The Law Commission

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> The Law Commission >> Automated vehicles [2022] EWLC 404 (January 2022)

URL: https://www.bailii.org/ew/other/EWLC/2022/LC404.html

Cite as: [2022] EWLC 404

|

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback] [DONATE] | |

The Law Commission |

||

|

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> The Law Commission >> Automated vehicles [2022] EWLC 404 (January 2022) URL: https://www.bailii.org/ew/other/EWLC/2022/LC404.html Cite as: [2022] EWLC 404 |

||

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Scottish Law Commission

Automated Vehicles: joint report

HC 1068

SG/2022/15

Law Com No 404

Scot Law Com No 258

Law

Scottish Law Commission

Commission

Reforming the law

Law Commission of England and Wales

Law Commission No 404

Scottish Law Commission

Scottish Law Commission No 258

Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 3(2) of the Law Commissions Act 1965

Laid before the Scottish Parliament by the Scottish Ministers

Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed on 25 January 2022

HC 1068

© Crown copyright 2022

This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3.

Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned.

This publication is available at www.gov.uk/official-documents.

Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at [email protected] or [email protected]

Print ISBN 978-1-5286-3149-5

E02712832 01/22

Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum

Printed in the UK by the HH Associates Ltd. on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty's Stationery Office

The Law Commissions

The Law Commission of England and Wales and the Scottish Law Commission were set up by the Law Commissions Act 1965 for the purpose of promoting the reform of the law.

The Law Commissioners of England and Wales are:

The Right Honourable Lord Justice Green, Chair

Professor Sarah Green

Professor Nick Hopkins

Professor Penney Lewis

Nicholas Paines QC

The Chief Executive of the Law Commission of England and Wales is Phil Golding.

The Law Commission is located at 1st Floor, Tower, 52 Queen Anne's Gate, London

SW1H 9AG.

The Scottish Law Commissioners are:

The Right Honourable Lady Paton, Chair

David Bartos

Professor Gillian Black

Kate Dowdalls QC

Professor Frankie McCarthy

The Interim Chief Executive of the Scottish Law Commission is Charles Garland.

The Scottish Law Commission is located at 140 Causewayside, Edinburgh, EH9 1PR.

The terms of this report were agreed on 8 December 2021

The text of this report is available on the Law Commission's website at

https://www.lawcom.gov.uk/project/automated-vehicles/

https://www.scotlawcom.gov.uk/law-reform/law-reform-projects/joint-projects/automated-vehicles/

iv

Contents

The rationale for regulating automated vehicles

What is an “automated vehicle” (AV)?

A focus on passenger transport

Areas outside the scope of this report

When should a vehicle be considered as able to drive itself safely?

Safety assurance: initial authorisation and in-use safety

Regulating marketing about driving automation

New legal actors: the user-in-charge and NUIC operator

Additional material published alongside this report

The team working on this review

The operational design domain (ODD)

Automated vehicles, systems and features

Automated Lane Keeping Systems (ALKS)

Explaining driving automation to the public

Authorised Self-Driving Entity (ASDE)

The Secretary of State’s safety standard

Approval and authorisation as self-driving

The definition in the Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018

“Monitoring” in the SAE Taxonomy

Our approach to monitoring in Consultation Paper 3

Conclusion: an individual does not need to monitor

Receptivity of a user-in-charge to a transition demand

Requirements for transition demands

Sufficient time to gain situational awareness

The consequences of failing to take over control

Responding to events in the absence of a transition demand

The SAE view: responding to system failures, such as a tyre blow-out

The German view: “obvious circumstances”

France and Australia: responding to emergency vehicles

Our proposal in Consultation Paper 3

Conclusion: no requirement to respond without a transition demand 46

The monitoring test for vehicles without a user-in-charge

Recommendation: writing the threshold for self-driving into law

Permitted activities for the user-in-charge

Preventing dangerous interventions by the user-in-charge

Possible safety standards: consultees’ views

Option C: Safer than the average human driver

Option A: As safe as a competent and careful driver

Option B: As safe as a human driver who does not cause a fault accident

Equity in the distribution of risk

Safety standards: summarising the debate

Who should set a safety standard?

How would a safety standard be used?

The role of the safety standard pre-deployment

The role of the safety standard when vehicles are in-use

Overview of our proposed approval and authorisation system

Domestic AV technical approval

Why is the authorisation stage necessary?

Support for a second authorisation stage

Authorisation outcomes: the effect of failing to gain authorisation

Different outcomes for different features?

Duties on the ASDE arising from authorisation

Should AV authorisation and the in-use scheme have the same regulator?

In-use safety scheme: responsibilities

Investigating traffic infractions involving AVs

New powers to apply regulatory sanctions

Existing powers under the General Product Safety Regulations 2005

Suspending and withdrawing authorisation

Should the regulator have a consumer protection role?

A forum to collaborate on road rules

Driving automation that is not self-driving

Experience in other jurisdictions

Offence 1: Describing unauthorised driving automation as “selfdriving”

Offence 2: Misleading drivers that a vehicle does not need to be monitored

Online marketing across jurisdictions

CHAPTER 8: THE ROLE OF A USER-IN-CHARGE

The definition of a user-in-charge

In position to operate the vehicle controls

Consultation Paper 3 proposals

Support for requirements to be qualified and fit to drive

Causing or permitting an unfit or unqualified person to be a user-in-charge

Being carried without a user-in-charge

What if an AV requiring a user-in-charge is made to drive empty?

Provisionally licensed drivers

The immunity from dynamic driving offences

The user-in charge’s immunity: recommendation

“Engaged” or “correctly engaged”?

The liability of a user-in-charge for non-dynamic driving offences

Ensuring child passengers wear seatbelts

Communicating the dynamic/non-dynamic distinction to users

Committing dangerous driving offences through non-dynamic failures 155

The effect of section 40A of the Road Traffic Act.

A new offence for users-in-charge

Drafting the dynamic/non-dynamic distinction

Criminal liability following handover

A specific defence where problems are brought about by the ADS

Failing to respond to a transition demand

Reacquiring driver obligations

Professional users-in-charge and passenger services

CHAPTER 9: NUIC OPERATOR LICENSING

Policy development: From HARPS operators to NUIC operators

The need for a NUIC operator to oversee the journey

What oversight duties will arise?

Remote assistance compared to remote driving

Is the remote assistant role safety-critical?

The challenges of running a remote operations centre

Regulating the organisation or the individual?

Safety-critical updates and cybersecurity

Model 1: Combining the ASDE and operator roles

Model 2: A separate NUIC operator

Model 3: Privately-owned NUIC vehicles

Model 4: NUIC operation confined to a geographically limited location 177

Recommendation: All NUIC vehicles to have a licensed operator

Recommendation: Requirements for being a NUIC operator

An establishment in Great Britain

Demonstrating professional competence

Recommendation: submitting a safety case

A potential NUIC operator must submit a safety case

Recommendation: setting licence conditions

Recommendation: powers of the regulator

How long should a NUIC operator licence last?

The role of criminal offences and traffic management penalties

Who should administer NUIC operator licensing?

Issues not addressed in this report

Tier 2 duties for freight services

CHAPTER 10: NUIC PASSENGER SERVICES

The challenges of running passenger services without a driver

Passenger services in other jurisdictions

An interim permit procedure for NUIC passenger services

A new procedure to grant interim passenger permits

Would vehicles need to be authorised?

An obligation to publish information on safeguarding and accessibility 200

Taxi and private-hire type services: the need for consent

NUIC passenger services and bus service regulation

Consultation with road authorities and the emergency services

Enforcing the requirement for an interim passenger permit

National accessibility standards and a statutory advisory panel

Longer term options for passenger services

What we said in Consultation Paper 3

When would the offences apply?

Information to both the authorisation authority and the in-use regulator 212

Extending the offence to NUIC operators as well as ASDEs

A continuing duty to provide information?

Defining “safety-relevant information”

Misrepresentations and non-disclosures to overseas regulator

The criminal liability of senior managers

Alternative definitions of senior management

The nominated person who signs the safety case

Criminal liability of senior managers: the overall effect

A new offence for other employees?

Aggravated offence for death or serious injury

Aggravated offences in road traffic law

Summary of recommended changes to wrongful interference offences

Should section 22A extend to Scotland?

New aggravated offence of causing death by wrongful interference

Responses to Consultation Paper 3

Mental state: intent to interfere

Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018: a brief overview

Contributory negligence and causation

Consultation Paper 3 proposals

Responses to Consultation Paper 3

Secondary claims under the Consumer Protection Act 1987

Problems with how product liability law treats software

Not essential for the introduction of AVs

Responses to Consultation Paper 3

ABI: Association of British Insurers.

ADS: Automated Driving System.

ADSE: Automated Driving System Entity.

AEV Act: Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018.

ALKS: Automated Lane Keeping System.

ASDE: Authorised Self-Driving Entity.

