COVID-19: This judgment was handed down remotely by circulation to the parties' representatives by email. It will also be released for publication on BAILII and other websites. The date and time for hand-down is deemed to be 10:30hrs on 29 July 2021

58. Easylife does not produce the items it sells. It sells items, purchased from suppliers, often branded with the easylife logo. One possible description of the business is that it deals in retail sale of a variety of clothing, homewares, household goods, gadgets, motoring accessories, and health and mobility items targeting the over 65-year-old demographic. The description, however, is not complete. Mr Caplan (the second Defendant) explains:

“Easylife has also developed a range of its own brands which don’t have the word easy in them. For example Easylife has a range of watches and clocks, sold under the Tavistock & Jones brand (which is also abbreviated to T & J on the products), the Good Ideas brand (which we use for various cleaning/disinfecting products including the Oven Genie product), Schloff for mattress toppers and other bedding products, Cucinare, for kitchen products, Featherlight for shoes, Happy Feet for foot products, GoHeater, and the Genius brand which is used on our Safety Ladder and numerous other products. Easylife has also sold many products bearing third party brands such as Cataclean catalytic converter cleaner, some Westland lawn care products, Sursol hand sanitisers and many others.”

73. Other such products and the dates on which the Defendants began use of the EC Sign are:

73.1. ‘Shoe Stretch Cream’ (from January 2011);

73.2. ‘Stone, Patio and Decking Cleaner’ (from September 2011);

73.3. ‘Cat & Dog Stayaway’ (from September 2011);

73.4. ‘Spider StayAway [sic]’ (from September 2011);

73.5. ‘uPVC Reviver’ (from April 2012);

73.6. ‘Mattress Cleaner’ (from October 2011);

73.7. ‘Mattress Stain Remover’ (from July 2012)

73.8. ‘Washing Machine Disinfector’ (from March 2012);

73.9. ‘Moth Repellent Spray’ (from September 2012);

73.10. ‘Spray n Seal - Black’ (from January 2013);

73.11. ‘Spray n Seal - Clear’ (from January 2013); and

73.12. ‘Frost Free’ (from April 2013)

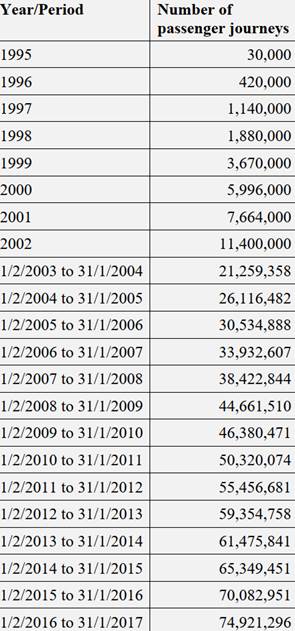

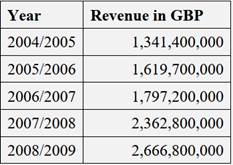

76. The scale of the easylife business is not questioned by easyGroup. It has relevance to the complaints made in respect of the business relied upon by easyGroup as evidence of detriment. The uncontested evidence of Mr Caplan is as follows:

The number of mailings sent out by Easylife Holdings would have started at a few hundred thousand per year (using my Home Free and Ideal Home databases). By 2005/2006 we would have been mailing about 500,000 easylife branded catalogues quarterly to our database (owned and bought) and inserting into national and regional newspapers and magazines at least 50 million white label/co-branded catalogues and at least another 50 million Easylife branded catalogues a year. The key to the success of my business is high volume, in order to benefit from the economies of scale of printing catalogues, purchasing product from China and fulfilment processing. The higher the volume, the lower the cost per unit and per order. At that time, the web traffic accounted for less than 10% of orders, as it wasn’t until home broadband became much more established that our 65+ year-old customers started ordering online, even then, it was less than 20% until 2015, and is only slightly higher today, circa 25% - 30%.

Like most businesses Easylife has had its share of ups and downs in terms of trading volumes, being affected by the financial crash and numerous other issues. However by 2010/2011, Easylife was distributing about 150 million insert catalogues in newspapers and about four to five million catalogues were being mailed to our database. By 2010/2011 the internet was becoming much more significant and we were likely getting hundreds of thousands of visitors a year to the site by that point. The turnover from 2010 to about 2016 would have been about £15m a year. From 2016 we put a lot of effort into growing the business through general expansion with the purchase of a major competitor, Tensor Marketing Ltd and by offering a bigger book with a greater number of pages and products. Since 2016 our annual turnover has more typically been about £30 - 35m. Now in our 21st year, we have inserted well over one billion insert catalogues and mailed out well over one hundred million catalogues to our customer database and served over 5 million customers, with over 10 million orders.

