Deep

Impact On The Mobile Communications Market: A Case Study In Applying

The Regulatory Rules To Assess A Proposed Enterprise Combination

Jongho Kim PhD *

|

[Home] [Databases] [World Law] [Multidatabase Search] [Help] [Feedback] [DONATE] | |

United Kingdom Journals |

||

|

You are here: BAILII >> Databases >> United Kingdom Journals >> Deep Impact On The Mobile Communications Market(2008) 5:2 SCRIPT-ed 309 (2008) URL: https://www.bailii.org/uk/other/journals/Script-ed/2008/5_2_SCRIPT-ed_309.html Cite as: Deep Impact On The Mobile Communications Market(2008) 5:2 SCRIPT-ed 309 |

||

[New search] [Printable PDF version] [Help]

Jongho Kim PhD *

Ever since Alexander Graham Bell invented the telephone, communication technology has been developing. Now, no matter where you are, you can watch television or use hand-held mobile devices.1 Given that the telecommunications, computers and television branches of the communications industry are converging,2 this article examines a relatively recent Korean enterprise merger case – 2000 Kikyul 01293 – to analyse the manner in which highly developed technology often affects legal decisions and forces legislative or regulatory changes. It argues that the rapid evolution of high technology has rendered existing legislation obsolete or even counter-productive; the reason being that in technology development the bottom line is that the interests of the consumers who use an innovator’s results are closely related to the further development of that technology. In other cases, an enterprise’s prosperity and positive and negative feedback rely solely upon the consumers’ sacrifices.4 Thus, a discussion of this case will contribute to understanding not only the real-world enterprise’s competitive ability to survive the technology war, but also the notion that old or traditional rules and assessment standards can properly be applied in a quickly changing “market.”5 Although the case is Korean, I will apply both US and Korean competition law theory and precedents, thereby contributing to understandings of each country’s legal system and competition policy.

In Part 2, I describe current developments in the US and Korean communications market, issues being wireless communications market trends, and whether antitrust policy distinguishes between a traditional market and a “high-innovation market.”6 In this case it is more important to discern the manufacture of innovative products than the output of innovation itself.7 In Part 3, I introduce a Korean merger case, the question being: What is the relevant market and the standard for market demarcation? As there are only five competitors in the Korean telecommunications market, we should consider whether a government agency should permit a merger between two of them where there is no significant economic efficiency overlap between their business strategies. In Part 4, I review the criteria applied in merger assessments; in most of the merger cases filed with the Korean Fair Trade Commission (KFTC) where beneficial effects of innovation were alleged, the cases would likely have been challenged on the grounds of adverse impacts on competition in markets for existing services. In Part 5, I analyse competition issues in the mobile communications market. Here, the issue is whether the traditional approach to the assessment of a merger case in a high-innovation market is still valid, as the innovation market analysis, if still valid, may find anticompetitive effects in markets where the merging firms are neither actual nor potential competitors.8 In Part 6, I discuss the exceptions to the “combination of enterprises,”9 raising two issues: (1) whether the merger of enterprises is made with a non-viable company; and (2) whether efficiency gains are achievable through the merger of enterprises. The standards argued for do not necessarily represent a view as to what the law is or should be, but rather what firms may successfully argue in terms of legal, technological, or economic issues without running the risks of antitrust liability under any conceivable standard. In Part 7, I describe the KFTC’s corrective measures, the question being whether action by the KFTC is preferred over action by the company seeking the merger, and what alternative methods may exist to correct mergers which are in violation of the rule. Finally, in Part 8, I explain how the topic remains controversial.

Under the antitrust law paradigm, the above issues may fit together harmoniously. These questions underpin basic analytical tools for decision making against merger cases before the government agency. For the case examination, government authorities and judicial officials must have full knowledge about the high-innovation market. I determine that mobile communications markets belong to that of high-innovation market, so Parts 2 and 3 are interlinked. Generally, a merger case should be assessed under the traditional competition law principles (i.e., merger guidelines) even though it falls into the category of highly innovative technology cases. Furthermore, it should be examined under the given statute (i.e., Monopoly Regulation and Fair Trade Act) and if there was any violation of the rule or statute then the corrective measure and verdict can be brought. Therefore, in order to smoothen the analysis of the issues, the arguments from Parts 4 to 7 are closely related and logically linked with each other.

Drawing a sketch of the US and Korean wireless communications market is worthwhile because it helps delineate the formative policy for both the regulatory agencies and market participants and it provides useful information to consumers. The growth and success of the wireless communications market has had a pervasive effect in linked industries as well as a far-reaching influence on the national economy.10 However, if competition in the market disappeared, consumers would face higher prices, lower quality or quantity of mobile wireless services, or the delayed launch of new mobile wireless services.11 Moreover, the impact of regulations would certainly be both immense and lasting. The sector is also unique in the degree to which major money-spinner markets and industries depend on its development. To succeed in this market, all participants must keep abreast of market trends, current and next-generation levels of technology, and regulatory approaches.

Generally, “the objective of wireless communications is to provide ubiquitous coverage, enabling users to access the telephone network for different types of communications needs, regardless of the location of the user or the location of the information being accessed.”12 The wireless communications industry in the US is currently experiencing major upheavals,13 making it resemble an age of rival warlords. The mobile communications sector is among the “most competitive and least concentrated” in the world.14 The auctioning of an additional frequency spectrums pursuant to the Telecommunications Act 199615 (1996 Act) has led to more service providers coming into the market and significantly increased competition among them.16 In order to survive, service carriers are likely to customise the user-friendly services they offer to hyper-differentiate themselves from other competitors. However, taken together, the biggest trend in the communications market is the replacement of fixed-line with wireless services as technology evolves. For example, there was considerable upheaval in the US wireless communications sector in 2002 when the 1996 Act enabled phone number portability, allowing customers to keep their original phone numbers after transferring to different carriers.17 One study shows that when the scheme was announced, 800,000 wireline consumers switched to wireless numbers, and with only 100 million consumer home phone lines left, the fixed-line market is receding rapidly.18

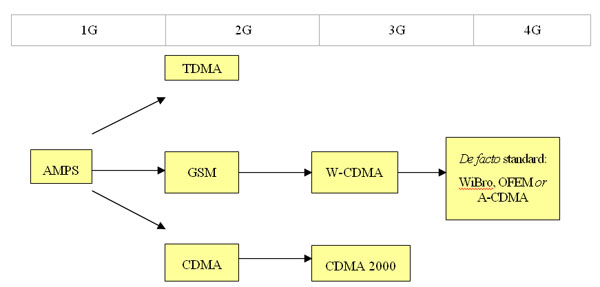

As with other countries’ market structures, the US wireless communications market consists of services providing support to the wireless infrastructure, handset telephones, and network infrastructure,19 but the US has never nationalised its telecommunications industry.20 As subscriber growth diminishes and the wireless subscriber market reaches maturity, service providers may change their competitive tactics by dropping prices associated with new customised applications and added service plans such as wireless internet access, text messaging, instant messaging, ringtones, mobile games, location-mapped emergency call services, and audio- and video-messaging services.21 This trend together with fourth generation (4G) Wi-Fi technologies will drive the future US communications market.22 Although land-line telephony does not suffer from wireless’s technological disadvantages such as dead zones, poor reception or dropped calls, the overall viability of wireless communication is no longer in doubt and in fact, is clearly indicated as a key driver of the communications industry platform and transmission.23 Figure 1 shows the competing wireless standards in the US.

