Introduction

1. This is an appeal against a decision of the First Tier Tribunal (Property Chamber) (“FTT”) dated 1 September 2019 determining the premium payable for the extension of a leasehold interest with 55.95 years unexpired in 5 Mansard Manor and Garage 10, Christchurch Park, Sutton, Surrey SM2 5UB. The FTT determined the premium to be £30,264, based on an existing lease value of £210,395 and relativity of 82.22%.

2. The appellant is the head leaseholder, Deritend Investments (Birkdale) Limited and the respondent lessee is Ms Kornelia Treskonova.

3. The FTT refused permission to appeal. On 26 November 2019 this Tribunal granted permission and the appeal has been conducted as a review of the FTT’s decision under the written representations procedure.

4. Mr Piers Harrison made written representations on behalf of the appellant, relying upon expert evidence from Mr Robin Sharp FRICS which had been given to the FTT. Ms Gemma de Cordova made written representations on behalf of the respondent in response to the application for permission to appeal, which stood as the grounds of opposition to the appeal. The respondent relied upon expert evidence from Mr Wilson Dunsin FRICS.

Statutory provisions

5. Section 56 of the Leasehold Reform, Housing and Urban Development Act 1993 (“the Act”) provides that where a qualifying tenant of a flat has a right to acquire a new lease, and gives notice of claim in accordance with section 42, a new lease extending the existing lease by 90 years shall be granted and accepted in substitution of the existing lease upon payment of the premium payable under Schedule 13.

6. Under paragraph 2 of Schedule 13, the premium payable for the new lease is the aggregate of three sums: the diminution in the value of the landlord’s interest resulting from the grant, the landlord’s share (50%) of the marriage value, and any amount of compensation payable to the landlord under paragraph 5 (in this case agreed to be nil). In calculating the value of the landlord’s interest and his share of marriage value, any increase in the value of the flat which is attributable to an improvement carried out by the tenant at his own expense is to be disregarded.

Facts

7. The subject property is a one-bedroom flat of 469 sqft on the second floor of a 1950s purpose-built block of 12 flats over three storeys. The premises include a single garage (No. 10) within a block of garages. There are communal gardens and car parking.

8. The appellant holds an intermediate leasehold interest of 999 years from 25 October 2010.

9. The respondent holds a leasehold interest granted from 24 June 1975 for a term of 99 years. The ground rent is £60 per annum, rising to £120 per annum from March 2040.

10. Notice of her claim was given by the respondent to the appellant on 10 July 2018, which is the valuation date. At that date the original term of the lease had 55.95 years unexpired.