104. Section 9 provides the “proprietor” of a trade mark with exclusive rights in the trade mark that is infringed. The acts amounting to infringement, if done without the consent of the proprietor, are provided for in section 10:

(1) A person infringes a registered trade mark if he uses in the course of trade a sign which is identical with the trade mark in relation to goods or services which are identical with those for which it is registered.

(2)A person infringes a registered trade mark if he uses in the course of trade a sign where because—

(a)the sign is identical with the trade mark and is used in relation to goods or services similar to those for which the trade mark is registered, or

(b)the sign is similar to the trade mark and is used in relation to goods or services identical with or similar to those for which the trade mark is registered, there exists a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public, which includes the likelihood of association with the trade mark.

(3)A person infringes a registered trade mark if he uses in the course of trade in relation to goods or services, a sign which—

(a)is identical with or similar to the trade mark,

(b). . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .where the trade mark has a reputation in the United Kingdom and the use of the sign, being without due cause, takes unfair advantage of, or is detrimental to, the distinctive character or the repute of the trade mark.

(3A) Subsection (3) applies irrespective of whether the goods and services in relation to which the sign is used are identical with, similar to or not similar to those for which the trade mark is registered.

105. Section 46 specifies the grounds upon which a trade mark may be revoked:

(1) The registration of a trade mark may be revoked on any of the following grounds—

(a) that within the period of five years following the date of completion of the registration procedure it has not been put to genuine use in the United Kingdom, by the proprietor or with his consent, in relation to the goods or services for which it is registered, and there are no proper reasons for non-use;

(b) that such use has been suspended for an uninterrupted period of five years, and there are no proper reasons for non-use;

(c) that, in consequence of acts or inactivity of the proprietor, it has become the common name in the trade for a product or service for which it is registered;

(d) that in consequence of the use made of it by the proprietor or with his consent in relation to the goods or services for which it is registered, it is liable to mislead the public, particularly as to the nature, quality or geographical origin of those goods or services.

(2) For the purposes of subsection (1) use of a trade mark includes use in a form (the “variant form”) differing in elements which do not alter the distinctive character of the mark in the form in which it was registered (regardless of whether or not the trade mark in the variant form is also registered in the name of the proprietor), and use in the United Kingdom includes affixing the trade mark to goods or to the packaging of goods in the United Kingdom solely for export purposes.

(3) The registration of a trade mark shall not be revoked on the ground mentioned in subsection (1)(a) or (b) if such use as is referred to in that paragraph is commenced or resumed after the expiry of the five year period and before the application for revocation is made:

Provided that, any such commencement or resumption of use after the expiry of the five year period but within the period of three months before the making of the application shall be disregarded unless preparations for the commencement or resumption began before the proprietor became aware that the application might be made.

(4)An application for revocation may be made by any person, and may be made either to the registrar or to the court, except that—

(a)if proceedings concerning the trade mark in question are pending in the court, the application must be made to the court; and

(b)if in any other case the application is made to the registrar, he may at any stage of the proceedings refer the application to the court.

(5)Where grounds for revocation exist in respect of only some of the goods or services for which the trade mark is registered, revocation shall relate to those goods or services only.

(6)Where the registration of a trade mark is revoked to any extent, the rights of the proprietor shall be deemed to have ceased to that extent as from—

(a)the date of the application for revocation, or

(b)if the registrar or court is satisfied that the grounds for revocation existed at an earlier date, that date.

109. The first in time was Mr Anderson. He explained that he was employed as Head of Marketing at easyJet between 1 May 1995 and 30 November 1998. He was also employed by easyCafe (trading as easyEverything) as Marketing Director between 1 December 1998 and 31 March 1999 and employed by easyGroup as Marketing Director between 1 April 1999 and 10 March 2000. His full-time employment ended at that point but has had some involvement as a consultant since. His current role is “brand historian”. He did not have first-hand knowledge of the licensing arrangements in respect of easyGroup in the period 2000-2010. His source of information was a friend who worked at easyGroup and his research. The research was primarily based on articles written about the easy+ companies. He accepted the following in cross examination:

109.1. he had been paid by easyGroup to provide his witness statement and for his time at court.

109.2. he understood that easyKiosk was “only ever” used for the purpose of selling items such as food and drink during a passenger flight.

109.3. easyKiosk was not separate entity: it was not a trading company. Neither was easyRider, easyTech or easyLand.

109.4. part of his role was to help bring the 16 brands existing at that time together under one umbrella, that being easyGroup.

109.5. easy.com was set up to assist with the umbrella concept.