Figure 1. Competing Wireless Standards24

With the introduction of new technologies such as 4G wireless services, WiBro, or Wi-Fi and WiMAX in the communications market, service providers and broadband operators will continue to see an increase in both wireless infrastructure and higher value-added revenue. Wireless services can also capitalise on location-mapped emergency call capabilities to win over customers who are averse to mobile services because of safety concerns.25 Further, service operators can also make handsome profits by pursuing “wireless internet applications” such as the hugely successful data-only broadband wireless. Such successful commercial innovation that enhances general consumer welfare and “economies of scale,” especially when they lead to lower prices and new services, have enabled the wireless segment to stay profitable even though its revenue was threatened by price-based competition. One example is that “while the average subscription price per minute dropped from 43.9 cents to 10.3 cents, the minutes per user grew from 140 to 483.”26

To support the mobile wireless communications business and facilitate technological innovation in the wireless communications markets (e.g., enhanced voice services quality and data and image file transport), wireless communications firms seek mergers as a way to enable them to continue in businesses and prevent further reduction of profits despite poor market conditions in the industry. One survey reported that “wireless subscribers increased from 109.5 million to 128.5 million during the year of 2001.”27 Another study reported that there were 130 million wireless subscribers in the US in 2003, with 28,000 being added per day.28 Note that technological innovations play a pivotal role in this dynamic story. Advancements in communication technology have played a key role in the New Economy, but they have also triggered a simultaneous avalanche of information whilst creating heightened consumer expectations.

Because of the expense and time involved in establishing a network and obtaining one of the limited number of spectrum resources licences regulated by government agencies, entry by a new player into the market would be extremely difficult. Even existing firms are seeking to merge as the market becomes increasingly competitive. The US wireless telecommunications market has consolidated rapidly, leaving only four major players: Cingular, Verizon Wireless, Sprint Nextel, and T-Mobile. These are considered nationwide carriers because they control licences in many areas across the country, giving them something approaching a national “footprint.”29

From a legal standpoint, competition in the telecommunications market has become a race among companies to deliver bundled communications services, including wireless telephony, wireless messaging and wireless internet. “The increase in frequency spectrum and the increase in number of service providers will both lead to increased competitive pressures in the industry.”30 Still, new competitive pressures are bearing down on all market participants. In this situation, where competition policy concepts are applied in the context of antitrust law enforcement and sector-specific telecommunications regulation issues arise, what is the appropriate balance between regulation and deregulation policy?

The harsh reality is that the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which was created, directed, and empowered by Congressional statute,31 has outlived its usefulness as an agency set up to preserve the now discredited “regulated monopoly” paradigm. The FCC was incorporated as the successor to the Federal Radio Commission; it is charged with regulation of all non-federal government use of the radio spectrum (including radio and TV broadcasting), and all interstate telecommunications (wire, satellite, and cable), as well as all international communications that originate or terminate in the United States. Unlike certain executive branch agencies, the FCC has the ability to issue orders and rulings with the force of law.32 In the arena of wireless communications, the Wireless Telecommunications Bureau (WTB) handles nearly all FCC domestic wireless telecommunications programmes, policies and outreach initiatives.33 The US regulatory structure offers three different licences for mobile services: cellular, personal communications service (PCS), and specialised mobile radio (SMR).34 As most communications markets lie between two extreme situations (collusion/negotiation and bitter competition), these are important factors in US telecommunications policy. Some may be saying that “sunk investments” have introduced a “winner’s curse” to the wireless market monopoly game; however, as the situation becomes more “winner-take-all,” so the competition law argument will be of more relevance. As the expanded scope and heightened level of customer demands place more stress upon communications operators, the standards of competition in any domestic market should be shaped by consideration of several factors, including licensing policy, service providers’ business strategies, and technology standardisation policy.

Currently, communication technology has reached the 4G level via the market players’ technological innovations, but a very significant investment of resources is still required to develop commercially viable technology. Unless otherwise competitively regulated, if one company wins the technology development race for the next generation of communications, it will enjoy all fruits of the market, including advantages in competition such as technology standards decisions, service prices, etc. In extremis, only a couple of companies who win the technology development races may survive in the global communications market.

US competition policy in the communications business sector has three key aspects: (1) there is no single policy, created and implemented at a single point in time; (2) there is no single agency or institution in charge of competition policy, but rather it is the result of a constant interplay between multiple agencies and industry actors, at multiple levels of jurisdiction, both horizontally (within the federal government) and vertically (between state, local and federal governments); (3) the US system mixes both broad competition law, which applies to any economic activity, with sector-specific regulation.35 Broadly, the mobile wireless telecommunications service is a relevant product market under s. 7 of the Clayton Act, 15 US C. §18. The US communications market is currently in transition to a reunified market in which it has always had competition as a goal.36 In this situation, three basic methodological steps are required in the antitrust regulatory process: (1) define the relevant geographic markets; (2) define the service carriers that have dominant market power in the relevant geographic markets; and (3) identify remedies to be applied to service providers having dominant market power to increase the level of competition.

With the 8 April 1997 launch of the new regulatory framework under the 1992 Horizontal Merger Guidelines which revised s. 4 regarding “efficiencies,” the concepts of dominant market power and position are entangled in a jungle of overhead wireless communication lines, with both concepts starting to be used interchangeably. As regulatory agencies such as the FCC, Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and Department of Justice (DOJ) try to analyse the competition level of the wireless communication market and define the service carriers having dominant power and position, they are taking various criteria into consideration.37 Note that:

… because the US competition policy approach involves both antitrust and sector-specific regulation, there is a balance between ex-ante and ex-post approaches. … FCC and state regulation is traditionally ex-ante. [In contrast] antitrust regulation—with the exception of merger pre-notification and review—involves ex-post enforcement. … Justice Department officials can investigate violations of the Sherman and Clayton Acts only after those violations have occurred. … Prevention of collusion and price-fixing relies on the threat of law enforcement or civil litigation, not administrative fiat.38

This multiple-check system has made a great contribution towards safeguarding consumer welfare so far. However, interestingly, the communications companies are undeterred by the uncertainties: “the future growth of consumer-based mobile communication systems will be tied closely to radio spectrum allocations and regulatory decisions that affect or support new or extended services, as well as to consumer needs and technology advances in signal processing and access, and network areas.”39

In the late 1990s, the new economy emerged as a central feature of the global economy, spreading like wildfire as an important issue in Korea.40 But what is new about the “new economy”? Despite recent opinions denying the concept following the erosion of start-up companies, volatile stock prices, and economic recession,41 there seems to be little disagreement that revolutionary developments in information and communication technology have brought about a paradigm shift in the economic system which is believed to have triggered the advent of the new economy.42 The “hallmarks” of the new economy can be identified as technology, globalisation, market power, and speed.43 But the most significant change has been the diminishing importance of traditional production factors such as land, labour and capital, and the rising centrality of knowledge and information as sources of competitiveness and wealth creation.44

Posner notes that the traditional industries are characterised by multi-plant and multi-firm production, stable markets, bulk order and mass production, heavy capital investment, modest rates of innovation, slow and infrequent entries and exits, and labour-intensive industries.45 While the importance of up-to-date working knowledge and information as emerging production factors is becoming evident across the whole range of industries along with the development of computer technology, it is particularly apparent in high-innovation markets such as those involving information technology and communications.46 Undoubtedly, a common characteristic of market players in high-innovation markets is their allocation of substantial resources to R&D together with a high degree of dependency upon intellectual property rights and well-educated human resources rather than raw materials, because knowledge and information are such crucial production factors.47 Ironically, a current innovation market is not only a product market, but also a technology market, as no one buys or sells intellectual property in an innovation market where firms teeter on the edge of viability.48 Under the market, intellectual property is characterised by heavy fixed costs relative to “marginal cost,” which is defined as the increase in the firm’s total cost that results when it increases its output by one unit.49

