Creative Commons – The Next Generation: Creative Commons licence use five years on

Jessica Coates*

|

Table of Contents: 1. Background

1.1 About Creative Commons 1.2 The licences 2. How are the licences being used? 3. Who is using the Licences, and why? 3.1 First generation users 3.2 Second generation users 3.3.1 Non-profit and public sector users 3.2.1 Commercial services 4. Conclusion

|

|

Cite as: J Coates, "Creative Commons – The Next Generation: Creative

Commons licence use five years on", (2007) 4:1 SCRIPT-ed 72 @: <

http://www.law.ed.ac.uk/ahrc/script-ed/vol4-1/coates.asp >

|

© Jessica Coates 2007.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivative Works 2.5 Australia License. |

1. Background

1.1 About Creative Commons

Creative Commons is an international non-profit founded in 2001 by a group of US copyright experts – most notably, Stanford law professor, Lawrence Lessig.1 These experts became concerned that the default copyright laws that applied in most countries were restricting creativity in the digital environment by preventing people from accessing, remixing and distributing copyright material online. Of particular concern was the fact that, due to the rigidity and complexity of copyright in most jurisdictions, even those who wanted to make their copyright material more freely available were unable to do so without hiring a lawyer.

Taking inspiration from the free or open source software movement, the Creative Commons founders decided to create a ‘free culture’ by developing a set of licences that creators could use to make their creative material more freely usable without giving up their copyright.2 Like the open source licences, the Creative Commons licences would build upon the ‘all rights reserved’ model of traditional copyright to create a voluntary “some rights reserved” system.3 However, unlike the open-source movement, the licences would focus on content, not software – the text, music, pictures and films being distributed on the internet, rather than the tools being used for this distribution. They would be free, voluntary, flexible, and would not require a lawyer to translate them. The Creative Commons founders hoped that this would lead to the creation of a ‘digital commons’, a pool of creative material was free to be used, distributed and remixed by others, but only under certain conditions.

Although it is sometimes suggested otherwise, Creative Commons is not an anti-copyright movement. On the contrary, it bases its distribution model on the rights granted under copyright law, and the ability of the copyright owner to manage and control these rights. Rather, Creative Commons provides an alternative model for managing copyright in the digital environment. It aims to provide readily available and easy-to-use tools for those who wish to explore new business and distribution models, with the ultimate goal of encouraging innovation and creativity online.

1.2 The licences

The first Creative Commons licences were released in December 2002.

Since this time there have been several updated versions (2.0, 2.5

and even 2.1 in some jurisdictions), with the current being version

3.0, which was released on 32 February 2007.4

Despite these regular updates, the features of the six most commonly

used or ‘core’ licences, have remained relatively

constant over time. Each of these licences comes with certain base

rights (such as moral rights protection), along with optional

'licence elements'. These elements represent ways in which creators

may wish to restrict how their work can be used and include:

Attribution (BY) – This element has been compulsory in each of the core licences since version 2.0. Whenever a work is copied, redistributed or remixed under a Creative Commons licence, credit must be given to the original author.

Non-Commercial (NC) – Lets others copy, distribute, display, and perform the work — and derivative works based upon it — for non-commercial purposes only.

No Derivative Works (ND) – Lets others distribute, display, and perform only verbatim copies of a work, not derivative works based upon it.

Share Alike (SA) – Allows others to distribute, display and perform derivative works only under the same licence conditions that govern the original work.5

By selectively applying these elements creators are able to choosing between the following six licences6:

Attribution (BY) - This is the most accommodating of the Creative Commons licences, in terms of what others can do with the work. It lets others copy, distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, even commercially, as long as they credit the original author.

Attribution Non-commercial (by-nc) - Lets others copy, distribute, remix, tweak, and build upon the work, as long as it is for non-commercial purposes and they credit the original author.

Attribution Share Alike (by-sa) - This licence is often compared to open source software licences. It lets others remix, tweak, and build upon the work even for commercial purposes, as long as they credit the original author and license any derivative works under identical terms. All new works based on the original work will carry the same licence, so any derivatives will also allow commercial use and share alike remixing.

Attribution Non-commercial Share Alike (by-nc-sa) - Lets others remix, tweak, and build upon the work, as long as it is for non-commercial purposes, they credit the original author and they license any new creations under identical terms.

Attribution No Derivative Works (by-nd) - Allows use of a work in its current form for both commercial and non-commercial purposes, as long as it is not changed in any way or used to make derivative works, and credit is given to the original author.

Attribution Non-commercial No Derivative Works (by-nc-nd) - This is the most restrictive of the six core licences. It is often called the ‘advertising’ licence because it allows a work to be copied and shared with others, but only in its original form, for non-commercial purposes and where credit is provided to the original author.

In developing the Creative Commons system particular emphasis was placed on ease of use. Each of the licences is therefore accompanied by a ‘licence deed’, which sets out the major terms of the licence in plain English. This is the public face of the licence, and is intended to assist licensors and licensees alike to understand their legal rights and obligations. It is the first thing a person will see if they click on a Creative Commons licence button on a webpage; from there, they can access the full legal code of the licence. Other tools designed to increase ease of use of the Creative Commons system include the ‘licence generator’, a questionaire which automatically determines the most appropriate licence for a creator;7 and the ‘licence metadata’, which enables works badged with the Creative Commons licences to be identified by a range of search engines, including Google, Yahoo and Linux web browser Mozilla Firefox.8

2. How are the licences being used?

According to the latest statistics available from the Creative

Commons website, as at 1 June 2006 about 140 million web-objects were

badged with a Creative Commons licence.9

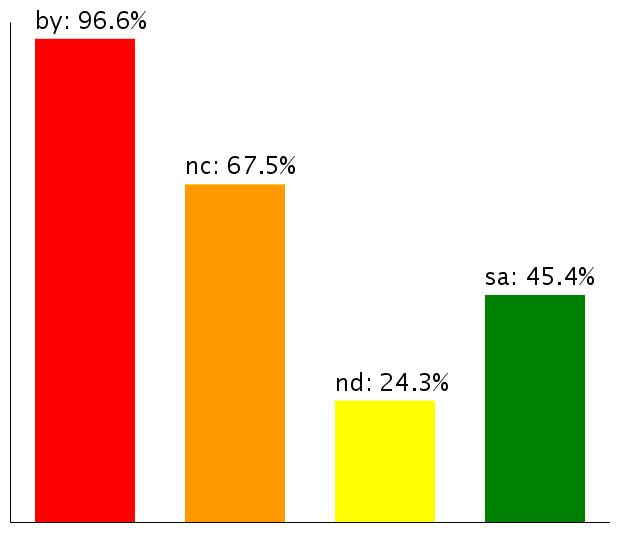

The table below sets out the proportional use of the licence elements

across these objects.

|

by = attribution |

Table 1: Distribution of licence properties across licences deployed10

As these figures indicate, of the optional licence elements –

Non-commercial, No Derivative Works and Share Alike – the most

popular is the Non-commercial element, with 67.5 percent of licensors

choosing to apply this to their works. This is unsurprising; while

many creators are happy to make their work available for private or

non-profit use, it is to be expected that most will baulk at the idea

of someone else making money from it without paying some

compensation. Less predictably, the next most popular licence element

is Share Alike, not No Derivative Works. This seems to go against an

instinctual assumption that most creators will choose to ‘protect’

the integrity of their work ie control reuses to prevent it from

being remixed in ways of which they do not approve.11

Instead it suggests that, even as the Creative Commons community has

grown from only a few thousand to millions of users, its members have

retained a strong focus on fostering creativity through reuse. This

is supported by the overall figures on licence use, with Attribution

Non-commercial Share Alike by far the most popular licence, being

chosen by 29.01 percent of all Creative Commons users; the next most

popular, Attribution Non-commercial No Derivative Works, is used by

only 17.81 percent.12

-

Element

Percentage usage – February 2005

Percentage usage –

June 2006

Non-commercial

74

67.5

Share Alike

49

45.4

No Derivative Works

33

24.3

Table 2: Proportional use of Creative Commons licence elements13

Looking at how these statistics are changing over time also provides interesting results. As Table 2 above shows, licensors appear to be gradually moving towards more liberal licences with fewer restrictions. Use of the Non-commercial licence element, for example, has fallen from 75 percent of all licences in 2005 to its current level of just over two thirds. Use of the No Derivative Works and Share Alike elements has also dropped over this period, with the use of No Derivatives falling by almost a third.

