B e f o r e :

MR JUSTICE JACOBS

____________________

Between:

| |

(1) G.I. GLOBINVESTMENT LIMITED

(2) MATTEO CORDERO DI MONTEZEMOLO

(3) LUCA CORDERO DI MONTEZEMOLO

|

Claimants

|

| |

- and -

|

|

| |

(1) XY ERS UK LIMITED

(2) SKEW BASE INVESTMENTS SCA RAIF

(3) SKEW BASE S.A.R.L.

(4) VP FUND SOLUTIONS (LUXEMBOURG) SA

(5) VP FUND SOLUTIONS (LIECHTENSTEIN) AG

(6) TWINKLE CAPITAL SA

(7) DANIELE MIGANI

(8) FEDERICO FALESCHINI

(9) LEADER LOGIC HOLDING AG

(10) LEADER LOGIC AG

|

Defendants

|

____________________

Daniel Saoul KC, Ben Smiley, Gayatri Sarathy & Benjamin Archer (instructed by Milberg London LLP) for the Claimants

Adam Cloherty KC, James Fennemore & Devon Airey (instructed by Bird & Bird LLP) for the 1st, 6th, 7th, 9th & 10th Defendants.

Robert Weekes K.C. & Warren Fitt (instructed by Forsters LLP) for the 2nd & 3rd Defendants.

Richard Blakeley KC & Camilla Cockerill (instructed by Gresham Legal Limited) for the 4th & 5th Defendants.

Philip Ahlquist (instructed by Enyo Law LLP) for the 8th Defendant.

Hearing dates: 7-10, 14-17, 21-25, 28-31 October, 1, 4-8 November, 2-6 December 2024

Draft judgment circulated 17 March 2025

____________________

HTML VERSION OF APPROVED JUDGMENT�

____________________

Crown Copyright ©

This judgment was handed down remotely at 10:30am on 28th March 2025 by circulation to the parties or their representatives by e-mail and by release to the National Archives.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

MR JUSTICE JACOBS:

TABLE OF CONTENTS (by paragraph number)

| A: |

Introduction |

1 |

| A1: |

The claims in outline |

1 |

| A2: |

The Claimants |

8 |

| A3: |

The Defendants |

17 |

| A4: |

Outline narrative |

32 |

| A5: |

Scheme of this judgment |

73 |

| B: |

Approach to the evidence and the witnesses |

85 |

| B1: |

Approach to the evidence |

85 |

| C: |

Approach to the evidence and the witnesses |

149 |

| C1: |

Introduction |

149 |

| C2: |

The MIN products |

153 |

| C3: |

The HFPO Products |

173 |

| D: |

The dealings and meetings between the Claimants and XY |

186 |

| D1: |

Initial meetings in 2016 |

186 |

| D2: |

The 20 September 2016 meeting |

252 |

| D3: |

Late September 2016 – November 2016 |

303 |

| D4: |

December 2016 and the 2 December 2016 video call |

321 |

| D5: |

January 2017 |

349 |

| D6: |

February – March 2017 |

393 |

| D7: |

April – June 2017 |

461 |

| D8: |

July – December 2017 |

512 |

| D9: |

January – February 2018 |

519 |

| D10: |

9 March 2018 meeting and the new liquidity |

545 |

| D11: |

March/April 2018 and the fees correspondence |

571 |

| D12: |

May 2018 - the draft letter and PowerPoint for the di Montezemolo family |

623 |

| D13: |

June – December 2018 |

639 |

| D14: |

2019 |

694 |

| D15: |

January to March 2020 and the Covid-19 pandemic |

715 |

| D16: |

April to June 2020 |

740 |

| E: |

The Skew Base Offering Memoranda |

758 |

| E1: |

Introduction |

758 |

| E2: |

The main body of the Offering Memoranda |

783 |

| E3: |

The HFPO Compartment Appendix |

784 |

| E4: |

The MIN (EUR) compartment |

785 |

| F: |

The origins and operation of the Skew Base Fund |

788 |

| F1: |

Luxembourg investment funds |

788 |

| F2: |

Events leading to the creation of the Skew Base Fund and the Offering Memoranda |