Accordingly, IP “is often very expensive to create, but once it is created the [reproduction cost] is low,” whereas the time needed to make additional copies is shortened.50 In addition, various firms’ vigorous efforts in R&D generate rapid technological innovations and shortened product life cycles in the market “while creating a business environment where market [participants] unable to promptly respond to changes cannot avoid being weeded out.”51 Such characteristics of high innovation markets can have profound effects on the shape of competition, as well as consumer social welfare.52 Thus, “the economic underpinnings of antitrust policy consist of propositions that relate competition to economic efficiency and consumer benefit, [b]ut those propositions strictly hold true only in a static world;” regardless of their sphere, they are no longer true in a world of technical change. But “does this make traditional antitrust policy and rules inapplicable [and thus the results unanticipated] when they are applied to innovative industries?”53 It has been stated that what seems to work best today is a solution that is more market-oriented and decentralised than we used a decade ago.54 Free market entry by a firm’s highly-developed “new technologies ... has opened the possibility of dynamic competition in which the dominant positions enjoyed by existing market players are collapsed, and earlier leading market players are replaced by new ones.”55

If a high innovation market fulfilled only the above-mentioned positive functions, it could serve as a highly beneficial driving force for reform in Korea’s communication markets where monopolistic market structures prevail.”56 However, as many practising lawyers, judges, economists and antitrust officials are already aware, high-innovation markets also have generic characteristics such as anticompetitive elements.57 In short, market properties such as network effects and switching costs operate based on deep-pocket factors as barriers to entry.58 This results in a tendency to entrench the market dominance of “first mover’s advantage.”59 Furthermore, “first movers can [freely] maintain their dominant position [in the market without slavish adherence to customer herd behaviour by] monopolising intellectual property rights as the key to generating knowledge and information, or by controlling the networks through which knowledge and information [is] distributed.”60

In effect, the first mover could twist the market around his/her finger. However, the KFTC has been developing policies to “prevent such potential adverse effects.”61 First, after watching market situations, the KFTC established the Review Guidelines on the Unjust Exercise of Intellectual Property Rights in 2000 to handle this subject.62 The aim of establishing these guidelines was to provide a specific guide for the application of competition law so that IP protection “would not stray from its original purpose of encouraging” firms to invest, in particular by being misused to hinder market competition for products or technology.63 While this was under way, “the KFTC set up another regulation which stipulates that firms who own essential facilities for production and sales in upstream or downstream markets should not limit access to their facilities by other firms.”64

Even in terms of enterprise combination and merger assessment (and without any sudden policy switch), the KFTC has explicitly clarified its keynote directions of ensuring long-term competition by taking into account the dynamic efficiencies framework brought about by technological innovation. However, no merger cases can be viewed as significant in such terms in Korea’s high-innovation markets. “Although there have been numerous cases of mergers among small-scale venture capitalist companies [in the last quarter-century,] none have been of much importance to competition policy.”65 Consequently, as an exception to the 1998-6 Guidelines, as amended, the KFTC has no merger assessment guidelines or regulations other than the conventional ones, which it can apply specifically to high-innovation markets.66

While the merger of Korea’s mobile communications companies discussed below “bear[s] many characteristics typical of high-innovation markets,” this merger still cannot be considered to have occurred in “a typical high-innovation market as such.”67 Though the merger of SK Telecom and Shinsegi Telecom – the last merger case of the twentieth century in Korea – “was assessed according to existing guidelines,” this merger may provide incipient lessons in many issues in the assessment of mergers in high-innovation industries, because the diverse characteristics relevant to high-innovation markets were taken into account in the review process of the tribunal.68

Regardless of the product or service market, “[o]ne of the virtues of a competitive market is that each seller or provider has the chance to succeed by providing the [consumer] public with cheaper or better products [and services].”69 In order to maintain those ground rules, antitrust policy should aim at promoting product efficiency. Thus, in preventing a market from becoming concretely anticompetitive, government enforcement plays a key role in monopoly policy by preventing company mergers from harming consumers.70 The consumer sustains injury when a service provider “charges high prices, but is arguably benefited if the [service provider’s] prices are low, even when its profits are substantial.”71 This proposition is quite possible even though the services are provided in the same market. Whenever an antitrust agency permits a merger to go forward, it should check whether the service provider is being mindful of the consumer’s wallet, as it must necessarily determine that the merger will not substantially harm consumer welfare.72 At this time, the calculation of market share is not only a starting point, but also a bottom line for determining whether monopoly power exists in the market. “However, without a definition of [the] market, there is no way to measure” a merging firm’s ability to destroy or reduce competition.73 Accordingly, I will examine a case involving a merger in the Korean mobile communications market which describes the relevant markets, and explain how the standard for telecommunications market demarcation will be examined.

In late 1999, the mobile communications company that held the largest market share, calculated on the basis of subscriptions (market share), took over, the third-ranking company.74 The acquiring company, SK Telecom (SKT), held 42.7% of the market share at the end of 1999, while the company acquired, Shinsegi Telecom (Shinsegi), held a 14.2% market share.75 This was a horizontal merger from a competition law perspective because it merged rivals in the same market.76 As SKT is a stock corporation whose core business area is mobile phone communication service provision, the company falls under the Korean MRFTA.77 Article 2.1 provides that the term “enterprise” means a juristic person who conducts a manufacturing, service, or any other business. Article 2.5 provides that any officer, employee, agent, or other person who acts in the interest of the enterprise shall be deemed as an enterprise with regard to the application of provisions pertaining to the enterprise’s organisation.

The

world is very different now from what it was when the statutes were

enacted, but determining whether a firm has monopoly power in the

market remains crucial, and involves two inquiries: (1) what is the

relevant market?; and (2) what is the relevant product market?78

The relevant market consists of the products and the geographic area

in which these products are produced and traded.79

According

to the one guideline, “[t]he relevant market of the product

comprises all those products [or services which are] interchangeable

or substitutable by the consumers in terms of characteristics,”80

quantity, service time, frequency in use, prices, and intended uses.81

Geographically, the relevant market consists of the area where the

products are consumed and “where the conditions of competition

are sufficiently homogeneous,” such as DVDs, films and books.82

“[This] can be distinguished from neighbouring geographic

business areas especially because the given competition conditions

and market structures substantially differ [in various ways].”83

Similarly, “the notion of geographic market also covers

services.”84

What

is the character of the mobile communications market, recalling that

mobile communications means the subscriber carries and uses the

telephone while on the move? This market

includes cellular

mobile phones, analogue and digital,

and PCS. Cellular

and PCS handsets send

out and receive electromagnetic waves in

different frequency bands (Cellular

800 MHz,

PCS 1,800 MHz),

but generally a user is not aware of the functional distinction, and

notwithstanding this difference, both are in the same market.85

Because the growth of the Korean domestic PCS market is closely

connected with the cellular market, a major substitution of demand

exists between each enterprise by level of charges and supplied

service, wireless connect method, channel bandwidth (approximately

1.23 MHz per channel),86

service area, target services (high-speed vehicle, pedestrian),

supplied service (voice, data), design or shape and price of phone

(KRW 250,000-400,000

level), and processing fees for new subscribers. The two systems’

service charge structures are similar. The fixed-line telephone

(inter-city call, toll call, and international call) market and

mobile phone market may be distinguished from each other by many

characteristics such as usage, investment in equipment and use of

communication network, charges, and business competitors. To provide

Wireless Calls, CT-2 Phone, and Trunked

Radio Systems (TRS),

Wireless Data Service uses a frequency assigned by the government,

with services similar to mobile phones. However, these fall into a

different market because they differ from mobile communication in

function and usefulness.87

The

International

Mobile Telecommunications-2000 (IMT-2000)

standard was excluded from the definition of the mobile

communications market because it was not in operation when the KFTC

rendered a decision on this company merger case.88

Communications

by land-line and internet-based media were also viewed as outside the

definition of relevant market because they have a different

connection diagram and are immobile.89

The

results revealed that besides the two cellular communications

companies, SKT and Shinsegi, three PCS providers competed in the

mobile communications market in Korea; Korea Telecom Freetel Co,

(KTF), LG Telecom Co, (LGT), and Hansol M.com (Hansol).90

Table 1 shows each player’s market share under three different

standards in the mobile communications market. Except

for the leading company, SKT, there was little difference among the

participants in terms of subscribers, earnings and call rates.

