[New search]

[Printable PDF version]

[Help]

FIRST DIVISION, INNER HOUSE, COURT OF SESSION

[2021] CSIH 44

CA46/19

Lord President

Lord Menzies

Lord Doherty

OPINION OF LORD CARLOWAY,

the LORD PRESIDENT

in the Reclaiming Motion by

BAM TCP ATLANTIC SQUARE LIMITED

Pursuers and Reclaimers

against

(FIRST) BRITISH TELECOMMUNICATIONS PLC; AND (SECOND) FIRLEIGH LIMITED

Defenders and Respondents

_______________

Pursuers and Reclaimers: Dean of Faculty (Dunlop QC), Garrity; Morton Fraser LLP

First Defenders: Massaro; Shepherd & Wedderburn LLP

Second Defenders: Moynihan QC; Russel Aitken LLP (on behalf of Miller Samuel Hill Brown

LLP, Solicitors, Glasgow)

20 August 2021

Introduction

[1]

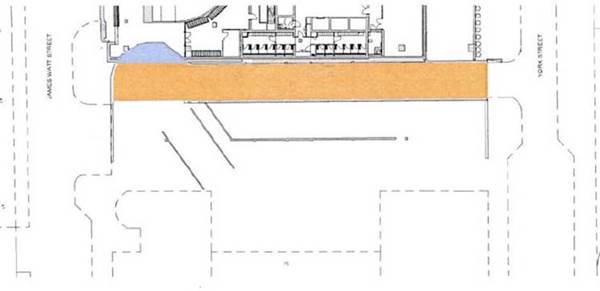

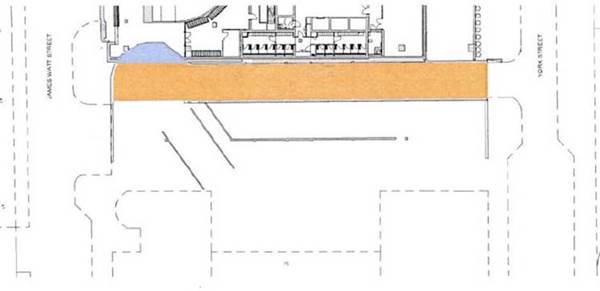

The pursuers seek a declarator that: (1) they are the sole and exclusive heritable

proprietors of a vehicular access ramp leading from York Street, Glasgow to the

underground car park at Atlantic Quay, Broomielaw, Glasgow and the associated turning

circle all as shown tinted ochre on a plan annexed to the summons; and (2) the York Street

2

Ramp and the turning circle at the foot of the York Street Ramp are not, and never have

been, the common property of the pursuers and the first defenders.

[2]

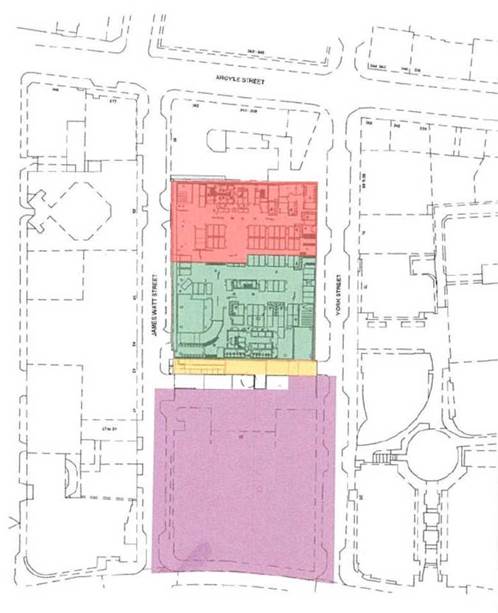

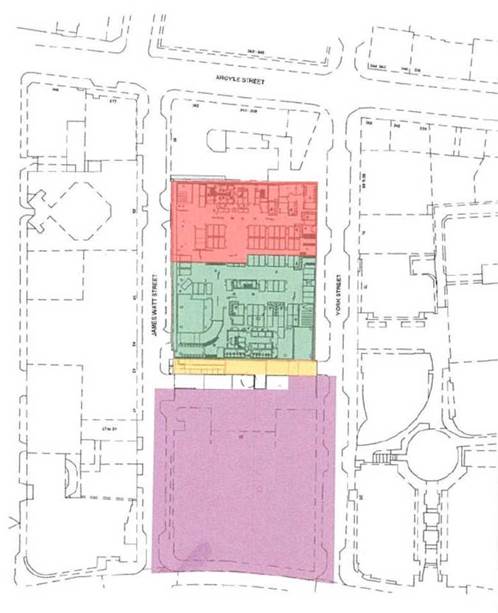

The plan shows the following:

[3]

For introductory purposes, the pursuers own the red (northern) portion of what are

now office blocks which lie between the Broomielaw and Argyle Street to the south and

north and between York and James Watt Streets on the east and west. They are also still the

owners of the green (central) section, but have disponed this to Legal and General Pensions

Ltd. The first defenders own the purple (southern) section. Both red and green areas are

3

shown together "edged red" on a cadastral plan attached to the pursuers' title sheet. This

red etched area includes the yellow (ochre) section between the purple and green areas.

This area contains a ramp which leads from York Street down towards a basement car park.

The pursuers maintain that they are the exclusive owners of this area; standing the terms of

their title sheet.

[4]

The first defenders maintain that the ramp is common property in which they have a

one-half pro-indiviso share. This is what the disposition of the land to them states. In so far

as the pursuers' title sheet differs from this, they say that it is manifestly inaccurate. The

issue is whether the pursuers' title sheet ultimately prevails over the first defenders' earlier

title sheet and the terms of their disposition; all of which refer to a Deed of Conditions. The

Deed predates the building of the office blocks, but it describes what were to be the ramps as

they were to be built upon the common parts.

The Titles

The Deed of Conditions

[5]

Pardev (Broomielaw) Ltd owned a substantial parcel of land to the north of the

Broomielaw in Glasgow. The land was bounded by Argyle Street on the north, and York

and James Watt Streets respectively to the east and west. In June 1997, Pardev registered a

Deed of Declaration of Conditions, dated 29 April 1997. This stated their intention to

develop the land in two phases. The Deed's stated purpose was to set out various burdens

and conditions to which the subsequent owners, of what is described as the Phase I and

Phase II land, would be subject. These would be incorporated into the subsequent

dispositions by reference to the Deed rather than repeated ad longum.