805 |

| F3: |

The contractual agreements |

838 |

| F4: |

The witness evidence concerning the operation of the Skew Base Fund |

845 |

| F5: |

The evidence of Mr Konrad |

849 |

| F6: |

The evidence of Mr Ben Kone |

894 |

| F7: |

Mr Ries' evidence |

902 |

| F8: |

Mr von Kymmel's evidence |

918 |

| F9: |

Ms Gaveni's e-mails concerning Twinkle |

929 |

| F10: |

The work of the General Partner (SB GP) |

938 |

| F11: |

The "Connections" between XY/Mr Migani and the Skew Base Fund |

962 |

| G: |

The claim in deceit concerning the "Investment Representations" |

969 |

| G1: |

Deceit – legal principles |

969 |

| G2: |

The case on "Investment Representations" pleaded in the Re-Amended Particulars of Claim |

1001 |

| G3: |

The parties' arguments |

1013 |

| G4: |

Discussion |

1029 |

| H. |

The claim in deceit concerning the "Independence Representations" |

1140 |

| H1: |

The key issues |

1140 |

| H2: |

What representations were made and were they continuing? |

1148 |

| H3: |

Was the representation false? |

1154 |

| H4: |

The central factual issue: the parties' arguments |

1158 |

| H5: |

The central factual issue: discussion |

1173 |

| H6: |

Conclusion on the investment misrepresentation claim |

1229 |

| I: |

Fiduciary duty and dishonest assistance |

1236 |

| I1: |

Summary of principal arguments |

1236 |

| I2: |

Discussion |

1238 |

| J: |

Unlawful Means Conspiracy |

1259 |

| J1: |

Legal Principles |

1259 |

| J2: |

The parties' arguments |

1271 |

| J3: |

Discussion |

1278 |

| K: |

The non-fraud claims |

1300 |

| K1: |

Overview |

1300 |

| K2: |

The COBS rules |

1307 |

| K3: |

Breach of express terms |

1314 |

| K4: |

The claim for breach of implied terms and a duty of care in tort |

1328 |

| K5: |

The claim under FSMA s. 138D |

1390 |

| L: |

XY's counterclaim |

1406 |

| M: |

Conclusion |

1410 |

A: Introduction

A1: The claims in outline

- The Claimants bring claims against 10 Defendants arising out of substantial losses made on investments which proved disastrous when the Covid-19 pandemic hit in 2020 and financial markets suffered severe falls.

- The Claimants contend that these loss-making investments were made on the advice of the First Defendant, XY ERS UK Ltd ("XY"). (Appendix 1 contains a list of the main abbreviations used in this judgment). XY is an English company which was then, but is now no longer, authorised by the Financial Conduct Authority, to carry out regulated activities. It is part of a corporate group which operates in various European countries and was founded, and is owned by, its Chief Executive Officer, Mr Daniele Migani ("Mr Migani"). Mr Migani is the Seventh Defendant in these proceedings.

- The Claimants allege that they are the victims of a substantial fraud perpetrated by XY, Mr Migani and a colleague with whom he worked closely, Mr Federico Faleschini ("Mr Faleschini" – the Eighth Defendant). They allege that the fraud was carried out with the assistance and complicity of other Defendants. Those other Defendants comprise a series of companies which are alleged to have been controlled or influenced by Mr Migani and Mr Faleschini. Those companies are the Second, Third, Sixth, Ninth and Tenth Defendants.

- The two remaining Defendants, also alleged to have assisted and been complicit in the alleged fraud, are independent of Mr Migani and Mr Faleschini. They are the Fourth Defendant, VP Fund Solutions Luxembourg SA ("VP Lux"), and the Fifth Defendant, VP Fund Solutions (Liechtenstein) ("VP Liechtenstein"). These companies form part of a banking and financial services group of companies with its head office in Liechtenstein. The group includes a bank, VP Bank AG ("VP Bank"). Where it is not necessary to distinguish between the various companies in the group, I will simply refer to "VP".

- In summary, the Claimants allege that they retained XY to provide them with financial advice on their investment portfolio. They say that XY presented itself as an independent, unbiased and conflict-free advisor[1], and was engaged on that basis. Thereafter, over a substantial period of time, XY recommended that the Claimants invest in various financial products, consistent with what they understood to be XY's business model. They also allege that those investments were held out as being in line with the Claimants' clearly expressed investment objectives: in summary, capital preservation, liquidity and returns of around 3% per annum, consistent with a conservative approach. (I shall refer to the Claimants' pleaded investment objectives as the "Investment Objectives"). They bring claims in fraud against XY, Mr Migani and Mr Faleschini. They bring claims in conspiracy against all of the Defendants. They also bring claims (i) for breach of fiduciary duty against XY; (ii) against Mr Migani for dishonestly assisting the breach of fiduciary duty; and (iii) against XY for breach of various contractual tortious and regulatory duties.