AV: Automated Vehicle.

AVP: Automated Valet Parking.

BPRs: Business Protection from Misleading Marketing Regulations 2008, SI No 1276.

BSI: British Standards Institution.

CAV: Connected and Autonomous Vehicle.

CCAV: Centre for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles.

CP1: Consultation Paper 1.

CP2: Consultation Paper 2.

CP3: Consultation Paper 3.

CPRs: Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008, SI No 1277.

DDT: Dynamic Driving Task.

DfT: Department for Transport.

DPTAC: Disabled Persons Transport Advisory Committee.

DSSAD: Data Storage Systems for Automated Driving.

DVSA: Driver and Vehicle Standards Agency.

EDR: Event Data Recorder.

GB: Great Britain.

GDPR: United Kingdom General Data Protection Regulation (EU) 2016/679.

GPSR: General Product Safety Regulations 2005, SI No 1803.

HARPS: Highly Automated Road Passenger Service.

HGV: Heavy Goods Vehicle.

HSW Act 1974: Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974.

IEEE: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers.

IVA: Individual vehicle approval.

ISO: International Organization for Standardisation.

MIB: Motor Insurers’ Bureau.

MIT: Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

MSU: Market Surveillance Unit.

NUIC: No User-in-Charge

NUIC operator: No User-in-Charge vehicle operator.

ODD: Operational Design Domain.

OECD: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

OEM: Original Equipment Manufacturer.

PSV: Public Service Vehicle.

RoSPA: Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents.

SAE: Society of Automotive Engineers International.

SMMT: Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders.

StVG: Strassenverkehrsgesetz (the German Road Traffic Act).

TfL: Transport for London.

TfWM: Transport for West Midlands.

UIC: User-in-charge.

UNECE: United Nations Economic Commission for Europe.

VCA: Vehicle Certification Agency.

ABI/Thatcham Report: Association of British Insurers (ABI) and Thatcham Research, Defining Safe Automated Driving. Insurer Requirements for Highway Automation (September 2019).

ALKS Regulation: UN Regulation 157 on uniform provisions concerning the approval of vehicles with regard to Automated Lane Keeping Systems E/ECE/TRANS/505/Rev.3/Add.156 (ALKS Regulation). It was made under the procedures set out in the UNECE 1958 Agreement (below) and entered into force on 22 January 2021.

Approval authority: Under the UNECE 1958 Agreement (described below), each Contracting Party must specify an approval authority. The approval authority has responsibility for issuing approvals pursuant to a UN Regulation, though it may designate technical services to carry out testing and inspections on its behalf. The approval authority for the UK is the Vehicle Certification Agency (VCA).

Authorisation authority: A new role recommended in this report. It will be the government agency responsible for the second stage (authorisation) of AV safety assurance in Great Britain. When authorising the vehicle, the authorisation authority will assess each of the vehicle’s ADS features and specify those which are “self-driving”. The authorisation authority will also assess whether the entity putting the vehicle forward for authorisation has the reputation and financial standing required to be an ASDE. See Chapter 5.

Automated Driving System (ADS): A term used in the SAE Taxonomy to describe a vehicle system that uses both hardware and software to perform the entire dynamic driving task on a sustained basis.

Automated Driving System Entity (ADSE): We used this term in Consultation Papers 1 and 3 to refer to the entity we now call an Authorised Self-Driving Entity (ASDE) (see below).

Automated Driving System (ADS) feature: A part of an ADS designed to operate in a particular operational design domain. As single automated vehicle may have several features: see Chapter 2.

Automated Lane Keeping System (ALKS): An ADS feature which steers and controls vehicle speed in lane for extended periods on motorway-type roads. See Chapter 2.

Authorised Self-Driving Entity (ASDE): A role recommended in this report. It is the entity that puts an AV forward for authorisation as having self-driving features. It may be the vehicle manufacturer, or a software designer, or a joint venture between the two. We discuss the ASDE role and its associated obligations in Chapter 5. We previously referred to it as an Automated Driving System Entity (ADSE).

Automated vehicles: A general term used to describe vehicles which can drive themselves without being controlled or monitored by an individual for at least part of a journey. They have an ADS able to perform the entire dynamic driving task.

Commercial practice: Defined in the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations 2008 as “any act, omission, course of conduct, representation or commercial communication (including advertising and marketing) by a trader, which is directly connected with the promotion, sale or supply of a product to or from consumers, whether occurring before, during or after a commercial transaction (if any) in relation to a product”.

Conditional automation: A term used in the SAE Taxonomy to describe an automated driving system which can perform the entire dynamic driving task but with the expectation that a user will be receptive and respond appropriately to requests to intervene and to certain failures affecting the vehicle: SAE Level 3.

Consultation Paper 1: The first consultation paper in the joint review of automated vehicles by the Law Commission and Scottish Law Commission. It was published in November 2018 and is available at: https://www.lawcom.gov.uk/project/automated-vehicles/.

Consultation Paper 2: The second consultation paper in the joint review of automated vehicles by the Law Commission and Scottish Law Commission. It was published in October 2019 and is available at: https://www.lawcom.gov.uk/project/automated-vehicles/.

Consultation Paper 3: The third consultation paper in the joint review of automated vehicles by the Law Commission and Scottish Law Commission. It was published in December 2020 and is available at: https://www.lawcom.gov.uk/project/automated-vehicles/.

Cybersecurity Regulation: UN Regulation 155 on uniform provisions concerning the approval of vehicles with regards to cybersecurity and cyber security management system E/ECE/TRANS/505/Rev.3/Add.154. It was made under the procedures set out in the UNECE 1958 Agreement (below) and entered into force on 22 January 2021.

Driver support: Driving automation features such as adaptive cruise control or lane changing features which support the driver. The driver is still responsible for the dynamic driving task, including monitoring the environment.

Driving automation: A generic term used in the SAE Taxonomy to apply to all six levels of automation. It covers the full range of driving technology, from driver support features to automated driving features capable of carrying out the whole dynamic driving task.

Dynamic Driving Task (DDT): A term used in the SAE Taxonomy to describe the real-time operational and tactical functions required to operate a vehicle in on-road traffic. It includes steering, accelerating and braking together with object and event detection and response. See Chapter 2.

Fault accident: An accident where, if a human driver had driven the car instead of an ADS, the driver would be held liable for causing the accident in the civil law of negligence.

GB whole vehicle approval: We use this term to refer to the three domestic schemes to approve vehicles in Great Britain: individual vehicle approvals (IVAs), GB small series approvals and GB Type Approval. See Chapter 5.

Haptic: Involving the transmission of information through the sense of touch. Haptic alerts may (for example) shake the seat or vibrate the seat belt.

HARPS: Highly automated road passenger services. We used this term in Consultation Paper 2 to refer to a service which uses highly automated vehicles to supply road journeys to passengers without a human driver or user-in-charge. In this report we discuss the regulation of such passenger services through interim passenger permits, as set out in chapter 10.

HF-IRADS: Human Factors in International Regulations for Automated Driving Systems group position paper submitted on 18 September 2020 to the Global Forum for Road Traffic Safety.

Highly automated vehicle: A term used in the SAE Taxonomy to describe a vehicle equipped with an automated driving system which can perform the dynamic driving task without requiring a user to be receptive to requests to intervene. Also known as SAE Level 4.

Human factors research: The study of how humans behave, both physically and mentally, in relation to particular environments, systems, products or services. Also sometimes referred to as ergonomics.

Individual vehicle approval (IVA): The approval scheme for vehicles and trailers which have been imported, assembled or manufactured as individual vehicles. The scheme checks that vehicles meet required technical, safety and environmental standards. The Driver and Vehicle Standards Agency (DVSA) administers the scheme in Great Britain.

Interim passenger permit: A new provision recommended in this report. The permit would be granted by ministers for passenger services using NUIC vehicles. See chapter 10.

In-use regulator: A new role recommended in this report. The in-use regulator will have statutory duties and powers to maintain in-use safety once AVs are deployed on GB roads. See Chapter 6.

Minimal risk condition: A term used in the SAE Taxonomy to describe a stable, stopped condition to which a user or an ADS may bring a vehicle to reduce the risk of a crash when a given trip cannot or should not be continued.

No user-in-charge (NUIC) vehicle: A new category recommended in this report. It refers to a vehicle equipped with one or more ADS features designed to perform the entire dynamic driving task without a user-in-charge.

Operational design domain (ODD): A term used in the SAE Taxonomy to describe the domain within which an automated driving system can drive itself. It may be limited by geography, time, type of road, weather or by some other criteria.

Provisional GB Type Approval: The interim scheme in place of EU whole vehicle type approval since 1 January 2021 following the UK’s exit from the EU. It is expected that in 2022, a comprehensive GB Type Approval scheme will replace the provisional scheme.