4

[6]

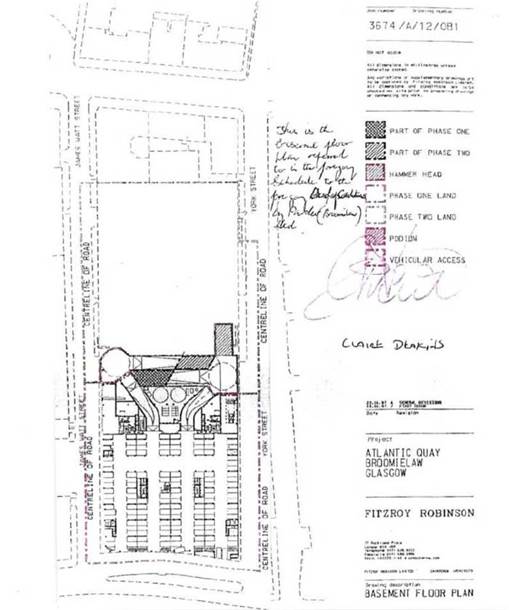

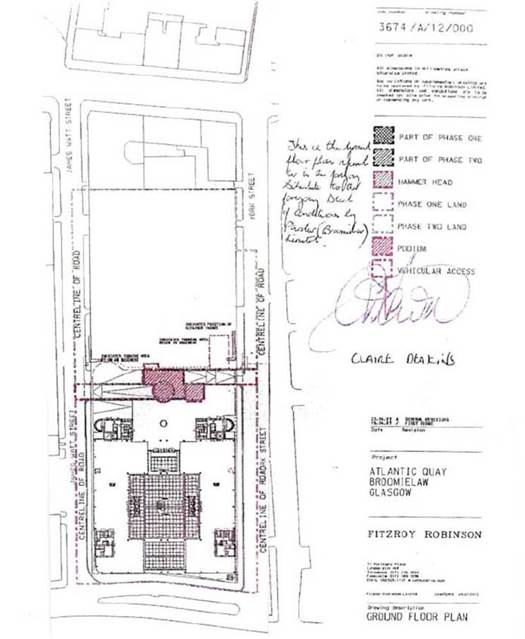

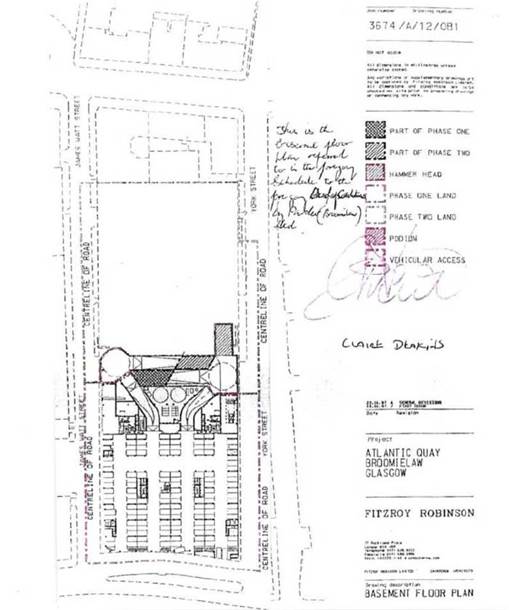

The Deed is bedevilled with defined terms. The Phase I land is the southern part of

the site. It is shown outlined in blue on two plans (basement and ground) attached to the

Deed as follows:

5

[7]

Although relatively indistinct as reproduced, the blue line encloses at ground floor

level the purple area shown on the plan lodged by the pursuers (see para [2]). The line on

the basement plan is slightly different, but the important feature is that the delineated area

does not encroach on the common parts. The common parts are expressly excluded from

the Phase I land. The Phase II land is the rest of the site (ie excepting the Phase I land and

the common parts). It is outlined in green on the plans. The green outline encompasses the

red and green areas on the pursuers' plan. It too does not envelop any of the common parts.

6

[8]

The common parts are defined as including a podium and vehicular access. They

were to "be owned in common" by the Phase I and II proprietors. The podium was to be a

raised platform above the access at ground floor level. It is shown hatched red on the

ground floor plan. Vehicular access "means those structures to be constructed pursuant to

the Works" and to be comprised, inter alia, of two ramps, including their turning circles,

from ground level at York Street and James Watt Street down to the basement areas. The

access is shown "indicatively outlined in red but unhatched" on the Deed's plans. The red

line on the basement plan encompasses both turning circles. The areas underneath the York

Street and James Watt Street ramps were not to form part of the common parts, but they

would respectively be part of the Phase II and Phase I land. These areas are shown hatched

and cross hatched on the basement plan. The James Watt Street ramp included a

"Hammerhead", which was an area hatched in green on the basement plan and was to be

used for Heavy Goods Vehicle access. The ground floor plan delineates the turning circle

and hammerhead underneath. The red delineated common parts appear at all times to be

outside the green (Phase II) and blue (Phase I) land. The "Works" were to be carried out to

form the common parts in accordance with "approved drawings" and the Deed.

The Disposition to, and title sheet of, the first defenders

[9]

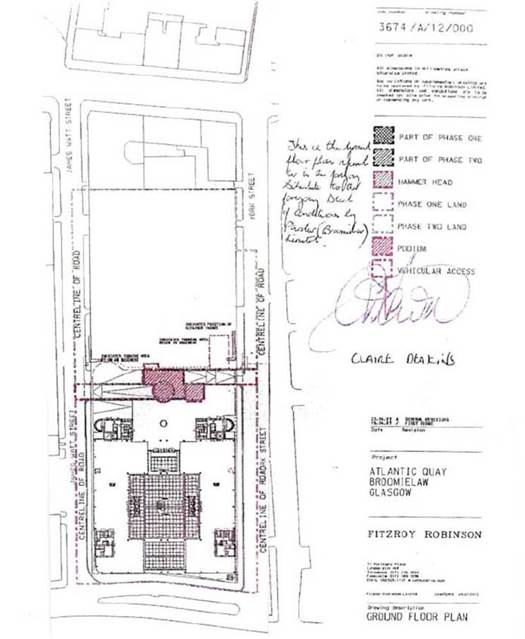

In April 1997 Pardev disponed the Phase I land to the first defenders. The land was

the subject of a general bounding description under reference to a red delineation on two

plans of the ground and basement floors. The two plans are the same as those annexed to

the Deed of Conditions, but they do not have the same annotations. Also conveyed were the

"whole rights, common, mutual and exclusive pertaining thereto as specified in the Deed

7

...". The conveyance was conversely subject to the "whole burdens, conditions, reservations

and others specified as referred to in" the Deed.

[10]

The first defenders' title sheet (as updated) is dated 2005. It obviously pre-dates the

Land Registration etc. (Scotland) Act 2012. The sheet describes the subjects as being within

land edged in red on the title plan. This is a description of the whole of the Phase I and II

lands. The sheet states that the subjects are shown edged in red at ground and basement

levels as shown in Supplementary Plans 4 and 5. These plans show identical building

configurations for the ground and basement floors. In each plan the York Street ramp and

turning circle are shown. The red edged area includes the Phase I land but not the common

parts. However, the description states that the subjects include "the rights specified in the

Deed", which is repeated in the burdens section ad longum. The title includes

Supplementary Plan 1, which is an enlarged section of the basement plan in the Deed, and

with the same annotations (but moved to a different part). Supplementary Plan 3 is an

enlarged version of the ground floor plan in the Deed with the same annotations (but on a

different part). Both plans thus delineate the podium and the vehicular access as being

common parts.