Although the reasons behind this swing cannot be known with

certainty, one likely explanation is that as Creative Commons

licences become more widely recognised by the general population and

are incorporated into more popular sites, such as the Flickr14

photo-sharing site, they are used by increasing numbers of amateur or

casual creators, who do not anticipate financial gains from their

creative output. Such users are more likely to allow broad use of

their material and to view re-use, including by professional

organisations, as complimentary rather than exploitative. An

anecdotal example of such a situation is provided by US-based

Creative Commons photographer Mike Kuniavsky, whose photograph was

used in January 2006 to illustrate an article in the Australian

Broadcasting Corporation’s (ABC) online arts review column,

Articulate, on a controversial advertising campaign for the

release of the Sony PlayStation Portable (PSP) gaming console.15

In his blog post on the subject, Mike comments favourably on the use,

stating:

For the new year, I was treated to an amusing honor. Australian ABC news used one of my Flickr pictures to illustrate a story on Sony's fake graffiti ad campaign. . . I think that the reason my picture was picked was because of its Creative Commons license. Woohoo! Go CC.16

Another possible explanation for the trend towards more liberal

Creative Commons licensing is that as creators become more familiar

with the licences, they are more comfortable allowing greater use of

their material. This suggestion is supported by anecdotal evidence

from Creative Commons licensors who, after initially publishing their

material under restrictive licences, ‘re-release’ their

material to allow greater re-use. The most famous example of such a

case is Cory Doctorow, science fiction author and co-editor of

popular blog Boing-Boing, who released his first novel, Down and

Out in the Magic Kingdom, in 2003 under an Attribution

Non-commercial No Derivative Works licence17

and re-released it a year later under the more permissive Attribution

Non-commercial Share Alike licence. In the blurb accompanying the

re-released novel, Doctorow states his reasons for re-licensing the

work:

When I originally licensed the book . . . I did so in the most conservative fashion possible, using CC's most restrictive license. I wanted to dip my toe in before taking a plunge. I wanted to see if the sky would fall: you see writers are routinely schooled by their peers that maximal copyright is the only thing that stands between us and penury, and so ingrained was this lesson in me that even though I had the intellectual intuition that a "some rights reserved" regime would serve me well, I still couldn't shake the atavistic fear that I was about to do something very foolish indeed.

It wasn't foolish. I've since released a short story collection (A Place So Foreign and Eight More [sic] and a second novel (Eastern Standard Tribe) in this fashion, and my career is turning over like a goddamned locomotive engine. I am thrilled beyond words (an extraordinary circumstance for a writer!) at the way that this has all worked out.

And so now

I'm going to take a little bit of a plunge. Today, in

coincidence with my talk at the O'Reilly Emerging Technology

Conference (Ebooks: Neither E, Nor Books) I am re-licensing this book

under a far less restrictive Creative Commons license, the

Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license. This is a license that

allows you, the reader, to noncommercially "remix" this

book -- you have my blessing to make your own translations, radio and

film adaptations, sequels, fan fiction, missing chapters, machine

remixes, you name it. A number of you assumed that you had my

blessing to do this in the first place, and I can't say that I've

been at all put out by the delightful and creative derivative works

created from this book, but now you have my explicit blessing, and I

hope you'll use it.18

3. Who is using the Licences, and why?

3.1 First generation users

The Creative Commons community is often typified as being made up of idealistic individuals, who are using the licences not for any practical purpose but because of a personal adherence to counter-culture or open source principles. As Kimberlee Weatherall points out in her 2006 article, Would you ever use a Creative Commons license?, this is often cited as a criticism of Creative Commons, with the licensing scheme being dismissed as “more social movement than pragmatic toolkit”19 utilised mainly by “hobbyists, academics, and other people who make their living by means other than selling creative outputs”.20 Such critics categorise the Creative Commons as little more than a “world-wide pool of clipart”.21

An informal survey of websites linked to the Creative Commons v1.0 licences shows that during its early days most of the initiative’s users can, indeed, be categorised as hobbyists and idealists. The initial application of Creative Commons was dominated by websites that discuss the open source22 and Creative Commons23 movements; websites of counter-culture advocates and political activists24; and weblogs, the medium of choice for ‘hobbyist’ culture25. Although exceptions to this rule do exist26 it is certainly true to say that many of the ‘first generation’ adopters of the Creative Commons licences were web-savvy users motivated, to varying degrees, by the free culture mantra that ‘information wants to be free’. This is hardly surprising – after all, during the early stages of the Creative Commons project it is unlikely that many people beyond this community had heard of open content licensing, or had any real understanding of copyright or the issues it presented in the digital environment – except, perhaps for a vague awareness of the Napster tale.27 The strong publicity and enforcement campaign by copyright owner organisations since this time has, of course, done much to educate the current population about copyright law.28

It is also true that so-called hobbyists and idealists still make up a significant portion of Creative Commons users. For example, at 1 January 2007 Flickr listed more than 26 million photos available under Creative Commons licences, the majority of which are home snapshots.29 And despite ongoing ideological debates, strong links still exist between Creative Commons and the open source community, with Linux Founder and open source guru, Linus Torvald, openly supporting the Creative Commons system30 and Creative Commons and the Free Software Foundation having jointly released the ‘CC-GNU GPL’.31 However, it is questionable whether the prevalence of hobbyist and ideology-motivated users is, in itself, a valid reason for criticising the Creative Commons movement. After all, a good portion, if not the majority, of the material available on the internet has been produced by private individuals working not for financial gain but for their own enjoyment. Indeed, ‘user generated content’ is the buzzword of the moment with sites such as Youtube32 and Myspace33, undoubtedly the internet success stories of 2006,34 building their business models around the productivity of amateurs. Meanwhile, Time magazine has dubbed 2006 “a story about community and collaboration on a scale never seen before” and voted You (ie amateur content generators) Person of the Year.35

These highly prolific home-creators are both the life-blood of the internet and the forgotten children of copyright regulation. The default copyright laws of most countries, with their ‘lock up the silverware’ approach, do not reflect the reality of a ‘cut and paste’ culture that relies on the ability to manipulate existing material for creation and whose principle measure of success is hits counted.36 With the possible exception of the US and its legally-controversial fair use right,37 few countries provide exceptions that allow private individuals to reproduce or manipulate copyright material purely for creative purposes, even where the use is transformative in nature. And while international copyright conventions provide a nod to the importance of amateur creators by requiring that protection be granted automatically, without the need for the registration and legal fees required by other forms of intellectual property,38 the sheer complexity and obtuseness of most countries’ copyright laws makes it impossible for the average individual to manage their rights in an effective manner without legal advice.

