nearly full legislative competence over both local government elections in Scotland and Scottish Parliamentary elections, with only certain aspects of the incidence and combination of polls reserved to the UK Parliament.25

Also reserved to the UK Parliament is the digital service for online applications to register that may be introduced by UK Ministers, and certain parts of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000, notably the registration of political parties and control of donations to registered parties.26

So far as matters within the scope of this reform project are concerned, however, overwhelmingly the law concerning elections to the Scottish Parliament will be a matter for that Parliament. The Scotland Act 2016 introduced a new section 12 into

22 Electoral Law (2014) Law Commission Consultation Paper No 218; Scottish Law Commission Discussion Paper No 158; Northern Ireland Law Commission No 20, para 2.31. Electoral Law: A Joint Interim Report (2016) Law Com; Scot Law Com; NI Law Com, para 2.19. See further para 2.40 below regarding legislative consent motions.

23 Elections to the UK Parliament, Northern Ireland Assembly, and local government (district council) elections are excepted from the competence of the Assembly. See Northern Ireland Act 1998, ss 34(4) and 84, and sch 2, paras 2 and 12.

24 The Smith Commission, Report of the Smith Commission for further devolution of powers to the Scottish Parliament (November 2014), available at https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20151202171017/http://www.smith-commission.scot/ (last visited 3 March 2020); Scotland in the United Kingdom: An enduring settlement (January 2015) Cm 8990, available at https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/397079/Scotland_EnduringSe ttlement_acc.pdf (last visited 3 March 2020).

25 Scotland Act 2016, ss 3 to 9, particularly ss 3(4), 4(1), 4(2) and 5. Combination of polls is discussed in chapter 10.

26 Scotland Act 2016, s 3(4).

the Scotland Act 1998 which provides Scottish Ministers with the power to make provision about elections, including:

the conduct of elections for membership of the Parliament;27

the challenge of such an election and the consequences of irregularities; and

the return of members of the Parliament otherwise than at an election.28

In addition, the Scottish Parliament has power to modify certain sections of the Scotland Act 1998, which include section 12 itself. Therefore, where we recommend that rules that are currently in secondary legislation should be in primary legislation, it is the Scottish Parliament that has the power to implement our recommendations, and it is to the Scottish Government that our recommendations are addressed.

The devolution settlement over electoral law in Wales is contained in Part 1 and Part 2 of Schedule 7A of the Government of Wales Act 2006 (“the 2006 Act”). It used to be based on a “conferred powers” model, meaning that the National Assembly for Wales could only legislate within the specific competences conferred to it in the 2006 Act, but the Wales Act 2017 has followed the “reserved powers” approach in use for Scotland. The effect is that the Assembly29 has legislative competence over its own elections, local government elections in Wales, and (mayoral) referendums under Part 2 of the Local Government Act 2000, subject to similar limitations to those in Scotland – the incidence, and combination of certain polls, the online registration facility and the subject matter of parts of the Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000.30

The Electoral Commission’s support for our proposed legislative framework, with consistent rules governing all elections, was subject to achieving these aims within the evolving devolutionary picture. The Electoral Commission doubted the feasibility of

UK-wide legislation governing elections competence over which was devolved.

The Scottish Government saw it as important to “balance the desire for a consistent framework with the fact that some elections, or aspects of elections, are (or will be) devolved to the Scottish Parliament”, enabling Scottish Ministers “to propose electoral reforms that best reflect the needs of the Scottish electorate.”

Scott Martin (Scottish National Party) saw the devolved legislative competence of the Scottish Parliament and Scottish Ministers as “fundamental to the whole project”. He drew our attention to a number of exercises by the Scottish Parliament of legislative competence regarding elections and the development of a number of distinct policies as to electoral administration. He also noted the abstention of the UK Parliament from legislating in respect of Scottish local government elections since those became a

27 This includes registering electors and limiting candidates’ expenditure.

28 Scotland Act 2016, s 4(1).

29 Soon to be renamed the Welsh Parliament or Senedd Cymru: see para 1.11 above.

30 Government of Wales Act 2006, sch 7A, Part 2 (Specific Reservations) Reservation, Head B1.

devolved matter and observed that the recent divergence in the application of the 1983 Act in Scotland and in England and Wales had been a source of confusion.