The pursuers' title sheet

[11]

In October 1999 Pardev conveyed the Phase II land to the pursuers' predecessors in

title. The pursuers acquired their title in April 2002. Their title sheet (as updated) is dated

2017, which post-dates the 2012 Act. The disposition to the pursuers is, curiously, not

produced. At that time the first defenders' office block and the York Street ramp had been

built. According to the title sheet, the subjects are "edged red" on a cadastral title plan. The

area enclosed by the red edge includes the common parts and an area under the James Watt

8

ramp which was part of the Phase I land, but this mauve hatched area is "not included in

this Title". Part of the James Watt Street ramp, including most of its turning circle, and a

section of podium, are not included. The title plan states "see supplementary plan(s)".

These include the Supplementary Plans 1 (basement) and 3 (ground) which are attached to

the first defenders' title sheet. As already noted, these supplementary plans delineate the

podium and the vehicular access, including the turning circles, all of which the Deed

describes as the common parts. The burdens section incorporates ad longum the terms of the

Deed of Conditions.

[12]

By disposition dated 26 January 2018, the pursuers purported to convey ownership

of the green area in the pursuers' plan (para [2] above) to Legal and General Pensions Ltd.

The disposition, which is also not produced, is said to include a section of the turning circle

at the bottom of the York Street ramp together with a pro indiviso share in the remainder of

the ramp in common with the pursuers, but not the first defenders. L&G have applied to the

Lands Tribunal for a variation of what they describe as the first defenders' servitude right

over the ramp.

[13]

The pursuers maintain that they are the sole and exclusive heritable proprietors of

the York Street ramp and that the ramp is not common property. Notwithstanding the

terms of, and plans in, the Deed of Conditions, they argue that the first break-off disposition

of the Phase I land in the first defenders' favour, which was registered on 2 July 1997, did

not convey to the first defenders a one-half pro indiviso share of the common parts.

[14]

The practical implications of the dispute arise out of the pursuers' development of

the Phase II land. This is to include a car park underneath the building on that land. The

pursuers have divided that land by selling part of it to L&G but retaining a pro indiviso share

with them in most of the York Street ramp (in yellow), which is now discontiguous with the

9

land which the pursuers continue to own. On the pursuers' plan (para [2] above), there is

now no discernible turning circle at the bottom of the York Street ramp. The reason for that

is that the pursuers have built a wall across the northern part of the circle. They have

purported to dispone the area, which is now cut off by the wall, along with the green area, to

L&G. The Keeper has not yet registered that disposition. Although the pursuers, pending

registration, assert their sole and exclusive ownership of what is shown as the yellow and

grey areas on the following plan, they acknowledge that, on their interpretation of the 1997

disposition, a servitude right of access over the York Street ramp (inclusive of the walled off

section) has been granted to the first defenders.

Legislation

[15]

Section 3(1) of the Land Registration (Scotland) Act 1979 introduced the so-called

Midas Touch

1

, whereby registration of an interest in land in the Land Register would create

a real right which might, unknown to another person with a registered interest, extinguish

existing rights. The section has been described as "mystifying in its opaqueness (sic)" (Reid

1

Scottish Law Commission Discussion Paper No. 125 on Land Registration: Void and Voidable Titles

para 5.34.

10

and Gretton: Land Registration para 2.7). Registration vested the interest as a real right,

"subject only to the effect of any matter entered in the title sheet of that interest under

section 6 of this Act so far as adverse to the interest or that person's entitlement to it ...".

[16]

In terms of section 9(3) of the 1979 Act, the Keeper was empowered, or could be

ordered by the court or the Lands Tribunal, to rectify an inaccuracy in the Land Register. If

rectification "would prejudice a proprietor in possession" she could only do so if:

"(iii) the inaccuracy has been caused wholly or substantially by the fraud or

carelessness of the proprietor in possession; ...".

[17]

The 2012 Act created (ss 80-85) a new, and easier, system of rectification. If an

inaccuracy in a title sheet or in the cadastral map is manifest, the Keeper must rectify it.

[18]

There was no definition of "inaccuracy" in the 1979 Act. One is provided in the 2012

Act (s 65), but it does effect the position under the earlier legislation. A title sheet or

cadastral map is inaccurate if, inter alia, it "wrongly depicts or shows what the position is in

law or in fact".

[19]

The 2012 Act (sch 5, para 19(2)) repealed the Midas Touch, subject to transitional

provisions. Inaccuracies, which existed before the designated day of 8 December 2014 (s 122

of the 2012 Act and the Land Registration etc. (Scotland) Act 2012 (Designated Day) Order

2014, art 2) and which the Keeper had the power to rectify (1979 Act, s 9), are to be treated as

having been so rectified (2012 Act, sch 4, para 17). If there was no rectifiable inaccuracy,

then the Land Register stands (ibid, para 22). In applying section 9(3) of the 1979 Act when

operating these provisions, there is a rebuttable presumption that a registered proprietor

was in possession of the land (ibid, para 18).

[20]

Section 1 of the Prescription and Limitation (Scotland) Act 1973 provides that, if land

has been possessed by any person for a continuous period of ten years openly, peaceably

11

and without judicial interruption, and the possession was founded on the recording or

registration of a deed which is habile to constitute a real right in the land then, as from the

expiry of that period, the real right is exempt from challenge.

The commercial judge's reasoning

[21]

Before the commercial judge, the pursuers moved for decree of declarator in terms of

their first conclusion. The defenders moved for absolvitor, which failing a proof before

answer. The pursuers advanced two propositions. First, whatever the terms of the Deed of

Conditions, the disposition by Pardev to the first defenders did not convey a real right of

ownership in the York Street ramp. The first defenders relied on their disposition as

disponing that right of ownership. If their title sheet did not now reflect this, then the 2012

Act granted them that right because this was a rectifiable inaccuracy. Even if the 1997

disposition did not convey ownership, or that real right had been extinguished in 2002, its

terms constituted a title habile to permit the application of prescription. The pursuers'

second proposition was based on the Midas Touch principle in the 1979 Act. They had

acquired sole and exclusive ownership upon registration of their title in 2002. This

extinguished the first defenders' pro indiviso ownership.

[22]

The commercial judge made avizandum on 29 October 2019. In her opinion of 29 May

2020 she refused to grant the declarator sought. The reasons for her decision were framed as

an analyses of, and answers to, eight self-posed questions. First, the Deed of Conditions set

out an intention that the York Street ramp would be the common property of the Phase I and

II proprietors. Secondly, although the ramp was outside the area delineated in red on the

two plans annexed to the first defenders' disposition, the parts and pertinents clause was

sufficient to convey the real right of common ownership which was referred to in the Deed.

12

Thirdly, the first defenders' title sheet included that right, having regard to the contents of

the property section, the title plan and the supplementary plans. The answer to the fourth

question, on the effect of the registration of the pursuers' land in 2002, depended on whether

the rights in the pursuers' and first defenders' title sheets were inconsistent. They were

inconsistent. There was no reference to the Deed in the pursuers' title sheet that was

relevant to trigger the qualification of a matter adverse to their interest in the land. That

meant that the pursuers acquired a real right of sole and exclusive ownership of the

common parts, by operation of the Midas Touch. Whether this remained the case depended,

fifthly, on whether there was a bijural inaccuracy as at the designated day that, sixth, was

rectifiable. There was a bijural inaccuracy; the pursuers' title was a non domino in relation to

the first defenders' share of ownership in the common parts. The inaccuracy was in

principle rectifiable as knowledge of the terms of the Deed put the pursuers and their

predecessors in bad faith. Whether it could be rectified was, seventhly, a matter for proof on

the defenders' averments which sought to rebut the presumption that the pursuers were a

proprietor in possession. Eighthly, even if the first defenders' real right had been

extinguished, their title, which derived from the 1997 disposition, was habile to found

possession for the purposes of prescription. Proof was required on the averment that the

first defenders had been in possession for the required length of time.

