Table of Contents

Introduction. 2

Background Facts 3

Group Structure. 3

Turnkey Development 5

Construction of Priors House. 7

Fitting out of Priors House. 9

The Evidence. 15

Issues in this Appeal 18

The Legislation. 20

Output tax liability. 20

Input tax credit 21

Operation of the Builder’s Block. 23

Were items of FF&E incorporated into Priors House?. 23

Were items of FF&E “building materials”?. 31

Was the FF&E an element of a single supply by PropCo to OpCo?. 37

PropCo’s Submissions. 41

HMRC’s submissions. 44

Discussion. 47

Conclusions. 52

Right to apply for permission to appeal 52

Annex One - Key Contractual Provisions. 54

Framework Agreement dated 10 September 2010. 54

Technical Services Agreement dated 10 September 2010. 57

Agreement for Lease and Development of Care Home Development Site at Old Milverton Lane, Leamington Spa, Warwickshire dated 21 March 2013. 57

Occupational Lease of Care Home at Old Milverton Lane, Leamington Spa, Warwickshire dated 11 August 2014 63

Agreement for the provision of consultancy services in relation to a development at Quarry Farm, Old Milverton Lane, Leamington Spa dated 5 April 2013. 67

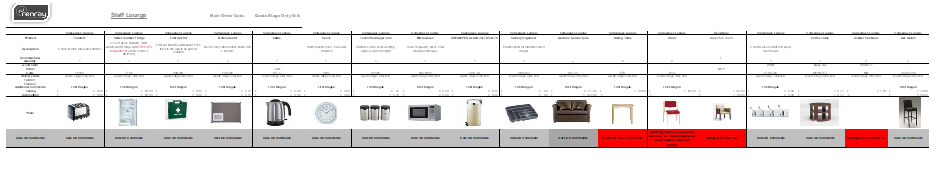

Annex Two –FF&E items whose “incorporated” status is in dispute. 72

Annex Three - Extract from Renray Specification. 89

DECISION

Introduction

1. The Appellant (“PropCo”) appeals against HMRC’s statutory review decision notified by letter dated 27 January 2017 upholding a VAT assessment for the 05/14 period dated 12 May 2016. The 12 May 2016 assessment was later replaced by a revised Notice of Assessment dated 21 May 2017. The VAT in dispute in this appeal is £96,291. This appeal is being treated as a lead case for another appeal by one of PropCo’s sister companies.

2. The appeal concerns the correct VAT treatment of certain items of furniture, fixtures, and equipment (“FF&E”) supplied with a new care home known as Priors House, Old Milverton Lane, Blackdown, Leamington Spa, Warwickshire, CV32 6RW (“Priors House”). Priors House was leased by PropCo to Care UK Community Partnerships Ltd (“OpCo”). The issues before the Tribunal are

(1) The extent to which the FF&E are “incorporated” into Priors House for the purposes of the “builder’s block”;

(2) Whether “incorporated” FF&E were “building materials” (or whether such items were excluded from being building materials). Credit for input tax on incorporated FF&E is blocked unless those items of FF&E are “building materials”; and

(3) Whether the FF&E formed an element of a single (composite) zero-rated supply of Priors House to OpCo.

3. At the video hearing of this appeal, PropCo was represented by Philip Simpson QC and HMRC were represented by Andrew Macnab.

4. Witness statements were produced from Matthew Rosenberg and Craig Prior for PropCo, and Keith Metcalfe for HMRC, and each of these witnesses gave oral evidence and was subject to cross-examination.

5. Matthew Rosenberg is currently the chief financial officer of Care UK Limited (“CUK”), the parent company of OpCo. He is also a director of PropCo and Silver Sea Property Holdings Sàrl (“SSPH” - the parent company of PropCo) and of OpCo. His employment with CUK commenced on 6 May 2014, and he became a director of OpCo, SSPH, and PropCo shortly thereafter. Mr Rosenberg was one of only two individuals that were directors of companies within both the SSPH and CUK groups (but currently he is the only one). Prior to joining CUK, he was the CFO of a European hotels business. He is a chartered accountant.

6. Craig Prior has been the Operational Projects Director of OpCo since August 2013. He is qualified to operate a residential care home in a regulatory compliant manner. His responsibilities include overseeing the development, construction and fit-out of all new care homes that are leased to OpCo and ensuring that the homes and their managers are compliant with all relevant regulatory requirements. Although his job title describes him as a “director”, he is not a director for the purposes of the Companies Act. In addition to his employment by OpCo, Mr Prior also works for CUK. However, he does not work for SSPH, Silver Sea Developments Sàrl (“SSD”) or PropCo.

7. Prior to his employment with OpCo, Mr Prior had been employed as an operations director and as a regional operations manager for other care home groups. In these roles he was responsible for the operational management and control of between 12 and 21 care homes. He also has previous experience as the manager of a 138-bed facility caring for individuals with dementia and other dependencies.

8. Keith Metcalfe is the HMRC officer responsible for the VAT assessments in this case.

9. In addition to witness evidence, an electronic bundle of documentary evidence comprising 1953 pages was produced in evidence.

Background Facts

10. For the most part, the background facts are not in dispute, and we find them to be as follows.

Group Structure

11. In 2010, funds managed by Bridgepoint (a private equity fund manager) incorporated Care UK Health and Social Care Holdings Limited (“Holdings”). Holdings (through subsidiaries) acquired the share capital of CUK (then called Care UK plc). Following the acquisition, the Bridgepoint funds and CUK’s management team set up a care home development business outside the Holdings group. The parent company of the group of companies forming the development business is SSPH, a Luxembourg company. Within the SSPH corporate group, various subsidiary companies (“SPVs”) are incorporated to buy and develop suitable sites into new residential care homes. Once completed, the new care homes are leased to OpCo, a subsidiary of CUK, which is the care home operating entity within the Holdings group. Another subsidiary of SSPH, SSD, a Luxembourg company, was incorporated to act as the project manager for the development of new care homes and is registered for UK VAT.

12. Neither PropCo nor SSD have any employees. Their directors (other than Mr Rosenberg, and previously another CUK director) are provided by a Luxembourg corporate services business. SSD outsources its obligations under the Framework Agreement to OpCo.

13. PropCo is a subsidiary of SSPH. PropCo is the SPV incorporated specifically in relation to the site acquisition, construction, and leasing of Priors House. PropCo was registered for VAT on 1 October 2010 as a non-established taxable person.

14. On 31 July 2019, a subsidiary of Holdings acquired the shares in SSPH, so that SSPH, PropCo, SSD, CUK and OpCo are now all indirect subsidiaries of Holdings.

15. The relationships between the entities in the SSPH and Holdings groups were at all material times governed by a number of agreements. The agreements relevant to this appeal are the Framework Agreement dated 10 September 2010 (“the Framework Agreement”), the Technical Services Agreement dated 10 September 2010 (“the Technical Services Agreement”), the Agreement for Lease and Development dated 21 March 2013 (“the Agreement for Lease”), and the Occupational Lease dated 11 August 2014 (“the Lease”). A selection of key provisions from each of these documents is set out in Annex One to this Decision.

16. Mr Rosenberg’s evidence was that he was not aware of any other agreements that related to the supply of the FF&E by PropCo to OpCo, and that as regards the FF&E, PropCo was “not giving anything away for free”.

Framework Agreement

17. The Framework Agreement is between SSPH, OpCo, SSD, and CUK. It sets out the overarching framework by which companies in the SSPH group are commissioned to appraise, plan, and execute the development of new care homes, and to arrange for such care homes to be leased to OpCo. The agreement also includes provisions dealing with sites developed by third parties which are leased to OpCo.

18. The Framework Agreement provides for a staged process. Scheduled to the Framework Agreement are various model forms of agreement that are to be used in relation to the development of a care home. These include (i) a schedule of amendments to the standard JCT Design and Build Contract, (ii) a model form of agreement for lease and development in respect of a care home, and (iii) a model form occupational lease of a care home.