Australian law provides a good example of the failure of governments to take the needs of private individuals into account when developing copyright legislation. The vast majority of user exceptions in the Australian Copyright Act only provide rights to institutional users such as libraries, broadcasters and educational bodies.39 While these groups are worthy recipients of such rights, this does little to help those acting in the privacy of their own homes. Even the generic fair dealing exceptions, which ostensibly apply to the actions of private individuals, are structured around specific purposes such as ‘research and study’40, ‘criticism and review’41 and ‘reporting the news’42 which are arguably more likely to take place in the professional sphere (eg at a university, newspaper or radio station) than in the home. Although some of the owner rights provided by the Act, such as ‘public performance’43 and ‘communication to the public’44 are limited to acts that take place in the public arena there is no equivalent requirement for the primary right of reproduction. And even these so-called ‘public’ rights are so broadly defined as to encompass many ordinary acts of private individuals, such as emailing a home video with a commercial soundtrack to friends, or playing a CD in a public park.45 Until recently, the concept of ‘private’ copying only existed in the Australian Copyright Act in relation to an extremely narrow exception to permit the recording of broadcasts to watch at a more convenient time.46 The amendments introduced by the Copyright Amendment Act 2006, which came into effect between 11 December 2006 and 1 January 2007, go some way towards remedying this situation by introducing a number of exceptions specifically targeted at ‘private and domestic’ uses of copyright material.47 However, these exceptions are extremely limited in their scope and specifically tailored to permit only ordinary use of commercially available products such as video recorders and iPods.48 They do not permit the kind of ‘transformative uses’ that have been argued for by a number of user representative groups49 and are likely to do little for hobbyists and home-based creators.

Linked to the criticism that Creative Commons users are ‘mere hobbyists’ is a second criticism; that Creative Commons is of little utility to this group, as the materials that they are most likely to want to re-use - “corporate logos, Disney characters, and Barbie dolls”50 - are the least likely to be released under a Creative Commons licence. The implicit suggestion here seems to be that the ‘clip art’ produced by home-creators is of less value and interest to future artists than material created within the traditional corporate model. However, the validity of such as statement is highly questionable. As user generated content becomes more prolific the traditional boundary between popular culture and amateur productions is falling away. Unlike early file-sharing services such as Napster and Grokster, today’s popular content sharing sites such as Youtube, MySpace and Flickr are dominated by user-created content. This content has extremely high hit rates, with ‘amateur’ content regularly forming a good portion of the ‘most viewed’ categories of such sites.51 As Time notes, this phenomenon has become so wide spread that corporate entities are actively seeking to tap into the prolific creativity of the sharing culture - “car companies are running open design contests. Reuters is carrying blog postings alongside its regular news feed”.52 More importantly for the case in point, while there is certainly a swathe of derivative material, whether spoofs or tributes, based upon commercial products among this user-generated content, there is also a great deal of imitation of, commentary on and interaction with other user-generated content.53 To creators of the 2006 generation, Mickey Mouse is no longer the pinnacle of cultural expression.

Furthermore, despite their understandable reluctance, large producers of mass-market copyright material are gradually opening up access to their catalogues. While ‘old school’ rights management tools such as the Content Scramble System used on DVDs prohibit all copying of material, licences on download sites such as iTunes permit limited reproductions, allowing users to make ‘reasonable’ uses of the material they have paid for.54 It seems only a matter of time before these licences are extended to allow more transformative uses. Indeed, over the last few months agreements that allow not only the reproduction of corporate material but its inclusion in new works (eg as a soundtrack to an amateur video) have been negotiated between YouTube and a number of prominent corporate copyright owners, including record labels Sony BMG55 and Universal Music Group56, with the copyright owners receiving a share of the advertising revenue generated by the new content in return. These developments seem to indicate an acknowledgement by the corporate world that benefits can be gained by providing at least some freedom for ordinary users to share and even manipulate copyright material, within clearly defined boundaries.

3.2 Second generation users

As the above discussion shows, arguments that purport to criticise Creative Commons purely on the basis that it is a movement of clip art can themselves be criticised as undervaluing the importance of user-generated content in the digital era, and the resource this can provide for further creation. However, on a more pragmatic level, they can also be seen to be an inaccurate depiction of the Creative Commons user base five years down the track. While it is true that individuals, including hobbyists and academics, still make up a large portion of Creative Commons licensors, an increasing number of ‘second generation’ users are emerging in the form of non-profit institutions, government bodies and even commercial entities who are choosing, for a range of reasons, to incorporate the Creative Commons licences into their business models.

Services that build upon the Creative Commons model have, of course, existed since the licences were first released in 2002. A perfect example of this is music site ccMixter57, which was launched in November 2004 and provides both a platform for people to share Creative Commons music and the tools to remix that material.58 However, ccMixter and similar open content sites such as the Sciencecommons59, Opsound60 and Jamendo61 cannot truly be said to provide evidence of Creative Common’s utility for ‘real-world’ businesses, as they are essentially ‘CC spinoffs’ – non-profit services that have grown out of the Creative Commons and open source movements and which do not have any independent business considerations or aims beyond encouraging collaboration and innovation in the digital environment.

Yet such ideology-based organisations are no longer the only bodies making use of Creative Commons licensing. An increasing number of independent companies and institutions are now choosing to utilise Creative Commons and other open content licensing models – not because of any conscious affiliation with these movements but simply because the legal framework they provide suits the organisation’s purposes. These bodies include both commercial businesses and ‘professional’ non-profit and public sector organisations (ie organisations that do not operate for a profit but which provide access to material that has been produced as part of a public enterprise, on a large scale and usually with government or corporate funding). This increase in use by independent businesses and organisations is important for Creative Commons, as it provides evidence of the utility of its system for such organisations, and the benefits open content licensing can provide beyond the standard ideological arguments.

Although many of these second generation users do have some ideological basis for utilising open content licensing, they differ from the Creative Commons affiliate organisations discussed above in that this ideology is not their only reason for existing. For example, many government institutions such as libraries and public broadcasters may utilise Creative Commons licensing as part of a policy to increase access to certain sections of their collection for public benefit reasons, but would not apply the same generic sharing principles to all content in their possession. Furthermore, as public institutions they must take greater account of traditional ‘business’ considerations such as cost and accountability before they choose to deploy the licences. Similarly, while commercial services like Flickr and music publisher Magnatune62 (discussed below) are part of the growing movement of new ‘open’ media outlets aiming to provide greater options for creators and users alike, they do this not merely because of an underlying ethical argument, but because it enhances their commercial activities by enabling them to access hitherto untapped markets and business models. They adopt Creative Commons because it provides the best legal model they can find to achieve the business ends they desired.