Submissions

Pursuers

[23]

The first defenders' averments about possession were irrelevant. They had not

acquired any ownership rights in the common parts in 1997. This resulted either from the

wording of the disposition and/or the de praesenti principle. The latter had not been relied

13

upon before the commercial judge. That was the end of the matter. If it were otherwise, the

defenders still had to rely on the bad faith of the pursuers to counter the Midas Touch.

There were no relevant defences to that effect. If that simple answer was not accepted, the

court would have to decide (cf Reid and Gretton, Conveyancing: what happened in 2020? at

126-127) whether the inaccuracy had passed through every successor in title up to the

pursuers, or whether it had been "washed out" when the Phase II land was sold by the

person who had purchased it from Pardev in 1999.

[24]

The 1997 disposition did not, and was not habile to, dispone a pro indiviso ownership

in the York Street ramp. The subjects were described by a dispositive clause which referred

to two plans. The ramp lay outwith the boundary description. A proprietor could hold only

incorporeal rights outwith the boundary (Gordon & Wortley: Scottish Land Law (3

rd

ed) I,

para 3.03-07). Possession could not confer title outwith the boundary (Johnston, Prescription

and Limitation (2

nd

ed), para 17.45).

[25]

The commercial judge erred on the dispositive effect of the parts and pertinents

clause in the 1997 disposition. The phrase "pertaining thereto" referred back to the

bounding description, which did not encompass the common parts. The first section of the

clause could not be read as disponing something outwith the boundary. Even if that had

been the intention, the "Works", ie the relevant structures, did not exist at the time of the

registration of either the Deed or the disposition. They were described in the Deed in

aspirational, flexible and malleable terms, such as by reference to "Approved Drawings"

that had to be agreed. The plans were indicative only. As such, no valid conveyance could

have taken place. Real rights could only operate de praesenti. This rendered invalid any

conveyance of land ascertainable only by reference to an uncertain future event (PMP Plus v

Keeper of the Registers of Scotland 2009 SLT (Lands Tr) 2, paras 30-32; Miller Homes v Keeper of

14

the Registers of Scotland 2014 SLT (Lands Tr) 79, paras 55-61 and 64). The drawings were not

only referable to the podium works. The final layout of the vehicular access was subject to

change.

[26]

Even if the first defenders' title was habile to be acquired through positive

prescription, the defenders' case, that there was a rectifiable inaccuracy, rested wholly on

bad faith. That the dispositions in favour of the pursuers or their predecessors may have

been a non domino was irrelevant without bad faith (Reid & Gretton (supra); Stair Memorial

Encyclopaedia, Vol 18, para 692). Amenability to rectification had to be assessed as at

7 December 2014 (2012 Act, sch 4, para 17). The transitional provisions in the 2012 Act were

irrelevant to the operation of the Midas Touch. An inaccuracy had to be rectifiable in terms

of section 9. Trade Development Bank v Warriner and Mason (Scotland) 1980 SC 74 had been

concerned with the Sasines Register. The whole purpose of the Land Register was to avoid

searching antecedent conveyances for problems. If bad faith was not pled, the defenders

could not succeed.

Defenders

[27]

The essence of the dispute had been about the nature of the right disponed to the

first defenders in 1997, not the area of land affected by that right. It was not possible to

interpret the disposition as referring to the Deed of Conditions as conveying a servitude

right, but not a pro indiviso share in the ownership of the common parts.

[28]

A corporeal right could be conveyed in a parts and pertinents clause under reference

to a Deed of Conditions (Auld v Hay (1880) 7 R 663, at 668-9 and 673). That was

unremarkable (Reid & Gretton, Conveyancing: what happened in 2020?). Unlike PMP Plus v

Keeper of the Registers of Scotland (paras [52], [54] and [63]) and Miller Homes v Keeper of the

15

Registers of Scotland, all versions of the relevant plans clearly delineated the York Street ramp

and its associated turning circle. PMP Plus was compatible with this, in so far as it required

a purposive construction of the disposition (paras [70]-[72], citing Candleberry v West End

Homeowners Association 2006 SC 638, para [19]). The drawings to be agreed related only to

the podium. Even then, the parties recognised a possible need for a deed of variation. There

was no difficulty in construing the Deed in a manner consistent with an intention to make a

specific common conveyance. There had been no issue in terms of voidability on grounds of

uncertainty before the commercial judge.

[29]

The Midas Touch ended on 8 December 2014. The transitional provisions asked

simply whether the circumstances were appropriate for rectification. Good or bad faith was

not relevant. The only question was whether the pursuers were prejudiced as a proprietor

in possession. The defenders averred in clear terms that they were not. This gave rise to

inaccuracy. It was accepted that the defenders required to go to proof to rebut the

presumption of the pursuers' possession. The first defenders had, in any event, reacquired

pro indiviso ownership rights through their own prescriptive possession.

[30]

If bad faith were required, the commercial judge was correct to hold that it existed.

When the pursuers took title, the ramp and turning circle had been built. At that date,

looking at their own title, the pursuers would have recognised that the intention was for the

Phase II proprietors to acquire only common property. They could as a matter of general

property law only have done so as a result of Pardev's a non domino disposition. The terms

of the Deed would have directed a party in good faith to make inquiries of the first

defenders' title.

16

Decision

General

[31]

This is a dispute between commercial enterprises raised in the commercial court. It

is very important that the outcome of such a dispute is explained in terms which are kept

within reasonable bounds in terms of both length and comprehension. This is particularly

so where the judge's decision follows a hearing which has not involved any consideration of

testimony but was a legal debate on the import of conveyancing documents.

De praesenti

[32]

The starting point chronologically is the Deed of Conditions. This sets out, in clear

terms, the boundaries of the Phase I and II lands and defines with equal clarity what were to

be, and would become, the areas of ground on which two ramps, turning circles and related

structures serving the basement car park were to be constructed. These are defined as

common parts. In the event of the Deed of Conditions being incorporated into a disposition

to a purchaser, including the pursuers, the disposition would carry with it (upon

registration of title) a pro-indiviso right in common to the ramps or any other structure as

subsequently (or previously) constructed on the ground conveyed.

[33]

The pursuers belatedly raised the impact of the de praesenti principle. It was not

foreshadowed in the pleadings, the commercial judge's opinion, or even in the original

written note of argument before this court. The principle is that it is not competent to

convey an area of land which is ascertainable only by reference to an uncertain future event.

A conveyance operates de praesenti and the real right is acquired on registration (PMP Plus v

Keeper of the Registers of Scotland 2009 SLT (Lands Tr) 2 at para [56]). This principle,

according to the Tribunal in PMP Plus, followed from the terms of section 3(1) of the Land

17

Registration (Scotland) Act 1979, which vested a real right upon registration. There could be

no postponed vesting. A second principle, deriving from section 4(2)(a) was the

requirement for a sufficient description by reference to the Ordnance map.