- All of these claims are denied by all of the Defendants. Opening submissions and the evidence at trial took place over 23 days, with a large number of witnesses giving evidence. Closing submissions took place over a further 5 days. The trial was conducted with great skill and courtesy by all counsel. Mr Saoul KC presented the case for the Claimants. Mr Cloherty KC acted for Mr Migani and XY, and three other companies which, directly or indirectly, Mr Migani owned: namely the Sixth, Ninth and Tenth Defendants. Mr Weekes KC presented the case for the Second and Third Defendants, and Mr Ahlquist presented the case for Mr Faleschini. Mr Blakeley KC presented the case for VP Lux and VP Liechtenstein. All leading counsel were clearly greatly assisted both by their juniors (most of whom carried out some examination or cross-examination of witnesses) and their solicitor teams. The submissions overall were of the highest quality.

- At a case management conference, the parties were ordered to seek to agree a factual narrative. They were ultimately able to agree, in chronological narrative form, a list of uncontentious facts relevant to the issues in dispute. The following description of the parties is taken, principally, from that narrative. Where the narrative indicated that there was common ground between the parties as to what occurred at meetings, I have incorporated that common ground into Section D, where I deal with the meetings in detail.

A2: The Claimants

- The First Claimant, G. I. Globinvestment Limited ("GIG"), is an English company incorporated on 8 June 2016, which is used by the di Montezemolo family to make and hold certain investments, including those which are the subject of this claim. The Second Claimant, Matteo Cordero di Montezemolo ("MDM"), and the Third Claimant, Luca Cordero di Montezemolo ("LDM"), are both high net worth individual members of the di Montezemolo family. MDM is LDM's son. Both MDM and LDM are Italian citizens, and LDM is a well-known industrial figure in Italy, principally as a result of his leadership of Ferrari described below. Although MDM is Italian, he was resident in England during 2016 – 2020, which is the period central to the claim.

- MDM has a degree in economics from Bologna University. In addition, MDM is or has been: (i) Co-founder, chairman of the board, CEO, and member of the investment committee of Charme Capital Partners SGR SpA ("Charme"). Charme manages private equity investment funds with more than € 1 billion under management; (ii) a member of the board of Banca Intermobiliare di Investimenti Gestioni SpA, a major Italian private/wealth management bank; (iii) a member of the board of Santander Private Banking SpA – a major Italian private/wealth management bank (and part of the well-known multi-national Santander banking group); and (iv) a member of the board of other major Italian corporations, including Octo Telematics SpA, a multinational technology company, and Poltrona Frau and Cassina SpA (both luxury furniture companies).

- MDM is a person with considerable financial expertise and business experience. After university, he worked for Goldman Sachs in their investment banking team. He then founded Charme with his father. Charme has established four private equity funds, known as Charme I, II, III and IV. They are all classified as alternative investment funds or "AIFs" for the purposes of the EU Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive. Charme I was established in 2003 and ran to 2014. Charme II was established in 2009 and ran to 2016. Charme III and IV were established in 2015 and 2021 respectively, and are still running. The overall capital raised by the funds is around USD 2 billion. The basic idea of these private equity funds was to identify presently undervalued companies so that their potential could be unlocked for the benefit of investors.

- MDM kept his personal wealth separate from that part of the wealth of the di Montezemolo family which was held by GIG. MDM's wealth was in part held by an Italian company Emmediemme Tre SRL ("SRL"), which initially made some of the investments relevant to these proceedings. He had "resident but non-domiciled" tax status in the United Kingdom from 3 September 2015 until 2023 when he moved back to Italy.

- LDM, who graduated with a master's degree in international commercial law from Columbia University, is a prominent Italian businessman. By way of example, for more than 20 years LDM was Chairman of Ferrari, the well-known luxury sports car manufacturer and leading Formula 1 team. He referred in his evidence to having won 19 world championships. He is or has also been: (i) Co-founder and chairman of Charme; (ii) Co-founder, chairman of Nuovo Trasporto Viaggiatori SpA, the largest private train operating company in Italy; (iii) Chairman and CEO of Fiat SpA; (iv) Chairman of Manifatture Sigaro Toscano SpA; (v) Vice-chairman of the board of UniCredit SpA, the second largest bank in Italy (and one of the largest banks in the EU); (vi) Chairman of the board of Alitalia, the flag carrier of, and largest airline in, Italy; and (vii) President of Confindustria (the General Confederation of Italian Industry).