19. The stages prescribed by Clause 7 of the Framework Agreement are broadly as follows:

(1) SSD investigates and pursues potential opportunities for the acquisition of sites and the development of care homes. Following the identification of a potential site, SSD prepares an Initial Feasibility Appraisal.

(2) If the Initial Feasibility Appraisal is positive, then SSD seeks an “exclusivity agreement” with the site owner and is authorised to engage a professional team to undertake further “due diligence” on the site and prepare draft drawings and specifications. The Framework Agreement sets out a budget for this work and the criteria and minimum requirements for the drawings and specifications. OpCo must prepare a draft business plan, in practice this is for a period of five years starting with the opening of the care home. Mr Rosenberg's evidence was that a five-year plan allowed for the care home to reach maturity with a stable occupancy of 92% to 93%; taking the business plan beyond five years had little value, as it became a desktop exercise in adjusting the component financial figures for inflation.

(3) SSD then prepares and sends a Final Transactional Appraisal to the boards of SSPH and OpCo for their review and approval. The Final Transactional Appraisal includes (amongst other things):

(a) Final draft drawings and specifications which accord with the design criteria and minimum requirements scheduled to the Framework Agreement.

(b) A business plan (incorporating an operating budget including details of projected EBITDAR - being earnings before interest, tax, depreciation, amortisation, and rent). Mr Rosenberg described the finances of OpCo and PropCo as being linked, as OpCo had to have a profitable care home in order to be able to pay rent to PropCo;

(c) A draft development budget;

(d) Drafts of relevant agreements; and

(e) The calculation of the initial rent payable by OpCo, which is to be calculated by reference to a rent cover of 1.6 to 1.8 times EBITDAR (or such other calculation as the parties may agree) (the reason this level of rent cover was chosen was because it corresponded to the financial covenants in the loan facility. Mr Rosenberg confirmed that the calculation of the initial rent for Priors House followed this formula);

(4) Following the approval of the Final Transactional Appraisal by the boards of SSPH and OpCo, an SPV is incorporated and buys the site, and the relevant agreements are prepared by SSPH and executed by the relevant parties. These agreements include the agreement for lease and development (in the form scheduled to the Framework Agreement, amended only with changes necessary to reflect the details of the particular development project) and the project documents (including the JCT Design and Build Contract and the agreements with the professional team).

(5) The development then goes ahead in accordance with the terms of the agreement for lease and development, the building contract, and the other agreements and documents.

(6) Following practical completion of the care home, OpCo and PropCo enter into a 25-year occupational lease of the care home in the form scheduled to the agreement for lease and development (which itself follows the form scheduled to the Framework Agreement amended only with changes necessary to reflect the details of the particular development project).

Technical Services Agreement

20. SSD has no employees. It therefore outsources its obligations under the Framework Agreement to OpCo pursuant to the Technical Services Agreement.

Turnkey Development

21. The developments undertaken by the SSPH group for OpCo are described by Mr Rosenberg as “turnkey developments” - in other words, that the properties developed by the SSPH group are supplied to OpCo in a state that means that they are capable of being immediately operated - all OpCo has to do is “turn the key” and walk in. Mr Prior described a “turnkey development” as a development where OpCo was able to turn the key and admit residents from the moment it acquired control of the building. He said that it was quite common in the care home sector for new care homes to be constructed on a turnkey basis; two of his former employers (Gracewell and Four Seasons) used turnkey developments.

22. Mr Rosenberg’s evidence was that Priors House was developed as a Turnkey Site under the terms of the Framework Agreement, with SSPH as the developer, and PropCo as the SPV company which acquired Priors House on completion of the development.

23. Mr Rosenberg’s evidence was that the care home is constructed and leased to OpCo inclusive of all of the FF&E required in order for the care home to be immediately operational. This is done under a single agreement and for the payment of a single, all inclusive, rent. Mr Prior described the arrangements as meaning that OpCo was only responsible for supplying “consumables” (such as food and drink, paper, and chemicals) and staff in order for the care home to be ready to accept residents. As we discuss below, in our view, and we find that, the reality of these arrangements is somewhat different.

24. In his evidence, Mr Rosenberg describes a number of the aspects of turnkey developments that make them attractive for both the landlord/developer and tenant. These include:

(1) Convenience - the tenant has a completed home ready for use.

(2) The developer has a tenant in place to whom the property is let once the construction has been completed. This reduces the risk to the developer of the property not being profitable or marketable.

(3) The development project is forward funded by the developer, which means that the tenant does not incur any costs until the project has been completed.

(4) These arrangements separate the operation of the business from the asset and allocate risks between developer and tenant in a manner that is apparently more attractive to their respective investors.

25. Virtually all of these advantages are present in any typical pre-letting arrangement between arm’s length parties, rather than solely in relation to a “turnkey” development. The only one that is not is “convenience”. But in the case of Priors House, any convenience is illusory, as all the obligations of the developer have been delegated to OpCo under the Technical Services Agreement, so OpCo (the tenant) has the responsibility for getting the property ready in any event.

26. And it strikes us that the other “advantages” may be considered illusory in cases where the ultimate shareholders in the developer and tenant are identical (as was the case in respect of PropCo and OpCo until 31 July 2019), or are members of the same corporate group (as has been the case in respect of PropCo and OpCo since 1 August 2019). Whilst these advantages may be apparent at the level of OpCo and individual SPVs - they disappear when considered from the perspective of the ultimate parent company or an investing shareholder. Indeed, Mr Rosenberg in his evidence described the finances of OpCo and PropCo as being linked, as OpCo had to have a profitable care home in order to be able to pay rent to PropCo.

27. Mr Prior describes another advantage of a turnkey development as being an additional warranty provided in respect of FF&E by the developer. He says the following in his witness statement:

50. Whilst [OpCo] could procure the FF&E directly from relevant supplier, entering into an agreement with [PropCo] for the development of the site on a turnkey basis provides [OpCo] with an additional warranty which is underwritten by the developer. The warranty from the developer is typically for 10 years in duration and is therefore approximately 9 years longer than the warranty [OpCo] would otherwise be offered by the FF&E supplier directly. Additionally the developer is a known entity, which means [OpCo] is better able to assess the developer’s financial capacity to meet and follow-through on the warranty if so needed. Therefore, where the purchase of the FF&E is funded by [PropCo] under the agreement to develop the site on a turnkey basis, the risk to [OpCo] (both financial and reputational) which may potentially arise in relation to defective goods is greatly reduced.

Mr Prior was cross-examined on this statement, and his initial response was that he was “unsure” about whether PropCo gave a 10-year warranty on all FF&E, and that any 10-year warranty was “more to do with building”. He was not able to refer to any provision in any agreement to support this statement and said that it was his “understanding”. Mr Macnab asked him whether a 10-year warranty applied to J-Cloths (one of the items that PropCo asserts is leased to OpCo under the terms of the Lease), to which Mr Prior said that these would have to be replaced, as would anything else that has a life of less than 10 years.

28. We consider the more plausible reason for the use of opco/propco structures is Mr Rosenberg’s evidence that a special purpose property vehicle appears to be able to negotiate better terms with lenders than an operating company. His evidence was that the growth of Holdings was constrained by cash-flow, and the opco/propco split provided good leverage and improved the profitability of the business. And his evidence in this respect accords with the experience of the Tribunal panel (as an expert tribunal familiar with opco/propco type structures generally). It therefore made commercial sense for Bridgepoint and Holdings to establish an opco/propco split so that the Holdings/SSPH businesses could access more favourable borrowing terms.

29. And as the SSPH companies would have access to more favourable borrowing terms, it also made sense for the FF&E (so far as possible) to be acquired by the SPV (financed by borrowings through the property development side of the structure), rather by OpCo.

30. Mr Rosenberg was asked whether these arrangements effectively allowed OpCo to acquire the FF&E on credit, and whether leasing was a method of funding the costs that OpCo incurs in running its business. Mr Rosenberg’s response was that in these arrangements the developer (PropCo) incurs the costs to acquire the asset, and OpCo is willing to pay rent to PropCo for the right to use the asset.