3.3.1 Non-profit and public sector users

Non-profit and public sector initiatives make up one of the largest groups of Creative Commons and open content licensing institutional users. These initiatives may take the form of publishing projects by governments themselves, such as the Brazilian government’s formal adoption of the CC-GPL licence for the release of all its software;63 schemes by government-funded institutions, such as the UK’s Creative Archive Group64 of which the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) is the most prominent member; or programs of non-profit educational institutions, such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s (MIT) OpenCourseWare (OCW) project65. The motivations of such bodies for adopting open content licensing generally have a strong public policy basis, and are well summarised by the follow statements released at the launch of the Creative Archive Group:

The Creative Archive Licence scheme aims to

Pioneer a new, more refined approach to rights management in the digital age

Encourage the establishment of a public domain of audio-visual material

Help stimulate the growth of the creative economy in the UK

Establish a model for others in the industry and public sector to follow

Exemplify a new open relationship between the four partners in the pilot schemes and other industry players

Mark Thompson, Director General of the BBC, said: “The Creative Archive Licence provides a unique solution to one of the key challenges of rights in the digital age, allowing us to increase the public value of our archives by giving people the chance to use video and audio material for their own non-commercial purposes. All four partners in the Creative Archive Licence Group feel this is a fantastic opportunity for other broadcasters and rights holders, and we would urge them to join us.”66

However, these projects are differentiated from community-based

‘ideological’ services such as ccMixter by their location

within ‘traditional’ bodies, which have large financial

and content resources at their disposal and which have entrenched

‘closed’ copyright management policies and business

models that have been in existence since long before the internet

revolution. This requires them to consider in greater detail the

practical, legal and financial advantages and disadvantages of open

content licensing. The fact that they have nonetheless chosen to

employ such licensing would seem to suggest that they have decided

that, on the balance of probabilities, the benefits it can provide

them outweigh the risks.

This conclusion is supported by the findings of a study undertaken by

Intrallect and the University of Edinburgh’s AHRC Research

Centre for Studies in Intellectual Property and Technology Law, for

the Common Information Environment (CIE) group, a collection of

significant public sector stakeholders from the UK, including the

British Library, the UK e-Science Core Programme, the Joint

Information Systems Committee (JISC), the Museums, Libraries and

Archives Council (MLA) and the NHS National Electronic Library for

Health (NeLH). The 2005 study, entitled The Common Information

Environment and Creative Commons, was commissioned by CIE to

investigate the potential for Creative Commons licences to be used by

its members to clarify and simplify the process of making digital

resources available for re-use. As well as the general benefits they

provided in terms of maximising the use and reuse of resources

primarily funded by UK tax payers and promoting a culture of openness

and freedom of information, the report found that Creative Commons

licensing could provide the following specific benefits for public

sector organisations:

Consistent and transparent treatment of digital resources

Improved perception of “value for money”

Reduction in effort of dealing with enquiries for information/resources

Reduction in effort of developing a reuse policy by sharing a common policy

Reduction in legal input required through adoption of existing licences rather than drafting new and varied licences in each organisation/group/project

Enhanced PR, potentially leading to increased use of other services

Choice of licences offers flexibility

A framework for rights clearance conditions in future projects67

The practical benefits a non-profit or public sector body may obtain from open content licensing are well demonstrated by the OCW project provides. This project, launched by MIT in 2002, makes the course materials from virtually all of the university’s undergraduate and graduate courses available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share-Alike licence. In a 2004 report on the project’s progress Steven Lerman, then chair of the OCW Faculty Advisory Committee, listed the following reasons for the body’s adoption of Creative Commons licensing:

OCW is a 'two-fer:' it helps faculty organize their course materials, and it helps us communicate with each other. I can see how prerequisites I listed are taught. It's also a way to further MIT's mission; embrace faculty values of teaching, sharing best practices and contributing to our fields. Beyond that, OCW counters the privatization of knowledge; it champions openness.68

As this statement indicates, while ideological motivations relating

to the ‘openness’ of knowledge certainly featured in

MIT’s decision, more practical benefits relating to the quality

and efficiency of MIT’s teaching services also played a

significant role. This surmise is further supported by the OCW 2005

Program Evaluation Findings Report, which found that the

initiative had had the following impacts:

8.5 million visits were made to OCW content in 2004, 61% from outside the United States;

71% of MIT students, 59% of faculty members and 42% of alumni use the OCW site;

OCW materials are widely distributed to secondary audiences, with 18% of visitors distributing offline copies to others;

75% of MIT’s faculty had published courses on OCW; of these, 32% agreed that publishing their teaching materials on OCW improved them;

Educators re-used OCW in the following ways:

46% had adopted or adapted site content;

92% planned to in the future;

62% combined OCW materials with other content;

96% said the site had/will help improve courses.

69% of MIT students said OCW has positively impacted student experience;

the project had had a significant influence on prospective students, with 35% of freshmen aware of OCW before deciding to attend MIT being influenced by it; and

80% of visitors rated OCW’s impact as extremely positive or positive; 91% expected that level of future impact.69

An Australian initiative that provides another example of both the ideological and practical considerations that can motivate a public sector institution to take up open content licensing is the National Library of Australia’s (NLA) Click and Flick project. Launched in January 2006, Click and Flick is a project of the NLA’s online pictorial gateway, PictureAustralia70, in partnership with the Flickr photosharing website. PictureAustralia is an internet portal that allows users to search over 1.1 million images from 45 organisations across Australia and New Zealand simultaneously.71 Although it does not act strictly as an archive, in that it does not house any of the images but merely provides links to images stored by other bodies, it aims to create the experience of a unified collection accessible through a single search engine.

The Click and Flick initiative was launched as a way of increasing the number of contemporary images available through PictureAustralia. It provides an opportunity for individuals to contribute their own images to the national collection simply by uploading them onto Flickr. Working in conjunction with Flickr enables PictureAustralia to tap into the public-profile and popularity of the photo-album website, as well as its established publication tools. Once the contributor has uploaded their photo via the standard Flickr process they need merely tag it as being part of one of the dedicated PictureAustralia groups to donate it to the collection.72 The NLA’s search engine can then access the photograph in the same manner as it does those of the other archives participating in PictureAustralia.

The original PictureAustralia groups, 'Australia Day' and 'People, Places and Events', encouraged users to use Creative Commons licensing for their photographs, but did not make it mandatory.73 However, after a year’s experience with optional content licensing, the NLA closed the less popular 'Australia Day' group, and launched a new 'Ourtown' group. For this group they decided to make Creative Commons licensing compulsory, including the following statement on its home page:

It is a condition of contribution to this group, that your images be licensed with a Creative Commons like “Attribution-NonCommercial”. This allows PictureAustralia, to: exhibit your work for non commercial purposes promoting the project on the Library’s premises and elsewhere, to reproduce the work for publications and publicity and to lend it to other parties for exhibition providing the creator is attributed.74

As with the other public sector users discussed, it seems likely that there is a strong ideological motivation behind this support for Creative Commons licensing – PictureAustralia is, after all, part of the national collection and, from the point of view of a librarian, the more freely accessible the photographs the better. In an interview conducted by the author and published in the program of the iCommons iSummit 200675, Fiona Hooton, manager of PictureAustralia, indicated that the NLA had decided to promote Creative Commons licensing because it “encourages content contributors to think in terms of a librarian keeping in mind the public benefit of providing maximum access to content as part of Australia’s national collection”.76 In the same interview, Ms Hooton also indicated that the NLA’s decision to use Creative Commons licensing was in part motivated by the benefits open content licensing provides for the users of PictureAustralia. Because of the prohibitive cost of obtaining copyright clearances for such a large pool of material, most of the photographs available through PictureAustralia are listed as ‘all rights reserved’. Although a number of the participating institutions have general policies permitting ‘private and domestic’ use of their images, for many pictures in the collection permission for reproductions must be sought from the owner-institution. By requiring creators who upload their own photographs through Flickr to open license their material from the outset, the NLA is hoping to “develop a pool of Creative Commons licenced [sic] images which can be generally used without needing to seek additional permission”.77