109.6. easyBank did not materialise: “Stelios was often talking about new ventures. An idea is not the same as establishing a company.”

109.7. He was not sure that easyKiosk or easyLand could be “classified as a venture”. easyKiosk is a licencsed to an operator.

109.8. easyGroup was not a venture in its own right. It provided services in support of the licensees.

Assessment

138. One particular exchange between counsel and Mr Chrystostomou is worth setting out as the witness was asked directly about confusion on behalf of a customer. The witness could not see how a customer would make a link with easyGroup, an umbrella company holding intellectual property and dealing with licensees, and easylife where they had completed an order form in a catalogue to supply batteries:

“Q. Okay, are you -- you say it looks like it, can people cut and paste e-mails into Priam?

A. You can cut and paste contents of an e-mail into Priam.

Q. Is that generally what your telephone service operators do, do they cut and paste e-mails in, or the e-mail responders?

A. Sometimes. They can do either. It depends how the e-mail is and whether -- how much of it is relevant to the customer’s issue and query.

Q. Okay. So here there is a comment has been made, and the notes are here on Priam and can we just read them together?

A. Yes.

Q. It says: "Thank you for your reply e-mail" -- I think it looks like it is a complaint or a query about a missing alkaline battery charger being out of stock, yes?

A. Yes.

Q. And then attempts to phone customer services on two occasions, delays, which is unfortunate, and then "When the opportunity to speak to a member of easyGroup is possible the telephone line was disconnected!" There we have someone who is calling, and it happens, an unfortunate thing has gone on, but they have, or they have sent an e-mail, someone has sent an e-mail and they have mentioned easyGroup and they could be referring as an abbreviation to Easylife Group, could they not?

A. I would think it is exactly what happened.

Q. Or they could be referring to easyGroup thinking it is a connection with my client, it is possible?

A. Only if he sells alkaline battery chargers.

Q. Well, no, because if they were confused as to some sort of connection they could certainly think there was a connection with the easyGroup, could they not?

A. No, but this e-mail is in relation to some items ordered from Easylife and I do not see the connection, myself, but we all have our views, I guess.”

144. Cross examination exposed the nature and extent of the calls received at the call centre (overflow from First Choice or sales calls) would not ordinarily incorporate an opportunity for a complaining customer. There was limited opportunity for this call centre to deal with confused customers in recent years but there was a time when it did deal with complaints:

“Q. And in terms of thinking back to the overflow sales calls, if a customer calls to place an order based on the catalogue, because that is where they dial the number from, right?

A. They do, yes.

Q. Even if they were confused -- just assume for me at the moment, assume they were confused that Easylife Group was in some way connected to easyGroup, my clients, yes?

A. Yes

Q. You cannot think of any reason why they would mention it to you in the sales call, can you?

A. No…

So the opportunity for you to become aware of confusion or some misapprehension between Easylife Group and my clients really only arises in complaint calls or e-mails, which you do not deal with?

A. Mm-mh, yes…

Q. So unless someone during this time, so when you were doing customer service calls, mentioned easyJet or Stelios to you, there is no way that you or your DRMG colleagues would be aware of customer confusion in the period when you were carrying it out. That is right, is it not?

A. Yes, that is right.

Assessment

167. In particular I find, as a matter of fact, that Mr Caplan’s evidence may be relied upon in respect of the following matters:

167.1. he only became aware of easyGroup in March 2013 after he received a letter before action from easyGroup;

167.2. he was not seeking to gain an advantage by using the word “easy” before the product name, domain name or any of the signs;

167.3. to extend his existing business from catalogue to online he acquired easlifeonline.com in February 2000 and set up easylifeonline in March 2000;

167.4. easylifeonline changed to easylife;

167.5. the extension from catalogue to online built on the extensive database of the existing companies including GCE;

167.6. easylife was chosen to describe the ethos of the existing business which was to sell products that “solved every-day practical problems and so made life just a bit easier for its 65+ year old customers”;

167.7. he knew of easyJet before using “easy” but did not know of any of the easyGroup’s alleged “family of brands”;

167.8. one line of product sold related to cleaning. easylife has sold hundreds of different types of cleaning and personal care products;

167.9. easylife developed a number of joint venture relationships with the national newspapers and publishers to produce own brand insert catalogues for them, essentially white labeling variations of the Easylife catalogues for the News of The World, the Sun, the Daily Mail, the Mirror, the Telegraph, the Guardian, the Radio Times, etc. Some of those catalogues were co-branded with easylife;

167.10. due to a failure to supply during the pandemic the Guardian newspaper dropped easylife as an advertiser;