Remote oversight: Using connectivity to allow a human to oversee vehicles even if they are not in the vehicle. It refers to tasks conducted by staff while NUIC vehicles are in use, such as identifying unexpected objects and managing emergencies. See Chapter 9.

Risk mitigation manoeuvre: A manoeuvre which is sufficient to reduce the risk of a crash, if the user-in-charge fails to respond to a transition demand. In Chapter 3 we explain that what is sufficient would be set by regulators.

SAE Taxonomy: Society of Automotive Engineers International, J3016 Taxonomy and Definitions for Terms Related to Driving Automation Systems for On-Road Motor Vehicles, It was first published in 2014 and last revised, in collaboration with the International Standards Organisation (ISO), in April 2021.

Safety driver: A person who, as part of their employment, test drives vehicles equipped with driving automation technologies.

Self-driving features: Under the scheme outlined in Chapter 5, the authorisation authority would specify that an ADS feature is self-driving. The authority must be satisfied that the feature can control the vehicle so as to drive safely and legally, even if an individual is not monitoring the driving environment, the vehicle or the way that it drives. Once a vehicle is authorised as having a self-driving feature, and that feature is engaged, the human in the driving seat would no longer be responsible for the dynamic driving task.

Small series type approval: An approval scheme with technical and administrative requirements commensurate with smaller production runs. The UK’s approval authority for small series type approvals is the VCA.

Society of Automotive Engineers International (SAE): A global association of engineers and technical experts in the aerospace, automotive and commercial-vehicle industries. Its taxonomy established six levels of driving automation in technical document J3016.

Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders (SMMT): A trade association representing more than 800 automotive companies in the UK.

Software Update Regulation: UN Regulation 156 on uniform provisions concerning the approval of vehicles with regards to software updates and software update management system E/ECE/TRANS/505/Rev.3/Add.155. It was made under the procedures set out in the UNECE 1958 Agreement (below) and entered into force on 22 January 2021.

Transition demand: An alert issued by an ADS to the user-in-charge to take over the dynamic driving task, communicated through visual, audio and haptic signals, which gives the user-in-charge a transition period within which to respond. Absent a response, the ADS performs a risk mitigation manoeuvre bringing the vehicle to a stop. This term is also used in UN Reg 157 on Automated Lane Keeping Systems, to refer to a “logical and intuitive procedure to transfer the Dynamic Driving Task (DDT) from the system (automated control) to the human driver (manual control)”.

Transition period: The period of time between the start of the transition demand and the time when the user-in-charge is expected to take over the dynamic driving task.

Type approval: Type approval is the confirmation that production samples of a type of vehicle, vehicle system, component or separate technical unit meets specified requirements. The process involves the testing of production samples and the evaluation of the measures in place to ensure conformity of production. Once type approval is given by an approval authority it allows the manufacturer to produce the vehicle type in an unlimited series, providing vehicles continue to meet the specified requirements.

United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE): The organisation was established in 1947 to promote economic cooperation and integration among its member states. The UNECE provides a multinational platform for policy dialogue, negotiation of international legal instruments and development of regulations and norms. It administers the UNECE 1958 Agreement (below).

UNECE 1958 Agreement: An international agreement governing the approval of motor vehicles in 56 countries. It was agreed in 1958 and has since been revised three times. The full title and citation for the third revision is “Agreement concerning the Adoption of Harmonized Technical United Nations Regulations for Wheeled Vehicles, Equipment and Parts which can be Fitted and/or be Used on Wheeled Vehicles and the Conditions for Reciprocal Recognition of Approvals Granted on the Basis of these United Nations Regulations (Revision 3) E/ECE/TRANS/505/Rev.3”. This is referred to in the report as the “revised 1958 agreement”. For the text, see https://unece.org/fileadmin/DAM/trans/main/wp29/wp29regs/2017/E-ECE-TRANS-505-Rev.3e.pdf.

User-in-charge: An individual who is in the vehicle and in position to operate the driving controls while a self-driving ADS feature is engaged. The user-in-charge is not responsible for the dynamic driving but must be qualified and fit to drive. They might be required to take over following a transition demand. They would also have obligations relating to non-dynamic driving task requirements including duties to maintain and insure the vehicle, secure loads carried by the vehicle and report accidents. An automated vehicle would require a user-in-charge unless it is authorised to operate without one. See Chapter 8.

xxii

1.1 The Law Commission of England and Wales and the Scottish Law Commission have

been asked by the Centre for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CCAV) 1to review the law relating to automated vehicles (AVs). This report presents our recommendations for a new regulatory framework to govern the introduction and continuing safety of AVs on roads or other public places in Great Britain (GB).

1.2 By AVs, we refer to vehicles which can drive themselves without being controlled or monitored by an individual for at least part of a journey. They are sometimes also called autonomous vehicles or driverless cars. At the time of preparing this report, automated vehicle technology is in an advanced state of development but has yet to come into common use.

1.3 The possible benefits of this technology are far-reaching. AVs have the potential to improve road safety, give greater independence to people unable to drive, and provide new opportunities for economic growth.2 However, these potential benefits are not inevitable: uncertainty and regulatory barriers can impede innovation. Furthermore, the benefits are balanced by potential risks if things go wrong. Regulation has a central role to play in all these areas: maximising the benefits, reducing the risk of harm being caused by malfunctioning AVs, and providing incentives and space for responsible innovation to flourish.

1.4 This is the first time that the Law Commissions have been asked to develop legal reforms in anticipation of future technological development. We are conscious of many uncertainties about how AVs will develop. The challenge is to regulate at the right time; premature or over-rigid intervention could stifle innovation, but late intervention could jeopardise safety.

1.5 We appreciate the industry’s desire for a clear and certain route to market, so they understand what is required to be able to deploy AVs on GB roads. We hope that our recommendations, once implemented, will provide such a route. At the same time, we are aware that in practice things may turn out to be quite different from how we imagine. Given this level of uncertainty, the theme of flexibility permeates our report.

1.6 Our recommendations aim to keep safety and innovation at the forefront, while also retaining the flexibility required to regulate for uncertain future development. Our recommended legislation leaves more discretion to regulators and future policy makers than might be expected in a more mature industry.

1.7 We have been asked to undertake a review of the regulatory framework for roadbased automated vehicles with a view to enabling their safe deployment. Our agreed terms of reference are set out in full in Appendix 2 and summarised below.

1.8 It is not our role to consider whether vehicle automation is desirable. Instead, our focus has been on legal regulation. In particular, our terms of reference ask us:

To consider where there may be gaps or uncertainty in the law, and what reforms may be necessary to ensure that the regulatory framework is fit for purpose, including but not limited to addressing the following issues:

(1) who is the ‘driver’ or responsible person, as appropriate;

(2) how to allocate civil and criminal responsibility where control is shared between the automated driving system and a human user;

(3) the role of automated vehicles within public transport networks and emerging platforms for on-demand passenger transport, car sharing and new business models providing mobility as a service;

(4) whether there is a need for new criminal offences to deal with possible interference with automated vehicles and other novel types of behaviour; and

(5) the impact on other road users and how they can be protected from risk.

1.9 Driving automation refers to a range of vehicle technologies. At present many technologies support human drivers by facilitating or taking over part of the task (such as advanced cruise control). This report anticipates that in future these technologies will develop to allow vehicles to drive themselves with no human intervention.

1.10 Our terms of reference describe an AV as a vehicle that is designed to be capable of “driving itself”: to operate in a mode, “in which it is not being controlled and does not need to be monitored by an individual, for at least part of a journey”.3 Our focus is therefore on automated driving systems which replace a human driver for at least part of a journey, rather than those which merely offer driving support.

1.11 Driver support technology is already in use and is presenting challenges. Drivers who misunderstand or over-rely on this technology can create significant safety risks.4 Throughout this project, stakeholders have highlighted the need for a clear boundary between technology which merely assists a human driver, and that which enables a vehicle to drive itself without being monitored. This requires consideration of technologies on each side of the boundary.5

1.12 The review only covers “road based” AVs. We have interpreted this to refer to AVs which are used on roads or in other public places. The phrase “roads or other public places” is frequently used in British legislation and is discussed in Chapter 2. 6It includes pavements, but excludes places to which the public do not have access, such as warehouses or quarries.

1.13 We were asked not to look at land use: the provision of roads or how they are used. We therefore do not consider whether there should be new roads or new road infrastructure to accommodate AVs. Nor do we seek to restrict any existing road users exercising their right to use roads or other public places. Our assumption is that AVs will be introduced onto Britain’s existing road network, or something that broadly resembles existing roads.