31. Mr Macnab asked Mr Rosenberg whether these arrangements meant that OpCo was able to obtain the use of the FF&E without incurring VAT (Mr Macnab said that HMRC did not regard any reduction in OpCo’s VAT liability as being abusive). Mr Rosenberg’s response was that OpCo was partially exempt and could not recover all of the input VAT it incurred.

Construction of Priors House

32. The proposals to develop Priors House go back to 2012 - which is prior to the involvement of either Mr Rosenberg or Mr Prior with SSPH, Holdings, OpCo and PropCo.

33. Mr Rosenberg was asked about his involvement with the development of Priors House (and the FF&E in particular), and his response was he was not involved with it, as he arrived at around the same time as Priors House opened. In any event, he would not be involved at the level of detail of FF&E, and questions relating to FF&E were better directed to Mr Prior.

34. Mr Prior’s evidence was that his involvement related solely to the fit-out of Priors House and its compliance with CQC requirements. He was not involved in the decision-making process to construct a new care home in Leamington Spa, nor in any of the contractual arrangements. Indeed, Mr Prior only became an employee of OpCo after the Agreement for Lease for Priors House was executed - so he was not involved in the initial design of the Priors House building as specified in the Agreement for Lease and the plans attached to it.

35. PropCo was incorporated in 2012, shortly before its acquisition of the site on which Priors Home was constructed.

36. On 17 July 2012, AECOM Professional Services LLP (under its previous name of Davis Langdon LLP) (“AECOM”) wrote to CUK with a fee proposal for the provision of professional services (including acting as employer’s agent and quantity surveyor, as quality monitor, and as CDM co-ordinator under a JCT Design & Build form of contract) in connection with the construction of Priors House. On 5 April 2013, SSD and AECOM entered into an agreement for the provision of consultancy services in relation to the development of Priors House. Included in Annex One to this decision are key provisions of that agreement, including Schedule 5, which sets out the services to be provided by AECOM (and which correspond to the services set out in their July 2012 proposal).

37. Mr Rosenberg described AECOM as construction and building specialists, and that it made commercial sense for SSPH and its subsidiaries to engage a company such as AECOM to manage the construction of Priors House. In his witness statement he said:

65. AECOM were engaged by [PropCo] to project manage the entirety of the development of the build from the planning processes through to the FF&E fit-out and ensured that the build was completed in accordance with the design and contract specifications agreed between [PropCo] and [OpCo]. This included overseeing the fit-out of the FF&E items and ensuring that the FF&E were sourced in a manner which was compliant with regulatory standards and from reputable suppliers. As a result, AECOM will ensure that the development is completed in accordance with the agreed timelines and specifications and will also resolve any disputes between the developer and the construction team.

38. Mr Rosenberg then went on to say that AECOM took instructions solely from PropCo and were “fully and only accountable to” PropCo.

39. In his witness statement Mr Rosenberg described the relationship between AECOM, PropCo, and OpCo as follows:

66. In order to help [PropCo] to ensure that the final development met the relevant operational requirements, members of [OpCo]’s team, who have significant experience of how a care home operates in practice, were ordinarily on site during the development and FF&E fitout processes i.e. from the start to end of the build.

67. [OpCo] were therefore readily available to advise [PropCo] on matters such as the plumbing of the sinks, the siting of electrical sockets and the likely movement of the residents around the home. This is logical and beneficial to both parties, as the [OpCo] team were going to ultimately operate the care home once the development was complete and therefore, had greater insight into how such items would be used in practice.

68. In order to streamline this process, AECOM, on [PropCo]’s behalf, therefore worked closely with [OpCo] to ensure that both the development and the installation of the FF&E were consistent with the likely end operation of the site as a profitable and working care home and all relevant legislation and regulation.

69. Nevertheless, the ultimate financial and contractual responsibility for the development and the FF&E fit-out vested in [PropCo] throughout.

70. The fit-out of the loose FF&E is ordinarily completed shortly after practical completion for reasons of practicality: the loose FF&E cannot be installed until after practical completion, as items such as bedroom furniture cannot be installed until after the walls have been erected and painted. Additionally, the practical completion certificate confirmation that the structural works are completed and structurally sound.

[…]

90. [PropCo] was both the owner and developer in the Leamington Spa build and as a result, [PropCo] was responsible both for securing the land and all subsequent development processes, including the design, construction, and completion of the build. Again, I had ultimate responsibility for both the procurement and development of the site.

[…]

94. Under the contractual agreements, [PropCo]’s responsibilities extended to undertaking the fitout of the FF&E items. This included ensuring that the FF&E were procured from reputable suppliers and installed in a manner which was compliant with all regulatory and legislative requirements.

95. Considerations regarding the scope, design and installation of the FF&E therefore took place during the early planning stages of the development, as part of the agreement as to the overall design and use of the completed premises. This was in part in order to ensure compliance with the Care Legislation and in part because certain items, such as built-in cabinets or the plumbing for items such as sluice machines, are required to be incorporated into the build.

96. As a result, [PropCo] made a commitment to incur the FF&E costs prior to the prospective tenant, [OpCo], taking on responsibility for the lease or becoming financially responsible for the completed development.

97. Nevertheless, as [OpCo] would ultimately be occupying and operating the care home, it was sensible to include [OpCo]in the discussions as to the placement of the FF&E. In so doing, [PropCo] was able to ensure that the care home, once completed, was capable of operating effectively and that the requirements of Regulation 15 were met.

98. As indicated above, I am a director of both SSPH and [OpCo]. From [OpCo]’s perspective, it would have been inconvenient, time consuming and costly if following practical completion they then had to also separately source and install the FF&E items. Where the developer has the end-to-end engagement, it is for the developer to ensure that the completed site is fit for purpose and therefore that all connections are appropriately sited. This includes matters such as ensuring that the walls are appropriated spaced, the storage capacity is adequate and the completed care home is equipped with the FF&E necessary for the care home to be operational. The tenant can merely walk into the completed building and open the premises for trade, untroubled by matters such as contractor or sub-contractor disputes, overruns and budget management. The tenant is therefore able to save the immediate capital spend on FF&E which would otherwise cause the opening of new homes to be very burdensome for the tenant.

40. Mr Prior described AECOM as acting as a “middle person”. He was asked whether AECOM were on “your” side by Mr Macnab, to which Mr Prior’s response was that they were “on both sides” and were “independent” as OpCo employed their own project managers. But Mr Prior also said that he was not involved in the negotiation or agreement of any of the contracts relating to the development of care homes and was not involved with the engagement of AECOM or the engagement of Thomas Vale Construction plc - these were all matters for Mr Rosenberg.

41. On 21 March 2013, PropCo (as Landlord) entered into an Agreement for Lease and Development (“the Agreement for Lease”) with OpCo (as Tenant). SSD (as Developer) and CUK (as Guarantor of OpCo) were also parties. We note that the Agreement for Lease was executed before Mr Prior began his employment with OpCo.

42. Although a copy of the Building Contract was not included in the bundle, we infer from the terms of the Agreement for Lease that Thomas Vale Construction plc was engaged by SSD (not PropCo) as contractor under a JCT Design and Build Agreement dated 23 May 2014. As an expert tribunal used to dealing with property development, we have some familiarity with the suite of JCT building contracts, and a broad understanding of the way in which JCT Design and Build Agreements function.

43. In order for the grant of a major interest in Priors House to qualify for zero rating, a “Certificate for sales and long leases of zero-rated buildings” must be completed in the form specified in Section 18 of VAT Public Notice 708 (Buildings and Construction). The certificate for Priors House was dated 13 May 2013 and delivered by OpCo to PropCo. It states that the “Value (or estimated value) of the supply” [of the care home] was £199,500.

44. Notice of Practical Completion was given to Thomas Vale Construction plc by AECOM (as Employer’s Agent) on 23 May 2014. The Notice was given subject to the agreement of the contractor to complete outstanding works set out in a covering letter from AECOM dated 23 May 2014. This included various snagging and other items, most of which had to be resolved by 6 June 2014.