- According to its most recently filed accounts, the net assets of GIG amount to €212 million.

- MDM and Marco Nuzzo were appointed as directors of GIG on 8 June 2016. MDM resigned on 26 June 2018, since which date Mr Nuzzo has been its sole director. Mr Nuzzo is the longstanding trusted advisor to, and agent of, LDM and the di Montezemolo family in relation to their investment assets. He has a power of attorney over LDM's private accounts and personal financial investments and is a member of the board of a number of companies owned directly or indirectly by LDM and MDM (or by family trusts), including GIG. Mr Nuzzo's function at GIG was, and is, to represent the interests of the di Montezemolo family.

- For most of the material time:

(i) GIG was owned as to 100,099 Class A Ordinary Shares by Withers Trust Corporation Limited as trustee of the "B Trust", an irrevocable discretionary trust established by LDM for the benefit of his five sons (including MDM), and as to one Class B Ordinary Share (with special voting rights) by MDM personally.

(ii) The Class A shares were subsequently transferred to Gamma Holdings Sarl, of which Mr Nuzzo is a director and which is controlled as to 28% by MDM and as to 72% by Withers Trust Corporation Limited (continuing to hold those shares as trustee of the B Trust).

- Mr Nuzzo, MDM and LDM all gave evidence at the trial.

A3: The Defendants

- The First Defendant, XY, is a company incorporated in England and Wales. It is part of the XY Group, which includes XY as well as XY SA, a company incorporated in Switzerland. XY SA is the holding company for the XY Group and has its head office in Zurich.

- The XY Group provides data technology and strategy consultancy services to those managing high-end wealth. Its services include wealth management, advising on and making arrangements for investments. XY (formerly as the regulated entity within the XY Group) only provided those services to "professional clients" and "eligible counterparties", within the meaning of the Markets in Financial Instruments Directives 2014 and 2018 ("MiFID"), and was authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority ("FCA") to do so. XY's FCA authorisation was cancelled on 22 February 2024, and it is no longer authorised to provide regulated activities and products in the UK.

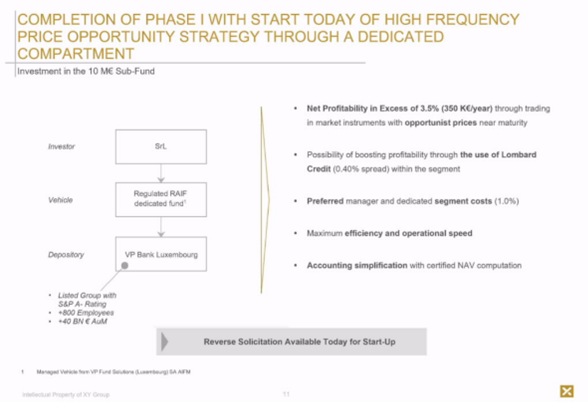

- The Second Defendant, Skew Base Investments SCA RAIF (the "Skew Base Fund" or "the Fund"), is an investment company with variable share capital incorporated in the form of a partnership limited by shares that was incorporated under Luxembourg law on 9 February 2017. The Skew Base Fund qualified as an AIF within the meaning of the Alternative Investment Fund Managers Directive (2011/61/EU). The Skew Base Fund was set up as an umbrella fund comprising several compartments (a "Compartment" or the "Compartments"), including High Frequency Price Opportunity ("HFPO") and Market Insurance Notes ("MIN") Compartments, as explained below.

- The Third Defendant, Skew Base S.A.R.L. ("SB GP"), is a private limited company that was incorporated under Luxembourg law on 24 November 2016. SB GP was the general partner of the Skew Base Fund from the date of the latter's incorporation.

- The Skew Base Fund was set up by the Sixth Defendant, Twinkle Capital SA ("Twinkle"), with Mr Migani's involvement. Twinkle also had a significant role in the process whereby investments were made by the Skew Base Fund.