However, the NLA did not choose to use Creative Commons licensing purely because of the public interest benefits it provided. As the statement extracted from the home page of the Ourtown group above indicates, the NLA also obtains more utilitarian benefits in terms of content management from the open licensing of photos donated to their collection. One of the biggest obstacles to increased access to library materials in the digital age is the difficulty of obtaining the copyright clearances required to manipulate and maintain a digital collection. This is a particular problem for those works where the author may be difficult or impossible to locate – as is generally the case with photographs, which will often be donated by members of the public with little accompanying information. Although the Australian Copyright Act grants libraries certain rights to reproduce and communicate material held in their collection for administrative and preservation purposes,78 currently these rights are limited to very specific circumstances and do not cover a broad range of activities routinely undertaken by libraries, such as making a photograph available online, making multiple preservation copies, working with volunteers, running exhibitions and producing catalogues and promotional materials.79

By obtaining the work under a Creative Commons licence, the NLA is able to overcome this difficulty, ensuring that they have the rights they need to deal efficiently and effectively with the image, and that they will retain these rights for the full duration of copyright. Furthermore, because the Creative Commons licences are worded to essentially grant full usage rights, subject only to the restrictions prescribed by the licence elements and certain licence-specific limits,80 the NLA can have reasonable confidence that they will be sufficiently broad to allow future uses that may not be encompassed by more specific copyright licences. This will hopefully enable them to avoid the situation that many newspapers, for example, found themselves in with the birth of the internet, where their existing licences did not permit them to republish past editions online without additional permissions.81 At the same time, by using the Creative Commons licences the NLA is still able to provide creators with some choice over how their material may be used in the future, rather than imposing a standard terms of use agreement on all contributors, as would usually be the case for such a large-scale donation scheme. In fact, in the iCommons interview, Ms Hooton indicated that the use of Creative Commons licensing for the collection was first suggested by the site’s web manager “as a good way of ensuring the library had the rights they needed to harvest, maintain and promote the collection, while still allowing the individual to retain control over their image”.82

Click and Flick has turned out to be highly successful for the NLA, with over 13,000 photographs uploaded during its first 12 months.83 While this figure is only small compared to the more than 300,000,000 photographs available on Flickr84, it is an extremely successful collection process for an Australian library initiative. The project has also significantly raised the profile of the PictureAustralia collection, with the NLA reporting much higher usage, even during traditionally slow periods, and has garnered considerable attention among the international library community.85

3.2.1 Commercial services

While public sector users have clear ideological and practical reasons for utilising Creative Commons licensing, the second generation institutional users are not limited to such ‘public minded’ bodies. The group also includes a number of purely commercial organisations which are utilising Creative Commons as part of their broader business model. Some of these services, such as Flickr, have incorporated Creative Commons licences into their systems simply as a way of increasing the utility and flexibility of their site for contributors and users, without any disadvantage to their company’s own systems or business models. Such sites can be classified as Creative Commons supporters, as they recognise Creative Commons as a legitimate option that their creator users may wish to utilise; however, their business models are in no way reliant on Creative Commons licensing and they cannot truly be said to provide evidence of the commercial utility of Creative Commons. Yet a small but significant group of commercial entities are starting to emerge that do incorporate Creative Commons licensing as a fundamental part of their business strategy. These businesses provide services that aim to take better advantage of the fundraising potential of the internet, digital technologies and user-creator culture by tapping into trends that are as-yet underutilised and even demonised by traditional media.

For example, music download site Magnatune, founded in 2003, aims to take advantage of the sharing mentality of the online community to reach niche markets are not serviced by the traditional record industry. It does so by providing a variety of ‘free trial’ mechanisms for the independent music available on its site, including 128kb MP3s. These MP3 previews are available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-ShareAlike licence, allowing people to promote the music to others or even remix it into their own new work. If users like what they hear, they can pay US$5-18 to download a higher-quality version of the entire album, with all proceeds split 50/50 between Magnatune and the artist. The music can also be licensed for commercial use (eg in an advertisement or re-mix CD) through direct negotiation with Magnatune.

Magnatune sets out its basic ethos on the ‘Big Ideas’ page of its website as follows:

All music should be shareware. Just as with software, you want to preview, evaluate, and pass along good music to others--in the process of buying it.

Find a way of getting music from the musician to their audience that's inexpensive and supports musicians. Otherwise, musical diversity will continue to greatly suffer under the current system where only mega-hits make money.

Musicians need to be in control and enjoy the process of having their music released. The systematic destruction of musician's lives is unacceptable: musicians are very close to staging a revolution (and some already have).

Creativity needs to be encouraged: today's copyright system of "all rights reserved" is too strict. We support the Creative Commons "some rights reserved" system, which allows derivative works, sampling and no-cost non-commercial use.86

This statement clearly indicates that Magnatune has a strong ideological motivation for using open content licensing. However, it links this ideology to the practical and financial benefits which can be gained by tapping into the distribution potential of the internet, both as a tool for encouraging diversity and as a way of lowering the costs of publication and promotion to enable musicians to retain greater control over their material. As Magnatune’s tiered distribution and payment model demonstrates, it does not believe that music should simply be given away for free; however, it does believe that in the online environment providing free ‘samples’ is the best and simplest means of promoting its artists to encourage greater purchasing and commercial licensing of their material.

Magnatune uses Creative Commons as a promotional tool to support its traditional sales and licensing models. Open content licensing is therefore advantageous for Magnatune’s business model, but it is arguably not essential to it. However, new business Revver87 goes one step further by tying its revenue raising mechanism directly to the Creative Commons licensing it uses. Revver is a free video sharing site, similar to the popular Youtube. However, unlike Youtube, Revver is specifically designed to take advantage of the popularity of sharing free videos via mechanisms such as email and peer-to-peer to provide a revenue-raising model for creators. Rather than merely displaying ads in conjunction with videos (Youtube's current revenue-raising model), Revver uses proprietary software to embed advertising directly into the video itself. Once this is done, the video can be downloaded and shared via any method – website, email, even peer-to-peer – without ‘losing’ the advertisement. The Revver software reports back to the main website each time the video is viewed, and the advertiser is charged a micro-payment. These payments are split 50-50 between Revver and the video's creator.

Revver's business model is particularly interesting because it aims to take the wide-spread sharing of copyright material that occurs online and turn it into an asset, rather than a reason for litigation. Revver's revenue-raising strategy not only permits widespread distribution, it relies on it – the more people who see the video, the more money both the site and the creator earns. As the About section of the Revver website puts it:

Revver is... a video-sharing platform built upon how the internet really works. There is no stopping online media sharing. Why would you want to? Revver's model is one of free and unlimited sharing. Our unique technology tracks and monetizes videos on our network as they spread virally across the web.

It therefore makes sense that, as part of this business model, Revver requires that all people make their material available under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-NoDerivatives licence. Creative Commons licences are, after all, specifically designed to maximise the ability of users to distribute material in the online environment. The licence chosen by Revver is particularly well suited to this, as it encourages distribution of the material whilst limiting its alteration or re-use for the revenue raising purposes of third parties.

The Revver service has only existed in beta form since early 2006, and as such is still in its fledgling stages. However, even before its 1.0 version was launched in September 2006, it already had a success story in the ‘Extreme diet coke and mentos experiment’ video.88 This video, which was produced by performance-artists Eepybird, features two lab-coat clad performers creating a four minute, coordinated fountain display using only diet coke and mentos. As of July 2006, its ‘Revverised’ version had been viewed more than 6 million times, and had reportedly earned over US$28,000 in revenue.89 In the wake of this success, Revver has begun to attract a number of other popular professional online videos, including the ‘AskaNinja’90 and ‘lonelygirl15’91 franchises, and in early November 2006 was nominated by The National Television Academy for the ‘Outstanding Innovation and Achievement in Advanced Media Technology for the Best Use of “On Demand” Technology Over the Public (open) Internet’ category of their Emmy awards.92 In the same week, Revver won the US magazine TV Week’s Viral Video Award for Most Influential Website.93 The very existence of these awards shows that traditional media is beginning to adapt to the new world of sharing and re-use of digital material. This acceptance is led by innovative businesses such as Revver, which embrace this world rather than resisting it, and demonstrate that Creative Commons can have a legitimate place in commercial enterprise.