Table 1.

Market Share by Subscribers, Sales Earnings and Call Rate91

|

|

SKT |

Shinsegi |

KTF |

LGT |

Hansol |

Total |

|

Subscriber (person) |

9,731,766 |

3,239,134 |

4,162,549 |

3,041,094 |

2,614,656 |

22,789,199 |

|

(30/11/1999) |

42.7% |

14.2% |

18.3% |

13.3% |

11.5% |

100% |

|

Subscriber (person) |

11,268,948 |

3,608,813 |

4,678,726 |

3,508,242 |

3,042,187 |

26,106,916 |

|

Sales earnings (KRW billion) |

42,250.9 |

12,523.3 |

14,645.4 |

10,229.3 |

8,885.6 |

86,534.5 |

|

(1999) |

46.5% |

14.5% |

16.9% |

11.8% |

10.3% |

100% |

|

Telephone traffic (Call rate) |

81,652.0 |

20,317.3 |

27,920.0 |

20,440.1 |

17,470.0 |

167,799.4 |

|

(1999) |

48.7% |

12.1% |

16.6% |

12.2% |

10.4% |

100% |

According to the KFTC decision, the first mobile communications service in Korea was started by the Korea Mobile Communication Co, (KMC) in April 1984. The SK Group acquired KMC in December 1994, in accordance with “The Public Company Privatisation Plan” controlled by the Korean government. In April 1996, a second enterprise, Shinsegi Telecom, entered service, with competition thus emerging for the first time in the Korean mobile communications market. In March 1997 KMC changed its name to SKT. In October 1997, three PCS enterprises started full-time service nationwide, so five companies (including two cellular communications firms) were competing in the Korean telecommunications market. As of 1999, the Korean mobile communications market size was KRW 8.6 trillion, equivalent to USD 8.6 billion, with the leading company being SKT. The subscriber base in the Korean mobile communications market grew rapidly from 3,181,000 subscribers at the end of 1996 to 13,983,000 subscribers at the end of 1998, and to 23,443,000 at the end of 1999. This rapid growth was caused by the extension of subsidy grants after competitors had entered the market, a policy prohibited at one time by sunset law. Because services were quickly changing in high-innovation industries (e.g., communication network exchange), every company in the mobile communications industry needed to make large-scale investment to cope with the speed of technological development. The total equipment investment of the five companies reached KRW 9.7 trillion in 1999. The IS-95C and IMT-2000 projects also required substantial investment.

Table 2 shows the

market share changes in the first half of business year 2000

based on the number of subscribers. SKT’s market share halted

its downward trend in the first half of 1999 and began an upturn

during the second half of 1999. (As of September 2005, the

post-merger SKT had reduced its market share

from 57.0% on 31 March 2000 to 52.3% in its efforts to comply with

MRFTA antitrust provisions).92

Table 2. Change of Market Share by Subscriber (%)93

|

|

Post-merger, SKT |

KTF |

LGT |

Hansol

|

||

|

31/12/1998 |

42.7(55.8) |

15.3(14.5) |

58.0(70.3) |

16.8(12.2) |

15.1( 9.8) |

10.1( 7.7) |

|

31/12/1999 |

43.1(46.5) |

13.8(14.5) |

56.9(61.0) |

18.2(16.9) |

13.2(11.8) |

11.7(10.3) |

|

31/03/2000 |

43.2 |

13.8 |

57.0 |

17.9 |

13.4 |

11.7 |

According to the

decision, the IMT-2000 project, a next-generation mobile

communications service which can accommodate “data transfer

communication” “image transmission” and

“international roaming” entered service in May 2002.

However, the existing mobile communications market was expected to

persist for some time yet, because the speed of technological

progress under the second-generation system was still uncertain.

Table 3 shows mobile

communications service charges and their gradual reduction with

emerging competition. Table 4 shows the situation before and after

each company reduced its service charges on 1 April 2000. Compared

with its competitors, SKT’s call charge had been fairly high

but was greatly reduced. Thus, the standard charge gap was curtailed

from 23%-30% to 13%-18%. However, it is easy to see that the basic

charge was maintained at close to the prior level.

Table 3.

Changes in SKT’s Service Charge and Call Charge (10-second

unit) (in KRW)94

|

|

Jun. 1990 |

Feb. 1996 |

Dec. 1996 |

Sep. 1997 |

Jun. 1998 |

Jul. 1999 |

Apr. 2000 |

|

Call charge (midnight) |

18 |

23 |

20 |

18 |

18 |

13 |

11 |

Table

4. Competitors’ Service Charge Reductions on 1 April 2000 (in

KRW)95

|

|

SKT |

Shinsegi |

KTF |

LGT |

Hansol |

|

|

Daytime call charge (per 10-second unit) |

Before 31/03/00 From 01/0400 |

26 22 |

24 21 |

19 18 |

20 19 |

18 18 |

According to the

decision, six firms comprise the major phone suppliers in the Korean

mobile phone market, with Table 5 showing each company’s sales

and market share as of 1999. The total phone demand in the Korean

market was then KRW 5.3 trillion. Samsung Electronics Co, LGT, and

Motorola Inc, were the chief competitors in the cellular phone

market, with around 5% of the market share being taken by Hynix

Semiconductor Inc, and SK Teletec Co, However, one remarkable fact is

that SK Teletec’s market share in the cellular phone market

increased from 4% in 1999 to 8.7% in January-February 2000.

Table

5. Market Share Held by Korean Phone Manufacturers in 1999 (‘000/%)96

|

Supplier |

Cellular phone |

PCS phone |

Total |

|||

|

Sales |

% |

Sales |

% |

Sales |

% |

|

|

Samsung Electronics Co, |

4,044 |

49.7 |

2,774 |

37.2 |

6,818 |

43.7 |

|

LGT |

1,860 |

22.9 |

1,249 |

16.7 |

3,109 |

19.9 |

|

Hynix Semiconductor Inc, |

476 |

5.8 |

873 |

11.7 |

1,349 |

8.7 |

|

Motorola Inc, |

1,218 |

15.0 |

1,602 |

21.5 |

2,820 |

18.1 |

|

Hanhwa S&C Co, |

- |

- |

693 |

9.3 |

693 |

4.4 |

|

SK Teletec Co, |

326 |

4.0 |

- |

- |

326 |

2.1 |

|

Others |

210 |

2.6 |

272 |

3.6 |

482 |

3.1 |

|

Total |

8,134 |

100.0 |

7,463 |

100.0 |

15,597 |

100.0 |

|

Market size (KRW billion) |

27,869 |

52.2 |

25,520 |

47.8 |

53,389 |

100.0 |

A little earlier the

KFTC had taken stock of the various mergers and acquisitions that

were going on in the global communications market, with a view to

forming a basis for its own fair competition policy. However, mergers

between communications firms have their own distinct characteristics

depending on where in the world they are pursued. This is because

most cases are completed within a specific nation or geographic

region with regard to communication sovereignty.