- The Fourth Defendant, VP Lux, is part of the VP Bank group, which is headquartered in Liechtenstein. It was at all material times the Alternative Investment Fund Manager ("AIFM") and Administrator of the Skew Base Fund pursuant to (i) an AIF Management Agreement (the "AIFMA"); and (ii) an Administrative Services Agreement (the "ASA") respectively, both between VP Lux and the Skew Base Fund (represented by SB GP) and dated 9 February 2017. Pursuant to the AIFMA, VP Lux agreed (among other things) to act as the external AIFM for the Skew Base Fund, in accordance with Article 4(1) of the Luxembourg law on reserved AIFs and, accordingly, to perform the functions of portfolio management and risk management.

- The Fifth Defendant, VP Liechtenstein, is also part of VP Bank group. Pursuant to an Investment Management Delegation Agreement between VP Lux, VP Liechtenstein and the Skew Base Fund (represented by SB GP), VP Lux delegated the portfolio management function to VP Liechtenstein.

- VP Lux and VP Liechtenstein were remunerated pursuant to their agreements with SB GP and the Skew Base Fund for their roles as AIFM and Investment Manager respectively.

- The Sixth Defendant, Twinkle, is a company incorporated under the laws of Switzerland. It was formerly known as Ziusudra SA until on or about 7 September 2017. Twinkle is the 100% shareholder of SB GP. Twinkle's directors were Antonio Grasso from incorporation until November 2019, and Mr Faleschini from 15 December 2017 until present.

- The Seventh Defendant, Mr Migani, is and was at all material times the CEO and a director of XY. Mr Migani is also the owner of 100% of the shares in Twinkle, which in turn is the 100% owner of SB GP. Mr Migani therefore indirectly owns SB GP. Mr Migani was regulated by the FCA until 22 February 2024 when XY's FCA authorisation was cancelled. Mr Migani is the owner and one of three directors of Leader Logic Holding AG, which wholly owns Leader Logic AG, both introduced below.

- The Eighth Defendant, Mr Faleschini, was at all material times the company secretary of XY, as well as CFO of XY SA and the XY Group. He was also head of XY's software development department, known as LAB. Mr Faleschini has been a director of Twinkle since 15 December 2017.

- The Ninth Defendant, Leader Logic Holding AG ("Leader Logic Holding"), is a private limited company incorporated under the laws of Switzerland. It was known as Leader Logic AG until 16 December 2019. Mr Migani is the owner of 100% of the shares in Leader Logic Holding.

- The Tenth Defendant, Leader Logic AG ("Leader Logic"), is a private limited company incorporated under the laws of Switzerland. Leader Logic Holding is the owner of 100% of the shares in Leader Logic.

- The parties were agreed that: the fact of any directorship held was a matter of public record in either England (with respect to XY), Luxembourg (with respect to SB GP) or Switzerland (with respect to Twinkle, Leader Logic and Leader Logic Holding), as the case may be; the Luxembourg companies register recorded that Skew Base Fund's general management was overseen by its general partner, SB GP (and that SB GP was 100% owned by Twinkle).

- XY classified GIG, MDM, LDM and SRL as "professional clients" for FCA Handbook and MiFID purposes, and they each accepted that classification. SRL was also a "large undertaking" within the meaning of MiFID.

A4: Outline narrative

- This section contains, by way of an overview, an outline narrative of the main events and agreements which have given rise to the litigation. Later sections deal with these events and agreements in greater detail.

2016

- In around April 2016, Mr Migani and LDM were introduced, and arrangements were made for Mr Migani to meet Mr Nuzzo in London. There was an initial meeting in May 2016 and a further meeting in June 2016, both attended by Mr Nuzzo. There was a further meeting in July 2016, following which GIG and XY entered into a written agreement on 18 July 2016. This was the first agreement between the parties ("the First Agreement").