167.11. the reorganisation of easylife in 2003 was done for rational reasons unrelated to easyGroup;

167.12. the reorganisation led to the acquisition of easylifegroup.com in January 2004 which is likely to have been before Mr Caplan had heard of easyGroup;

167.13. the success of easylife depended on turnover. In the year ending 2006 it had mailed 500,000 branded catalogues quarterly to its database and inserted in the region of 50 million catalogues into national newspapers which rose to 150 million by 2010;

167.14. it is estimated that the business has served 5 million customers with over 10 million orders;

167.15. there was no intention to build a family of brands. Other brands were used as well as “easy” such as “Wenko” and GCE;

167.16. the acquisition of easy-life-group.com was to prevent third parties from using it. It is more likely than not that the acquisition occurred prior to the letter before action was received from easyGroup. The use of the domain is to point to easylife’s website;

167.17. easylife launched three products under the easycare brand being a stairlift cleaner, a mobility scooter cleaner and a wheelchair cleaner. The sales of those products were very poor and all three lines were discontinued quickly. However existing stock continued to be sold; and

167.18. easylife did not intend to deceive the public into thinking there was an economic association between it and its products, signs or domain and easyJet or easyGroup.

203. Arnold J provided a summary of principles applicable to this area of trade mark jurisprudence in The London Taxi Corp Ltd (t/a London Taxi Co) v Frazer-Nash Research Ltd at [217]-[219]. His judgment was affirmed on appeal. He applied this in W3 Ltd v Easygroup Ltd at [194]–[195]:

“(1) Genuine use means actual use of the trade mark by the proprietor or by a third party with authority to use the mark ….

(2) The use must be more than merely token, that is to say, serving solely to preserve the rights conferred by the registration of the mark: ….

(3) The use must be consistent with the essential function of a trade mark, which is to guarantee the identity of the origin of the goods or services to the consumer or end user by enabling him to distinguish the goods or services from others which have another origin: ….

(4) Use of the mark must relate to goods or services which are already marketed or which are about to be marketed and for which preparations to secure customers are under way, particularly in the form of advertising campaigns: …. Internal use by the proprietor does not suffice: …. Nor does the distribution of promotional items as a reward for the purchase of other goods and to encourage the sale of the latter: …. But use by a non-profit making association can constitute genuine use: ….

(5) The use must be by way of real commercial exploitation of the mark on the market for the relevant goods or services, that is to say, use in accordance with the commercial raison d'être of the mark, which is to create or preserve an outlet for the goods or services that bear the mark: ….

(6) All the relevant facts and circumstances must be taken into account in determining whether there is real commercial exploitation of the mark, including: (a) whether such use is viewed as warranted in the economic sector concerned to maintain or create a share in the market for the goods and services in question; (b) the nature of the goods or services; (c) the characteristics of the market concerned; (d) the scale and frequency of use of the mark; (e) whether the mark is used for the purpose of marketing all the goods and services covered by the mark or just some of them; (f) the evidence that the proprietor is able to provide; and (g) the territorial extent of the use: ….

(7) Use of the mark need not always be quantitatively significant for it to be deemed genuine. Even minimal use may qualify as genuine use if it is deemed to be justified in the economic sector concerned for the purpose of creating or preserving market share for the relevant goods or services. For example, use of the mark by a single client which imports the relevant goods can be sufficient to demonstrate that such use is genuine, if it appears that the import operation has a genuine commercial justification for the proprietor. Thus there is no de minimis rule: ….

(8) It is not the case that every proven commercial use of the mark may automatically be deemed to constitute genuine use: …”

Proposition (3) has subsequently been reinforced by the ruling of the CJEU in Case C-689/15 W.F. Gözze Frottierweberei GmbH v Verein Bremer Baumwollbörse [EU:C:2017:434], [2017] Bus LR 1795 that:

“Article 15(1) of …. Regulation … 207/2009 … must be interpreted as meaning that the affixing of an individual EU trade mark, by the proprietor or with his consent, on goods as a label of quality is not a use as a trade mark that falls under the concept of ‘genuine use’ within the meaning of that provision. However, the affixing of that mark does constitute such genuine use if it guarantees, additionally and simultaneously, to consumers that those goods come from a single undertaking under the control of which the goods are manufactured and which is responsible for their quality. …””

239. The legal principles are usefully and comprehensively set out in W3 [229-236]:

“In order to establish infringement under Article 9(1)(b) of the Regulation, six conditions must be satisfied: (i) there must be use of a sign by a third party within the relevant territory; (ii) the use must be in the course of trade; (iii) it must be without the consent of the proprietor of the trade mark; (iv) it must be of a sign which is at least similar to the trade mark; (v) it must be in relation to goods or services which are at least similar to those for which the trade mark is registered; and (vi) it must give rise to a likelihood of confusion on the part of the public. In the present case, there is no issue as to conditions (i)-(iv).