4. Conclusion

While there is only limited statistical evidence currently available about Creative Commons licence use, based on general observations and anecdotal evidence it is possible to see trends emerging in how and why individuals and institutions alike are choosing to make their copyright material available under the open content licensing system. Creative Commons provides a valuable resource for the modern ‘cut and paste’ culture that has been neglected by traditional copyright law. The need for content management tools that are both easy to use and free, and material that can be legally utilised by private individuals for creative purposes without the need to obtain additional permissions, will only increase as user-generated content grows in importance and popularity. Those who seek to criticise Creative Commons on the basis that it meets this need are under-estimating the value of home-creators and re-mix culture in 2006. Furthermore, they are ignoring the reality of Creative Commons use today, and the growing evidence that open content licensing can be utilised to advantage by large-scale content producers and commercial businesses alike. Five years down the track, increasing numbers of public-sector organisations are choosing to make use of Creative Commons to open up access to their materials and assist with their own internal rights management processes. At the same time commercial services are emerging which, while in their fledgling stages, are exploring possibilities for tapping into the sharing-culture of the internet to provide direct financial benefits to individual creators. While such alternative funding models are unlikely to replace the traditional corporate models that have brought us mass-media and Hollywood blockbusters any time soon, they do provide a workable model for those creators who want to take better advantage of the opportunities that the internet provides.

* Project Manager, Creative Commons Clinic, Queensland University of Technology

1 The Creative Commons grew primarily from concepts set out in Lawrence Lessig’s The Future of Ideas: The Fate of the Commons in a Connected World (Random House, 2001). For a full discussion of the principles and basis of the Creative Commons movement, see Lawrence Lessig, Free Culture: the Nature and Future of Creativity (Penguin Books, 2004) 282-86 and ‘About Us’, Creative Commons <http://creativecommons.org/about/history> at 1 January 2007

2 For a full discussion of the links between free culture, Creative Commons and the open source software movement see Brian Fitzgerald and Ian Oi, ‘Free Culture: cultivating the Creative Commons (2004) 9 Media & Arts Law Review 137 at 138

3 Lawrence Lessig, Free Culture: the Nature and Future of Creativity (Penguin Books, 2004) 285

4 Mia Garlick, ‘Version 3.0 - Launched’ (2007) Creative Commons <http://creativecommons.org/weblog/entry/7249> at 14 March 2007

5 For the full details of the licence elements see ‘Choosing a license’ Creative Commons <http://creativecommons.org/about/licenses> at 20 December 2006

6 Creative Commons also provides more specialised licences, such as the Public Domain licence <http://creativecommons.org/license/publicdomain-2>, which dedicates the work to the public domain, and the Sampling Licences <http://creativecommons.org/about/sampling>, which allow portions of a work, but not the whole, to be remixed. However, these licences are far less commonly used than the core licences, and will not be dealt with in detail in this paper.

7 See, ‘Choose a license’ Creative Commons <http://creativecommons.org/license/> at 20 December 2006. The licence generator is also available as a desktop wizard <http://wiki.creativecommons.org/CcPublisher> and as a Microsoft Office plugin <http://www.microsoft.com/downloads/details.htmlx?FamilyId=113B53DD-1CC0-4FBE-9E1D-B91D07C76504&displaylang=en>

8 See, for example, ‘CC Search’ Creative Commons <http://search.creativecommons.org/> at 20 December 2006

9 Figures based on Yahoo! queries. See ‘License Statistics’ (2006) Creative Commons <http://wiki.creativecommons.org/License_statistics> at 20 December 2006

10 ‘License Statistics’ (2006) Creative Commons <http://wiki.creativecommons.org/License_statistics> at 20 December 2006

11 Note that in those jurisdictions that recognise moral rights the Creative Commons licences will usually explicitly reserve these rights, giving authors the right to object to derogatory treatment of their work even under those licences that permit derivative works. See, for example, clause 4(d) of the Australian Creative Commons Attribution licence v2.5 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/au/legalcode> at 20 December 2006.

12 ‘License Statistics’ (2006) Creative Commons <http://wiki.creativecommons.org/License_statistics> at 20 December 2006

13 Based on figures available at Mike Linksvayer, ‘License adoption estimates’ (2005) Creative Commons <http://creativecommons.org/weblog/entry/5861> at 20 December 2006 and ‘License Statistics’, Creative Commons <http://wiki.creativecommons.org/License_statistics> at 20 December 2006

15 Matt Liddy, ‘Sony’s Stealth Ads Backfire’, Articulate <www.abc.net.au/news/arts/articulate/200601/s1541519.htm> at 20 December 2006

16 Mike Kuniavsky, ‘Creative Commons works, astroturfing doesn't’ (2006) Orange Cone <http://www.orangecone.com/archives/2006/01/creative_common.html> at 20 December 2006. Interestingly, a user response, unverified but claiming to be from the article’s author, Matt Liddy, states “And yes, the CC licence was definitely part of the reason I used your photo. The traditional picture agencies we use didn't have any photos of the PSP ads, so Flickr and CC was a handy alternative”

17 Cory Doctorow, ‘Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom’ (2004) Craphound <http://www.craphound.com/down/> at 20 December 2006 The statement explaining the book’s licensing and Doctorow’s reasons for using Creative Commons licences can be found at Cory Doctorow, ‘Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom – a note about this book’ (2003) Craphound http://www.craphound.com/down/Cory_Doctorow_-_Down_and_Out_in_the_Magic_Kingdom.htm#about at 20 December 2006

18 The statement explaining Doctorow’s decision to release the book under the Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike licence can be found at Cory Doctorow, ‘Down and Out in the Magic Kingdom – a note about this book’ (2004) Craphound <http://www.craphound.com/down/Cory_Doctorow_-_Down_and_Out_in_the_Magic_Kingdom.htm#aboutnew> at 20 December 2006

19 Kimberlee Weatherall, ‘Would you ever recommend a Creative Commons license’ [2006] Australasian Intellectual Property Law Resources 4 at 2, available at <http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/other/AIPLRes/2006/4.html> at 20 December 2006

20 Ibid.

21 Ian MacDonald, ‘Creative Commons licences for visual artists: a good idea?’ (2006) Australian Copyright Council <http://www.copyright.org.au/pdf/acc/articles_pdf/a06n04.htm/ > at 5 December 2006

22 See, for example Open Source Articles <http://opensourcearticles.com/> at 21 December 2006 and Peter Suber, Open Access News <http://www.earlham.edu/~peters/fos/2005_01_09_fosblogarchive.html> at 21 December 2006

23 See, for example, Common Content <http://commoncontent.org> at 21 December 2006

24 See, for example, The Yes Men <http://www.theyesmen.org/> at 21 December 2006

25 See, for example, BlogLatin < http://www.webamused.com/bloglatin/> at 21 December 2006; Suburban Blight <http://www.suburbanblight.net/> at 21 December 2006; Family Medicine Notes <http://www.docnotes.net/> at 21 December 2006. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the most common category of site connected to the early Creative Commons licences appears to be a weblog by an advocate of the free culture movement - see, for example, Jason Shultz, LawGeek <http://lawgeek.typepad.com/lawgeek/> at 21 December 2006; Simon Collison, Collylogic <http://www.collylogic.com/> at 21 December 2006

26 See, for example, pizza review site Slice <http://www.sliceny.com/> at 21 December 2006

27 For a summary of the litigation surrounding the Napster peer-to-peer network see ‘Napster Cases’, Electronic Frontiers Foundation <http://www.eff.org/IP/P2P/Napster/> at 21 December 2006

28 For a summary of the music industry’s piracy litigation and education strategy, see Oleg V Pavlov, ‘Dynamic Analysis of an Institutional Conflict: Copyright Owners Against Online File Sharing’ (2005) Journal of Economic Issues, Vol. 39, No. 3, at 633-663.