It is not remarkable that horizontal merger cases should have been

successful within a given nation or region.

Hitherto, when a horizontal merger had been realised within the same market, under the MRFTA Article 16.2, the KFTC had taken corrective action against violators by ordering them to sell all or part of their shareholding. 97 This seems to suggest a principle that “is very much embodied in current procedure, which is a vastly higher degree of scrutiny [will be given to] mergers that ... represent a substantial change in the status quo than to the ongoing actions of some companies.”98

The KFTC reached the conclusion that “the merger by SKT with Shinsegi was anticompetitive.”99 Apart from the result, this conclusion contains many contentious points in its rationale.100 Of course, “not all horizontal mergers harm competition.”101 However, “the potential to harm competition is exceedingly evident when the result is to reduce the number of competitors.”102 First, by merging with Shinsegi, SKT met the expected “conditions of competition restraint” as described by the MRFTA, because SKT reached a post-merger market share of 60%.103 Under the MRFTA, if the number one company’s market share exceeds 50%, or if the total market share of the top three companies exceeds 75%, it is presumed to be an anticompetitive merger.104 A market share in excess of 70% is strongly suggestive of monopoly power,105 and thus generally held to be monopolising, as we see in numerous cases.106

Article 4 of the MRFTA provides that an enterprise whose market share in a particular business area falls under any of the following sub-paragraphs shall be presumed to be a market-dominating enterprise as referred to in Article 2.7 (i.e., the market share of one enterprise is 50% or more; or the total market share of not fewer than three enterprises is 75% or more). The same sub-paragraph provides that those whose market share is less than 10% shall be excluded. In particular, the already substantial level of customer concentration was expected to intensify with SKT’s reinforced market dominance arising from the network effects107 which are a unique characteristic of the mobile communications market. MRFTA, Article 2.7 further provides that a “market-dominating enterprise” means any enterprise holding market dominance who can determine, maintain, or change the prices, quantity, or quality of commodities or services or other terms and conditions of business as a supplier or customer in a particular business area, individually or jointly with other enterprises. Finally, in determining whether an enterprise is “a market-dominating enterprise” as to its market share, the factors taken into account include the existence (and extent) of any barriers to entry into its market and the relative size of competing enterprises (excluding enterprises whose annual total sales or purchases are less than one billion KRW).

The KFTC also recognised the existence of communications market entry barriers stemming from factors such as the frequency restrictions allocated by statute, high costs of initial capital investment for essential facilities which become sunk costs,108 strong brand loyalties created through various intensive advertising campaigns, and possession of communication technology.109 Finally, there were concerns over the possibility that cellular services would monopolise the demand for mobile phones, with the atmosphere growing tenser than before.110 “By using its monopolistic power in that area, SKT could force mobile phone suppliers to develop and sell cellular phones [rather than] PCS phones, which could result in accelerating the concentration of subscriptions to SKT by those subscribers with a strong preference for newly developed models.”111

Meanwhile, “SKT argued that the economic efficiency which was certainly derived from the merger outweighed the anticompetitive effects.”112 In other words, no matter what unfavourable side effects were produced, the merged business could generate tremendous efficiencies such as strategic synergy through the increased number of subscribers, business operating synergy by combining existing communications networks, and financial synergy by avoiding overlapping investment in R&D. However, although the KFTC did recognise some of the alleged economic efficiency gains, it rejected the petitioner’s argument on the grounds that the parallel operation of the two enterprises’ communications networks was unavoidable and that the effects of reducing R&D costs were not as significant as portrayed by SKT.113 Furthermore, the theory does not offer any guidance for distinguishing between eliminating duplication of R&D effort between the two merged companies, and cutbacks intended to reduce R&D to sub-competitive levels.114

Based on its judgment, the KFTC ordered corrective measures against SKT, including the demand that SKT reduce its market share to 50% within one year.115 “The measures also limited the quantity of mobile phones SKT could purchase from its subsidiaries within a certain period so that it could not depend entirely on the subsidiary for the purchase of mobile phones.”116

Some have argued that as technological innovation is undoubtedly the real key driver of economic progress, an increase in the rate of technological change can offset the adverse impact on consumer welfare from supra-competitive prices.117 However, I believe this argument stems from observation of conditions within high technology markets, which in fact differ from other markets in significant respects. In particular, these markets are characterised by rapid rates of technological development because enterprises pour all their efforts into knowledge-intensive technology. These vanguard markets also have striking features in high fixed R&D costs and sometimes strong “network effects.”118 At the same time, neither economic theory nor statistical studies support the assertion that highly concentrated markets promote R&D beyond a minimum viable scale or capital requirements; indeed, there is considerable evidence to the contrary.119

This being the case, restriction of competition resulting from company mergers (classified under Korean regulatory law by type as horizontal, vertical, or conglomerate mergers)120 will be examined in light of the business relationships among concerned parties, together with third parties and others because a merging firm is much indebted to the fostering of the market for what it has become. Whether a horizontal combination substantially restricts competition is judged by the comprehensive consideration of market concentration before and after the merger; the degree of foreign competition introduced and the international competition situation; the possibility of market entry; the possibility of collusion between competing businesses; and the existence of similar goods and adjacent markets.121 Thus, the KFTC’s test requires the petitioner to show that a merger will actively enhance competition rather than substantially reducing consumer welfare.122 Based on these standards a couple of issues will be discussed below.

When antitrust authorities evaluate the degree of market structure concentration, recent years’ trends must be considered. Where the trend has been towards a considerable increase in market concentration, mergers between businesses with high market shares may lead to a substantial restriction of competition. In such a case, factors including development of new technology, patent rights, and others must also be considered.123

The total market share

and relative sizes of the two leading

companies pre- and post-merger are presented in

Table 6. In this case, the restriction on competition resulting from

the merger is presumed as being beyond doubt. Because the disparity

of market share between the post-merger largest enterprise and its

nearest competitor reaches 38.6% points, it satisfies the MRFTA

Article 7(4).1 criterion as it was caused by an increase in the gap

stemming from the sharply rising disparity, while the second

company’s market share remained as before.

Table 6.

Mobile Communications Market Share (as of 30 Nov 1999, %)124

|

|

Before merger |

After merger |

|

SKT (No. 1) |

42.7 |

56.9 |

|

KTF (No. 2) |

18.3 |

18.3 |

|

No.2 ÷ No.1 (%) |

42.9 |

32.2 |

In this case, SKT (the petitioner), the largest enterprise by number of subscribers in the mobile communications market, acquired the third-ranked enterprise. Obviously, the competition structures in the mobile communications market worsened, as the number of competitors decreased from five to four. It is also understood that the petitioner’s market-dominating power would be stimulated and strengthened by “network externalities”125 resulting from the increased number of subscribers. Moreover, the merging of the two firms led to increases in the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI),126 which, according to the decision, increased by 1,213, from 2,669 to 3,882, and the petitioner’s market-dominating power also made conditions more difficult in the mobile communications market.