Comparison of services. In considering whether services are similar to each other, all relevant factors relating to the services must be considered, including their nature, their end users, their method of use and whether they are in competition with each other or are complementary: see Case C-106/03 Canon KKK v Metro Goldwyn Mayer Inc [1998] ECR I-5507 at [23].

Likelihood of confusion. The manner in which the requirement of a likelihood of confusion in Article 9(1)(b) of the Regulation and Article 5(1)(b) of the Directive, and the corresponding provisions concerning relative grounds of objection to registration in both the Directive and the Regulation, should be interpreted and applied has been considered by the CJEU in a large number of decisions. The Trade Marks Registry has adopted a standard summary of the principles established by these authorities for use in the registration context. The current version of this summary, which takes into account the decision of the Court of Appeal in Maier v ASOS plc [2015] EWCA Civ 220, [2015] FSR 20, is as follows:

"(a) the likelihood of confusion must be appreciated globally, taking account of all relevant factors;

(b) the matter must be judged through the eyes of the average consumer of the goods or services in question, who is deemed to be reasonably well informed and reasonably circumspect and observant, but who rarely has the chance to make direct comparisons between marks and must instead rely upon the imperfect picture of them he has kept in his mind, and whose attention varies according to the category of goods or services in question;

(c) the average consumer normally perceives a mark as a whole and does not proceed to analyse its various details;

(d) the visual, aural and conceptual similarities of the marks must normally be assessed by reference to the overall impressions created by the marks bearing in mind their distinctive and dominant components, but it is only when all other components of a complex mark are negligible that it is permissible to make the comparison solely on the basis of the dominant elements;

(e) nevertheless, the overall impression conveyed to the public by a composite trade mark may, in certain circumstances, be dominated by one or more of its components;

(f) and beyond the usual case, where the overall impression created by a mark depends heavily on the dominant features of the mark, it is quite possible that in a particular case an element corresponding to an earlier trade mark may retain an independent distinctive role in a composite mark, without necessarily constituting a dominant element of that mark;

(g) a lesser degree of similarity between the goods or services may be offset by a greater degree of similarity between the marks, and vice versa;

(h) there is a greater likelihood of confusion where the earlier mark has a highly distinctive character, either per se or because of the use that has been made of it;

(i) mere association, in the strict sense that the later mark brings the earlier mark to mind, is not sufficient;

(j) the reputation of a mark does not give grounds for presuming a likelihood of confusion simply because of a likelihood of association in the strict sense; and

(k) if the association between the marks creates a risk that the public might believe that the respective goods or services come from the same or economically-linked undertakings, there is a likelihood of confusion."

The same principles are applicable when considering infringement, although as noted above it is necessary for that purpose to consider the actual use of the sign complained of in the context in which it has been used.

Common elements with low distinctiveness. If the only similarity between the trade mark and the sign complained of is a common element that is descriptive or otherwise of low distinctiveness, that points against there being a likelihood of confusion: see Whyte and Mackay Ltd v Origin Wine UK Ltd [2015] EWHC 1271 (Ch), [2015] FSR 33 at [43]-[44].

Family of marks. Where it is shown that the trade mark proprietor has used a "family" of trade marks with a common feature, and a third party uses a sign which shares that common feature, this can support the existence of a likelihood of confusion. As the Court of First Instance (as it then was) explained in Case T-287/06 Miguel Torres v Office for Harmonisation in the Internal Market [2008] ECR II-3817:

"79. As regards the applicant's argument that its earlier marks constitute a 'family of marks' or a 'series of marks', which can increase the likelihood of confusion with the mark applied for, such a possibility was recognised in BAINBRIDGE and confirmed in Case C-234/06 P Il Ponte Finanziaria [2007] ECR I-7333.

80. According to that case-law, there can be said to be a 'series or a 'family' of marks when either those earlier marks reproduce in full the same distinctive element with the addition of a graphic or word element differentiating them from one another, or when they are characterised by the repetition of the same prefix or suffix taken from an original mark (BAINBRIDGE, paragraph 123). In such circumstances, a likelihood of confusion may be created by the possibility of association between the trade mark applied for and the earlier marks forming part of the series where the trade mark applied for displays such similarities to those marks as might lead the consumer to believe that it forms part of that same series and therefore that the goods covered by it have the same commercial origin as those covered by the earlier marks, or a related origin. Such a likelihood of association between the trade mark applied for and the earlier marks in a series, which could give rise to confusion as to the commercial origin of the goods identified by the signs at issue, may exist even where the comparison between the trade mark applied for and the earlier marks, each taken individually, does not prove the existence of a likelihood of direct confusion (BAINBRIDGE, paragraph 124). When there is a 'family' or a 'series' of trade marks, the likelihood of confusion results more specifically from the possibility that the consumer may be mistaken as to the provenance or origin of goods or services covered by the trade mark applied for and considers erroneously that that trade mark is part of that family or series of marks (Il Ponte Finanziaria, paragraph 63).