[34]

There is no difficulty with the ascertainment of the boundaries of the land which was

to form the common parts, even although, at the time of both the Deed of Conditions and

the disposition to the first defenders, the ramps had not been constructed. The land is

clearly delineated in both the basement and ground floor plans attached to the Deed. Even

in the unlikely event of the ramps never being built, the area delineated in red on the ground

would have vested in the first defenders as common property with Pardev, as the then

owners of the Phase II land, once the first defenders' interest in the land, as contained in the

disposition to them, came to be registered. There is, in short, no uncertainty. The potential

for the precise nature of the structures to be changed is of no practical significance in this

case, given that there is no suggestion that they were varied in the manner provided for by

the Deed.

[35]

Had there been any difficulty in defining the extent of the interest in land to be

conveyed and registered, this ought to have been noticed by the Keeper. No problem was

perceived by her; and rightly so. It may nevertheless not be entirely without significance

that, by the time of the disposition to the pursuers, the York Street ramp was in existence

and the nature of its ownership was set out in the Deed to which the pursuers' title sheet,

and presumably the disposition of the Phase II land to them, referred.

[36]

If the de praesenti principle were to be applied in the manner sought by the pursuers,

it would operate as a substantial obstacle to developers of multi-occupation phased

development sites for which they wish to set out ab ante the rights and obligations of

potential purchasers in connection with what is intended to be used as common property (cf

18

Gretton & Reid: Conveyancing (5

th

ed) para 12.29 on inconvenience and excessive legality).

The use of the Deed of Conditions by Pardev was a common, sensible and appropriate use

of a single document setting out the conditions to be incorporated by reference in

subsequent split off dispositions. In practical terms, no doubt the nature of the structures to

be built would already have been the subject of extensive planning and building warrant

procedures. The nature and location of the structures was described in a manner which met

the de praesenti principle.

A conflict of title sheets?

[37]

The 1979 Act was not without its problems in terms of practical application. The

creation of a register of interests in land (1979 Act, s 1(1)), rather than a record of deeds of

conveyance, and the plotting of these interests on an Ordnance map (1979 Act, s 6(1)(a)), so

that a purchaser need look no further than the relative title sheet, was (and is) an ambitious

project. The registration of the interest creates the real right in a new owner, subject only to

those real burdens and other encumbrances which are listed on the title sheet (1979 Act,

s 3(1)). If one of the burdens or encumbrances, which existed in favour of another owner,

did not appear on the sheet, it would thereby be extinguished by the Keeper's Midas touch.

Therein lay a difficulty, if the interest as registered was "inaccurate"; hence the remedy of

rectification in that event (1979 Act, s 9(1)). Rectification was not to be permitted when it

"would prejudice a proprietor in possession" (1979 Act, s 9(3)).

[38]

The 1979 Act did not contain specific provisions for the registration of common

property. This could, in practical terms, be achieved in at least three different ways. First,

the whole of the proprietor's interests, exclusive and in common, could have been plotted on

the Ordnance map. This would mean that there could be several title sheets with ostensibly

19

conflicting maps (see Reid and Gretton: Land Registration at para 4.20); the resolution of

which would have to be by reference to words elsewhere in the title sheet. Alternatively,

only the exclusive area could be delineated on the map, with the common area being

referred to as a pertinent in the title sheet for the main area. This was a preferred method at

least prior to the 2012 Act (see eg Registration of Title Practice Book (2000) para 5.52). The

system under the 2012 Act is not supposed to permit either method. Rather, and this is the

third method, a shared area should form its own cadastral unit and have its own title sheet

(2012 Act, s 12(1) and (2)), although there is scope for the earlier method to continue in

operation (2012 Act, s 12(3)).

[39]

Against that background, one question which arose before the commercial judge was

whether there is a conflict between the two title sheets. The sheets certainly approach the

effect of the Deed of Conditions differently and, to that extent, they are inconsistently

drafted. The first defenders' title sheet contains Ordnance maps which have delineations

only of the ground exclusively owned. The description in the property section contains the

words "together with the rights specified in the Deed of... Conditions in... the Burdens

Section". The terms of that Deed are repeated, whereby the podium and the vehicular

access are to be "owned in common" by the Phase I and II proprietors. The podium and

vehicular access are delineated on Supplementary Plans 1 and 3, which are part of the title

sheet. On its face, the first defenders' title sheet creates a real right not only in the

exclusively owned area delineated in red on the Ordnance map but also in common in

respect of the common parts. The right conveyed was not one of servitude but one of

ownership. Quantum valeat, that conforms to the disposition to the first defenders which, for

the avoidance of doubt, conveyed those areas.

20

[40]

The pursuers' title sheet is in a different style or form. The description of the subjects

in the property section is remarkably short. It states simply that the subjects are edged in

red. It does not make any distinction between land held exclusively and that which is in

common. As has already been seen, the area edged in red includes not only the area to

which Pardev retained exclusive ownership, following the disposition to the first defenders,

but also to what were, in terms of the Deed, the common parts. Following the disposition,

Pardev had no title to convey exclusive ownership of the common parts to anyone since they

had ceased to have exclusive title to them (nemo dat quod non habet). The dispositions to the

pursuers and their successors in title have not been produced. It is not possible to probe

how matters might have developed. The pursuers simply found upon their title sheet as

establishing their exclusive ownership of the common parts. The question then is whether

that is its effect.

[41]

As described above, one way of plotting subjects, at least prior to the 2012 Act, was

to include not only an exclusively owned area but also any common parts within the

Ordnance (but not the cadastral) map. This would not be inaccurate, even although other

common owners would have title sheets delineating the same common area within the

totality. This ought not to pose a significant problem, as long as the matter is made clear

within the title sheet. In this case, the terms of the Deed of Conditions are included ad

longum in the Burdens Section. It may have been prudent to have included a reference to it

in the Subjects Section, but the import of the Deed is clear. In respect of the common parts, it

is not just a burden but pro indiviso ownership that is provided. A person who looked at the

title sheet would see that this was what is intended, since otherwise there would be little

point in including Supplementary Plans 1 and 3 which delineate the common parts.

21

[42]

Construed in this way, and differing from the commercial judge on this point, there

is no obvious conflict between the two title sheets. The pursuers' title sheet does not provide

for their exclusive ownership of the common parts. The first defenders' title sheet does

include the common parts. On this basis the commercial judge ought to have dismissed the

action against the first defenders as irrelevant. However, the first defenders did not cross-

appeal with a view to securing that remedy in advance of a proof before answer.

A non domino and bad faith

[43]

There is no question of there being an "a non domino" conveyance to the pursuers. If

there was a conveyance of exclusive ownership of the common parts, that is to say including

those which had already been conveyed by Pardev to the first defenders, it was in direct

conflict with the disposition to the first defenders. A domino already existed.

[44]

In the absence of averments, no issue of bad faith can arise. That is not to say that the

pursuers can be taken to have been unaware of the terms of the Deed of Conditions. Given

the terms of their title sheet, they clearly were aware of what the Deed said about the

common parts.