The FTT decision

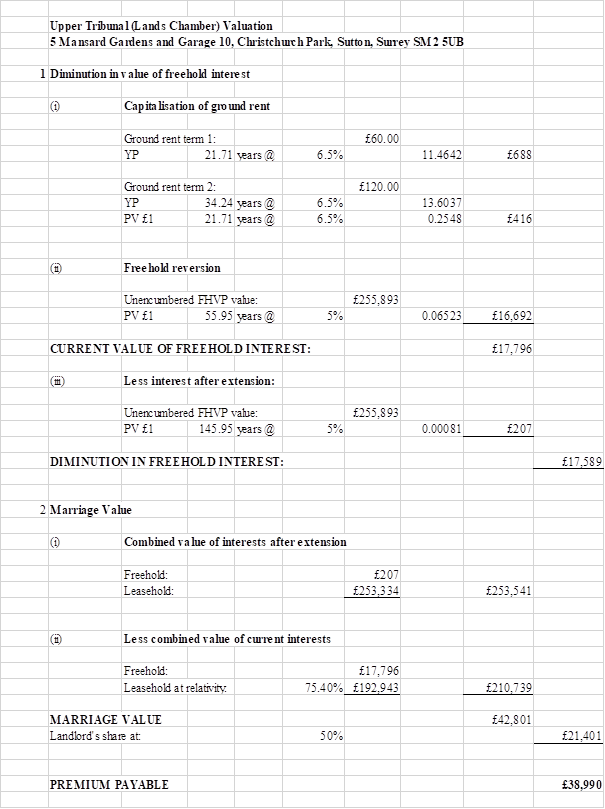

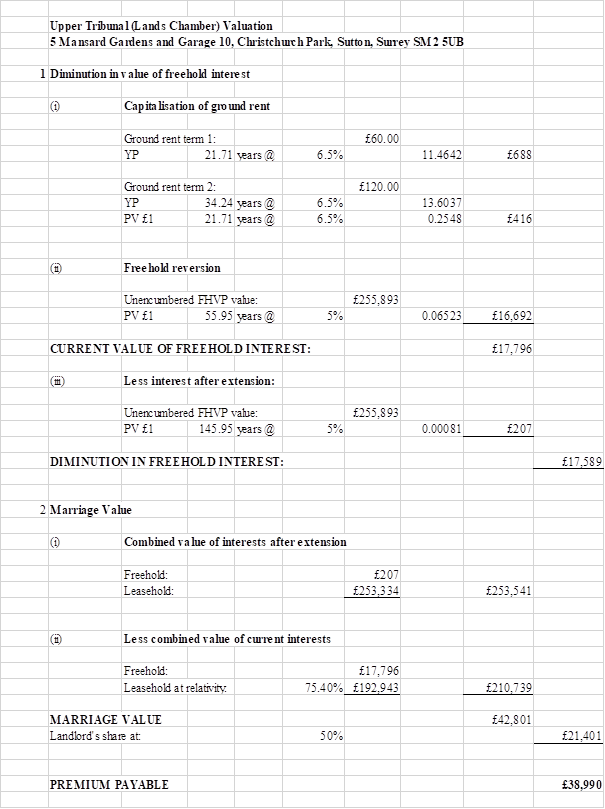

11. The parties had agreed all the elements of the calculation of the premium payable for the lease extension, with the exception of the relationship, or “relativity”, to be applied to the freehold vacant possession value (“FHVP”) of £255,893 to establish the existing leasehold value and thus marriage value.

12. In the absence of market transactions in similar flats with similar unexpired terms to the subject property, both parties relied on graphs of relativity to establish existing leasehold value.

13. The respondent’s expert, Mr Dunsin, determined relativity using the average of five Greater London and England graphs included in the RICS Research Report on Graphs of Relativity, published in 2009 (“RICS 2009 graphs”). The five graphs were those prepared by Beckett and Kay, South East Leasehold, Nesbitt and Co, Austin Gray, and Andrew Pridell Associates Ltd. For a lease of 55.95 years, this produced a relativity of 82.22% and a premium of £30,264.

14. The appellant’s expert, Mr Sharp, determined relativity by looking first at the Savills 2016 (unenfranchiseable) graph of relativity (“Savills 2016 graph”) and the Gerald Eve 2016 (unenfranchiseable) graph of relativity (“Gerald Eve 2016 graph”), which respectively indicated relativities of 75.5% and 75.3%, for a lease of 55.95 years. Mr Sharp took the average at 75.4%. He then looked at the Beckett and Kay (unenfranchiseable) 2017 mortgage-dependent graph (“Beckett and Kay 2017 graph”), which had been updated from the edition included in the RICS 2009 graphs. This indicated a relativity of 67% for 55.95 years. Mr Sharp took an average of the two figures of 75.4% and 67% to produce a relativity of 71.2% and a premium of £44,381.

15. The FTT commented that it found the evidence of both experts to be unsatisfactory; Mr Dunsin’s because of the inconsistency of his evidence in this case with evidence he had given on a previous occasion; Mr Sharp’s because two of his three graphs were for Prime Central London (“PCL”) which the FTT considered inappropriate in relation to a small one-bedroom flat in Sutton. Relying on its own knowledge and judgement it considered the least unsatisfactory approach was to adopt an average of the five RICS 2009 graphs (the same approach as Mr Dunsin) giving relativity of 82.22% and a premium of £30,264.

16. One day before the FTT issued its decision this Tribunal published its own decision in Trustees of Barry and Peggy High Foundation v Zucconi [2019] UKUT 242 (LC), which also concerned leasehold relativity. The FTT’s attention was drawn to the Tribunal’s decision by the appellant when it applied for permission to appeal, when it would still have been possible for it to review its own decision. In its refusal of permission the FTT stated that it was not bound to apply decisions of the Tribunal where the facts and evidence before it differed and on which no argument was heard or submissions made by the parties. It therefore declined to review its decision.