1.14 We were asked to focus on passenger transport, as distinct from goods deliveries. 7The freight industry has a distinct regulatory framework and specialised stakeholders. We nevertheless welcomed input from the freight industry as we developed our proposals. Most of our recommendations apply to all road vehicles, irrespective of use, and would therefore also apply to freight vehicles. We suggest an additional permit scheme for passenger services in Chapter 10.8

1.15 The following policy areas of AV reform are being led directly by the UK government, and were excluded from our terms of reference:

(1) data protection and privacy;9

(2) theft, cybersecurity and hacking; 10and

(3) land use policy.11

1.16 During the course of this review we have identified some aspects of data protection, theft and cybersecurity which are essential to delivering our reform proposals. These limited elements are included within our recommendations.

1.17 The project has involved three rounds of consultation, with three consultation papers published between November 2018 and December 2020. These are summarised below.

1.18 We published our first consultation paper (“Consultation Paper 1”) in November 2018. We looked at issues that affect all AVs regardless of how they are used. First, we considered how safety can be assured before AVs are placed on the market, as well as safety assurance once they are on the road. Second, we explored criminal and civil liability. Finally, we examined the need to adapt road rules for artificial intelligence.

1.19 We received 178 written responses. The full analysis of responses as well as the individual responses to Consultation Paper 1 are available online.12

1.20 Our second paper (“Consultation Paper 2”) was published in October 2019. It focused on the regulation of Highly Automated Road Passenger Services, or “HARPS”. We coined the term HARPS to encapsulate the idea of a new service. It referred to a service which uses highly automated vehicles to supply road journeys to passengers without the need for a responsible person on board. Such a vehicle would be able to travel empty or with only passengers on board. We considered a national operator licensing scheme for HARPS.

1.21 Our proposals distinguished between passenger services and other types of vehicle which could travel without a responsible person on board (such as freight services or private vehicles). However, many consultees responded that these distinctions were overly complex and difficult to apply in practice. We have consequently simplified our proposals to recommend a single licensing scheme which applies to all vehicles without a responsible human in the vehicle. These recommendations are set out in Chapter 9.

1.22 We received 109 responses to the paper from consultees working in a wide variety of sectors. The full analysis of responses as well as all of the individual responses to Consultation Paper 2 are available online.13

1.23 Our third paper (“Consultation Paper 3”), published in December 2020, set out a regulatory framework for AVs. The proposals included:

(1) distinctive rules for two types of automated driving features:14

(a) those that may require a person (whom we call a “user-in-charge”) to take over driving for part of a journey. An example would be AVs that can only drive themselves on motorways; and

(b) “no user-in-charge” (NUIC) features that can complete a whole journey

without intervention by anyone on board (such as remotely operated ridehailing).

(2) safety assurance regulation, both before vehicles are put onto the market and while they are in use. This involved a shift away from the criminal enforcement of traffic rules towards a new no-blame safety culture.

(3) three legal roles associated with automated driving: AV manufacturers/ developers; users of AVs that are less than drivers but more than passengers (the user-in-charge); and NUIC operators.

1.24 We received 117 responses, which are available on our website. We are especially grateful to all consultees who contributed despite the pressures of COVID-19, whether by providing a written response or giving their views through virtual meetings and conferences. A full analysis of responses is being published alongside this report.15

1.25 The report is divided into 14 chapters:

(1) Chapter 1 is this introduction.

(2) Chapter 2 introduces key concepts. First, we explain the vocabulary associated with driving automation. Second, we outline the new legal actors and regulatory schemes recommended in this report. We then set out a recommendation for a new Automated Vehicles Act and discuss the devolution issues involved. Finally, we look at three overarching themes: equality, accessibility and data.

1.26 Two chapters look at the threshold for when a vehicle should be considered capable of safely driving itself, at least in some circumstances.

(3) Chapter 3 asks what is required for driving automation to cross the legal

threshold from driver assistance to “self-driving”. We recommend a high test for a vehicle to be authorised as having self-driving features: it must be safe even if a human user is not monitoring the driving environment, the vehicle or the way it drives. A user may be required to respond to a clear and timely signal to take over driving (a “transition demand”), but otherwise must not be relied on to respond to events or circumstances.

(4) Chapter 4 considers when an AV is safe enough to be deployed on public roads. The issue divides opinion. While some consultees argued that AVs need only be marginally safer than human drivers, others thought that AVs should be substantially safer to gain public acceptance. We see the issue as one for political judgement. We recommend that the Secretary of State for Transport publishes a safety standard by which the safety of automated and conventional driving should be compared. A new AV in-use regulator would then be responsible for collecting the required data.

1.27 The next two chapters consider how to assure that AVs are safe before they are placed on the market; and how to regulate their safety in-use on an ongoing basis.

(5) Chapter 5 sets out our proposed authorisation scheme and explains its interaction with the existing process for the approval of vehicles. We recommend a process to assess whether a vehicle meets the threshold required to be considered as having self-driving features. The manufacturer or developer putting the vehicle forward for authorisation will need to submit a safety case demonstrating that the threshold for self-driving is met. This entity will also need to show that it is capable of keeping the vehicle safe on an ongoing basis. If so, it will be registered as an Authorised Self-Driving Entity (or ASDE) and subject to regulatory sanctions if things go wrong.

(6) Chapter 6 recommends legislation to establish a new AV in-use regulator, with statutory duties and powers. If an authorised AV breaches traffic rules while driving itself, this will no longer involve criminal prosecution. Instead, the in-use regulator will be given powers to apply a wide range of regulatory sanctions, including civil penalties, improvement notices and (where necessary) suspension of authorisation. The emphasis will be on a learning culture, which prevents problems from recurring.

1.28 It is common for drivers to be confused about driving automation. One particular concern is that marketing might encourage people to believe that driver support features are “self-driving”, even though they have not been authorised under our scheme.

(7) Chapter 7 considers the current regulation of misleading marketing. We conclude that it does not fully address the mischief that drivers using systems that fall short of self-driving may be misled into thinking that they do not need to pay attention to the road. This is dangerous both for them and for other road users. We therefore recommend two new criminal offences, to restrict the use of certain terms (such as “self-driving”) and to prohibit practices which confuse drivers about the need to pay attention.

1.29 The next chapters describe the role of two new legal actors - the user-in-charge and the NUIC operator.

(8) Chapter 8 focuses on the user-in-charge. In simple terms, a user-in-charge is the human in the driving seat while a self-driving feature is engaged. Their main role is to take over driving, either following a transition demand or because of conscious choice. We recommend that a user-in-charge must be qualified and fit to drive. They have some “driver” responsibilities, such as insuring the vehicle and reporting accidents. However, while the vehicle is driving itself, the user-in-charge has an immunity against any criminal offence arising from the performance of the driving task.

(9) Chapter 9 considers vehicles authorised to operate with no user-in-charge (NUICs). We recommend that every NUIC vehicle should be overseen by a licensed NUIC operator, with responsibilities for dealing with incidents and (in most cases) for insuring and maintaining the vehicle.

(10) Chapter 10 considers the additional regulation needed for passenger services using NUIC vehicles, without a driver or user-in-charge. Given the many unknowns in this area, we recommend a new form of interim permit for these services. All such services should involve an element of “co-design” to address issues of accessibility.

1.30 Our aim is to promote a no-blame safety culture that learns from mistakes. We see this as best achieved through a system of regulatory sanctions rather than by replicating the criminal sanctions applying to drivers of conventional vehicles. However, this relies on the honesty and transparency of the ASDE and NUIC operator in sharing information with regulators.

(11) Chapter 11 recommends new criminal offences where an ASDE or NUIC operator misleads regulators or conceals safety-relevant information. We discuss the liability of the entity and its senior managers, and recommend an aggravated offence where a lack of candour leads to a death or serious injury.

1.31 Our terms of reference asked us to consider whether there is a need for new criminal offences “to deal with novel types of conduct and interference”.

(12) Chapter 12 considers criminal offences relating to the ways in which people might interfere with AVs or with road infrastructure. As most forms of interference are already criminal offences, we recommend relatively minor additions.

1.32 A special regime of civil liability relating to vehicles that drive themselves was introduced in the Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018.

(13) Chapter 13 reports on our review of the 2018 Act. We recommend that the listing procedure under section 1 of the Act is replaced by our authorisation procedure. However, on issues of substantive liability, our conclusion is that the 2018 Act is “good enough for now”. It should be reviewed in the light of practical experience.

(14) Finally, Chapter 14 sets out our recommendations to Government.

1.33 The report contains three appendices:

(1) Appendix 1 contains a list of stakeholders we have met and conferences attended throughout the project.

(2) Appendix 2 contains the project’s Terms of Reference.

(3) Appendix 3 relates to Chapter 7. It contains our analysis of the current law on misleading marketing about unauthorised driving automation.