Inaccuracy and Proprietor in Possession

[45]

If there were a conflict between the title sheets, it is caused by an inaccuracy in one or

other of them which, leaving aside the question of a proprietor in possession for the

moment, could have been rectified under sub-section 9(1) of the 1979 Act. At the risk of

unnecessary repetition, once Pardev had conveyed a pro indiviso right in the common parts

to the first defenders, they ceased to have title to convey these parts exclusively to anyone

else, including the pursuers' predecessors in title. Exactly where the error (assuming there

to be one) in the pursuers' title sheet arose is unclear, but the existence of such an error is

22

manifest. The inaccuracy existed before the designated day. The first defenders are

therefore deemed to have the rights which they would have had in the event of rectification

(2012 Act, sch 4 para 17).

[46]

However, rectification would not have been possible under the 1979 Act if the

pursuers were proprietors in possession immediately before the designated day

(8 December 2014). Depending on which title is deemed to be inaccurate, the person

registered as the proprietor is presumed to be in possession unless the contrary is shown

(2012 Act Sch 4 para 18). The first defenders aver that they were in possession up until 2018,

when the pursuers began construction work on the Phase II land. Prior to that, the ramp(s)

had been used only for the carpark under their building. Since there is, at least on record, a

dispute on that factual matter, the case requires to proceed to a proof before answer.

Prescription

[47]

Linked to the issue of possession is prescription. The 2012 Act amended section 1(1)

of the Prescription and Limitation (Scotland) Act 1973 in a manner which allows

prescription to operate on land referred to in a title sheet. For reasons already explored, the

first defenders' title sheet and their disposition, in so far as relating to the common parts, are

at least habile to permit prescription to run in a manner which would create a real pro

indiviso right of ownership. If the first defenders possessed the ramp(s) for a period in

excess of ten years in terms of the 1973 Act, their title will be purified. Since this too remains

in dispute, the proof would also require to cover this area.

Outcome

[48]

The commercial judge's interlocutor of 29 May 2020 repelled the pursuers' second

and third pleas in law which sought respectively to exclude certain unspecified averments

23

from probation and decree de plano. The appropriate course of action, given that the

defenders do not seek dismissal of the action, is to leave all pleas standing and to allow a

proof before answer. The proof should be restricted to the two matters of fact which are in

dispute; the issues of proprietor in possession in terms of section 9(3) of the 1979 Act and the

operation of prescription under sub-section 1(1) of the 1973 Act. That is not to say that these

will be the only matters which may be the subject of submissions thereafter. At present, all

pleas, none of which refer to either possession or prescription, should remain standing. If

there is to be a determination based on either of these two points, it will be important that

appropriate pleas are inserted into the record.

24

FIRST DIVISION, INNER HOUSE, COURT OF SESSION

[2021] CSIH 44

CA46/19

Lord President

Lord Menzies

Lord Doherty

OPINION OF LORD MENZIES

in the Reclaiming Motion by

BAM TCP ATLANTIC SQUARE LIMITED

Pursuers and Reclaimers

against

(FIRST) BRITISH TELECOMMUNICATIONS PLC; AND (SECOND) FIRLEIGH LIMITED

Defenders and Respondents

_______________

Pursuers and Reclaimers: Dean of Faculty (Dunlop QC), Garrity; Morton Fraser LLP

First Defenders: Massaro; Shepherd & Wedderburn LLP

Second Defenders: Moynihan QC; Russel Aitken LLP (on behalf of Miller Samuel Hill Brown

LLP, Solicitors, Glasgow)

20 August 2021

[49]

I am grateful to your Lordship in the chair for setting out the background and

submissions in this reclaiming motion. I have not found it easy to reach a concluded view

on it. In particular, I was initially attracted by the submission for the pursuers and

reclaimers on the de praesenti principle, despite the fact that this was not raised in the

pleadings, nor was it argued before the commercial judge, nor did it feature in the Notes of

25

Argument. However, on reflection I have reached the view that this submission is not well

founded, and I agree with the reasoning of your Lordship in the chair at paragraphs [32]-

[36] above.

[50]

"[T]he principle of property law, not just "registration law", that real rights to land

can only operate de praesenti, renders ex facie invalid any conveyance of land ascertainable

only under reference to an uncertain future event, so that such a title cannot found

prescriptive possession" Miller Homes Ltd v Keeper of the Registers of Scotland, 2014 SLT

(Lands Tr) 79, at paragraph [30]. "...it is not possible to convey an area of land ascertainable

only under reference to an uncertain future event. A conveyance operates de praesenti and

the real right is acquired on registration" PMP Plus Ltd v Keeper of the Registers of Scotland,

2009 SLT (Lands Tr) 2, at para [56].

[51]

I accept both these statements of the law, but the circumstances of each of these cases

appear to me to be different from those in the present case. In PMP Plus the issue related to

a non-residential purchaser of an undeveloped area of ground within a residential

development site. The Keeper of the Registers of Scotland decided to register the title, but

only with exclusion of indemnity, because (1) the title sheets of the individual proprietors of

dwelling houses in the development appeared to grant a pro indiviso right to the common

parts, and the subjects could be said to fall within the description of such common parts, and

(2) in any event there was a significant risk that the title was voidable under reference to the

principle in Rodger (Builders) Ltd v Fawdry 1950 SC 483 where, properly understood, the deed

of conditions reflected a commitment to use the whole development subjects for dwelling

houses and common parts, and that the parts of the site left at the end unbuilt on by

dwellings would be owned in common by the house and flat owners by which the

developers were bound. The passage from paragraph [56] of the Tribunal's decision which

26

is quoted above must be read in the context of those circumstances, and bearing in mind that

the matter was the subject of agreement between the parties, so no contradictory

submissions were advanced.

[52]

The Tribunal accepted (para [70]) that they should seek to construe the deed of

conditions and the plan appended to it in such a way as to reflect a practical approach to the

registration of title and avoid holding that a title was ineffective from uncertainty. It

considered (particularly at paragraphs [61]-[65]) the desire for flexibility by the developer,

which will be a common feature, particularly on a big site. At paragraph [70] the Tribunal

accepted the appellant's contention that the intention was clearly that the common parts

were only to be defined at some future point after the start of the development. So, at the

time that the appellant's title was presented for registration, it was not possible to determine

from the deed of conditions and the plan appended to it whether the subjects to which the

appellant sought to register title was or was not in the common parts.

[53]

The circumstances in Miller Homes were strikingly similar to those in PMP Plus it

was impossible to ascertain the extent of the common parts of a residential development as

at the date of presentation of a title for registration, so it was argued that it was impossible to

ascertain if the appellant in that case had a good title, or whether it might found title on

prescriptive possession.