81. However, according to the above case-law, the likelihood of confusion attaching to the existence of a family of earlier marks can be pleaded only if both of two conditions are satisfied. First, the earlier marks forming part of the 'family' or 'series' must be present on the market. Secondly, the trade mark applied for must not only be similar to the marks belonging to the series, but also display characteristics capable of associating it with the series. That might not be the case, for example, where the element common to the earlier serial marks is used in the trade mark applied for either in a different position from that in which it usually appears in the marks belonging to the series or with a different semantic content (BAINBRIDGE, paragraphs 125 to 127)."

I do not understand it to be in dispute that it is not necessary for this purpose for all of the trade marks in the family to have been registered at the relevant date, provided that at least one was registered and a number were in use.

Colour. Where the trade mark proprietor has used the trade mark in a particular colour or combination of colours, and a third party uses a sign in the same colour or combination of colours, this can support the existence of a likelihood of confusion even if the trade mark is not registered in colour. The CJEU ruled in Specsavers (CJEU) that:

‘Article 9(1)(b) and (c) of Regulation No 207/2009 must be interpreted as meaning that where a Community trade mark is not registered in colour, but the proprietor has used it extensively in a particular colour or combination of colours with the result that it has become associated in the mind of a significant portion of the public with that colour or combination of colours, the colour or colours which a third party uses in order to represent a sign alleged to infringe that trade mark are relevant in the global assessment of the likelihood of confusion or unfair advantage under that provision.’”

|

easyEverything |

This mark was used on a substantial scale in relation to a chain of internet cafes from 1999 to October 2001, at which point the name changed to easyInternetcafe. There is no evidence of use since then in relation to any goods or services. |

|

easyInternetcafe |

The use started declining when the flagship store on Oxford Street was sold in June 2004.

There was no remaining business to speak of by 2009. Ultimately it was a commercial disaster - the company was liquidated in 2016, having lost its shareholders £92m. |

|

easyValue |

An online price comparison site was operated under this name from 2001 to around 2004. Again, it was not a success. Its annual turnover figures were in the low £10s of thousands and it lost over £1m for 3 years in a row. |

|

easyMoney |

A credit card business was set up under this name in 2001 but was short-lived. The trading company (Easymoney (UK) Ltd) appears to have stopped trading in 2003. |

|

easyCruise |

This operated cruises from around 2005 until a date that is unclear, but at some point before 2013. |

|

easyKiosk |

This was used in relation to catering and retail services provided on easyJet flights from around the launch of the airline in 1995. It is the name of the food and drink trolley service and is also used in an onboard catalogue containing details of goods available for purchase onboard. It appears from easyGroup’s disclosure that the use of the name onboard was phased out in around 2007.

This mark has not been used outside the airline. |

|

easyRider |

This was the name of the easyJet inflight magazine from around 1997. It appears that easyJet had stopped using this name by January 2002, when the relatively newly floated easyJet Plc rebranded the inflight magazine as easyJet. |

|

easyRamp |

easyGroup alleges that ground handling services were provided in connection with easyJet flights under this name from 1998/1999.

There is no evidence of consumer-facing use of this name. |

|

easyTech |

This appears to have been used by a company called FLS Aeropsace in relation to the maintenance of easyJet’s aircraft from 1998/1999. The only customer was easyJet and again, this was not a consumer-facing business. |

|

easyHotel |

The first easyHotel was opened in Kensington, London on 1 August 2005. A number of other hotels followed in the UK and it subsequently developed into a substantial business.

easyGroup has claimed that this mark had a reputation from 2006. |

|

easyRentacar |

This was a car rental business that was launched in April 2000, initially from premises in London Bridge. It was a substantial concern. The name changed to easyCar in around 2003. As with easyEverything / easyInternetcafé, this business was never profitable, lost huge sums of money for the shareholders in the relevant period and was discontinued in the mid-late 2000s. |

|

easyCar |

Ms Luxton’s evidence is that easyCar is now a third party agent / booking platform. |

260. It is worth repeating the evidence of Mrs Hall under cross examination:

Q. Did you look at another e-mail from Easylife Group or was it that you just looked more closely at the invoice of the first e-mail?