1.34 This report is the culmination of over three years’ work, involving analysis of the current law and wide consultation. To keep the length of this report within reasonable bounds, we focus on setting out our recommendations. Interested readers may wish to look at the following additional material that we are publishing alongside this report:

(1) a 32-page summary and a 4-page overview;

(2) a full analysis of responses to Consultation Paper 3;

(3) an impact assessment setting out the costs and benefits of our recommendations;

(4) Background Paper A, “Who is liable for road traffic offences?”. We originally published this alongside Consultation Paper 1, but we have updated and added to it;

(5) Background Paper B: “The role of the driver in passenger licensing”. This considers how far a driver is integral to existing schemes of private hire, taxi and PSV regulation.16

1.35 For further analysis of existing law, readers are referred to our consultation papers. These include an overview of private hire, taxi and PSV regulation; 17bus regulation;18 vehicle standard regulation;19 and the current law of market surveillance.20

1.36 Our thanks go to all those who took part in the three rounds of consultation, both for participating in consultation events or meeting with us to discuss the consultation papers, and for submitting formal written responses. We have held more than 350 meetings with individuals and organisations contributing to the project, and we are very grateful to them for giving us their time and expertise.

1.37 We include a list of stakeholders we have met and conferences attended during the project in Appendix 1.

1.38 Various staff have contributed to this final report. At the Law Commission of England and Wales the lead lawyers were Jessica Uguccioni, Tamara Goriely and Connor Champ. They were assisted by the following researchers across the Scottish Law Commission and the Law Commission of England and Wales: first by Jagoda Klimowicz, Gianna Seglias, Elizabeth Connaughton and Alison Hetherington; and then by Matthew Timm, Gwen Edmunds and Hannah Renneboog.21

1.39 We would also like to thank Henni Ouahes (Head of Public Law, Law Commission of England and Wales), Charles Garland (lawyer and interim Chief Executive, Scottish Law Commission), Vindelyn Smith-Hillman (Chief Economist, Law Commission of England and Wales), and Douglas Hall (Office of Parliamentary Counsel) for their input during this review.

10

2.1 Many driver support features are currently available to help a human driver. This report anticipates that, in future, these features will develop to a point where a human can use them without paying attention to the road. Instead, an automated vehicle (AV) will be able to drive itself for at least part of a journey. This has profound legal consequences. The human driver can no longer be the principal focus of accountability for road safety. Instead, new systems of safety assurance are needed, both before and after vehicles are allowed to drive themselves on roads and other public places.

2.2 Existing law reflects a division between rules governing vehicle design on the one hand and the behaviour of drivers on the other. This is true at both international level (through the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE)) 22and at domestic level. Legislating for self-driving requires an integrated approach, bridging these two regulatory spheres: the automated driving system (ADS) constitutes equipment fitted in a vehicle, but it also determines the behaviour of the vehicle.23

2.3 To accommodate AVs, we need a new vocabulary, new legal actors and new regulatory schemes. Here we look briefly at each. These new actors and schemes require primary legislation: we therefore recommend a new Automated Vehicles Act. Finally we consider three overarching themes: equality, accessibility and data.

2.4 As with every new endeavour, driving automation has acquired its own specialist language. The Society of Automotive Engineers International (SAE) has pioneered common terms to discuss driving automation through its detailed taxonomy. The SAE Taxonomy is best known for establishing six “levels” of driving automation. As we explain in Chapter 3, we do not tie our recommendations to an SAE level. However, an understanding of SAE levels is needed to participate in wider policy debates and make comparisons across jurisdictions.

2.5 We draw on other concepts used by the SAE, including “dynamic driving task” (DDT) and “operational design domain” (ODD). We explain our use of the words automated vehicle (AV); automated driving system (ADS); ADS feature; and self-driving.

2.6 The SAE first published its “taxonomy and definitions for terms related to driving automation systems for on-road motor vehicles” in 2014. Since then, the taxonomy has been updated several times and has been widely quoted throughout the world. In this report we refer to the latest version, published in April 2021.24

2.7 The SAE Taxonomy describes its purpose as “descriptive and informative, rather than normative”, and “technical rather than legal”.25 Its aim is to provide a common language to discuss driving automation technologies, not to prescribe how they should be regulated.

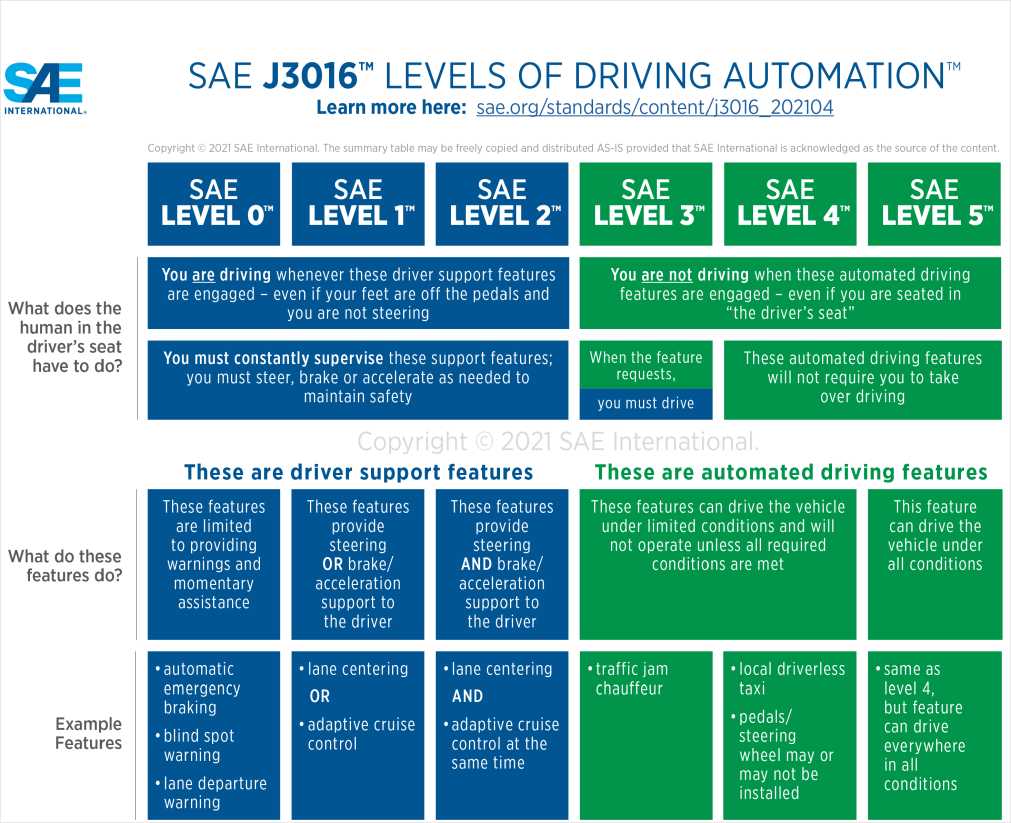

2.8 The SAE summarises the six levels of automation in the following figure:

|

|

Figure 2.1 A simplified visual chart of the SAE J3016 levels (from SAE.org). |

2.9 Note that the SAE use the phrase “driving automation” as a generic word to apply to all levels. However, it makes a crucial distinction between “driver support features” (which must be supervised by a human driver) and “automated driving” (where a human is not driving, even if sitting in the driving seat).

2.10 During previous consultations, we found considerable variation in what people understood each level of automation to cover, even among those working in the field.26

2.11 The most difficult level is “conditional automation” (Level 3), in which the automated driving feature is generally capable of performing all the driving tasks but a human in the driving seat is expected to respond to its “request to intervene”. In SAE terminology, at Level 3, a human “fallback-ready user” must be receptive to the request or to an evident vehicle systems failure but is not expected to monitor the driving environment.27

2.12 Level 3 can be contrasted with Level 4 (high automation). Here, if the user fails to respond to a handover alert the issue is not safety-critical. Instead the system will put the vehicle into a “minimal risk condition”: a stable, stopped condition which reduces the risk of a crash.28

2.13 The SAE does not prescribe legal tests each level must meet. Instead, the levels are based on the designers’ intent. As the Taxonomy states:

As a practical matter, it is not possible to describe or specify a complete test or set of tests which can be applied to a given ADS feature to conclusively identify or verify its level of driving automation. The level assignment rather expresses the design intention for the feature....29

2.14 This report has a different aim. We recommend a regulatory framework to verify whether automated driving reaches the required standard to be treated differently from assisted driving.

2.15 Our tests are not tied to a particular SAE level. In Chapter 3 we recommend that, for an ADS feature to be considered self-driving, the authorisation authority must be satisfied that it can control the vehicle so as to drive safely and legally, even if an individual is not monitoring the driving environment, the vehicle or the way that it drives. The vehicle may issue a transition demand, requiring the human in the driving seat to take over, but the transition demand must be communicated by clear, multi-sensory signals and give the user-in-charge sufficient time to gain situational awareness.