[54]

The circumstances of the present case appear to me to be different. In those cases the

boundaries and extent of the common parts could not be ascertained as at the date of

presentation of the title for registration. In the present case, as your Lordship in the chair

observes, there is no difficulty with the ascertainment of the boundaries of the land which

was to form the common parts. The desire for flexibility (common in cases such as this) to

which the Lands Tribunal referred in PMP Plus is apparent from the terminology of the deed

27

of conditions; it is clear that the works had not been carried out to form the common parts at

the time of the deed of conditions, and in looking to the future the deed of conditions

envisaged that there might be amendments or variations to the Approved Drawings, and to

the way in which the Podium and the Vehicular Access might be constructed but not

without the approval of each of the Phase I & Phase II Proprietors, each of which will act

reasonably (clause 2.3). The area occupied as, or allocated to, common parts is not affected

by this element of flexibility. I consider that this is sufficiently clearly identified, and is not

properly categorised as "an area of land ascertainable only under reference to an uncertain

future event". There were clearly uncertain future events anticipated, but unlike in the cases

of PMP Plus & Miller Homes, the extent of the land was not ascertainable only by these.

[55]

I agree with the observations of the Lands Tribunal in PMP Plus (at paragraph [70])

that it is appropriate to seek to construe the deed of conditions (and plans) in such a way as

to reflect a practical approach to the registration of title, and (where possible) to avoid

holding that a title is ineffective from uncertainty. The construction urged on this court (for

the first time) by the pursuers and reclaimers is not in accordance with these observations,

and in my view does not reflect a practical approach to the registration of title. I agree with

your Lordship in the chair on the de praesenti issue.

[56]

The point about whether or not there is a conflict between the title sheets of the

pursuers and the first defenders is an interesting one, and I find your Lordship in the chair's

reasoning on the point persuasive. However, the commercial judge held that there was a

conflict, and there is no appeal against her decision on this point, nor have we had the

benefit of argument on the point. I would prefer not to base my decision on this point.

28

[57]

I am in complete agreement with your Lordship in the chair's reasoning and

conclusions on bad faith, inaccuracy/proprietor in possession, and prescription, and need

add nothing further. I agree with your Lordship's proposed disposal.

29

FIRST DIVISION, INNER HOUSE, COURT OF SESSION

[2021] CSIH 44

C46/19

Lord President

Lord Menzies

Lord Doherty

OPINION OF LORD DOHERTY

in the Reclaiming Motion

by

BAM TCP ATLANTIC SQUARE LIMITED

Pursuers and Reclaimers

against

(FIRST) BRITISH TELECOMMUNICATIONS PLC; AND (SECOND) FIRLEIGH LIMITED

Defenders and Respondents

Pursuers and Reclaimers: Dean of Faculty (Dunlop QC), Garrity; Morton Fraser LLP

First Defenders: Massaro; Shepherd & Wedderburn LLP

Second Defenders: Moynihan QC; Russel Aitken LLP (on behalf of Miller Samuel Hill Brown

LLP, Solicitors, Glasgow)

20 August 2021

Introduction

[58]

I have reached a different conclusion from your Lordships, for the following reasons.

[59]

The defenders have two defences to the action. The primary defence is that on

registration of their disposition on 2 July 1997 the first defenders obtained a real right to a

one-half pro indiviso share in the Common Parts; that when the pursuers registered their

30

disposition in 2002 they obtained title as exclusive owners to the whole of the Common

Parts; that as a result immediately before the designated day (8 December 2014) there was an

inaccuracy in the register in respect of which the first defenders could have obtained

rectification in terms of s 9 of the Land Registration (Scotland) Act 1979; and that by virtue of

the operation of Sched 4, para 17 of the Land Registration etc. (Scotland) Act 2012 the first

defenders are now to be treated as if they had obtained that rectification. The secondary

defence is that if the first defenders did not obtain a real right to a one-half pro indiviso share

in the Common Parts on registration of their disposition, they nevertheless subsequently

acquired that right by reason of the operation of prescription.

[60]

In my opinion the primary defence falls at the first hurdle because on registration of

their disposition on 2 July 1997 the first defenders did not obtain a real right to a one-half pro

indiviso share in the Common Parts. However, in my view the secondary defence is suitable

for inquiry.

The first defenders' Title Sheet

[61]

The Property Section of the first defenders' Title Sheet contains the following

description:

"Description:

Subjects ALEXANDER BAIN HOUSE, 15 YORK STREET, GLASGOW G2 8LA

within the land edged red on the Title Plan, which subjects are shown edged red at

ground level on Supplementary Plan 4 to the Title Plan and edged red at basement

level on Supplementary Plan 5 to the Title Plan, together with the rights specified in

the Deed of Declaration of Conditions in Entry 3 of the Burdens Section."

The Title Plan contains the note "See Supplementary Plans". Supplementary Plans 4 and 5

are mentioned in the Property Section but Supplementary Plans 1, 2 and 3 are not.

31

Supplementary Plans 1, 2 and 3 are derived from the basement plan, the site plan and the

ground floor plan contained in the Schedule to the Deed of Conditions, and for all material

purposes they are identical to those plans.

The Deed of Conditions

[62]

The Deed of Conditions provides:

"1

Definitions

In this Deed (including the Recitals) the following words and expressions shall have

the meanings respectively given to them as follows:

`Approved Drawings' means such drawings as have been approved from time to

time by both the Phase I Proprietors and the Phase II Proprietors relative to the

Podium Works as the same may be amended or varied with the approval of both the

Phase I Proprietors and the Phase II Proprietors in accordance with this Deed;

...

`Common Parts' means the Podium and the Vehicular Access and will include all

common service media constructed or to be constructed thereon all as may be altered

or varied in accordance with this Deed from time to time and which will be owned in

common by the Phase I Proprietors and Phase II Proprietors subject to the terms of

this Deed;

...

`the Podium' means the raised platform to be constructed at ground floor level only

above the Vehicular Access as part of the Works and will include the pedestrian

accesses, (if these are to be constructed in accordance with this Deed), landscaping,

lighting, signage and any features (as part of the works or otherwise all to the extent

mutually agreed by the Proprietors) thereon and as indicatively shown hatched red

on the Ground Floor Plan and the final layout for which will be determined by the

Works carried out in accordance with this Deed and which will include where

appropriate any walls or structure exclusively serving the Podium and to a mutual

extent any walls or structure which are mutual between the Podium, the Phase I

Land on the one hand or the Phase II Land on the other.

...

`Vehicular Access' means those structures to be constructed pursuant to the Works

comprising (a) the vehicular ramps leading from York Street to basement level (`the

32

York Street Ramp') and the turning circle leading therefrom to serve the Phase I

Building and (by means of an access to be created as envisaged by Clause 3.2) to the

Phase II Buildings but excluding the area beneath the York Street Ramp which will

form part of the Phase II Land (as indicatively hatched black on the Basement Plan)

(b) the vehicular ramp leading from James Watt Street to basement level (`the James

Watt Street Ramp') but excluding the area beneath the same as indicatively cross

hatched black on the Basement Plan which will remain part of the Phase I Land) and

the turning circle leading therefore (sic) to serve the Phase I Building and (by the

accesses to be created leading from the turning circle and from the Hammerhead as

envisaged by Clauses 3.2 and 11.2) to the Phase II Buildings and (c) the structure,

sub-structure and means of support of and all load bearing walls and all surfaces of

and in relation to the York Street Ramp, the James Watt Street Ramp and the said

turning circles and the supporting structure of the Podium together with, to a mutual

extent, any walls which are mutual as between the Vehicular Access and Phase I

Land on the one hand or the Phase II Land on the other but excluding in each case

any area or property right at any level other than (1) at basement level (as aforesaid)

and (2) the ramps themselves and declaring that the final layout of the foregoing will

be determined by the Works carried out in accordance with this Deed, which

Vehicular Access is shown indicatively outlined in red but unhatched on the Ground

Floor Plan and the Basement Plan;

`Works' means the works to be carried out to form the Common Parts in accordance

with the Approved Drawings and this Deed.