45. The Lease between PropCo (as landlord), OpCo (as tenant) and CUK (as guarantor), was executed on 11 August 2014. The term of the Lease is 25 years from and including 24 May 2014.

Fitting out of Priors House

46. A care home has to be registered with the Care Quality Commission (“CQC”) and comply with their standards, which include health and safety, infection control, and the safeguarding of vulnerable residents. CQC’s requirements need to be considered in the design of the care home (including the choice and location of FF&E).

47. CQC’s requirements depend upon the circumstances of the residents of a care home and the services it offers. Mr Prior gave as an example, a care home (such as Priors House) which catered for residents with dementia. Such residents have greater dependencies and requirements than other residents, which need to be reflected in the design of the home and the furniture and other equipment used.

48. Mr Prior provided detailed evidence of the requirements of CQC. His evidence was that all the FF&E supplied by PropCo to OpCo was required by OpCo for it to operate Priors House as a care home in compliance with CQC’s requirements (and other relevant regulatory obligations).

49. Of the various requirements prescribed by CQC, of particular relevance to this appeal are the requirements relating to the physical attachment of furniture and other items to walls and floors. Mr Prior describes this in his witness statement as follows:

39. […] [OpCo]’s health and safety requirements provide that items which are over 1 metre in height such as wardrobes or bookcases, which would ordinarily be “loose” items in a domestic setting, are required to be attached to the wall. This is consistent with the CQC’s guidance on the application of Regulation 12 of the Health and Social Care Act 2008 (Regulated Activities) Regulations 2014 (the “Regulations”) as considered in the CQC’s Inspection Reports for each care home and best practice. Similarly, televisions are required to be installed on brackets and the brackets must be attached to the wall. These are attached to the wall by way of a screw and therefore, it is possible to detach these items from the wall without causing damage to the building.

40. These attachment measures are aimed at reducing the risk of vulnerable occupants causing harm to themselves or others by pulling over potentially large and heavy furniture.

41. Residents with physical dependencies often use fixtures and furniture to provide additional support and stability when moving around the premises, which means it is imperative that items such as mirrors are more securely attached to the wall. This is because there is risk of greater harm to the resident if such item is accidentally pulled from the wall or removed in an unsafe manner. This risk is increased where the care home provides dementia care and accommodation, as residents with these specific dependencies often have a decreased awareness of the stability of these items or the harm which may occur if the items are improperly used. Securing these items helps to maintain the residents’ independence and provide reassurance to family members and carers. Nevertheless, it is still possible to remove these items and move them to other rooms in the home without causing damage to the building.

50. Mr Prior also described the design philosophy adopted by OpCo:

24. The key principles in the design and building of a care home are to create a homely, domestic environment in which residents can live with dignity and find care, security, support, privacy and companionship. It is therefore important that the home does not feel impersonal, institutional or clinical.

[…]

51. CUCP care homes, including Leamington Spa, are designed to be a “home for life”, meaning that CUCP focuses on ensuring that the residents are happy, settled and as far as possible, able to continue to lead independent lives.

52. Incumbent in that commitment is the requirement, as regulated by the CQC, to offer the resident a choice in how they occupy and use the premises.

[…]

54. The residents’ choice primarily affects the individual’s bedrooms, however in a small number of cases this element of choice will extend to the communal areas. The most obvious example of how residents’ choice operates in practice is in the selection of the colour scheme of the residents’ room. CUCP ordinarily offer 8 different colour schemes for the residents to choose from and a certain number of rooms will be made available in each of those colour schemes. To the extent that, for example, a “green” room is not available at the time of the resident taking occupation of the care home, the resident may request that the colour scheme of an otherwise available room be changed to meet their personal preference. In addition to changing the soft furnishings, this will include removing and changing items such as the curtains. As a result, CUCP requires the ability to change and move the FF&E around the premises.

[…]

56. As recorded at pages 84 to 100 of the 2019 CQC Inspection Report, CUCP also in practice moves FF&E around the premises where the rooms are occupied by a couple. This is in order to facilitate the couple sharing one room for sleeping and using their other room as a shared living room.

57. As regards the communal rooms, the residents are often offered a choice as to how they would like to use the room and as a result, what items are FF&E are necessary to be installed in that room. By way of example, the residents may elect to turn a craft or hobby room into a cinema.

58. Again, CUCP therefore requires the ability to change items in, for example, the residents’ rooms and to move the FF&E items around the care home, dependent on both the residents’ personal choice and preferences and the residents’ and staff’ wellbeing requirements. CUCP require the ability to make such changes without damaging the structure of the care home.

51. Mr Rosenberg has limited involvement with the selection and installation of FF&E. He was not involved with FF&E in relation to Priors House, as he only joined the businesses in May 2014. And after he joined the businesses, he described his involvement with FF&E as being limited to the approval of payments to suppliers, and that questions relating to FF&E were better directed to Mr Prior. He described Renray Healthcare Limited (“Renray”) as one of the suppliers of FF&E used by the businesses, and he said that they assisted in the fitting-out of FF&E into care homes.

52. Mr Prior said that he would ordinarily become involved with the design of a care home to ensure that it met all regulatory requirements. He would review the build specifications and the FF&E to ensure that it met CQC’s requirements.

53. Mr Prior’s evidence was that choice and location of FF&E were matters which OpCo discussed with PropCo during the early planning stages of Priors House, to ensure that CQC’s requirements were “incorporated into the build”.

54. In his witness statement, Mr Prior said that ordinarily the OpCo projects team will be on the premises of a care home during the fit-out of the FF&E. This would be undertaken:

30. […] after the building has reached practical completion. The fit-out of the FF&E is usually done after practical completion, as the developers needed to first obtain a building certificate confirming that the development was structurally sound. This must be done before the FF&E fit-out can be commenced and residents accepted into the building. Once the care home has been fitted out, the care home staff will be brought on site for 3 weeks of training, following which the care home will be opened to residents. This inevitably leads to a small delay between practical completion and fit-out, however this delay is necessary for health and safety reasons, as it avoids a scenario where care home staff are on site for training whilst heavy furniture is being moved and installed around the premises.

55. The specification annexed to the Building Contract (“the Construction Specification”) requires the contractor to provide a carpenter to be available for two weeks following practical completion of the construction to assist with fit out.

56. There is a six-month lead time for sourcing and delivery of FF&E, so its selection and the timetable for its fit-out is finalised during the course of the construction of a care home. In the case of Priors House because of overruns and delays in its construction, there was an overlap between the finalisation of the construction (described in AECOM’s covering letter to the practical completion certificate) and the commencement of the fitting-out of the FF&E.

57. Once the fitting-out has been completed, the care home staff will be brought onto the site for three weeks of training. Only then will the care home be opened to residents.

58. The application to CQC for registration of a care home must be made at least 12 weeks prior to the planned opening date, and typically CQC will undertake a pre-occupational inspection prior to the planned opening date.

59. In the case of Priors House, the key dates in relation to its development were as follows:

|

|

Date |

|

Commencement of training for Priors Hall leadership team (OpCo) |

3 March 2014 |

|

Commencement of training for Priors Hall core care team (OpCo) |

8 May 2014 |

|

AECOM notice of practical completion |

23 May 2014 |

|

Commencement of Lease term |

24 May 2014 (but Lease executed on 11 August 2014) |

|

Application to CQC for registration |

26 May 2014 |

|

OpCo goes into occupation as licensee (first working day after practical completion) |

27 May 2014 |

|

Commencement of FF&E fit out |

27 May 2014 |

|

CQC pre-registration inspection |

28 May 2014 |

|

Completion of FF&E fit out |

6 June 2014 |

|

CQC registration |

23 June 2014 |

|

Arrival of first resident |

23 June 2014 |

|

Lease executed |

11 August 2014 (but Term commenced on 24 May 2014) |

|

First CQC compliance inspection |

28 June 2016 |

60. We note that 23 May 2014 was a Friday, and that Monday 26 May 2014 was a bank holiday. The first working day after practical completion was Tuesday 27 May 2014.