2.16 The SAE Taxonomy defines the core of what “driving” means from a technical perspective. A critical concept is the “dynamic driving task” (or DDT). It has the following key elements:

(1) sustained lateral and longitudinal motion-control of the vehicle: steering, accelerating and braking;

(2) object and event detection, recognition, classification, response preparation and response execution: monitoring the driving environment and reacting to other road users and the conditions of the road.30

2.17 Several “driver support” features, such as advanced cruise control, can steer, accelerate and brake, but cannot respond to all the conditions of the road. These features still require the driver to pay attention and react to other road users and road signs. Without “object and event detection and response”, 31a vehicle cannot carry out the whole dynamic driving task.

2.18 In law, drivers have many responsibilities. Many relate to the way that a driver monitors the driving environment and reacts to it, by (for example) steering and braking. However, the law also imposes responsibilities on drivers which do not relate to dynamic driving. Examples would be holding insurance, maintaining roadworthiness or ensuring that children wear seat belts. 32In this report, we draw a key distinction between dynamic driving offences and other “non-dynamic” offences.

2.19 The operational design domain (ODD) sets out the conditions in which any automated driving system or feature is designed to function. The conditions may relate to anything. They may, for example, relate to a place (such as Milton Keynes); a type of road (such as a motorway); a time of day (such as during daylight); a speed (such as under 60 km per hour); or weather (such as not in snow). 33The ODD is set by the manufacturer and (under our recommended scheme) must be endorsed by the authorisation authority.

2.20 While driving, an ADS may exit its ODD for many reasons: in our examples, the vehicle may leave the motorway, or it might start snowing. When this happens, the system will usually need to issue a transition demand to a human to take over driving or come to a stop. In some cases, the ADS may continue to drive the vehicle at reduced speed until it can stop safely. The latest draft of the SAE Taxonomy acknowledges that during this time, “an ADS may operate temporarily outside of its ODD”.34

2.21 In this report we refer to an automated driving system (ADS); to an automated vehicle (AV); and to an ADS feature. We use these terms as follows:

(1) An automated driving system (ADS) is defined by the SAE as the combination of software and hardware capable of performing the entire DDT.35 ADS refers to a system within a vehicle, not the vehicle itself. A single ADS may operate in different ODDs.

(2) An “automated vehicle” (AV) is a generic term. It refers to a vehicle equipped with an ADS which is able to conduct the entire dynamic driving task in one or more operational design domains. A vehicle may be an AV even if the ADS is not engaged at the time. The term refers to a vehicle which is capable of selfdriving, at least in some circumstances.

(3) An ADS feature is part of an ADS, which is designed to operate in a particular ODD. A single AV may have several ADS features. For example, it may have a motorway feature, allowing the AV to drive itself on the motorway with a user-in-charge. It may also have an automated valet parking feature, allowing it to park itself in some car parks with no user-in-charge. As the SAE describe it:

A given driving automation system may have multiple features, each associated with a particular level of driving automation and ODD.36

2.22 The term “self-driving” is not used by the SAE, who describe it as a “deprecated term”.37 We use the term because it can be given its own specific definition and does not carry other meanings in the SAE Taxonomy. As we explain in Chapter 3, we use it to indicate a legal threshold. Once a vehicle has been authorised as having a “selfdriving” ADS feature, and the feature is engaged, the human in the driving seat is no longer responsible for the dynamic driving task.

2.23 The Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018 refers to vehicles which are capable “in at least some circumstances or situations, of safely driving themselves”.38 In section 8(1)(a), a vehicle is said to be “driving itself” if it is “operating in a mode in which the vehicle is not being controlled, and does not need to be monitored, by an individual”.

In this report we largely endorse this definition, which embeds safety. Before being authorised, the authorisation authority must be satisfied that the vehicle is safe even if an individual is not monitoring the driving environment, the vehicle or the way it drives.

2.24 A difficulty with the term “self-driving” is that it is sometimes used in a confusing way to refer to driver support features. This is not only confusing but dangerous: drivers may be misled into thinking that they do not need to pay attention. In Chapter 7 we recommend that “self-driving” should become a protected term. It should be a specific offence to use it in relation to driving automation which is not authorised as selfdriving.

2.25 Automated Lane Keeping Systems allow a vehicle to steer and control speed within its lane for extended periods. In 2020, the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) agreed a new regulation to approve the use of ALKS on motorwaytype roads. In January 2021, Regulation 157 entered into force in the UK and the other 53 UNECE contracting parties. 39It enables ALKS to receive type approval under the international scheme of vehicle approval described in Chapter 5.40 In December 2021, Mercedes was the first manufacturer to secure approval of an ALKS feature under Regulation 157 from the German type approval authority, KBA. 41Mercedes state that, in the first half of 2022, new cars will be available with a feature which is able to drive in congested situations “on suitable stretches of motorway in Germany”.42

2.26 When first adopted, the ALKS Regulation only applied to passenger cars and vans, and for speeds up to 60km (37 miles) per hour.43 However, the regulation is continuing to evolve. In November 2021 amendments were adopted which extended the ALKS Regulation to heavy vehicles including trucks, buses and coaches. 44This amendment is expected to enter into force in June 2022. The Special Interest Group on UNECE Regulation 157 has been progressing further amendments to the ALKS Regulation, including:

(1) increasing the maximum speed to 130 km (80 miles) per hour;

(2) lane change and minimum risk manoeuvre capabilities; and

(3) standards for “detectable collisions”.45

2.27 In Consultation Paper 3 we used ALKS as a case study for what it means for a vehicle to be able to “drive itself”. We concluded that although the ALKS regulation was “a first regulatory step” towards automated driving, it was up to each jurisdiction decide the civil and criminal consequences of using an ALKS. As we discuss below, our recommended initial safety assurance scheme has two stages; approval and authorisation. Although approval under Regulation 157 is sufficient to meet the first hurdle, an ALKS feature will only be lawfully used in self-driving mode once the vehicle has passed the second authorisation stage.

2.28 One difficulty with understanding driving automation is the complexity and impenetrability of the language associated with it. The crucial distinction between “driving automation” and “automated driving” may not be immediately apparent.46 Acronyms abound: ADS, DDT, ODD. Each concept depends on understanding another concept. One cannot understand the nature of an ADS feature without understanding that it involves a system (the ADS) which can perform the entire DDT in an ODD.

2.29 This makes it difficult to give a succinct and clear message to the public about how to interact with driving automation. Work is being done in this area. For example, Euro NCAP has developed a five-star safety rating system for consumers, to communicate the limitations of driver assist systems available on the market today.47 Furthermore, in September 2019 ABI/Thatcham published a joint document setting out a three-part taxonomy:48

(1) Assisted driving, where the driver remains in charge of the driving task and must constantly monitor the road environment.

(2) Automated driving, where the user-in-charge needs to be available for transition of control, but not to maintain safety.

(3) Autonomous driving, where the vehicle has full responsibility for the dynamic driving task, and the user is effectively a passenger.

2.30 These concepts are similar to the distinctions in this report between driver assistance, user-in-charge features and no user-in-charge features.

2.31 “Automated vehicle” is the term most commonly used for vehicles which are able to carry out the entire DDT. For example, the UK Government adopted the term “automated vehicle” in the Automated and Electric Vehicles Act 2018 and in its subsequent codes of practice.49 We hope that, in time, the term will become better understood.

2.32 We do not recommend use of the term “autonomous” in legislation. Philosophers use the term to refer to acting in according with “reasons, values, or desires that are authentically one's own”. 50Vehicles do not have values or desires of their own, so describing them as “autonomous” may be unduly anthropomorphic. On a more practical level it may also underestimate the degree to which vehicles with no humans in the driving seat may still rely on human assistants in remote operation centres, as discussed in Chapter 9.

2.33 However, unlike the SAE, we do not “deprecate” use of the term “autonomous”. 51We have adopted terms such as “self-driving” which allow us to make legal distinctions without undue confusion. However, we accept that we are at the beginning of a long road in understanding driving automation, and how to communicate its many nuances to the public. The fact that a word is used in statute should not prevent other attempts to communicate. One particular suggestion is that self-driving status may be indicated by a logo, or kite mark or even a colour.52

2.34 Our recommendations apply to the use of AVs on roads or other public places in Great Britain. The terms “road” and “other public place” are widely used in road traffic legislation. 53They have been interpreted many times by the courts, both in England and Wales and in Scotland. In Consultation Paper 3, we looked in detail at this case law.54

2.35 Essentially a road is a way by which travellers may move from place A to place B and to which the public have access. 55Access is not simply about motorised access: if, for example, members of the public are allowed to go for a walk or exercise their dogs on a university campus road, that road falls within road traffic legislation. 56Furthermore, the public do not necessarily have to have a clear right to use the road, provided that they do use it as a matter of fact and that use is permitted, either expressly or implicitly.57

2.36 Similarly, a public place is a place which is actually used by the general public, without objection by the landowner or occupier. 58So, for example, where a car park is open to the public, the marked lanes used to reach bays are “roads”, while the bays themselves are “other public places”.