2

The Works

2.1

Subject the Clause 2.2, as part of the works to construct the Phase I Building

(if the Phase I proprietor elects to construct the same) the Phase I Proprietor will

carry out or procure the carrying out of the Works in a good and workmanlike

manner in accordance with the Approved Drawings, all relevant statutory ...

consents and permissions and requirements ... which the Phase I Proprietor will

obtain and exhibit to the Phase II Proprietor and will complete the works within

12 months or such other period as the parties may agree after commencement and

for the foregoing purpose will be entitled to take access to the site of the Common

Parts.

2.2

If the Phase I Proprietor has not commenced the Works by 1 September 1997

then the Phase II Proprietor will be entitled to give notice to the Phase I Proprietor at

any time thereafter unless the Phase I Proprietor has then commenced the Works that

it intends to carry out the Works and the provisions of Clause 2.1 will apply mutatis

mutandis to the Phase II Proprietor ...; declaring the Proprietors will consult with

each other as regards the timing and party who is to carry out the Works.

2.3

The Approved Drawings shall not be amended or varied without the

approval of each of the Phase I Proprietor and the Phase II Proprietor each of whom

will act reasonably; Provided that on completion of the Works the Proprietors will

enter into a Minute of Variation of this Deed (and ensure that the same is registered

33

in the Land Register of Scotland) to record the final Approved Drawings and to

make any consequential amendments which may be required to this Deed to record

the physical position to that extent.

2.4

The Proprietor who carried out the Works will be entitled to reimbursement

of 50% of the cost reasonably and properly incurred and as approved by the other

Proprietor ... by it in designing and constructing the Works.

...

13

Common Property

13.1

The Common Parts will be owned in common by the Phase I Proprietor and

the Phase II Proprietor.

13.2

For the avoidance of doubt, subject to the terms of the Deed (a) the Phase I

Proprietor will be able to utilise, enjoy and deal with the Phase I Land (including any

part thereof falling beneath or above the Common Parts) at its discretion and (b) the

Phase II Proprietor will be able to utilise, enjoy and deal with the Phase II Land

(including any parts thereof falling beneath or above the Common Parts) at its

discretion.

..."

Discussion

[63]

In terms of the Deed of Conditions the Common Parts were to be the Podium and the

Vehicular Access. The Deed envisaged that they would be constructed at some time in the

future as part of the Phase I Building works (Clause 2.1, 2.2), in accordance with Approved

Drawings and all relevant statutory consents, permissions and requirements. It

contemplated a process after the disposal to the Phase I Proprietor in which the Phase I and

Phase II Proprietors would reach agreement as to the precise location and content of the

Works. On completion of the Works the proprietors were to enter into a Minute of Variation

of the Deed of Conditions to record any alterations to the Approved Drawings and to make

any consequential amendments required to record the physical position. The Minute was to

be recorded in the Land Register.

34

[64]

The disposition to the first defenders was granted on 30 April 1997 and they

registered their title on 2 July 1997. The construction of the Phase I Building, and of the

Common Parts, did not begin until later. It is not suggested that as at 2 July 1997 there were

any Approved Plans relating to the Works to the Common Parts, let alone that by that date

the final layout of the Works had been agreed.

[65]

In my opinion on a proper construction of the Deed of Conditions it does not provide

that the land on which the Common Parts would be constructed is to be common property.

Rather, it provides that the structures making up the Common Parts will be common

property.

[66]

In any case, in my view the Deed of Conditions did not definitively describe or

delineate the land on which the Common Parts were to be constructed. The descriptions of

the Vehicular Access and the Podium in Clause 1, and the indications in the basement and

ground floor plans of their proposed locations, did not provide definitive descriptions or

delineations of the land upon which each was to be erected. The Vehicular Access was

merely shown "indicatively outlined in red". The Podium was "indicatively shown hatched

red on the Ground Floor Plan". In each case it was provided that "the final layout will be

determined by the Works carried out in accordance with this Deed". In my opinion the land

was not sufficiently identified for there to have been an effective conveyance of a real right

to a one-half pro indiviso share of it to the first defenders when they registered their

disposition on 2 July 1997 (PMP Plus v Keeper of the Registers of Scotland 2009 SLT (Lands Tr)

2, paras [57] - [58]).

[67]

So far as the structures are concerned, they did not exist on 2 July 1997. That would

not have precluded an effective conveyance of them on that date if they had been clearly and

definitively described in the Deed of Conditions. However, they were not. All that was

35

done was to indicatively delineate their proposed locations on the basement and ground

floor plans. They were not sufficiently identified for there to have been an effective

conveyance of them to the first defenders on 2 July 1997 (PMP Plus Ltd v Keeper of the

Registers of Scotland, paras [56] - [58]).

[68]

Since registration of the first defenders' disposition on 2 July 1997 did not effect a

conveyance to the first defenders of a real right to a one-half pro indiviso share of the

Common Parts, or of a real right to a one-half pro indiviso share of the land upon which it

was proposed that the Common parts be located, the defenders' primary defence cannot

succeed. The averments relating to it are irrelevant.

[69]

The secondary defence is that the first defenders acquired a real right to a one-half

pro indiviso share of the Common Parts by the operation of positive prescription. In my

opinion the first defenders' disposition was a habile foundation writ for positive

prescription. I do not consider that it can be said from the terms of the disposition itself that

it is a self-destructive deed in so far as it purports to convey the right of common property.

At least in theory, the final layout of the Common Parts could have been agreed, or indeed

the Common Parts could have been built, by the date of registration of the disposition.

Reference would have to be made to extrinsic material to establish that that had not

occurred. See eg Cooper Scott v Gill Scott 1924 SC 309, Lord Justice-Clerk Alness at p 323;

Johnston, Prescription and Limitation (2

nd

ed) para 17.31; Reid and Gretton, Conveyancing 2014,

pp 137-139; cf. Miller Homes Ltd v Keeper of the Registers of Scotland 2014 SLT (Lands Tr) 79,

paras [35] - [41]. Since the pursuers deny that the first defenders have possessed the

Common Parts for the prescriptive period, the secondary defence will require to go to

inquiry.

36

[70]

I would have allowed the reclaiming motion by recalling the commercial judge's

interlocutor of 29 May 2020; by sustaining the pursuers' second plea-in-law to the relevancy

of the defenders' averments quoad the primary defence, and otherwise leaving all pleas

standing; and by allowing a proof before answer on prescription.

BAILII:

Copyright Policy |

Disclaimers |

Privacy Policy |

Feedback |

Donate to BAILII

URL: http://www.bailii.org/scot/cases/ScotCS/2021/2021_CSIH_44.html