29 ‘Creative Commons’ (2007) Flickr <http://www.flickr.com/creativecommons> at 1 January 2007

30 Stephen Shankland ‘Torvalds says DRM isn't necessarily bad’, CNet News.com (3 February 2006) <http://news.com.com/Torvalds+says+DRM+isnt+necessarily+bad/2100-7344_3-6034964.html> at 14 March 2007. Although it should also be noted that many of the strongest critics of the Creative Commons movement are open source advocates who disagree with Creative Commons use of licensing restrictions such as Non-commercial and No Derivative Works. See, for example, comments by Richard Stallman, President of the Free Software Foundation at ‘Fireworks in Montreal’ (2005) Free Software Foundation <http://www.fsf.org/blogs/rms/entry-20050920.html> at 21 December 2006. In fact, the Free Software Foundation does not itself currently recommend the use of Creative Commons licensing, due to its concern over the variability in the licence terms - see ‘Various licences and comments about them’ (2006) Free Software Foundation <http://www.fsf.org/licensing/licenses/> at 21 December 2006.

31 ‘Creative Commons GNU GPL’, Creative Commons <http://creativecommons.org/license/cc-gpl> at 21 December 2006. While not a Creative Commons licence itself, adds the Creative Commons' metadata and Commons Deed to the Free Software Foundation's GNU General Public Licence.

34 Articles discussing the 2006 success of Youtube and MySpaces can be found at Tom Krazits, ‘Google makes video play’ News.com (9 October 2006) <http://news.com.com/Google+makes+video+play+with+YouTube+buy/2100-1030_3-6124094.html> at 21 December 2006; Matt Krantz, ‘The guys behind Myspace.com’ USA Today (12 February 2006) <http://www.usatoday.com/money/companies/management/2006-02-12-myspace-usat_x.htm> at 21 December 2006; and Paul Boutin, ‘A Grand Unified Theory of Youtube and Myspace’ Slate (28 April 2006) <http://www.slate.com/id/2140635/> at 21 December 2006

35 Lev Grosman, ‘Time’s Person of the Year: You’ Time.com (13 December 2006) <http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1569514,00.html?aid=434&from=o&to=http%3A//www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0%2C9171%2C1569514%2C00.html> at 21 December 2006

36 For discussion on the importance of the ability to reproduce existing material as part of freedom of expression in modern culture, see Chapter 2 of Lawrence Lessig, Free Culture: how big media uses technology and the law to lock down culture and control creativity (Penguin Press, 2004) at 31.

37 For discussion of the application of the US fair use doctrine to private actions see Siva Vaidhyanathan, Copyrights and Copywrongs: The Rise of Intellectual Property and How It Threatens Creativity (NYU Press, 2003). For discussion of the doctrine’s compliance with international copyright law see Tami Dower, ‘Casting the Fair Net Further: Should Australia Adopt an Open-ended Model of Fair Dealing in Copyright?’ (2002) 20(1) CopyReptr 4

38 See, for example, the Berne Convention for the Protection of Literary and Artistic Works opened for signature 9 September 1886 Art 5 available at <http://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ip/berne/trtdocs_wo001.html> at 21 December 2006

39 See for example Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) ss 47-47AA, 48A-52, 107, 109, 110A-110C, Part VA and Part VB

40 Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) s40

41 Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) s41

42 Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) s42

43 Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) s31(1)(a)(iii)

44 Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) s31(1)(a)(iv)

45 For a discussion of the scope of the definition of ‘to the public’ in relation to the communications and performance rights under Australian copyright law see J Lahore and W Rothnie Copyright and Designs (Butterworths, 1996) 34,031 and 34.435-34,455

46Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) s111

47 See, for example, Copyright Amendment Act 2006 (Cth) Schedule 6, Parts 1 and 2.

48 As evidenced by the emphasis placed on ensuring “consumers will no longer be breaching the law when they record their favourite TV program or copy CDs they own into a different format” in the Second Reading Speech presented by the Attorney-General, the Hon Phillip Ruddock MP – Commonwealth Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 19 October 2006 (Phillip Ruddock, Attorney-General) available at <http://parlinfoweb.aph.gov.au/piweb//view_document.htmlx?TABLE=HANSARDR&ID=2640061>

49 See, for example, the submission of the Australian Libraries Copyright Committee to the Senate Committee on Legal and Constitutional Affairs Inquiry into Provisions of the Copyright Amendment Bill 2006, available at ‘Australian Libraries Copyright Committee’ (2006) Parliament of Australia Senate <http://www.aph.gov.au/Senate/committee/legcon_ctte/copyright06/submissions/sub51.pdf> at 1 January 2007.

50 Ian MacDonald, ‘Creative Commons licences for visual artists: a good idea?’ (2006) Australian Copyright Council <http://www.copyright.org.au/pdf/acc/articles_pdf/a06n04.htm/> at 5 December 2006

51 For example, on 6 December 2006 the ‘Most Viewed’ page of Youtube included the following user-generated videos: wiz261 ‘We Met on MySpace: Episode 6’ (2006) Youtube <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o0xpSHppYug> at 6 December 2006; LVEFilms ‘Tinker and Tater's Whoop A$$ POtC Review’ (2006) Youtube <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=10tKUSq-zC4> at 6 December 2006; and OpAphid, ‘Home Alone’ (2006) Youtube <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QtxH6ScrZeY> at 6 December 2006.

52 Lev Grossman, ‘Time’s Person of the Year: You’ Time (13 December 2006) http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1569514,00.html?aid=434&from=o&to=http%3A//www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0%2C9171%2C1569514%2C00.html at 1 January 2007

53 See, for example, the following videos drawing on the popular Youtube vlogger Geriatric1927: newl, ‘Geriatric1927’ (2006) Youtube <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VtwX5wF7rWU> at 1 January 2007; jsic, ‘Geriatric1927’ Youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VtwX5wF7rWU> at 1 January 2007; elminer, ‘Geriatric1927 new’ (2006) Youtube < http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=R6paKUBmZIk&mode=related&search=> at 1 January 2007.