A. I looked more closely. I think it had been a bit of a fraught day and I had scanned the order confirmation e-mail from them rather too quickly and I missed the column which did actually give a delivery date, but that date had now elapsed by about so many days so I thought I would get in contact with them to say I knew the date, now I had found it, but it had elapsed anyway.

Q. Very clear. When you made your statement, did anyone ask you, in the run-up to preparing your statement, about the e-mail or the materials from Easylife Group that you had been looking at, and looking at first quickly and then more in detail, before sending that second e-mail saying, "Dear easyGroup" I am sorry, that is a very long question. A. Yes, could you just repeat the first part again? Did I look again at the confirmation order e-mail, are you saying?

Q. What I am saying -- and his Lordship will be smiling and saying it is my own fault for asking a silly question, but there you are -- what I am trying to work out, and what is important to us for these proceedings, is what you saw when, who has said what to you when, and what e-mails you got when, because we are trying to work out your thought processes at very stage of your correspondence here; okay?

A. Right. If I believe I am answering the right question ----

Q. I have not asked it yet ----

A. The solicitor was not aware of my original order confirmation e-mail.

Q. Right. So when the solicitor, Mr. Clay, sent you his e-mail 8 on 10th March ----

A. Yes.

Q. ---- and it set out the "Dear easyGroup" bit in the body of that, that is on pages 1 and 2 of the clip of stuff we provided you with.

A. Yes.

Q. He then included the questionnaire?

A. Yes, that is right.

Q. When you answered that, he did not know about the earlier e-mail, did he?

A. No, he did not.

Q. He did not ask you to think about what you were looking at when you sent the later e-mail, did he?

A. No, he just wanted an explanation for my use of easyGroup in that second e-mail.

Q. Yes. I just want to say, having looked at those two e-mails, as we have, the first one and then the second one, and given they were only six minutes apart, I would suggest that the reason you said "easyGroup" rather than “Easylife Group” was probably just an abbreviation from Easylife Group, which you had looked at on the first e-mail, to easyGroup; is that fair?

A. Well, I knew that there was a lite or an easy -- it was either Easylife or Easylite. I could not remember exactly. I was too tired -- it was late in the evening -- to go and determine which it actually was so I just termed it "easyGroup", not knowing that it would lead to this…I can specifically remember thinking, "Was it Easylife or lite?” and thinking “oh, who cares” and putting “group” instead as a sort of a term at the end. I could have put “easycompany”. It was just what came into my head late at night, at the end of a long day. I did not bother to check…”

282. easyGroup have to demonstrate to the satisfaction of the court that easylife has deceived. This is explained by the same Judge who provided judgments in Sky TV and W3 after elevation to the Court of Appeal in Glaxo Wellcome v Sandoz [2019] EWHC 2545 (Ch) by reference to an earlier decision of Jacob J:

“158 As Jacob J forcefully stated in Hodgkinson & Corby Ltd v Wards Mobility Services Ltd [1994] 1 WLR 1564 at 1569-1570:

“I turn to consider the law and begin by identifying what is not the law. There is no tort of copying. There is no tort of taking a man's market or customers. Neither the market nor the customers are the plaintiff's to own. There is no tort of making use of another's goodwill as such. There is no tort of competition. …

At the heart of passing off lies deception or its likelihood, deception of the ultimate consumer in particular. Over the years passing off has developed from the classic case of the defendant selling his goods as and for those of the plaintiff to cover other kinds of deception, e.g. that the defendant's goods are the same as those of the plaintiff when they are not, e.g. Combe International Ltd v. Scholl (UK) Ltd [1980] R.P.C. 1; or that the defendant's goods are the same as goods sold by a class of persons of which the plaintiff is a member when they are not, e.g. Erven Warnink Besloten Vennootschap v. J. Townend & Sons (Hull) Ltd [1979] A.C. 29 (the Advocaat case). Never has the tort shown even a slight tendency to stray beyond cases of deception. Were it to do so it would enter the field of honest competition, declared unlawful for some reason other than deceptiveness. Why there should be any such reason I cannot imagine. It would serve only to stifle competition.

The foundation of the plaintiff's case here must therefore lie in deception…”

159. It is not enough if members of the public are merely caused to wonder. As Jacob LJ explained in Phones 4U Ltd v Phone4U.co.uk Internet Ltd [2006] EWCA Civ 244, [2007] RPC 5:

“16. The next point of passing off law to consider is misrepresentation. Sometimes a distinction is drawn between ‘mere confusion’ which is not enough, and ‘deception’, which is. I described the difference as ‘elusive’ in Reed Executive Plc v Reed Business Information Ltd [2004] RPC 40. I said this, [111]:

‘Once the position strays into misleading a substantial number of people (going from ‘I wonder if there is a connection’ to ‘I assume there is a connection’) there will be passing off, whether the use is as a business name or a trade mark on goods.’