Because the mobile communications market is a network industry and securing subscribers is an indispensable requirement for business, if an enterprise succeeds in gaining and retaining more customers than other enterprises the network externalities will become much more likely and will increase the gap between the enterprises. Furthermore, customers are hesitant to switch brands because certain costs are associated with doing so.127 For example, a customer choosing to subscribe to a different service provider will incur additional expenses including subscription fees, security deposits, and phone purchasing costs. Above all, in Korean circumstances, nothing can prevent the customer’s phone number from changing. In view of the excellent quality of the petitioner’s services, it seems that most subscribers did not mind paying premium prices for them. In due consideration of these points, “demand elasticity”128 was low, and there was ample potential within the scope of the established markets to keep up this state of affairs for a long time. Here, the network externalities were apparently revealed by a survey of public opinion in November 1999, in which subscribers intending to cancel their subscriptions were classified by enterprise; SKT 4.0%, Shinsegi 12.0%, KTF 15.3%, LGT 21.7%, and Hansol 22.3%.129 The cancelling subscribers named their intended new service provider as follows: SKT 72.3%, Shinsegi 5.9%, KTF 12.6%, LGT 5.3%, and Hansol 4.0%.130 Therefore, by this analysis the merger clearly appears anticompetitive, and the KFTC’s ruling was sound.

If entry into the

concerned market can be made easily shortly after a merger, the

number of competitors reduced by a merger is likely to rise once more

and therefore the merger is less likely to substantially restrict

competition.131

The bottom line is that markets where entry is quick and easy are

highly competitive because they must be prepared to meet all consumer

demands.132

Under Korean law in force both now and at the time of the merger, the following factors are considered when assessing the likelihood of new entries:

(a) presence/absence of legal or institutional barriers to entry; (b) the amount of minimum capital required; (c) production technology requirements including patents and other intellectual property rights; (d) conditions of location; (e) conditions of purchase of raw material; (f) the distribution network of competitors and the cost of establishing sales networks, and (g) the level of product differentiation.133

Even though there has been an explosive growth in demand for communications services throughout the world, it is still not easy to enter the mobile communications market legally and practically. One example of a legal barrier is frequency restriction;134 in Korea, this restriction takes the shape of the need to acquire business approval from the Ministry of Information and Communication (MIC). The major practical difficulty facing any would-be entrant is the enormous start-up expense of obtaining the most modern equipment. Furthermore, if an enterprise enters an established market, it is even harder to get the necessary operating technology and open up service. Thus, it is almost impossible to imagine a new enterprise entering the existing market. In the sense of its language, the KFTC ruling successfully combines reasonableness and cogency, but omits an examination of each item of the provisions.

Probably the most important margin on which competitive pressure can be brought to bear in most of countries and firms is greater exposure to international competition through reduction of trade barriers to permit entry by foreign competitors.135 In the US, it has often been argued that special treatment is appropriate when assigning a share for a domestic market that includes foreign-based competitors.136 However, I am not so certain whether this argument also holds true in the Korean situation because the traditional comparative advantage case for international trade that economists teach is probably not as important today as the cases based on economies of scale and taking advantage of the large market effect.137 There is also still greater uncertainty in the high-technology market. This is especially true where exports take up a considerable portion of sales turnover and substantial competition exists in the international market.138 It would be also true in a market where importing is easy or imports take up an increasingly large percentage.139 In both these cases, a merger would be less likely to substantially restrict competition. In such cases, the following factors must be considered in order to assess the possibility of market entry by foreign competitors:

(a) international price and the status of supply and demand for the product; (b) extent of domestic market opening and the current status of foreign investment; (c) existence of a formidable international competitor; (d) customs tariffs and plans to alter them; and (e) non-tariff barriers.140

However, it is very difficult for foreign competitors to gain entry to the Korean mobile communications market.141 Foreign companies are barred from gaining frequency approval, and foreign investors in a Korean company are limited to a maximum shareholding of 49%.142 So the only opportunity for foreign investors to gain even limited access to the market is as a minority shareholder of a Korean company. It should also be noted that obtaining frequency approval from the MIC is a delicate problem that involves balancing economic, political, and military interests.

The notion of equal business opportunity at least justifies legal intervention to prevent business activity that significantly impedes the ability of a superior product to succeed in the marketplace.143 In addition, any such merger is likely to substantially restrict competition, with experience showing that this is the case if the decrease in the number of competitors as a result of the merger creates a situation conducive to explicit or implicit collusion on price, output, or terms of trade.144 Under KFTC guidelines, the case of collusion by competitors is to be assessed by examining the following factors:

(a) whether the price of the products sold in the relevant product market has been markedly higher than the average price of similar products not included in the relevant market; (b) whether enterprises in competing relations have maintained a stable market share for the past several years in the market where the demand for the product transacted in the relevant area of trade is inelastic; (c) whether there is high homogeneity among products supplied by enterprises in competing relations and whether the terms of production and sale of competitors are similar; (d) whether the information on the business activities of competitors is easily accessible; and (e) whether there have been cases of undue concerted acts in the past.145

In this case, the KFTC identified only a low possibility of undue collaboration between the petitioner and another company because SKT would have to obtain MIC approval for the subscription agreement.146 However, it might still have been possible for SKT to engage in undue collaboration in the area of mobile phone purchases, which are unrelated to subscription agreements. Therefore, the KFTC’s reasoning here appears to be defective.

If we can trust consumer sentiment, new subscriber attraction in the mobile communication market hangs on the subsidies for mobile phone purchases. As a leading company in the Korean mobile communications business, SKT had a great advantage in accumulated profits and completion ratio of depreciation, and thus was in an excellent financial situation.147 As shown in Table 7 below, SKT combined its subsidies policy with its earlier marketing strategy and saw 64.1% of new subscribers select SKT as their service provider.148 If SKT continued subsidies for mobile phone purchases, competition would become even more cut-throat and place SKT in a still better position to secure new subscribers; if not for the KFTC’s decision that SKT was engaging in foul play, this anticompetitive conduct would likely have skyrocketed.149

Table 7.

4/4 Quarter, 1999, New Subscribers and Net Increase (Person, %)150

|

|

SKT |

Shinsegi |

KTF |

LGT |

Hansol |

Total |

|

New subscribers |

1,835,090 (56.8) |

281,217 (8.7) |

430,222 (13.3) |

309,681 (9.6) |

377,351 (11.6) |

3,233,561 (100.0) |

|

Net increase |

1,207,196 (64.1) |

122,270 (6.5) |

192,852 (10.2) |

131,442 (7.0) |

228,856 (12.2) |

1,882,616 (100.0) |

As a result of the

merger, SKT held a 22.5 MHz cellular frequency band through its

integration and gained the upper hand in the market over the three

PCS firms, which had only a 10 MHz frequency band between them; thus

SKT could use frequency negotiations to gain

an advantageous position in the service

competition.151

After the merger, SKT’s brand loyalty could be expected to rise

because, as compared to other companies, SKT had more

dependable subscribers in the areas of telephone traffic, bill

payment, and disconnection ratio, as shown in Table 8. SKT’s

subscribers generally bought from them repeatedly over time rather

than buying from multiple service providers.152

Therefore, those considerations should also be taken into account

when judging anticompetitive conduct.

Table 8.

Subscriber Comparison (1999)153

|

Classification |

SKT |

Shinsegi |

KTF |

LGT |

Hansol |

|

Telephone traffic (Call rate per person) |

10,157.8 |

7,560.5 |

8,509.3 |

7,859.4 |

8,414.0 |

|

Monthly payment (KRW per person) |

39,626 |

35,776 |

32,268 |

30,283 |

30,543 |

|

Disconnection ratio |

7.8% |

13.7% |

16.1% |

13.5% |

10.1% |

SKT has lower fixed

costs than its competitors, i.e., a lower cost

per subscriber and operating cost per minute.154

The PCS frequency band requires more investment than the cellular

frequency band to provide the same standard of communication service,

so the PCS firms stand at a disadvantage

in this respect.155

Table 9.