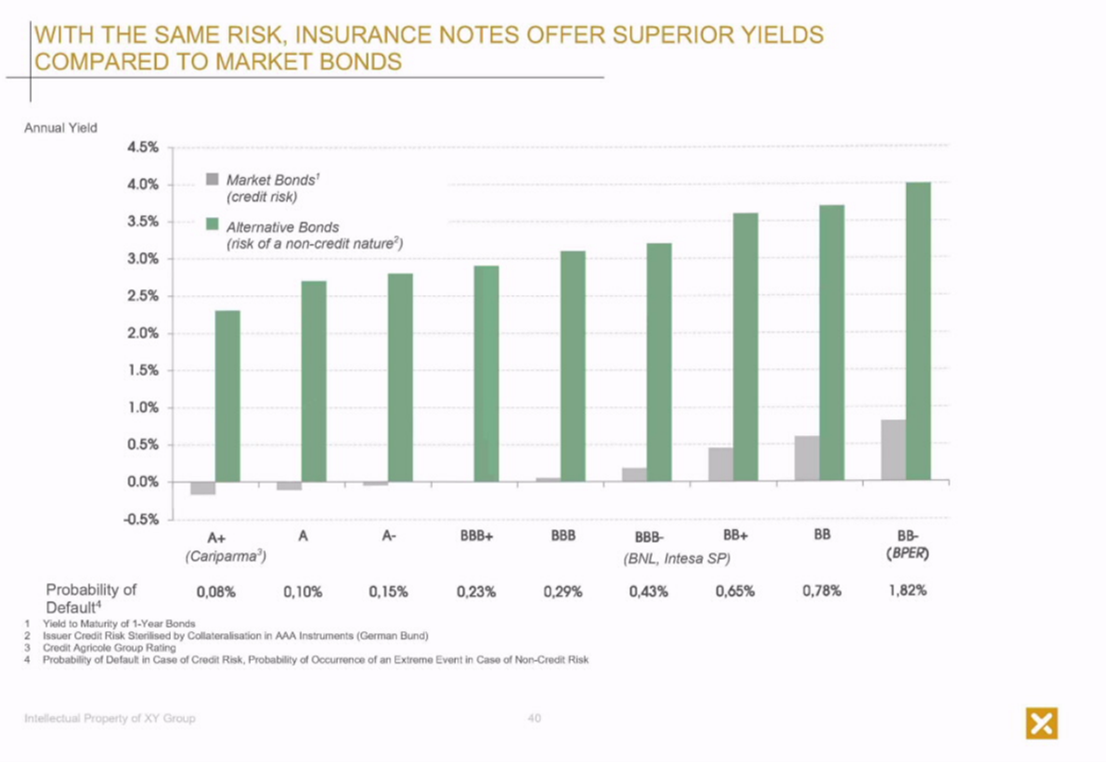

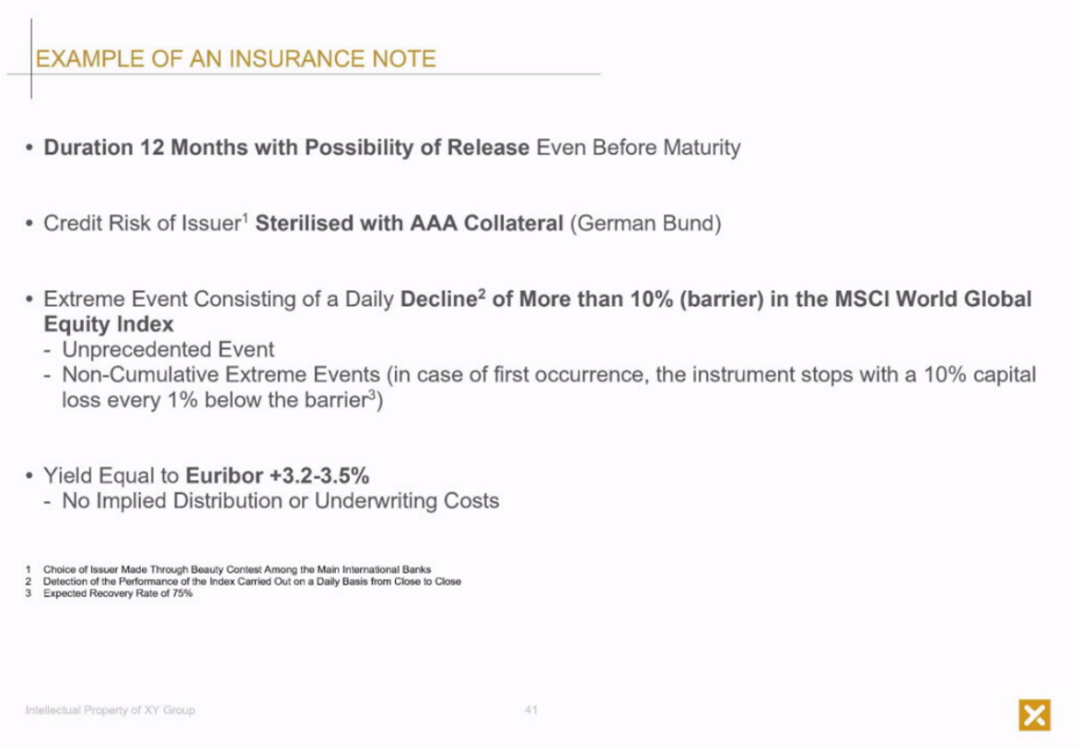

- Following the First Agreement, GIG and LDM provided XY with various information about GIG and LDM's financial positions, and there was a further meeting in September 2016 for which a detailed PowerPoint presentation was prepared. This included slides which related to potential MIN and HFPO investments.