The Scottish and Welsh Parliaments have almost full legislative competence over the conduct of and challenge to their respective devolved elections. By virtue of the Sewel convention,31 the UK Parliament will not normally legislate for devolved matters without the concurrence of the devolved legislatures. As we noted in our interim report, our reformed legislative framework must necessarily reflect this constitutional arrangement. It is not for us to speculate about (or make recommendations as to) the passing of legislative consent motions in the devolved legislatures so that electoral laws are contained in a single, UK piece of legislation. The legislatures in Holyrood and Cardiff Bay have recently passed legislation governing their own elections and referendums, and other Bills are under consideration.32

We are therefore proceeding on the assumption that, if the UK, Scottish and Welsh Governments accept our recommendations, each Government would introduce primary legislation governing electoral events within the legislative competences of the respective parliaments. The Secretary of State, the Scottish Ministers and the Welsh Ministers would respectively make provision by way of secondary legislation for the elections covered by each piece of primary legislation.

The result would be that an Act of the UK Parliament, and secondary legislation made under it, would govern UK-wide elections, elections in England, and any aspects of elections in Scotland or Wales for which legislative competence is not devolved.33 Separate Acts of the Scottish and Welsh Parliaments would govern elections within Scotland and Wales respectively as regards matters within the two legislatures’ competences.

Our consultation paper noted that the fragmented and piecemeal legislative framework poses problems not only for those referring to the law, such as electoral administrators, campaigners, and voters, but also for policy makers. Legislation introducing a new election must address every aspect of the existing electoral law; failing to do so introduces risk to the legality of electoral outcomes. For example, urgent secondary legislation had to be introduced in 2012 to enable Welsh language ballot papers to be used at Police and Crime Commissioner elections in Wales. The

31 The Scotland Act 2016, s 2, amended s 28 of the Scotland Act 1998 to put the Sewel convention into statutory form in relation to matters devolved to the Scottish Parliament. The Wales Act 2017 similarly amended the Government of Wales Act 2006 to include the Sewel Convention at s 107(6).

32 The Scottish Parliament has passed the Referendums (Scotland) Act 2020, and is currently considering the Scottish Elections (Reform) Bill and the Scottish Elections (Franchise and Representation) Bill. In Wales, the Senedd recently passed the Senedd and Elections (Wales) Act, and the Local Government and Elections (Wales) Bill was introduced on 18 November 2019.

33 While this report does not make recommendations in relation to the law of Northern Ireland, we note here that it would be consistent with the current devolutionary position for that Act also to govern elections in Northern Ireland, along with secondary legislation made by the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland.

power to do so had long before been introduced, but only for elections governed by particular legislation.

Similarly, introducing a new policy, such as allowing those queuing at the close of polls to cast their vote, requires several separate pieces of legislation for each type of election, even though that policy was approved by the fullest process of legislative scrutiny available – amending primary legislation in 2013. Instead of applying across the board, each piece of election-specific legislation then had to be amended – and opened to scrutiny by MPs who had already voted on the amendment in 2013. Meanwhile, those who wish to ascertain the law governing elections need to consult separate pieces of legislation, sometimes containing puzzling discrepancies. Finally, the volume of the legislation is unnecessarily swollen by needless repetition.34

All of this is, in the final analysis, unnecessary complexity. The reader should be able to consult one main source of the law governing elections (subject, of course, to devolution in Scotland and Wales, where the reader may need to consult a different statute). Policies need only be developed once, drafted once, and scrutinised once. Core polling rules and the structural provisions on registration and absent voting should be expressed as applying to all existing elections, and apply to any new elections introduced by the legislature later.

We are therefore minded to maintain the recommendation in our interim report, given the level of support for our key overarching aim of setting out electoral laws in a holistic or pan-electoral law. That aim is subject to the devolutionary framework, meaning that references to a single Act should be read as referring to, in all likelihood, an Act of the UK Parliament, a Scotland-only Act (governing devolved elections in Scotland), and a Wales-only Act (governing devolved elections in Wales).

A necessary concomitant of our first proposal to rationalise electoral law was to make its content as consistent across all elections as possible. We identified two principles which could legitimately cause election law to differ from one election to another.

The first was the need to adapt the law to the use of a particular voting system. Much of our concern in the consultation paper was to derive consistent “transpositions” of classical election laws for each voting system in use in the UK.

34 Electoral Law: A Joint Interim Report (2016) Law Com; Scot Law Com; NI Law Com, para 2.2.

The second principle was that a deliberate policy reason should exist to justify the difference. While particular divergences in policy may be justified for particular elections, many of the divergences in election laws identified in our consultation paper in fact appeared to us to be caused by inconsistent approaches to adaptation to the use of a new voting system, or accidents of drafting.

Nearly all of the 46 consultees who responded to this provisional proposal agreed with it.

A number of key stakeholders, including the Electoral Commission, the Society of Local Authority Chief Executives and Senior Managers (“SOLACE”) endorsed our aim of reducing the amount of election-by-election divergence to those which are necessary and justified by the voting system or a policy choice. Scott Martin (Scottish National Party) noted that divergences of policy existed in Scotland because of deliberate political choices by the Scottish Government and Parliament.