2.37 Our recommendations do not apply to restricted environments, such as private car parks, ports, quarries or warehouses. For these restricted environments, the Health and Safety at Work etc Act 1974 and occupiers’ liability appear to provide a sufficient legal framework. By contrast, places which allow public access are considerably more challenging for AVs and require new forms of regulation.

2.38 As we said in Consultation Paper 3, roads may be used by many people, in different ways, for different purposes, at the same time. This leads to a complex environment, with an almost infinite number of scenarios, not all of which are controlled by clear rules. At a political level, competing public pressures lead to constant readjustment of how road space is allocated, whether through new junction layouts, wider pavements, new bus or cycle lanes or changes to the Highway Code. From 2016 to 2019, the Highway Code was changed 14 times. Further major changes to prioritise vulnerable road users will be introduced on 29 January 2022 if approved by Parliament.59 Traditional systems of vehicle approval focus on assessing vehicles before they are placed on the road. However, the frequent changes to road rules mean that AVs will require much greater monitoring while they are in use to ensure they can deal with (changing) road rules.

2.39 We have worked on the assumption that all road users who currently have access to roads will continue to do so. We do not propose that any existing road users should have their freedom to use the road restricted to make way for AVs.

2.40 At present, most legal responsibilities for driving fall on a human driver. In the absence of a driver, these responsibilities need to be fulfilled in other ways. In this report, we recommend three new legal actors. We refer to these as the Authorised Self-Driving Entity (ASDE), the user-in-charge and the NUIC operator.

2.41 An ASDE is the vehicle manufacturer or software developer who puts an AV forward for authorisation as having self-driving features. The ASDE must register with the authorisation authority60 as the first point of contact if things go wrong. Our proposals retain some flexibility over the identity of the ASDE: it may be a vehicle manufacturer, or a software developer, or a partnership between the two. However, the ASDE must show that it was closely involved in assessing the safety of the vehicle. It must also have sufficient funds to respond to regulatory action and to organise a recall.61

2.42 The ASDE will be responsible for vehicles which are driving themselves on GB roads. Problems will be reported to the in-use regulator. The aim of the in-use regulator is to promote learning from mistakes and make improvements for the future. It will have power to apply a range of regulatory sanctions to the ASDE for breach of road rules, including compliance notices and civil penalties.

2.43 In Consultation Paper 3 we referred to the entity that puts an AV forward for authorisation as the Automated Driving System Entity or ADSE. Consultees pointed out that this was the wrong name: the entity should not simply take responsibility for the automated driving system (ADS) but for the safety of the vehicle as a whole. Consultees told us that it was not possible to distinguish the safety of the system from the safety of the vehicle. In the light of consultees’ concerns, we have changed the name. We have therefore replaced the old term, Automated Driving System Entity (ADSE), with the new term, Authorised Self-Driving Entity (ASDE). For the sake of simplicity, we refer to an ASDE throughout this report, even where we report on previous consultations that used the earlier term.

2.44 The user-in-charge can be thought of as a human in the driving seat while a vehicle is driving itself. We define a user-in-charge as an individual who is in the vehicle and in a position to operate the driving controls while an ADS feature is engaged. 62We recommend that every self-driving vehicle should have a user-in-charge, unless the ADS feature is specifically authorised for use with no user-in-charge.

2.45 The user-in-charge must be qualified and fit to drive, as they may be called on to take over driving if the ADS issues a transition demand. While the ADS feature is engaged, the user-in-charge is not responsible for dynamic driving. They do not control the vehicle through steering, accelerating or braking, and do not need to monitor the driving environment.63 They cannot be held liable for criminal offences which arise from these activities.

2.46 However, a user-in-charge does retain other driver responsibilities. Like a driver, a user-in-charge must (for example) insure the vehicle and check that any load is secure before they set off. During a journey they must ensure that any children in the vehicle are wearing their seatbelts. Following an accident, they should exchange insurance details and report the matter to the police in accordance with section 170 of the Road Traffic Act 1988. They are also required to pay any tolls and charges and check that the vehicle is legally parked before they leave it.

2.47 Some features will be authorised for use without a user-in-charge. We refer to these as “No User-In-Charge” (NUIC) features. We recommend that when a NUIC feature is engaged on a road or other public place, the vehicle is overseen by a licensed NUIC operator.

2.48 A licensed NUIC operator is an organisation rather than an individual. It will need to meet rigorous competence requirements, as discussed in Chapter 9. While a NUIC feature is engaged, the operator will be required to have “oversight” of the vehicle. This does not mean that they need to monitor the driving environment. If a driving automation system requires an individual to monitor the driving vehicle, it is not selfdriving but is simply being driven remotely. However, NUIC operator staff will be expected to respond to alerts from the vehicle if it encounters a problem it cannot deal with, or if it is involved in a collision. The SAE Taxonomy refers to these functions as “remote assistance” and “fleet operations”. 64It is not absolutely essential that this is done remotely through screens. It is possible that staff might be physically present in a limited area, such as a car park. However, we anticipate that in the great majority of cases, a NUIC operator will employ staff in a remote operations centre, with the many challenges this involves.

2.49 The ASDE and NUIC operator could be the same organisation, as where a manufacturer or developer also provides a passenger service. If so, it may submit a combined safety case to the authorisation authority and obtain both ASDE status and a NUIC operator licence at the same time. However, it will also be possible for the two roles to be carried out by different entities.

2.50 The figure on the following page provides a brief overview of how these actors fit together.

ASDE

Needed for all on-road AVs. Puts the AV forward for authorisation as having self-driving features and is legally responsible for the performance of the AV. Responsible for the safety case. Must be of good repute, and have appropriate financial standing in the UK.

2.51 In this report we recommend that the UK Government should publish a safety standard against which the safety of AVs can be measured. The safety standard should inform three new regulatory schemes. These deal with initial authorisation before vehicles are allowed on GB roads (beyond trials); in-use regulation; and NUIC operator licensing.

2.52 In Chapter 4 we consider the standard of safety that AVs should reach before being deployed on roads and other public places. We note a range of views, from those who think that it is sufficient for AVs to be marginally safer than average human drivers, to those who think that AVs should be considerably safer.

2.53 We conclude that the issue is one for political judgement. We recommend that legislation should require the Secretary of State for Transport to publish a safety standard against which the safety of AVs can be measured. This standard should include a comparison with human drivers. In exercising their functions, the authorisation agency and in-use regulator should have regard to the published standard.

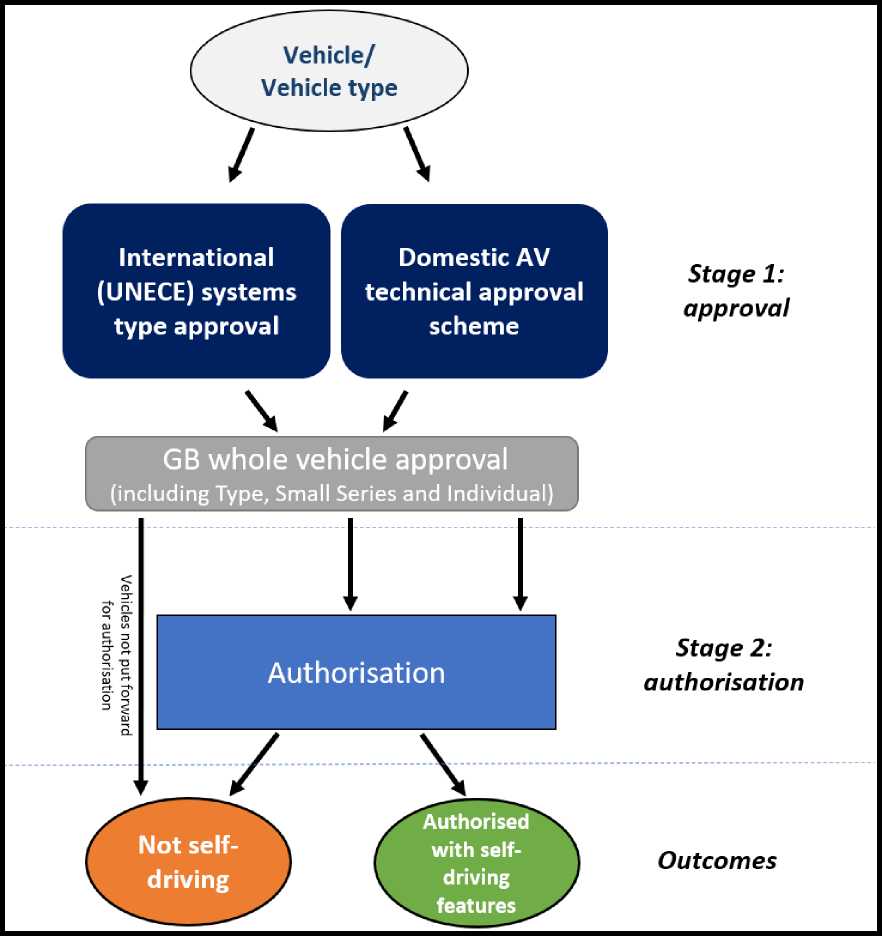

2.54 As with all road vehicles, an AV will be required to receive approval before it can be registered. Typically, approval involves separate approvals for systems and components followed by whole vehicle approval, for the vehicle as a whole. Approval can be given to a “type” of vehicle so that it can be produced in a small or an unlimited series. Alternatively, the UK also operates a scheme to approve individual vehicles.