17. Permission to appeal was granted by the Tribunal on 26 November 2019.

Submissions for the appellant

18. Mr Harrison submitted that Mr Sharp’s use of the three most recent graphs of relativity should be preferred to the FTT’s reliance on an average of the RICS 2009 graphs for a number of reasons. First, the Savills 2016 graph and Gerald Eve 2016 graph were current graphs that had been updated following comments made by the Tribunal in Trustees of the Sloane Estate v Mundy [2016] UKUT 223 (LC) on the shortcomings of earlier versions. A Savills 2015 graph, which replaced the 2002 version, had been enhanced in 2016 by the inclusion of a relativity curve for unenfranchiseable leases. The Gerald Eve 2016 graph of relativity for unenfranchiseable leases replaced their 1996 version, which had been viewed as over-stating relativity by reference to current markets.

19. Noting that these two graphs related to PCL, Mr Sharp had suggested that relativity in an Outer London suburb, such as Sutton, ought to be lower than in PCL because the Outer London market would be more mortgage-dependent and less international. He also considered that the effect of Act rights was greater in the suburbs than in PCL. Mr Sharp suggested that these differences should be addressed by averaging the most reliable PCL graphs with the most reliable suburban graph. This he said was the Beckett and Kay 2017 graph which benefited from being the only one of the five Greater London and England graphs from the RICS 2009 Report to have been updated since the Tribunal’s observations in Mundy. Mr Sharp therefore considered that using these three graphs would be more reliable than averaging the RICS 2009 graphs, four of which were historic, having been produced prior to the financial crash of 2008 and before mortgage lending criteria became more stringent.

20. In his evidence to the FTT Mr Sharp had made reference to Mallory v Orchidbase [2016] UKUT 468 (LC), where the unexpired term was 57.68 years and the Tribunal determined relativity, on the basis of transaction evidence, to be 76.25%, which was below the figure of 76.7% for that term in the Savills 2016 graph. He also referred to Reiss v Ironhawk Ltd [2018] UKUT 311 (LC), where the unexpired term was 75.23 years and the relativity was determined at 86.9%, again below the Savills 2016 figure of 87.2%.

21. Mr Sharp’s evidence on relativity had included reference to 10 FTT decisions made between November 2016 and August 2018 concerning properties in Sutton, Croydon and Bishopric Horsham. He had given evidence in each of these cases. The range of unexpired terms was between 56 and 60 years and in all cases the relativity was set at a level below that to be found in the Savills 2016 graph. In particular, the three properties in Sutton had unexpired terms between 56 and 57 years, close to the unexpired term of 55.95 years for the subject property, and the determined relativities, ranging between 71.8% and 72.43%, were based on transaction evidence. This was said to support Mr Sharp’s point that relativity outside PCL is lower than that indicated in the Savills 2016 graph.

22. Mr Harrison also commented that the Savills June 2016 graph of relativities for enfranchiseable leases, from which the unenfranchiseable graph is derived, contains relatively sparse data for leases with around 56 years unexpired. The data points that are shown at that period sit below the line of best fit and Mr Harrison invited the conclusion that, even in PCL, relativity taken from the Savills 2016 graphs may be overstated for unexpired leases of around 56 years. This was not a point made by Mr Sharp.

23. Turning to the evidence of Mr Dunsin, Mr Harrison suggested that his report did not conform with the RICS practice statement and guidance note on surveyors acting as expert witnesses, in particular in omitting a statement confirming that the report “has drawn attention to all material facts which are relevant”. Mr Harrison pointed out a contradiction in Mr Dunsin’s views of the inappropriateness of PCL relativity graphs for properties outside of PCL in this case and in his evidence to the FTT in 2018 in a case concerning property in SW16 where he had acted for the freeholder and preferred the Savills 2016 graph over the 2009 graphs. Mr Harrison also pointed out Mr Dunsin’s selective reference to FTT and Tribunal cases in his evidence, omitting mention of cases where the PCL graphs were adopted outside of PCL.

24. Finally, Mr Harrison relied on the Tribunal’s decision in Zucconi, which had been published the day before the FTT’s decision in this case. The Tribunal (Mr A J Trott FRICS) stated at [27]:

“In my opinion the FTT did not pay proper regard to the more recent cases, outside of prime central London, where the Savills enfranchiseable and unenfranchiseable graphs have been preferred by the Tribunal to the use of an average of RICS 2009 graphs.”