54 For a summary of the iTunes licensing terms, and those of other prominent music download services, see Appendix A of Deirdre K. Mulligan, John Han and Aaron J. Burstein ‘How DRM-Based Content Delivery Systems Disrupt Expectations of “Personal Use”’ (2003) University of California Berkeley, School of Law Boalt Hall <http://www.law.berkeley.edu/clinics/samuelson/projects_papers/WPES-RFID-p029-mulligan.pdf> at 1 January 2007

55 See Youtube ‘Sony BMG Music Entertainment Signs Content License Agreement with YouTube’ (Press Release, 9 October 2006) available at <http://www.youtube.com/press_room_entry?entry=2cwCau7cKsA> at 1 January 2007

56 See Youtube ‘Universal Music Group and YouTube Forge Strategic Partnership’ (9 October 2006) available at <http://www.youtube.com/press_room_entry?entry=JrYdNx45e-0> at 1 January 2007

58 See ‘Frequently Asked Questions’ ccMixter <http://ccmixter.org/media/viewfile/isitlegal.xml> at 1 January 2007

63 Creative Commons, ‘Brazilian Government First to Adopt New “CC-GPL”’ (Press Release, 2 December 2003) available at <http://creativecommons.org/press-releases/entry/3919> at 1 January 2007

64 <http://creativearchive.bbc.co.uk> Due to licensing and funding considerations, the Creative Archive Group does not use a Creative Commons licence per se. However, it does make its material available under an open-content licence modelled closely on the CC model. The Licence FAQ section of the Creative Archive website <http://creativearchive.bbc.co.uk/archives/what_is_the_licence/licence_faqs/> explains its position in relation to Creative Commons as follows:

The Creative Archive Licence is heavily inspired by the Creative Commons Licences. However, public service organisations within the UK have additional requirements that need to be reflected in the terms under which they licence content. The two most obvious of these are the UK-only requirement and the No Endorsement requirement. In addition, the Creative Archive Licence seeks to protect the Licensor's moral right of integrity, that is, the right not to have a work treated in a derogatory or objectionable way.

66 Creative Archive Licence Group, ‘Creative Archive Licence Group launches’ (Press Release, 13 April 2005) <http://creativearchive.bbc.co.uk/news/archives/2005/04/pr_creative_arc.html> at 1 January 2007

67 ‘The Common Information Environment and Creative Commons: Final Report to the Common Information Environment Members of a study on the applicability of Creative Commons Licences’ (2005) Intrallect <http://www.intrallect.com/cie-study/CIE_CC_Final_Report.pdf> p32

68 Sarah H Wright, ‘OCW Report Extols Progress’ (Press Release, 2 September 2004) <http://web.mit.edu/newsoffice/2004/ocw-0922.html> at 1 January 2007

69 2005 Program Evaluation Findings Report, MIT Opencourseware (Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2006) 2-4 available at <http://ocw.mit.edu/NR/rdonlyres/FA49E066-B838-4985-B548-F85C40B538B8/0/05_Prog_Eval_Report_Final.pdf> at 1 January 2007

71 For more information see ‘About Us’ Picture Australia <http://www.pictureaustralia.gov.au/about.html> at 1 January 2007

72 Click and Flick initially began with two groups: ‘Australia Day’ and ‘People, places and events’. However, in November 2006 the NLA subsumed the small ‘Australia Day’ group into the more popular ‘People, places and events’. A new group titled ‘Our Town’ is scheduled to be launched in early 2007.

73 The following statement included on the homepage of each of the Flickr groups: 'While this is not a condition for contributing to this group, we suggest you consider licensing your images with a Creative Commons [sic] like “Attribution-NonCommercial”, as this assists us when promoting the initiative.' - ‘PictureAustralia: People Places and Events’ (2006) Flickr <http://www.flickr.com/groups/pictureaustralia_ppe/> at 1 January 2007

74 ‘Ourtown’ (2006) Flickr <http://www.flickr.com/groups/pictureaustralia_ppe/> at 10 March 2007

75 Interview with Fiona Hooton, Manager, PictureAustralia (Brisbane-Canberra teleconference, 26 May 2006) published as ‘PictureAustralia’ iSummit ’06 (iCommons Ltd, 2006) 22-23. For more information on the iSummit, see ‘iSummit ’06 Coverage’ (2006) iCommons <http://www.icommons.org/isummit/index.php> at 1 January 2007

76 ‘PictureAustralia’ iSummit ’06 (iCommons Ltd, 2006) 22

77 ‘PictureAustralia’ iSummit ’06 (iCommons Ltd, 2006) 22

78 Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) ss51A and 110B

79 The Copyright Amendment Act 2006 (Cth) has introduced a new ‘open-ended’ library use exception in s 200AB of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) which may go some way to addressing this gap between library’s rights under the Act and common industry practices. However, until jurisprudence on the new exception develops, the scope of its effect will not be known with sufficient certainty to provide comfort to the clearance officers of most libraries. In particular, it will be interesting to see how the terms ‘normal exploitation’, ‘unreasonably prejudice’ and ‘special case’ included in the new s 200AB are defined. Even ignoring this uncertainty, the exception explicitly excludes any library activities that have a commercial or partly commercial aspect (eg as part as an exhibition or promotion).

80 See, for example, the broad licence grant in clause 3 and the restrictions in clause 4 of the Australian Creative Commons Attribution licence v2.5 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.5/au/legalcode> at 20 December 2006

81 Linda Greenhouse, ‘Justices Consider Status of Digital Copies of Freelance Work’ New York Times (New York) 29 March 2001, Late Edition, Section C, Page 3, Column 1.

82 ‘PictureAustralia’ iSummit ’06 (iCommons Ltd, 2006) 22

83 based on count available at ‘PictureAustralia: People Places and Events’ (2006) Flickr <http://www.flickr.com/groups/pictureaustralia_ppe/> at 1 January 2007

84 Heather Champ, ‘Snow in Vancouver Believe It or Not’ (2006) Flickrblog <http://blog.flickr.com/flickrblog/2006/11/snow_in_vancouv.html> at 1 January 2007

85 See, for example, ‘Flickr/Yahoo & Library collaboration’ (30 January 2006) Librarian.net <http://www.librarian.net/stax/1624> at 1 January 2006; Michael Porter ‘Flickr + Australia = Good On You’ (1 February 2006) Libraryman <http://www.libraryman.com/blog/category/flickr/> at 1 January 2007; ‘Yahoo/Flickr Teams Up With National Library of Australia’ (11 February 2006) ResearchBuzz <http://www.researchbuzz.org/2006/02/yahooflickr_teams_up_with_nati.shtml> at 1 January 2007; Jill Hurst-Wahl ‘Lorcan Dempsey and PictureAustralia and Flickr’ (10 August 2006) Digitization 101 <http://hurstassociates.blogspot.com/2006/08/lorcan-dempsey-on-pictureaustralia-and.html> at 1 January 2007

86 ‘Information’ Magnatune <http://www.magnatune.com/info/ethos> at 1 January 2007

88 Eepybird ‘Extreme Diet Coke and Mentos’ (2006) Revver <http://one.revver.com/watch/27335> at 1 January 2007

89 Paul La Monica, ‘Making Cash from Mentos’ (14 July 2006) CNNMoney.com <http://money.cnn.com/2006/07/13/news/funny/mentos_dietcoke/index.htm>

90 See, for example, Askaninja ‘Askaninja’ (2006) Revver <http://one.revver.com/watch/86608> at 1 January 2007

91 See, for example, lonelygirl15 ‘0023 A Peace Offering (and P. Monkey Boogies)’ (2006) Revver <http://one.revver.com/watch/56003> at 1 January 2007

92 See National Television Academy, ‘National Television Academy announces nominees, winners of Technology and Engineering Emmy Awards (Press Release, 2 November 2006) <http://www.emmyonline.org/emmy/advmedia_nom_release.html> at 1 January 2007

93 See Greg Bauman ‘Lonelygirl, YouTube Score TVWeek Viral Video Awards’ (2 November 2006) TVWeek <http://www.tvweek.com/news.cms?newsId=11009> at 1 January 2007