61. Mr Rosenberg’s evidence was that AECOM oversaw the fit-out of the FF&E items and were responsible for ensuring that the FF&E items were sourced in a manner which was compliant with regulatory standards and from reputable suppliers. However, Mr Prior’s evidence was that AECOM were not involved in the sourcing and installation of FF&E unless the item of FF&E needed to be integrated into the construction programme (such as a custom-built servery counter which was integrated into the building itself). They would not be involved in sourcing or installing items bought from third-party suppliers (such as an armchair). Rather there was an individual employed by OpCo who was responsible for sourcing FF&E.

62. The majority of the FF&E was supplied by Renray a company specialising in supplying care homes. Mr Prior’s evidence was that the choice of Renray as a supplier had been made by OpCo in conjunction with “the exec”. However, there are other items supplied by other companies. These range from specialist items of equipment (such as telecommunications and computer networking, televisions, coffee machines and photocopiers) to more unusual items such as jigsaws and books designed for individuals with dementia. The total cost incurred by PropCo for FF&E (inclusive of VAT) was £586,422.97.

63. Included within the hearing bundle is “Revision 5” of the “FF&E Specification Address: Leamington” (“the Renray Specification”). Mr Rosenberg’s evidence was that this was prepared by Renray in consultation with OpCo. Mr Prior’s evidence was that the first draft of this specification was prepared by OpCo as part of the procurement process with Renray. It was, he said, a list of everything required by OpCo to run Priors House as a care home (with the exception of consumables such as food, paper, and chemicals). No copies of any of the other communications between OpCo and Renray were included in the bundle, nor was a copy of Renray’s supply and installation contract.

64. The Renray Specification includes in its heading “Care UK Order No ARLS/AW600/GB01”. Mr Prior said that the reference in the heading to the specification should not have included “Care UK” but should have referred instead to PropCo. For the reasons given above, we do not find Mr Prior’s evidence reliable in this respect and find that the reference to “Care UK” (which we find must be a reference to OpCo) is correct as on any basis OpCo would be responsible for the sourcing of FF&E.

65. Mr Prior described the procurement process with Renray as involving a “design freeze meeting” attended by representatives from Renray and representatives from OpCo’s design team and OpCo’s regional director. A colour scheme for the home would be agreed with Renray, and a subsequent meeting would be convened at a later date to review “mood boards” presented by Renray. An initial specification for the home would then be prepared by OpCo and sent to Renray for pricing. The specification would be returned populated by prices and with a thumbnail illustration for each item incorporated into the specification. This iterative to-and-fro process would be repeated as the Renray Specification was finalised.

66. The Renray Specification goes through each room in Priors House and sets out in detail the items of furniture and equipment needed for that room. By way of example, the page of the Renray Specification for a staff lounge is set out in Annex Three to this decision. It can be seen that a dining table, stacking chairs, and scatter cushions had been removed from an earlier iteration of the specification, and that a tub chair had been added in the place of stacking chairs.

67. Once finalised, the Renray Specification was sent to “the exec” for final “sign-off”. Providing the price for the items specified fell within the budget for the care home (as set out in the Final Transactional Appraisal), Mr Prior said that it was likely to be approved. We asked Mr Prior what he meant by “the exec”, and he described this as meaning the senior management team within CUK.

68. Renray not only supplied the items included in their specification but fitted them as well. During the fitting out of Priors House, Renray would install the equipment they supplied. OpCo would also be on site to supervise the installation.

69. It can be seen from the table above that the installation of the FF&E commenced after practical completion of Priors House and after OpCo went into occupation. The installation was completed before the Operating Lease was granted.

70. Mr Prior was asked about the siting and location of furniture in rooms, and he said that the rooms in Priors House had been designed for the furniture to be located in a particular place. This was needed to ensure, for example, that the room was accessible for wheelchairs, with sufficient turning spaces. He was asked whether the furniture had been designed with these issues in mind, but his response was that the majority of the furniture had been designed so as to be suitable for use by a person with disabilities.

71. Mr Prior also explained that although OpCo did not as a rule normally move furniture, there were times when it was moved. He gave as an example the case of couples who would be allocated two bedrooms with intercommunicating doors. One room would be used as their bedroom with en-suite bathroom. The other room would be a living room, with the associated bathroom converted into a kitchenette. In consequence furniture would need to be moved and relocated between the rooms.

72. It was also the case that some residents wanted the bedroom to include some of their own furniture, and OpCo would accommodate this whenever possible and appropriate, in order to provide the resident with a homely environment and to comply with CQC’s requirements in this regard. Mr Prior said that OpCo kept one or two bedrooms in a care home unfurnished, and these would be available to a new resident who wanted to furnish his or her bedroom with his or her own furniture.

73. During the course of cross-examination of Mr Rosenberg and Mr Prior, we discovered that the distinction made between “consumables” (food, paper, chemicals) and the FF&E supplied for a “turnkey” development was blurred, as there were a number of items supplied to PropCo by Renray that had a very limited life or were disposable. The prime example of this were the “J-Cloths” which were included in the list of FF&E supplied by PropCo. There were also a number of single-use items included in the list, such as resuscitation masks and the contents of first-aid kits (such as wound dressings). Further, although we had no specific evidence on the point, our own personal experience is that items such as light bulbs, mop heads, plastic denture baths, and plastic protective googles have a limited life (and Mr Prior’s evidence was that first-aid kits expired after five years).

74. When Mr Rosenberg was questioned about these items, his response was that he didn’t think of these items as rented. but that these items were owned by the landlord and that the tenant had a leasehold interest in the item, and that the items had a “varying degree of life”. Asked what happened when a J-Cloth was no longer usable and was thrown away, Mr Rosenberg’s answer was the Lease was a “triple net” lease (what we would describe as a full repairing lease), and that the tenant was responsible for all repairs and replacements. If the item was included at the start of the lease, and the item was broken, the tenant would be expected to replace the item by the time the lease ended. Mr Rosenberg said that these items were included in the costs of the development incurred by PropCo, were provided by PropCo, and contributed to the rental return received by PropCo.

75. Mr Prior’s evidence was that J-Cloths were not “consumables”. He said that there would be a number of cleaning cupboards in a care home, and in each cupboard there was a trolly on which there were different coloured brushes and mops (for cleaning different kinds of spills and waste), and different coloured cloths which were associated with the different brushes and mops. As regards wound dressings, Mr Prior said that it was a consumable, as a plaster could only be used once.

76. Mr Prior stated that PropCo’s consent was not required to relocate or replace items of FF&E. Mr Prior’s evidence was that the care home’s annual operating budget would make provision for the repair and replacement of worn or soiled items (to the extent that the budget was insufficient, the care home manager would need to put a new budget to “the exec”). When asked about the provision of new items, Mr Prior’s evidence was that CQC did not make retrospective changes to equipment requirements. If the care home manager considered that additional equipment was desirable, the manager would make a recommendation to “the exec” for the equipment to be purchased at OpCo’s cost. As the new equipment was purchased by OpCo, it would not form part of the FF&E within the Lease and would remain the property of OpCo.

77. We noted also that some packs of tea and coffee were provided with the tea and coffee machines.

78. During the course of our questioning of Mr Prior, he stated that staff uniforms were not included in the list of items provided by PropCo. Mr Prior’s explanation was that there was no obligation under CQC regulations for staff to wear uniforms - as there were circumstances where the wearing of uniforms in a care setting would be inappropriate. The use of uniforms at Priors House was only the practice of CUK and OpCo, and therefore it was outside the scope of a “turnkey” development, as these were not needed by a care home operator to be able to operate a care home from day one.