25. Whilst the Zucconi case did not establish that relativity outside PCL should be lower than that shown by those graphs, Mr Harrison submitted that in the absence of either transaction evidence, or the equivalent of a Savills 2016 graph for areas outside of PCL, the best evidence, as relied on by Mr Sharp, comprised the decisions of other tribunals, derived from or based in part on sales of short leases in the vicinity of Sutton.

26. In the application for permission to appeal, Mr Harrison also cited the Tribunal’s decision in Reiss, where the Savills 2015 graph was used in relation to a property outside PCL, and pointed out that the FTT had been made aware of this case but did not take it into account. He did not develop the point in his written representations for this appeal.

Submissions for the respondent

27. In her response to the application for permission to appeal, which formed the respondent’s only submissions on the appeal, Ms de Cordova reiterated the FTT’s comment that it had made its decision using its knowledge and judgement. Although adopting the same approach as Mr Dunsin, it had criticised his report and had not relied on his evidence, instead arriving at the same conclusion by their own reasoning.

28. On the FTT’s disregard of the Tribunal’s approach in Reiss, Ms de Cordova submitted that it was not bound to follow it, given that the valuation date in this case was 10 July 2018, which preceded the date of the Reiss decision in September 2018. Furthermore, the circumstances of that appeal were quite different and concerned a figure determined by the FTT which was inconsistent with the totality of the evidence and “obviously too low”.

29. Turning to the FTT’s adoption of an average of the RICS 2009 graphs, with no regard to the Savills and Gerald Eve 2016 graphs, Ms de Cordova submitted that, unlike the situation in Zucconi where the FTT did not consider the PCL graphs, paragraph 17 of the FTT’s decision made clear that it had considered their relevance and rejected them when it said “… the tribunal does not consider that it is appropriate to use PCL graphs in relation to a small one-bedroom flat in Sutton.” It had also given its reasons for excluding reliance on the Beckett and Kay revised graph, stating that it was not “appropriate to identify and rely upon one only of the RICS Greater London graphs.”

30. The appellant’s application for permission to appeal had cited the Tribunal cases of Re Midland Freeholds Limited’s and Speedwell Estates Limited’s Appeals [2017] UKUT 463 (LC) and Oliyide v Elmbirch Properties Plc [2019] UKUT 190 (LC) in which the Tribunal had regard to PCL graphs when determining premiums for properties outside PCL. Ms De Cordova noted that in Re Midlands Freeholds the Tribunal’s decision concerned specifically the adjustment to be made for Act rights in areas other than PCL. She suggested Oliyide had no application to the facts of the present case.

Discussion

31. At paragraph 169 of its decision in Mundy the Tribunal provided guidance on the approaches available to determine the relativity of a lease without rights under the 1993 Act where there is no reliable market transaction evidence:

“One possible method is to use the most reliable graph for determining the relative value of an existing lease without rights under the 1993 Act. Another method is to use a graph to determine the relative value of an existing lease with rights under the 1993 Act and then to make a deduction from that value to reflect the absence of those rights on the statutory hypothesis.”

32. Both methods require evidence or agreement on FHVP value. The second method also requires evidence on which a deduction for Act rights can be determined. When Mundy was decided, the Gerald Eve 1996 graph was the most widely consulted graph of relativity for leases without Act rights. The Savills 2002 graph, and its emerging 2015 successor, provided relativity for leases with Act rights and, by comparison with the Gerald Eve graph, a guide to the adjustment to be made for Act rights at different lease lengths. The Savills graph was also used in the market to determine adjustments to transaction evidence of different lease lengths to arrive at FHVP value. A detailed review of these and other PCL graphs was provided at Appendix C to Mundy. The assistance which the graphs provided to the market was acknowledged, but reservations were expressed about the current reliability of the graphs.

33. Prompted by Mundy, the Savills 2015 graph was revised in 2016 by the inclusion of a relativity curve for unenfranchiseable leases and the Gerald Eve 2016 graph for unenfranchiseable leases replaced the 1996 version. Both are freely available on the internet for use by the market.