Cost Comparison by Enterprise (1999)156

|

|

SKT |

Shinsegi |

KTF |

LGT |

Hansol |

|

Cost per subscriber (KRW) |

509,118 |

532,530 |

558,640 |

573,903 |

572,041 |

|

Operating cost per minute (KRW) |

144.0 |

155.0 |

156.3 |

168.0 |

160.3 |

As

SKT was the leading company in the mobile communications

market and had maintained a good financial status, its liability

ratio was comparatively low, and SKT had accumulated substantially

more earned surplus than its competitors; SKT had accumulated KRW

13,918 billion in profits while the three PCS companies accumulated

losses of KRW 2,860-5,385 billion.157

Table 10.

Financial Statements by Enterprise (as of 31 Dec. 1999)158

|

|

SKT |

Shinsegi |

KTF |

LGT |

Hansol |

|

Profits (losses) (KRW billion) |

13,918 |

(4,789) |

(5,385) |

(2,860) |

(3,160) |

|

FY 1999 Net-income (outgoings) (KRW billion) |

3,041 |

52.3 |

(590) |

(1,617) |

(451) |

|

Liability ratio |

66.0% |

574.7% |

151.3% |

196.4% |

191.6% |

|

Interest cost/ service sales |

3.11% |

9.8% |

11.7% |

16.5% |

9.0% |

Regarding equipment

investment depreciation (which is considered an expense, and thus

greatly affects a company’s financial situation), SKT’s

depreciation completion ratio (a measure of how quickly its

depreciating assets had been written off and thus removed from its

books) stands out conspicuously from those of its competitors; as of

31 December 1999, each competitor’s equipment depreciation

completion ratio was Shinsegi 32.3%, KFT 17.0%, LGT 16.6%, and Hansol

17.6% whereas SKT’s was 72.9%.159

On the advertising and sales promotion cost side, as compared with the three PCS companies, SKT adopted high-powered marketing strategies by spending 1.8 to 3.5 times as much money to secure subscribers. As of 31 December 1999, the rival companies’ budget lines for advertising and sales promotion were: SKT KRW 1,703 billion, Shinsegi KRW 517 billion, KFT KRW 947 billion, LGT KRW 634 billion, and Hansol KRW 489 billion.160

Communications network

coverage is also an essential criterion for evaluation of the mobile

communications business. As indicated by the number of network

switchboards and base stations,161

SKT invested more capital in increasing its network coverage than the

three PCS companies. Based on the enterprises’ respective

technology levels, even though the amount of money being invested for

equipment remained the same, there were huge differences in

communications service quality.162

Thus it may be presumed that SKT’s communications network

coverage was competitive. Furthermore, considering that Shinsegi was

the sole provider for the military, both companies’ superior

communications network coverage would be enhanced after the merger.163

Table 11.

Communication Equipment Investment by Korean Mobile Communications

Companies (as of 31 Dec. 1999)164

|

|

SKT |

Shinsegi |

KTF |

LGT |

Hansol |

|

Network switchboards (No.) |

48 |

22 |

19 |

20 |

18 |

|

Data system stations (No.) |

3,089 |

2,039 |

2,719 |

1,985 |

2,383 |

|

Amount of investment on main equipment (KRW billion) |

34,059 |

15,808 |

16,339 |

13,120 |

13,473 |

Let us recognise at the

outset that no economic model can demonstrate precisely the correct

breadth or scope of IP protection necessary to promote exactly the

degree of innovation that is best for society.165

However, in this situation, comparing the R&D side, including

researchers, IP rights, and investment of R&D, SKT had

overwhelmingly superior technology and research ability to that of

the three PCS companies.166

It is a good bet that the

petitioner’s distribution organisation could be boosted

substantially by the merger.167

Table 12.

R&D in the Korean Mobile Communications Industry (as of 31 Dec.

1999)168

|

|

SKT |

Shinsegi |

KTF |

LGT |

Hansol |

|

Researchers |

513 |

48 |

67 |

55 |

28 |

|

R&D operating cost (billion KRW) |

663.9 |

52.6 |

24.0 |

6.0 |

30.0 |

|

Intellectual property rights (cases) |

516 |

165 |

38 |

30 |

33 |

After SKT acquired

Shinsegi, it retained 1,837 exclusive agencies for the raw materials

it needed.169

The KFTC’s judgment was that SKT might become more competitive

by the merger, which would take on the existing exclusive agencies

and help maximise profits by introducing new products to the

nationwide market.

Table 13.

Agency Earnings by Enterprise and Type of Agency (as of 31 Dec.

1999)170

|

|

SKT |

Shinsegi |

KTF |

LGT |

Hansol |

|

Income per agency (KRW) |

2.19 billion |

1.30 billion |

1.30 billion |

0.77 billion |

0.66 billion |

|

Exclusive (KRW) (Number of agencies) |

2.19 billion (1,300) |

- (537) |

1.33 billion (1,072) |

1.00 billion (82) |

- (577) |

|

Non-exclusive (KRW) (Number of agencies) |

- (0) |

- (222) |

1.02 billion (113) |

0.75 billion (952) |

- (353) |

According to a Korean

Consumer Protection Board (KCPB) report, SKT had high brand power in

its service and goods, while the number of complaints filed with the

KCPB were at noticeably low levels.171

Table 14.

Consumer Complaints (raw figures/per 100,000)172

|

Classification |

SKT |

Shinsegi |

KTF |

LGT |

Hansol |

Total |

|

1998 |

47 |

93 |

79 |

48 |

35 |

302 |

|

1999 |

216 |

363 |

416 |

372 |

347 |

1,714 |

|

1999 average subscriber total |

8,038,422 |

2,687,300 |

3,310,232 |

2,600,734 |

2,076,134 |

18,712,822 |

|

Complaints per 100,000 persons |

2.7 |

13.5 |

12.6 |

14.3 |

16.7 |

9.2 |

The requirement to obtain government approval for its subscription charge made it impossible for SKT to build up a monopoly or an oligopoly within a short period.173 After the merger, to exclude its competitors, SKT avoided increasing subscription charges as far as possible.174 As a result, SKT’s market-dominating power would be bolstered, and the PCS companies’ ability to compete was likely to be reduced.175

The most notable quality of the communications industry is its speed in technological development and use of high technology.176 Generally, if enterprises employ the best available technology in business, they can supply services at lower cost and continually reduce their charges, subject to availability. However, experience shows that if competition is absent from the market, charge reduction will not happen or will be delayed. The subscription agreement approval system makes it difficult for SKT to decrease its charges (as opposed to simply suppressing any increase). Because the requirement for government approval before setting a new subscription charge rate to its customers would not apply after SKT merged with Shinsegi, the petitioner could set competitor exclusion in motion.

In the case of mergers

where technological innovations are in prospect, there is no escape

from the question of whether the gains to consumers from

merger-dependent innovation are likely to outweigh any

anticompetitive effects of the merger.177

If we accept the above diagnostic uncritically, after the merger SKT

would become a “monopsony”178

in the cellular market through its demand control over subsidiary

company SK Teletec’s products, with the fear that this would

impede the competition.179

Table

15. SKT’s Cellular Phone Purchasing Ratio from SK

Teletec (number of phones, %)180

|

|

SKT total purchases |

Total SKT purchases from SK Teletec |

Ratio |

|

1999 |

6,101,000 |

326,000 |

5.3% |

|

Jan.–Feb. 2000 |

1,189,000 |

143,000 |

12.0% |

SK Teletec, one of the

pioneers of cellular technology, manufactures its phones at

production facilities installed at Sewon Telecom Co, moreover, SK

Teletec has been importing IM-1100 phones from Kyocera Co, in Japan

and processing them at Sewon since December 1999 before releasing

them into the market. As of 31 March 2000, the company’s

cellular phone production had reached 100,000 per month.181

Table 16.