The Evidence

79. Mr Rosenberg’s evidence was that:

(1) PropCo was both the owner and the developer of Priors House;

(2) the ultimate financial and contractual responsibility for the development and the FF&E fit-out vested in PropCo throughout;

(3) PropCo was responsible for the design, construction and completion of the build of Priors House;

(4) Priors House was developed as a turnkey development;

(5) He (Mr Rosenberg) had ultimate responsibility for the procurement and development of the Priors House site;

(6) AECOM took instructions solely from PropCo;

(7) AECOM were fully and only accountable to PropCo;

(8) AECOM oversaw the fit-out of the FF&E items and ensured that the FF&E items were sourced in a manner which was compliant with regulatory standards and from reputable suppliers;

(9) OpCo advised PropCo on aspects of the design of Priors House and the selection and sourcing of FF&E; and

(10) Under the contractual arrangements PropCo’s responsibilities included undertaking the fit out of FF&E.

80. Mr Prior’s evidence was that:

(1) Priors House was developed as a turnkey development;

(2) AECOM acted as a “middle person”, were “on both sides”, and were “independent” (as OpCo employed their own project managers);

(3) choice and location of FF&E were matters which OpCo discussed with PropCo during the early planning stages of Priors House, to ensure that CQC’s requirements were “incorporated into the build”;

(4) OpCo’s recommendations were sent to “the exec” for “sign off”, and that “the exec” then communicated with PropCo (although he had no knowledge as to how this was done);

(5) development on a turnkey basis provides OpCo with an additional 10-year warranty underwritten by the developer, which is longer than the warranty OpCo would otherwise be offered by the FF&E supplier directly; and

(6) it was quite common in the care home sector for new care homes to be constructed on a turnkey basis and that two of his former employers (Gracewell and Four Seasons) used turnkey developments.

81. Mr Rosenberg was neither a director nor an employee of any of OpCo, CUK, PropCo, SSPH, or SSD at any point of time during the planning and construction of Priors House. His evidence was that he was not involved in the purchase or procurement of the FF&E of any care home within the group - save to authorise spending after he joined the businesses. And he confirmed that as he joined the businesses at around the same time as Priors House opened, he was not, and could not, have been involved in the development or fitting out of Priors House.

82. Mr Prior’s evidence was that he was not involved in the decision-making process to construct a new care home in Leamington Spa, nor in any of the contractual arrangements. His involvement in the development of Priors House (prior to its opening to residents) related solely to the fit-out of Priors House with FF&E and its compliance with CQC requirements.

83. We find that to the extent that anyone other than OpCo had contractual responsibility for undertaking the fit-out of FF&E, it could not have been PropCo. Mr Rosenberg’s reference to the contractual arrangements can only be a reference to the Agreement for Lease and the Lease itself, as PropCo was not a party to any of the other agreements. Under the terms of the Framework Agreement and the Agreement for Lease, although PropCo was the owner of Priors House, it was SSD, and not PropCo, that was the developer of Priors House (it was SSD, not PropCo, that entered into the Building Contract with Thomas Vale Construction plc), and under the terms of the Agreement for Lease, whilst PropCo was liable for meeting the costs of the development of Priors House, it was SSD that had contractual responsibility for undertaking the development.

84. As Mr Rosenberg only joined the business at around the time that the construction of Priors House was completed, we do not understand his statement that he had ultimate responsibility for the procurement and development of the Priors House site.

85. Mr Rosenberg did not provide details of the source for his evidence about the communications between the various companies and that developments were undertaken on a “turnkey” basis, but in the course of cross-examination he said that there was a “template process” used by the businesses for all developments, and that all sites - both before and after he joined the businesses - followed the template. His evidence was that, so far as he was aware, nothing had changed since he joined CUK, and none of the documents have been amended. If this “template process” was merely the provisions of the Framework Agreement, then this “template” says nothing about new developments having to be undertaken on a “turnkey” basis. If the template is something more than just the Framework Agreement (and the model documents associated with it), copies were not included in the bundles, and there is no evidence (other than Mr Rosenberg’s second-hand oral evidence) that this “template process” had been used for Priors House, and Mr Rosenberg gave no source for his belief that it was so used.

86. Mr Rosenberg and Mr Prior both assert in their evidence that OpCo communicated with PropCo about various matters. Mr Rosenberg said that OpCo advised PropCo on issues such as the plumbing of sinks and the siting of sockets. Yet, if this occurred, it was before Mr Rosenberg joined the Holdings and SSPH companies, and it would be something of which he could have no first-hand knowledge.

87. Mr Prior’s evidence was that OpCo made recommendations to “the exec”, and it was the exec who communicated with PropCo - as to which he had no first-hand knowledge.

88. There was no documentary evidence of any communications between SSD/PropCo on the one hand, and CUK/OpCo on the other. Nor was there any evidence of any communications between OpCo and “the exec”, or between “the exec” and SSD/PropCo.

89. Under Framework Agreement and the Agreement for Lease, it is SSD (and not PropCo) which has the obligation to prepare the design and specification for Priors House and to appoint the professional team (and we note that AECOM’s consultancy agreement is with SSD and not PropCo). SSD (and not PropCo) is responsible for procuring that the contractor builds Priors House and is treated as the only client for the purposes of the CDM Regulations 2007. It is SSD (and not PropCo) that enters into the Building Contract with Thomas Vale Construction plc. Under the terms of the agreements, it is SSD (and not PropCo) that has responsibility for the delivery of Priors House in accordance with the design and specifications (although we note that SSD is released from liability upon the issue of a Certificate of Making Good Defects). And as SSD has no employees of its own, it outsources its obligations to OpCo under the Technical Services Agreement. There is no documentary evidence to suggest that PropCo was in any way actively involved in the development process, beyond executing the Agreement for Lease and the Lease, and paying the bills. There is no documentary evidence suggesting that PropCo was involved in any way in the selection and purchase of FF&E (beyond payment of invoices addressed to it). In this context we note that AECOM's certificate of practical completion gives PropCo’s address as "c/o Care UK" at OpCo's address in Colchester, and AECOM's covering letter to Thomas Vale Construction plc (setting out the additional works needed to be done after practical completion), was copied to Justin Daley of Care UK, and not to PropCo. Mr Daley is a construction project manager employed by OpCo. The fact that AECOM copied their correspondence to an OpCo manager supports our finding that it was OpCo (having delegated authority to act for SSD under the Technical Services Agreement) to whom AECOM reported. According to Mr Prior’s evidence, there are four individuals employed within OpCo’s construction team, of whom Mr Daley is one. His job is to ensure that the building meets the specifications set out in the associated plans and the mechanical and electrical engineering specifications. He will discuss this with AECOM, who will then deal with the contractor. Mr Prior did not know whether AECOM “fed back” to PropCo - and there is no evidence that it did so.

90. There is a conflict between Mr Prior’s and Mr Rosenberg’s evidence as to whether AECOM oversaw the fit-out of the FF&E items. Mr Rosenberg’s evidence was that AECOM supervised the sourcing and installation of FF&E. Mr Prior’s evidence was that AECOM only became involved if the installation of an item of FF&E needed to be integrated into the construction of the care home (such as a servery counter in the dining room). The services provided by AECOM under the terms of their consultancy agreement relate solely to the construction of the Prior House building and grounds - the agreement does not include any services relating to the FF&E or fitting-out. There is no documentary evidence to suggest that AECOM had any involvement in the selection or installation of FF&E. As Mr Rosenberg had not been involved in the procurement of FF&E or its installation, and as there is nothing in the terms of AECOM’s consultancy agreement that corroborates Mr Rosenberg’s evidence, we have no hesitation in preferring the evidence of Mr Prior in this respect. We find that OpCo (and not AECOM) was responsible for sourcing and overseeing the fit-out of the FF&E at Priors House.

91. We also note that Mr Prior’s description of AECOM being on “both sides” is inconsistent with the terms of their consultancy agreement with SSD. Although a copy of the building contract with Thomas Vale Construction plc (“the Building Contract”) was not included in the bundle, as an expert tribunal familiar with property development, we have some familiarity with the operation of JCT Design and Build contracts and are aware that an employer’s representative is required to act impartially when issuing certificates - but it is clear that in all other respects AECOM owed their duties to SSD, and not to Thomas Vale Construction plc, the building contractor, and so find. We find that AECOM did not act “on both sides”.