34. The critical issue for the FTT was the contention that, because the Savills and Gerald Eve 2016 graphs were derived solely from PCL data, their use was not appropriate (either wholly or in part) for determining relativity outside of PCL. For the appellant, Mr Sharp considered that the PCL graphs should not be used on their own for property outside PCL and that they should be combined with the 2017 revision of the Beckett and Kay mortgage-dependent graph. For the respondent, Mr Dunsin’s concern was that “the market and the relativity in Sutton is completely different from the market and the relativity in PCL”. In his view the PCL graphs were too low so they must be disregarded in favour of an average of the RICS 2009 graphs for Greater London and England which produced a higher relativity figure. The FTT adopted Mr Dunsin’s approach (although it appears to have done so independently of his evidence).

35. since Mundy the Tribunal’s decisions on relativity have all concerned properties outside PCL. The outcome of each case obviously depends on the particular facts, the elements of valuation which are in dispute, and the quality of evidence presented to the Tribunal by the parties, but the approach taken by the Tribunal serves as guidance which may be relied on in other cases. Reiss, Oliyide and Zucconi present a consistent pattern: in each case where transaction evidence was either unhelpful or unavailable, the recent PCL graphs were adopted as the most reliable and objective evidence of relativity.

36. In Reiss the Tribunal considered that the most reliable method of valuing the existing lease of a flat in North London was to use the 2015 Savills’ enfranchiseable graph which had been published by the valuation date, and to make an agreed deduction for the benefit of Act rights.

37. In Oliyide the Tribunal acknowledged that there were problems in using PCL graphs to determine relativity for property in the West Midlands, but, at [42], it nevertheless considered their use to be appropriate for the reasons given in Midlands Freeholds Ltd’s and Speedwell Estates Ltd’s Appeals [2017] UKUT 463 (LC) at paragraphs 37 to 43. The issue in that case concerned the quantification of the benefit of Act rights but in Oliyide the same approach was taken to the use of relativity graphs to determine the value of the current leasehold interest.

38. Zucconi, the Tribunal’s most recent decision on relativity, concerned, as here, property outside PCL where no transaction evidence was available. The two PCL graphs were described as “… the most reliable (and recent) graphs ...”. The Tribunal held that the FTT in that case had been wrong in principle to ignore the PCL graphs and to focus exclusively on the average of the RICS 2009 graphs. At paragraph [24] the Tribunal identified other outer London properties where PCL graphs had been used, saying:

“The fact that a graph is based on data from prime central London does not automatically invalidate its use outside that area; see, for instance, the use of the prime central London Cluttons Graph in Xue, where the appeal property was in Shepherd’s Bush; or in Sinclair Gardens, where the Tribunal referred to Savills 2015 Graph (see paragraph 62).”

39. The two PCL graphs are still rightly regarded as the most reliable and recent graphs of relativity. They provide objective evidence of relativity, based on a very large data set, and have been revised in light of close scrutiny by the Tribunal in Mundy. They should be considered as a starting point where no, or insufficient, transactional evidence has been submitted by the parties. They are not ideal, particularly for property outside PCL, but for the time being they provide the only treatment of relativity which can be regarded as reliable. Their use is always preferable to the use of an average of the RICS 2009 graphs.

40. A major criticism of the RICS 2009 graphs is that they overstate relativity in post financial crisis markets. Of the five component graphs averaged by the FTT only the Beckett and Kay mortgage dependent graph has been updated to take account of the very different circumstances which existed after 2009. The 2017 version of the Beckett and Kay graph places relativity at 55 years at 67%, compared with 79% in the 2009 graph. Where the authors themselves no longer consider their original graph reflects current relativity it is not possible to justify its continued use, which is what the FTT did in this case. Even if the current version had been substituted in calculating the average, the overall effect of the other four graphs would produce a result predominantly based on historic data.

41. The data in the RICS 2009 graphs is not only historic, but suffers variously from limitations of scale and source. The 2009 Beckett and Kay graph used opinion data, with no defined geographical area other than non-PCL. The South East Leasehold graph used analysis from 1997 of transaction data for flats in Bromley and Beckenham. The Nesbitt and Co graph used evidence of some 250 settlements and LVT decisions, for predominantly flats, between 1995 and 2008 in Greater London and a proportion of provincial towns. The Austin Gray graph used a mix of pre and post 1993 transactions, settlements and LVT decisions for some 250 flats, predominantly in Brighton and Hove. The Andrew Pridell Associates graph used a mix of opinion, settlements, transactions and LVT and Tribunal decisions for 500 flats in the south east and suburban London.