We remain of the view that it is important to analyse electoral laws and the differences in each rule book and seek to derive, as far as possible, a general and consistent set of rules for elections, and to articulate in a consistent way the adaptations to the common rules that are appropriate or required by the use of any particular voting system. Of course, there will be considered departures from standard policies for particular elections. This will especially be the case as priorities and policy preferences diverge in each of the three legislatures in the UK with competence to make electoral law.

We note, however, that some form of devolved competence over particular elections has been in place since 1999, and a significant amount of electoral law in Scotland and Wales has been devolved since 2016; nonetheless, the experience of voters, and the structural rules on registration and absent voting, have remained highly uniform. This may in part be because electoral administrators in Scotland and Wales are inevitably tasked with running UK wide elections (such as UK parliamentary elections) in accordance with the 1983 Act (and, as relates to absent voting, the Representation of the People Act 2000), potentially in combination with elections for which legislative competence is devolved. Divergence between the legislation governing these various elections may make the task of electoral administrators in Scotland and Wales unduly complicated.35

35 In practice, unintended divergence can be managed through cooperation between governments and stakeholders as policy develops and legislation is drafted; we note by way of example the working partnership between Governments, the Electoral Commission, the Association of Electoral Administrators and the Scottish Assessors’ Association in developing proposals for reform of the annual canvas.

We think it is time that the 1983 Act is replaced by a holistic, simpler piece of primary legislation, under which secondary legislation governing the detail of particular polls is made. The Scottish and Welsh legislatures can decide, as they do now, which parts of the UK statute they replicate or adopt. What would emerge under this framework is much more satisfactory than the out-of-date and labyrinthine framework under which everyone, from voter to administrator, and from campaigner to civil servant, is bound to struggle with. We are therefore minded to maintain our recommendation in the interim report.

2.56 Electoral laws should be consistent across elections, subject to differentiation due to the voting system or some other justifiable principle or policy.

We have published on our website specimen drafting illustrating how elections rules governing three polls in England (and their combination with other polls) might be brought together.36 These are polls whose current conduct rules are subject to the same affirmative procedure of scrutiny in Parliament. The draft is not finalised and cannot be introduced without further work by Government, but we are publishing specimen drafting in order for stakeholders to see what a single set of conduct rules governing multiple polls might look like. The recommendations in this chapter are aimed largely at primary legislation under which secondary legislation would deal with the detail. We did not suggest in the interim report that detailed conduct rules should also be set out in a pan-electoral or holistic manner – it is perfectly intelligible to continue to have bespoke detailed election-specific rules. But there is an advantage in setting out, in a single place, the shared or common parts of the rulebook. Our specimen drafting seeks to do that; in doing so, it reduces one species of complexity that arises out of the volume of legislation and its fragmented sources. But it does introduce some extra detail – and thus another form of complexity – in order to deal adequately with different types of poll.

One of the reasons why we have published the specimen drafting is to illustrate one of the challenges of expressing electoral law holistically. As we note above, electoral law seeks to be detailed in its prescription. As a result, the level of prescription does occasionally mean that our specimen drafting is lengthy and detailed. The existing powers to make secondary legislation limit the extent to which delegated legislation can set out rules that are radically simpler. This is because the Secretary of State is required to apply the classical rules (Parliamentary elections rules in schedule 1 to the 1983 Act) subject to adaptations, alterations and exceptions.37 Our specimen drafting nonetheless sought sensibly to opt for less detailed prescription where one rulebook omitted a piece of detail which was included in another. In that case, the duty to refer to the Electoral Commission’s guidance (which is a perfectly proper place for election-

36 Available at https://www.lawcom.gov.uk/project/electoral-law/.

37 Representation of the People Act 1983, s 36(2).

specific detail based on experience and best practice), and powers of direction were adequate to deal with particular scenarios, such as requiring a local returning officer to publish the notice of election in their electoral area.

Our experience of drafting within the existing, restrictive powers in the 1983 Act suggests that there is a limit to how simple they can be made to be. Transferring some of the detailed administrative provisions to guidance, or relying on administrative good sense backed by powers of direction, can help to simplify elections rules further. This is particularly the case if these rules are to be expressed in a standard and holistic way to more than one type of election. Departing from the classical approach of exhaustive, detailed prescription is plainly an important policy decision which will need to be considered by Governments in due course on a consensus-building basis with electoral administrators, the Electoral Commission, parties and groups representing voters.

Electoral administration involves, first, the permanent task of maintaining the register of electors and absent voting records and, secondly, running elections when they are called. The law allocates these tasks to a registration officer and a returning officer respectively. This chapter considers the legislative framework governing the oversight and management of elections by returning officers. Electoral registration is considered in the next chapter.