92. We find that the evidence of both Mr Rosenberg and Mr Prior relating to the development of Priors House in the period before practical completion are inconsistent with the provisions of the documentary evidence. We find that the limited documentary evidence before us is more reliable than the evidence of both Mr Rosenberg and Mr Prior, and we draw adverse inferences from the absence of other documentary evidence (such as copies of communications and minutes of meetings). We find that the reality was that there was no need for OpCo to liaise with SSD or PropCo, as SSD had delegated all decision making relating to the development of Priors House to OpCo. And we find that AECOM took its instructions from OpCo, in its capacity as the service provider to SSD (AECOM’s client under its consultancy agreement).

93. Mr Prior’s evidence was that PropCo provided a 10-year warranty on FF&E under the terms of the Lease (or the Agreement for Lease). This evidence broke down under cross-examination and we find that there is nothing in any of the agreements that amounts to PropCo providing a “warranty” in respect of any item of FF&E, and that Mr Prior’s statement that there is any such warranty is wrong.

94. More generally, we find that much of Mr Prior’s evidence is just wishful thinking on his part. He had no real knowledge or understanding of the legal and contractual relationships between the parties, and his evidence about these relationships and the communications that occurred amounts to what he thought was or ought to have been the case, rather than what actually occurred (based on first-hand knowledge). Save to the extent that Mr Prior’s evidence is self-evidently true or uncontested, or is corroborated (for example, by Mr Metcalfe, by photographs, or by documents), we place no reliance upon it.

95. We also place little reliance upon Mr Rosenberg’s evidence. Much of his evidence related to periods prior to his joining the businesses, and he provided no basis for his beliefs as to what occurred prior to him joining. His evidence as to the economic reasons why opco/propco arrangements are used is consistent with our own knowledge (as an expert tribunal) of these kinds of arrangements. However, he had no first-hand knowledge about the development of Priors House or the FF&E, and we place no reliance on this aspect of his evidence, save to the extent that it is corroborated by documentary evidence.

96. Mr Metcalfe’s evidence primarily related to the background to the making of the VAT assessments, and to his inspection of the FF&E at Priors House. His evidence as to the manner in which FF&E was installed was entirely consistent with that of Mr Prior, and we find that it is reliable.

Issues in this Appeal

97. The FF&E in dispute fall into two broad categories:

(1) FF&E which are in some manner fixed, attached, or installed in Priors House, which HMRC submit are “incorporated” and which PropCo submits are “loose”. This includes items such as wardrobes and bookcases.

(2) FF&E which are on any basis “loose” (and not “incorporated”), this includes a wide range of items, such as chairs and tables, beds, linen, kitchen equipment, crockery, and general household goods, first aid kits, hairdressing kits, J-Cloths, puzzles, photocopier consumables and bird tables.

98. HMRC made its assessment on two separate bases, these are described as being the “input tax issue” and the “output tax issue”.

99. The input tax issue concerns PropCo’s entitlement to credit for input tax incurred on the purchase of FF&E, and whether the entitlement to credit is blocked by the operation of the “Builder’s Block”.

100. The output tax issue is whether PropCo should have charged output tax on its supply of the FF&E to OpCo. HMRC argue that any loose FF&E not blocked by the Builder’s Block must be treated as separately supplied from the grant of the major interest in the building. Output tax is therefore chargeable on the FF&E. PropCo submits that no output tax arises on the basis that the FF&E forms part of a single supply of Priors House, the principal element of which was the zero-rated grant of a major interest in the Priors House building.

101. We therefore have two broad issues to determine.

102. The first is the input tax issue - to what extent is PropCo prevented from claiming credit for input tax on FF&E because of the operation of the Builder’s Block?

103. The second is the output tax issue - was the FF&E supplied by PropCo to OpCo as an element of a single supply - the principal element of which was the zero-rated grant of a major interest in the Priors House building?

104. HMRC’s assessments were made on the basis that

(a) the FF&E was supplied to PropCo in the same VAT accounting period as the FF&E were supplied by PropCo to OpCo, and

(b) the (VAT exclusive) value of the supply of FF&E to PropCo is the same as the (VAT exclusive) value of the supply of FF&E by PropCo. In other words, there is no “margin” between the price PropCo buys FF&E and sells it.

105. The legal burden of proof falls on PropCo in relation to all issues.

106. In considering these issues, it is not disputed that the FF&E was purchased by PropCo for onward supply to OpCo. This is evidenced by, amongst other things, the invoices for the FF&E which were addressed by Renray (and the other suppliers) to PropCo. It is not disputed that PropCo paid these invoices. We agree and find that PropCo purchased the FF&E with the intention of making an onward supply of the FF&E to OpCo, and that PropCo actually supplied the FF&E in dispute in this Appeal to OpCo.

107. Nor is there any dispute that the initial grant of the Lease was the grant of a major interest in land falling within Item 1(a)(ii) of Group 5, Schedule 8, VAT Act, and is therefore a zero-rated supply. Again, we agree and find that the grant of a lease of the Priors House building and associated land on the terms of the Lease was the grant of a major interest in land by PropCo to OpCo.

108. At the risk of stating the obvious, Priors House is located in England. The Framework Agreement, the Technical Services Agreement, the Lease and AECOM’s consultancy agreement are all expressly governed by English law. Curiously, the Agreement for Lease does not include a jurisdiction clause, but it will be governed by English law by virtue of the Rome I Regulations (Regulation (EC) No 593/2008) which were applicable at the relevant times.

109. Mr Macnab informed us that HMRC had taken a pragmatic position when raising its assessments in respect of items of FF&E that it considered were both incorporated in Priors House and subject to the Builder’s Block. HMRC had treated these items as being part of a single composite supply of the Priors House building. As regards other items, HMRC had raised its assessments on the basis that the value of the supply made by PropCo to OpCo was the same as the cost of the item to PropCo.

The Legislation

Output tax liability

110. Section 1 VATA provides:

1.— Value added tax.

(1) Value added tax shall be charged, in accordance with the provisions of this Act—

(a) on the supply of goods or services in the United Kingdom (including anything treated as such a supply) […]

111. Section 4 VATA provides

4.— Scope of VAT on taxable supplies.

(1) VAT shall be charged on any supply of goods or services made in the United Kingdom, where it is a taxable supply made by a taxable person in the course or furtherance of any business carried on by him.

(2) A taxable supply is a supply of goods or services made in the United Kingdom other than an exempt supply.

112. Section 30 VATA provides

30.— Zero-rating.

(1) Where a taxable person supplies goods or services and the supply is zero-rated, then, whether or not VAT would be chargeable on the supply apart from this section—

(a) no VAT shall be charged on the supply; but

(b) it shall in all other respects be treated as a taxable supply;

and accordingly the rate at which VAT is treated as charged on the supply shall be nil.

(2) A supply of goods or services is zero-rated by virtue of this subsection if the goods or services are of a description for the time being specified in Schedule 8 […]

113. Schedule 8, Group 5, VAT Act specifies the following descriptions of goods or services for the purposes of zero-rating:

|

Item No |

|

|

1 |

The first grant by a person—

(a) constructing a building—

[…]

(ii) intended for use solely for a relevant residential […] purpose; […]

of a major interest in, or in any part of, the building, dwelling or its site. |

|

2 |

The supply in the course of the construction of—

(a) a building designed as a dwelling or number of dwellings or intended for use solely for a relevant residential purpose or a relevant charitable purpose;

[…] |

|

4 |

The supply of building materials to a person to whom the supplier is supplying services within item 2 or 3 of this Group which include the incorporation of the materials into the building (or its site) in question. |

|

Notes |

|

|

(4) |

Use for a relevant residential purpose means use as

[…]

(b) a home or other institution providing residential accommodation with personal care for persons in need of personal care by reason of old age, disablement, past or present dependence on alcohol or drugs or past or present mental disorder;

[…] |

|

(12) |

Where all or part of a building is intended for use solely for a relevant residential purpose or a relevant charitable purpose—

(a) a supply relating to the building (or any part of it) shall not be taken for the purposes of items 2 and 4 as relating to a building intended for such use unless it is made to a person who intends to use the building (or part) for such a purpose; and

(b) a grant or other supply relating to the building (or any part of it) shall not be taken as relating to a building intended for such use unless before it is made the person to whom it is made has given to the person making it a certificate in such form as may be specified in a notice published by the Commissioners stating that the grant or other supply (or a specified part of it) so relates.