42. Taking an average result from the five graphs serves to merge the data sets numerically, but does not diminish their limitations in terms of geography, datedness and weak source material. We note from Mr Sharp’s evidence that the Beckett and Kay 2017 graph is said to be based on less than 100 sales, decisions and settlements and that the line is hand drawn. This graph therefore suffers equally from limitations of scale and source.

43. The weight which can be given to LVT decisions on relativity as evidence was considered by the Lands Tribunal in Arrowdell v Coniston Court (North) Hove Ltd [2007] RVR 39 at [37] and [38], as follows:

“In our judgment LVT decisions on relativity are not inadmissible, but the mere percentage figure adopted in particular cases is of no evidential value. The reason for this is that each tribunal decision is dependent on the evidence before it, and thus, in order to determine how much weight should be attached to the figure adopted in a decision, it would be necessary to investigate what evidence the LVT had before it and how it had treated it. Such a process of investigation is potentially lengthy, and it is inherently undesirable that LVT hearings should resolve themselves into rehearings of earlier determinations.

It is certainly understandable that valuers negotiating the settlement of an enfranchisement claim should have regard to LVT decisions on relativity, since these might seem to them to be the best guide of the likely outcome if they were unable to reach agreement… But the decisions themselves can constitute no useful evidence in subsequent proceedings."

44. The utility of settlement evidence was considered by the Lands Tribunal in Arbib v Cadogan [2005] 3 EGLR 139 at [127]:

“Three main criticisms can be made of settlements as valuation evidence. First, they are usually evidence only of the price agreed and not of the component parts of that price. Second, they may be affected by the "Delaforce" effect, that is to say the anxiety on the part of the tenant or landlord to reach agreement, even at a figure above or below the proper price, without the stress and expense of tribunal proceedings. Third, they tend to become self-perpetuating and a substitute for proper consideration and valuation in the particular case.”

45. The FTT’s statement, in refusing permission to appeal, that it was not bound to apply decisions of the Tribunal “where the facts and evidence before it differed” is a correct but incomplete description of its relationship to this Tribunal. One of the most important functions of this Tribunal is to give guidance on valuation practice, and the hierarchical relationship between tribunals requires the FTT to adhere to that guidance.

46. The FTT’s only explanation for disregarding the most recent graphs was that the use of PCL graphs was not “appropriate” for a small property outside PCL. As those graphs were the basis of the appellant’s case the FTT ought probably to have explained its view in a little more detail, whether or not it was aware of Zucconi and the other recent Tribunal decisions. We make no criticism of the FTT’s refusal to review its decision on the basis of a decision of this Tribunal published, no doubt, after it had finalised its own decision. The reasons it gave were perfectly proper, but they did not explain why the FTT did not take the 2016 PCL graphs themselves into account or why their use was not appropriate.

47. For a lease with 55.95 years unexpired, relativity derived from the Savills 2016 unenfranchiseable graph is 75.5% and from the Gerald Eve unenfranchiseable graph it is 75.3%. Mr Sharp averaged these figures at 75.4%, but considered that this relativity was still too high for a property in Sutton, where the market would be more mortgage-dependent and less international than the PCL market on which the graphs were based, resulting in reduced demand for leases of this length. For this reason he reduced the figure of 75.4% by averaging it with a much lower figure of 67% derived from the Beckett and Kay 2017 graph. If this approach was soundly based a more legitimate average would have been derived by attributing equal weight to all three graphs.

48. As we have noted above, the Beckett and Kay 2017 graph is the only one of the five RICS 2009 graphs to have been revised since the financial crash, but it has severe limitations and cannot be regarded as reliable. It not only sits conspicuously below the other RICS graphs but also significantly below the most recent and reliable 2016 PCL graphs. 67% by comparison with 75.4% is a relative difference of over 11% and simply to average two such different figures is to overlook, or disregard, all reasons for their difference. We view the Beckett and Kay 2017 graph as an outlier and we do not think it is safe to average a figure derived from the two most reliable and recent graphs with a conspicuously lower figure from a recent but much more limited data source.

49. In support of the contention that the relativity for the subject property should be lower than that derived from the PCL graphs, Mr Harrison submitted a number of alternative reasons, based on Mr Sharp’s evidence, which we review below.