2.55 Following the UK’s departure from the EU, Great Britain acquired more control over the way in which vehicles are approved. In this report, we recommend that manufacturers who wish to include an ADS in their vehicles should have a choice. They may obtain systems approval at international level, in accordance with a UNECE regulation, from any UNECE approval authority. Alternatively, they can apply for domestic approval under a new domestic AV technical approval scheme. In either case, the whole vehicle will need to receive the new GB whole vehicle approval that has replaced EU whole vehicle approval for most motor vehicles.65

2.56 Once a vehicle has been approved, it may be placed on the market, but it is not authorised to drive itself. We recommend that, before a vehicle is regarded as selfdriving, it should undergo a second “authorisation” stage.

2.57 Authorisation is new. While national or international vehicle approval is largely concerned with technical issues (verifying and validating systems against specifications), the authorisation decision considers the vehicle and its manufacturer or developer more widely.

2.58 The authorisation authority will assess whether a vehicle has ADS features which reach the threshold for self-driving recommended in Chapter 3. The authorisation authority must be satisfied that each specified ADS feature can control the vehicle so as to drive safely and legally, even if an individual is not monitoring the driving environment, the vehicle or the way that it drives. The authorisation authority must decide whether the ASDE has sufficient skill and financial resources to keep the vehicle up-to-date and compliant with traffic laws in Great Britain and deal with any problems that arise.

2.59 Once the authorisation authority is satisfied that all is in order, it will do three things. First, it will authorise the vehicle as a whole as equipped with an ADS feature capable of self-driving. Secondly, it will specify each ADS feature within the vehicle, describe the ODD and prescribe whether it can be used with or without a user-in-charge. Thirdly, it will register an entity as the ASDE.

2.60 Consultees stressed to us that one cannot look at an ADS in isolation. An ADS is only safe if it is embedded safely within a vehicle. Under our scheme it is the vehicle that is authorised, not the ADS. However, it would be wrong to describe a vehicle as “selfdriving” if it can only drive itself in limited ODDs. In most cases it will be the ADS feature, rather than the vehicle, which is self-driving. Under our scheme, a vehicle will be authorised as having self-driving features.

2.61 The legislation will not name a specific organisation as the authorisation authority. As is common with road traffic legislation, the regulatory powers will be exercised, and duties performed, in the name of the Secretary of State for Transport and allocated to an appropriate Department for Transport agency. However, we would envisage that initially the authorisation authority would be the Vehicle Certification Agency (VCA), which currently grants GB type approval.

2.62 Throughout this project, we have emphasised the importance of on-going safety assurance for AVs. With changes to road rules and the driving environment, and updates to available software and technology, AVs will require continuous regulatory oversight to assure that they achieve a suitable standard of safety throughout their lifetime.

2.63 To support this, we recommend that legislation creates the new role of an in-use safety regulator, with a new set of statutory powers and responsibilities. The overall objective of the regulator is to ensure the continuing safety and legal compliance of self-driving vehicles while they are in-use by learning from mistakes and preventing their re-occurrence. To this end it will:

(1) evaluate the safety of automated driving compared with conventional driving;

(2) investigate road traffic infractions; and

(3) ensure that ASDEs provide sufficient information to users.

2.64 These responsibilities will be supported by powers to apply regulatory sanctions, including informal and formal warnings, compliances orders, civil penalties and in extreme cases, suspension or withdrawal of authorisation.

2.65 Again, the legislation will not name a specific organisation: the powers and duties will be exercised in the name of the Secretary of State for Transport. However, we would envisage that initially the in-use safety regulator would be the Driver and Vehicle Standards Agency (DVSA), which (among other things) is currently responsible for market surveillance and vehicle recalls.

2.66 Where a vehicle drives itself with no user-in-charge, considerable responsibilities will fall on the operator. To obtain a licence, a NUIC operator will need to submit a safety case to show how it will operate vehicles safely without a user-in-charge or driver. It will need to demonstrate how it will maintain connectivity; provide suitable equipment; train and supervise staff; and combat problems of boredom and inattention.

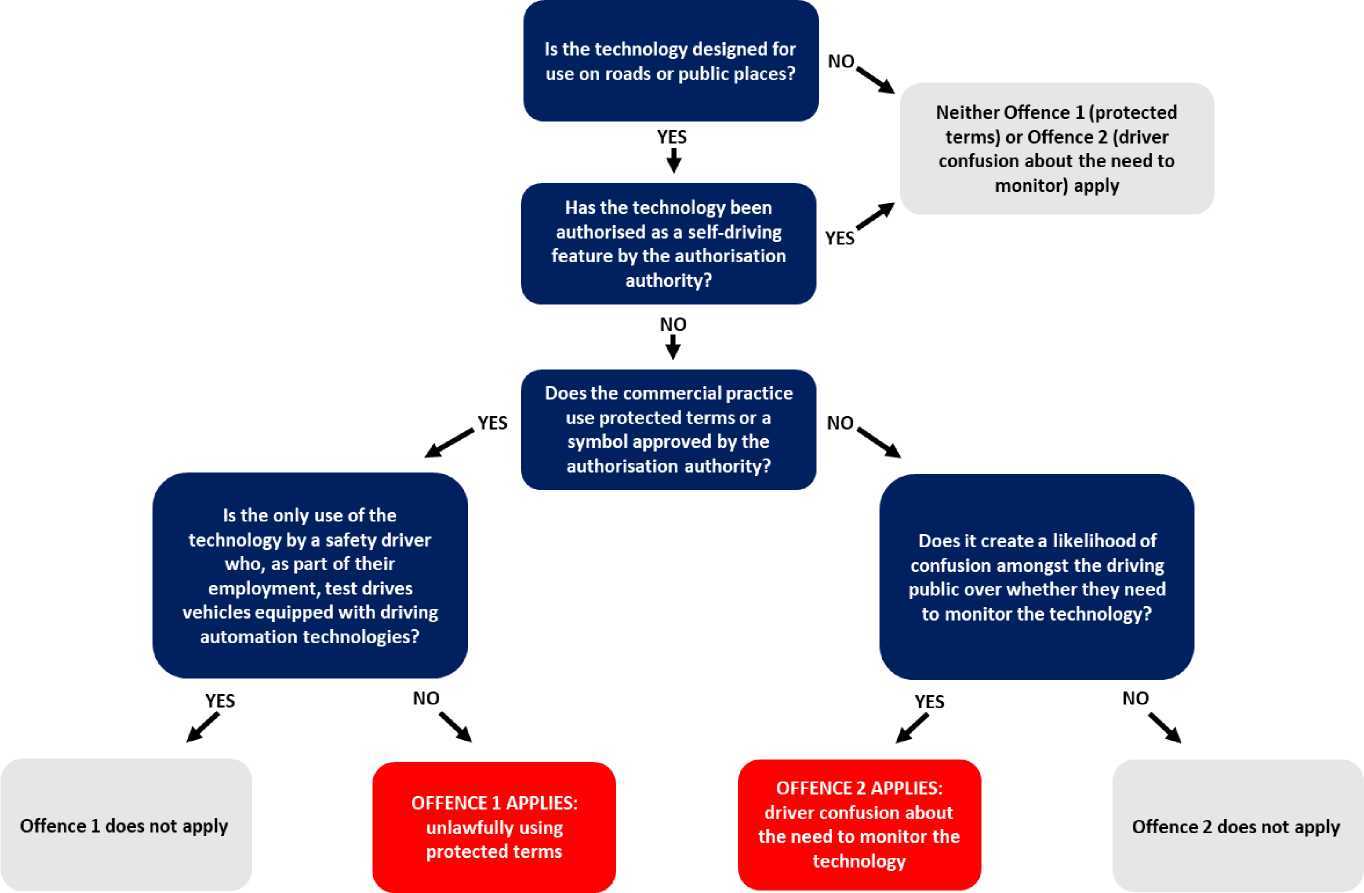

2.67 Initially, we anticipate that an ASDE may wish to operate its own vehicles. We have therefore designed a system where the ASDE and NUIC operator roles can be combined without undue bureaucratic duplication. We recommend that where the ADSE and NUIC operator are the same entity, the entity may submit a joint safety case to be assessed by the authorisation authority. It will also be possible for the NUIC operator to be separate from the ASDE. If so, the ASDE will need to set out what is required for the safe operation of its vehicles, and the NUIC operator will need to show how it meets the operational requirements.