[…] |

|

(14) |

Where the major interest referred to in item 1 is a tenancy or lease—

(a) if a premium is payable, the grant falls within that item only to the extent that it is made for consideration in the form of the premium; and

(b) if a premium is not payable, the grant fails within that item only to the extent that it is made for consideration in the form of the first payment of rent due under the tenancy or lease. |

114. Section 96(1) VAT Act provides that-

“major interest”, in relation to land, means the fee simple or a tenancy for a term certain exceeding 21 years […]

115. Paragraph 4, Schedule 4, VAT Act provides that the grant of a major interest in land is a supply of goods.

Input tax credit

116. As regards credit for input tax, s25 VAT Act provides:

25.— Payment by reference to accounting periods and credit for input tax against output tax.

(1) A taxable person shall—

(a) in respect of supplies made by him,

[…]

account for and pay VAT by reference to such periods (in this Act referred to as “prescribed accounting periods”) at such time and in such manner as may be determined by or under regulations and regulations may make different provision for different circumstances.

(2) Subject to the provisions of this section, he is entitled at the end of each prescribed accounting period to credit for so much of his input tax as is allowable under section 26, and then to deduct that amount from any output tax that is due from him.

[…]

(7) The Treasury may by order provide, in relation to such supplies … as the order may specify, that VAT charged on them is to be excluded from any credit under this section […]

117. Article 6, Value Added Tax (Input Tax) Order 1992, provides as follows:

Disallowance of input tax

6.—Where a taxable person constructing, or effecting any works to a building, in either case for the purpose of making a grant of a major interest in it or any part of it or its site which is of a description in Schedule 8 to the Act, incorporates goods other than building materials in any part of the building or its site, input tax on the supply, acquisition or importation of the goods shall be excluded from credit under section 25 of the Act.

118. Article 2 of the Builder’s Block defines “building materials” by reference to Notes 22 and 23 to Schedule 8, Group5, VAT Act

‘building materials’ means any goods the supply of which would be zero-rated if supplied by a taxable person to a person to whom he is also making a supply of a description within either item 2 or item 3 of Group 5.

119. Notes 22 and 23 of Schedule 8, Group 5, VAT Act provide as follows:

(22) “Building materials”, in relation to any description of building, means goods of a description ordinarily incorporated by builders in a building of that description, (or its site), but does not include—

(a) finished or prefabricated furniture, other than furniture designed to be fitted in kitchens;

(b) materials for the construction of fitted furniture, other than kitchen furniture;

(c) electrical or gas appliances, unless the appliance is an appliance which is—

(i) designed to heat space or water (or both) or to provide ventilation, air cooling, air purification, or dust extraction; or

(ii) intended for use in a building designed as a number of dwellings and is a door-entry system, a waste disposal unit or a machine for compacting waste; or

(iii) a burglar alarm, a fire alarm, or fire safety equipment or designed solely for the purpose of enabling aid to be summoned in an emergency; or

(iv) a lift or hoist;

(d) carpets or carpeting material.

(23) For the purposes of Note (22) above the incorporation of goods in a building includes their installation as fittings.

Operation of the Builder’s Block

120. The effect of the Builder’s Block is to block claims for input tax on incorporated FF&E unless those items of FF&E are “building materials”.

121. This means that PropCo can only claim credit for input tax on items of FF&E supplied to OpCo if (broadly) the item of FF&E:

(1) has not been incorporated into the Priors House building; or

(2) is an item of “building materials” that has been incorporated into the Priors House building; in other words, the incorporated item is both

(a) of a description ordinarily incorporated by builders into care homes, and

(b) not expressly excluded because it is furniture (other than kitchen furniture), a gas/electrical appliance, or carpets

122. There are therefore two elements of the Builder’s Block that we need to consider:

(1) The extent to which the FF&E have been “incorporated” into Priors House for the purposes of the Builder’s Block; and

(2) Whether “incorporated” FF&E were “building materials” (or whether such items were excluded from being building materials).

Were items of FF&E incorporated into Priors House?

123. The law relating to the application of the Builder’s Block was decided definitively in the decisions of the Upper Tribunal in Taylor Wimpey v HMRC (No 1) [2017] STC 639 and Taylor Wimpey v HMRC (No 2) [2018] STC 689. As decisions of the Upper Tribunal, they are binding upon us. These decisions related primarily to the supply of kitchen appliances (“white goods”) as part of the sale a newly built residential home.

124. In Taylor Wimpey 1, the Upper Tribunal drew a distinction between the English land law concept of a fixture, and “incorporation” for the purposes of VAT:

[98] As to “installation as fittings”, we do not consider that the word “fitting” has any legally established meaning. It means, in substance, no more than a chattel somehow attached to the building where the degree of attachment is not sufficient, on the facts of the particular case, to constitute the item as a fixture. In the 1995 Order there is, of course, an express provision which brings items installed as fittings into the concept of “incorporation”. For our part, we do not think that that is to stretch the concept incorporation. And just as the express provisions of the 1995 Order do not stretch the concept of incorporation, so too, it is a perfectly natural use of the word “incorporates” in earlier iterations of the Builder's Block to include within its concept the installation of a chattel as a fitting. It will be necessary, in a given case, to consider whether something has been installed as a fitting, or whether it is a mere chattel, but we consider that assistance may be derived from considering the question not solely from the perspective of whether something may be described as “a fitting”, but whether it is installed as such. If something requires installation, that will, in our view, often be an indication that it falls to be considered to be a fitting.

[…]

[101] The purpose of the Builders’ Block is to block recovery of input tax on all components of a building other than the excepted, core, items. It would be inconsistent with this purposive approach to construe the Builders’ Block in a way that would exclude items installed as fittings from being regarded as incorporated in the building, with the result that such fittings would be zero-rated as part of the single supply with the dwelling and the input tax on those fittings would be recovered. That would have the consequence, at least prior to 1 March 1995, that installed fittings would have the benefit of recovery of input tax, but fixtures which were not ‘core’ in the sense of not having been ordinarily installed by builders would not benefit from recovery. Adopting a purposive approach to the construction of ‘incorporated’, we find that the expression cannot be limited to fixtures, but must include items installed as fittings before as well as after the 1995 Order.

[…]

[111] In our judgment, therefore, the test of incorporation is not determined by reference to the English land law of fixtures, nor by whether the item is part of the single zero-rated supply for VAT purposes. An item will be incorporated in a building if it is a fixture, and also if it is installed as a fitting. That does not depend on nice distinctions of land law, and whether something is part of the land. Nor does it involve an enquiry into whether the item is part of the single supply of the dwelling, either because it is part of the building or on CPP principles; that is a pre-condition for the Builders’ Block becoming material in a given case, but it does not determine the application of the block.

[112] That leaves the question of the criteria that should be applied in order to determine if an item, which is not a fixture, is installed as a fitting. The test must be such as to be consistent with the statutory language of incorporation in a building. Without setting a prescriptive test, there must in our view be a material degree of attachment to the building, albeit less than the degree of annexation required for something to be a fixture. In our judgment mere attachment to an electricity supply by a removable plug is not, on its own, sufficient for the item to be regarded as installed as a fitting, or incorporated. Some other feature or features of installation is necessary, whether by housing the item in a particular structure, or by fixing the item in a manner designed to be other than temporary either to a physical part of the structure or to a supply of electricity, gas or water or means of ventilation or drainage.

[…]