50. The fact that in Orchidbase the Tribunal determined, on transaction evidence for a property outside of PCL, a relativity for an unexpired term of 57.68 years which was below the figure which would be derived from the Savills 2016 graph is not particularly significant. The difference between 76.25% and 76.7% is marginal and immaterial. The Tribunal did not need to consider relativity graphs in Orchidbase but the closeness of the relativity based on transactions to the figure derived from the Savills 2016 graph supported the use of that graph outside PCL without further adjustment.

51. The relativities on which Mr Sharp relied, taken from decisions of the FTT concerning properties in Sutton, Croydon and Bishopric Horsham, are not evidence to which we attribute weight (for the reasons given in Arrowdell).

52. Mr Harrison’s final submission on the overstating of relativity in the PCL graphs concerned the position of data points in the Savills 2016 graph for enfranchiseable leases (from which the relativity curve for unenfranchiseable leases was derived) where the unexpired period was around 56 years. This was not a point raised in evidence by Mr Sharp and does not speak directly to the concern regarding properties outside PCL. No doubt the Beckett and Kay graph and each of the five Greater London and England graphs, which were based on much smaller data samples, LVT decisions and opinion, contains similar gaps. We do not consider that the relative weakness of the evidence at different lease lengths justifies resort to evidence of much more doubtful quality.

53. In the absence of relevant transactional evidence, and with no reliable and up to date graph of relativity outside PCL, we do not consider the FTT was entitled to reject the PCL graphs in favour of an average of five outdated graphs with patent limitations in post financial crisis markets.

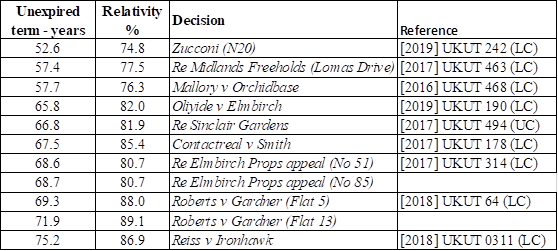

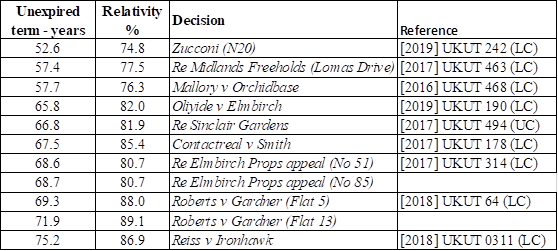

54. It is useful to consider the average relativity from the two PCL graphs in the context of other decisions of the Tribunal for leases outside PCL. The table below summarises the Tribunal’s decisions on relativity since Mundy, in order of unexpired lease term:

55. This overview provides general, not specific, guidance since every case is considered on its own merits and many of the decisions were based on transaction evidence in the locality. However, for a lease with 55.95 years unexpired it provides confidence that a relativity of 75.4%, derived from an average of the PCL graphs, is appropriate and that the FTT’s relativity of 82.22% is too high.

Determination

56. In our judgment the FTT was wrong as a matter of valuation practice to rely on an average of the RICS 2009 graphs and to ignore the more recent graphs for PCL, and the appeal is therefore allowed. We set aside the FTT’s determination.

57. In view of the relatively modest sum in issue we will reach our own conclusion on the basis of the material before the FTT, rather than remitting the issue to it for further consideration.

58. The guidance given by this Tribunal endorses the use of the Savills and Gerald Eve 2016 graphs where there is no transaction evidence, notwithstanding that the subject of the valuation is outside PCL. If persuasive evidence suggests that the resulting relativity is not appropriate for a particular location a tribunal would be entitled to adjust the figure suggested by the PCL graphs. The RICS 2009 graphs do not provide that persuasive evidence and, if it is to be found, it is likely to comprise evidence of transactions; if those are available it may be unnecessary to make use of graphs at all. In any event, no such persuasive evidence was presented to the FTT.

59. We are satisfied that the outcome justified by the evidence provided to the FTT was a determination based on the average of the two 2016 PCL graphs. For the reasons we have already explained we do not endorse Mr Sharp’s averaging of the resulting relativity figure by reference to the Beckett and Kay 2017 graph.

60. We therefore determine relativity at 75.4%.

61. The premium payable is £38,990 as shown in the attached appendix and we substitute that figure as the premium payable by the respondent for the new lease.

Martin Rodger QC Mrs Diane Martin MRICS FAAV

Deputy Chamber President

1 July 2020

APPENDIX