17. This of course is a question of degree—there will be some mere wonderers and some assumers—there will normally (see below) be passing off if there is a substantial number of the latter even if there is also a substantial number of the former.

18. The current (2005) edition of Kerly contains a discussion of the distinction at paras 15–043 to 15–045. It is suggested that:

‘The real distinction between mere confusion and deception lies in their causative effects. Mere confusion has no causative effect (other than to confuse lawyers and their clients) whereas, if in answer to the question: “what moves the public to buy?”, the insignia complained of is identified, then it is a case of deception.’

19. Although correct as far as it goes, I do not endorse that as a complete statement of the position. Clearly if the public are induced to buy by mistaking the insignia of B for that which they know to be that of A, there is deception. But there are other cases too—for instance those in the Buttercup case. A more complete test would be whether what is said to be deception rather than mere confusion is really likely to be damaging to the claimant's goodwill or divert trade from him. I emphasise the word ‘really’.”

160. In order for there to be passing off, a substantial number of members of the public must be misled: see Neutrogena Corp v Golden Ltd [1996] RPC 473 at 493-494 (Morritt LJ). Furthermore, it is not enough that careless or indifferent people may be led into error: see Norman Kark Publications Ltd v Odhams Press Ltd [1962] 1 WLR 380 at 383 (Wilberforce J).

161. The correct approach to this question was well described by Jacob J at first instance in Neutrogena at 482:

“The judge must consider the evidence adduced and use his own common sense and his own opinion as to the likelihood of deception. It is an overall ‘jury’ assessment involving a combination of all these factors, see ‘GE’ Trade Mark [1973] R.P.C. 297 at page 321. Ultimately the question is one for the court, not for the witnesses. It follows that if the judge's own opinion is that the case is marginal, one where he cannot be sure whether there is a likelihood of sufficient deception, the case will fail in the absence of enough evidence of the likelihood of deception. But if that opinion of the judge is supplemented by such evidence then it will succeed. And even if one's own opinion is that deception is unlikely though possible, convincing evidence of deception will carry the day. The Jif lemon case (Reckitt & Colman Products Ltd. v. Borden Inc. [1990] RPC 341) is a recent example where overwhelming evidence of deception had that effect. It was certainly my experience in practice that my own view as to the likelihood of deception was not always reliable. As I grew more experienced I said more and more ‘it depends on the evidence.’”

283. Millett LJ (as he was) helped illuminate the test in Harrods Ltd v Harrodian School Ltd [1996] RPC 697, where he said [714]:

“The absence of a common field of activity, therefore, is not fatal; but it is not irrelevant either. In deciding whether there is a likelihood of confusion, it is an important and highly relevant consideration

“...whether there is any kind of association, or could be in the minds of the public any kind of association, between the field of activities of the plaintiff and the field of activities of the defendant”:

Annabel's (Berkeley Square) Ltd. v. G. Schock (trading as Annabel S Escort Agency) [l9721 R.P.C. 838 at page 844 per Russell L.J.

In [Lego System A/S v. Lego M. Lemelstrich Ltd. [1983] FSR 15] Falconer J. likewise held that the proximity of the defendant's field of activity to that of the plaintiff was a factor to be taken into account when deciding whether the defendant's conduct would cause the necessary confusion.

Where the plaintiff's business name is a household name the degree of overlap between the fields of activity of the parties’ respective businesses may often be a less important consideration in assessing whether there is likely to be confusion, but in my opinion it is always a relevant factor to be taken into account.

Where there is no or only a tenuous degree of overlap between the parties’ respective fields of activity the burden of proving the likelihood of confusion and resulting damage is a heavy one. In Stringfellow v. McCain Foods (G.B.) Ltd. [1984] R.P.C. 501 Slade L.J. said (at page 535) that the further removed from one another the respective fields of activities, the less likely was it that any member of the public could reasonably be confused into thinking that the one business was connected with the other; and he added (at page 545) that:

“even if it considers that there is a limited risk of confusion of this nature, the court should not, in my opinion, readily infer the likelihood of resulting damage to the plaintiffs as against an innocent defendant in a completely different line of business. In such a case the onus falling on plaintiffs to show that damage to their business reputation is in truth likely to ensue and to cause them more than minimal loss is in my opinion a heavy one.”