SK Teletec’s Phone Manufactures by Production Facility182

|

|

1999 |

Jan. – Feb. 2000 |

||||

|

Sewon Telecom |

Import (Kyocera) |

Total |

Sewon Telecom |

Import (Kyocera) |

Total |

|

|

Supply |

319,200 |

6,800 |

326,000 |

114,000 |

29,000 |

143,000 |

The KFTC concluded that

the formation by SKT of a monopsony in the cellular phone market was

likely to restrict competition within the mobile communications

market. After applying high technology to its cellular phones, the

petitioner would have a monopoly on them. The

application of high technology to current business schemes would help

induce customers to join SKT by appealing to the customer’s

preference for new model cellular phones.183

As discussed above, it was presumed that this case would result in restricted competition in the form of market concentration; it would bring about decreasing competition by creating an imbalance between the firms’ market shares and would also decrease the number of firms in the market. In addition, after the merger, it was feared that the “strain effect” (or herd behaviour) from network externalities would emerge in the mobile communications market. For the time being at least, no new market player would emerge in the mobile communications industry; SKT had a better financial structure, distribution organisation, research and development ability, and communication facilities than its competitors, so it seemed that in every respect competitiveness would decline in the market. All issues considered, this case demonstrates how the nature of a market can “practically suppress competition in a particular business area.”

In addition, SKT’s reinforcement of its market-dominating position in the mobile communications market would delay charge reductions, additional service development, etc., with damage to consumers being abundantly clear. Demand elasticity in the mobile communications market was so low that the distortions in the market structure were likely to remain for a long period of time.184 Finally, even in the phone market, it was probable that competition would be restricted by SKT’s monopsony of the cellular phone.185

In 1992, for the first time since the 1968 and 1982 guidelines, “the [US DOJ and FTC] joined in promulgating horizontal merger guidelines.”186 Notably, “[t]hese guidelines were offered as a framework of analysis of the adverse competitive effects of a given merger.”187 However, the US “antitrust laws were passed for the protection of competition, not competitors.”188 Since 1999, US mobile communications firms have achieved national coverage by acquisition and merging firms. Unlike Korea’s single merger assessment, however, the US adopted a dual review system – the FCC analyse the merger and it then proceeds separate from DOJ.189 In merger approval hearings, the FCC examine factors based on the number of competing enterprises, the HHI, and the degree of horizontal concentration compared its degree in the global market. FCC tried to analyse not only the competition situation in the communication market, but also the public benefits which would occur from the merger.190 The significant public benefits means:

(i) [d]eployment of broadband throughout the entire [region that covered by both firms], (ii) [i]ncreased competition in the market for advanced pay television services due to [merging firm’s] ability to deploy Internet Protocol-based video services more quickly than [merged firm] could do so absent the merger, (iii) [i]mproved wireless products, services and reliability due to the efficiencies gained by unified management of [the merged firm], (iv) [e]nhanced national security, disaster recovery and government services through the creation of a unified, end-to-end IP-based network capable of providing efficient and secure government communications, and (v) [b]etter disaster response and preparation from the companies because of unified operations.191

Meanwhile, FCC analyses merger effects that influence competition in the multiple main markets. They are: (i) special access competition; (ii) retail enterprise competition; (iii) mass market voice competition; (iv) mass market internet competition; (v) internet backbone competition; (vi) international competition.192

The analysing tool for a decision is standardised, so how a horizontal merger affects market competition and the anti-competition of its combination is easily weighed. Antitrust law uses this as the groundwork for setting guidelines. On the other hand, there is no unanimous agreement on whether vertical combination causes negative effects on competition although the guidelines for vertical mergers in the antitrust law are changing with the trend in academic study. Therefore, one important policy lesson can be seen: there are no fixed merger assessments standards for mobile communication firm merger cases and it differs from one jurisdiction to the other.

Antitrust law has

always been concerned with anticompetitive practices of market

players that permit a firm to obtain or maintain a dominant share of

a market despite its product’s qualitative inferiority.193

The petitioner is required to give sufficiently clear evidence that

the merger will enhance and promote competition rather than eliminate

it. As a matter of theory, even though there is no threat to

competition in any existing relevant market, it is possible for a

merger to threaten consumer benefits by reason of a decrease in

innovation.194

Thus, the anticompetitive effect must be assessed by the agency to

see if the firm’s business scheme and its conduct are found to

have the necessary connection to the monopoly.195

Meanwhile, it should be noted that traditional antitrust merger

enforcement rests on a rough consensus about the relationship of

market performance and market structure. In contrast, innovation

market enforcement primarily aims to regulate the structure of

innovation markets so as to enhance the level of resources devoted to

R&D.196

In short, the innovation market analysis, which has received

extensive criticism, is simply a tool to aid the analysis of

theoretical model and competitive effects.197

It is sometimes claimed that antitrust policy standards should not be applied to innovative industries because those industries change more quickly than the judicial system can react, making any monopoly power transient and any relief irrelevant.198 Here, my argument is not that it is more or less likely for firms to have market power as commonly shown by market share,199 but only that the appropriate tests for assessing such power are very different from those now commonly in use.200 It is definitely true that in the context of innovative and quickly changing industries, to attain a regulatory goal, antitrust policy must be carefully applied with due consideration of consumer benefits. In such industries, it would be wrong to look only at static gloomy situations, which simply provide a snapshot in time rather than a real-time motion picture of what is going on. Hence, in deciding whether to approve, prohibit or prosecute, antitrust authorities should consider whether the situation can be self-correcting with simple measures, because sometimes it may be better to leave the market to its own devices. Further, the dramatically and incessantly changing nature of the industry must be taken into consideration in deciding whether an enterprise’s allegedly anticompetitive business conduct can be reasonably supposed to be aimed at the suppression of competition, if it is apparent that it is not going to be effective anyway.201

However, even though no

authoritative definition of

high-innovation markets yet exists,202

the nature of the mobile communications market accords with many of

the characteristics commonly attributed to most high-innovation

markets.203

In other words, the mobile communications market in Korea involves

traditional market structure characteristics under business

environments in addition to numerous high-innovation market ones. To

begin with, “a speedy technological advance not only enables

the market for mobile communications to undergo rapid changes in the

services [provided],” but also initiates consumers into

modernised technology.204

Granted, as of 2000, it was less than 20 years since mobile

telephones had come into regular use in Korea, but the market

territory created by the use of cellular phones was quickly

encroached on by PCS and mobile cellular services. The

next-generation IMT-2000, launched in 2002, was expected largely to

supplant the earlier services and thus to lead

a paradigm shift in the communication technology generation.205

Admittedly, “cellular phone services have been momentously transformed from the initial analogue type which has been conventionally used to the digital;”206 as a consequence, analogue services, in which a base carrier’s alternating current frequency is modified by varying the frequency or the amplitude of the signal (in order to add voice or other information), are not provided in Korea. “The speed of technological innovation has also consistently increased, unimaginably enabling PCS to dominate half the market only five years since its introduction.”207 Moreover, “necessary technological innovations under the inspiration of the computer science mode are actively supported by the new knowledge-based economy and consistent investment in R&D.”208 According to the 1995 US Intellectual Property Guidelines,209 even though we cannot explain beyond reasonable doubt or predict how a change in the structure of a relevant innovation market will affect the amount of R&D effort, the innovation markets consist of the R&D directed to particular new or improved goods or processes and the close substitutes for that research and development.