- The September 2016 meeting led to a second agreement dated 21 September 2016 ("the Second Agreement") between XY and GIG. On 21 September 2016, GIG also entered into a separate agreement with XY SA, according to which XY SA provided day-to-day data management and reporting services.

- XY continued to provide services in accordance with the terms of the Second Agreement, until a third agreement between XY and GIG was signed on 1 July 2018 ("the Third Agreement"). The Third Agreement was concluded after very substantial further funds (referred to by the parties as the "new liquidity") had become available to GIG.

- The first meeting after the September 2016 agreement was held on 26 October 2016 and was attended by Mr Nuzzo, MDM and LDM. At this point in time, the parties' discussions had concerned the assets of LDM and the di Montezemolo family companies.

- In December 2016, however, MDM initiated discussions in relation to his personal wealth; assets which he held personally or through SRL. These discussions were not, at the time, revealed to Mr Nuzzo.

2017

- Further meetings with MDM, in relation to his personal wealth, took place in January and March 2017. The possibility of MDM investing in a Luxembourg fund – the fund which became the Skew Base Fund – was first mentioned in a video call in December 2016. It was then further discussed with MDM in early 2017. The first XY PowerPoint presentation which refers to this possible investment was in the presentation for the meeting with MDM on 2 March 2017.

- The agreements which related to the structure and operation of the Skew Base Fund had been concluded on 9 February 2017. These comprised the AIFMA and ASA previously described. On the same date, Twinkle – whilst still at that time named Ziusudra SA – entered into a Service and Technological Agreement ("the STA") with VP Lux and VP Liechtenstein, renewable annually, absent service of a notice of termination, pursuant to which Twinkle undertook to implement, maintain and operate a technological system intended to assist VP Lux and VP Liechtenstein in their performance of the portfolio management function. The schedules to the STA contemplated that Twinkle's services would be provided in respect of 8 different Compartments of the Skew Base Fund, including two in which SRL and GIG later invested (with SRL's investment subsequently being transferred to MDM).

- Also on 9 February 2017, Twinkle entered a Support Service Agreement with SB GP (the "SSA"), terminable without cause upon three months' notice, pursuant to which Twinkle undertook to provide SB GP with services embodied by "assistance in connection to, inter alia, accounting, reporting, marketing, risk, strategic and management support services" as further detailed in the SSA (under clause 5). The schedules to the agreement contemplated Twinkle's services would be provided to SB GP in respect of eleven different investment opportunities and accounts (including the 8 Compartments named in the STA referred to in the previous paragraph).

- In late March 2017, after MDM had signed a "Reverse Solicitation Letter", VP sent him the "Offering Document" relating the HFPO Centaurus Compartment of the Skew Base Fund, together with a subscription form (I shall refer to the Offering Documents, for the various Compartments, as the "Offering Memorandum" or "Offering Memoranda"). The Offering Memorandum contained details of the Fund, and the risks of investing. Following due diligence carried out (principally) by Mr Facoetti in relation to MDM's tax position, and after further meetings between XY, MDM and Mr Facoetti on 28 March 2017 and 25 April 2017, MDM on behalf of SRL signed the subscription form. SRL thereby applied to invest € 10 million in the HFPO Centaurus Compartment of the Fund. The subscription form contained various declarations, including that MDM (on behalf of SRL) had carefully considered the Offering Memorandum in advance of the application, noting especially the investment policy and the risk factors relating thereto.

- The € 10 million investment by SRL was the first of a number of investments which the Claimants (and SRL) made in the Skew Base Fund between May 2017 and December 2019. It was, however, the only investment in the Fund which was made in 2017.

- During the remainder of 2017, there were a number of further meetings between XY and the Claimants. The majority of these meetings related to MDM's personal wealth, but there were also 2 meetings concerning the position of GIG/LDM. In the slide presentations for these meetings, MDM was referred to as "Daddy", and GIG/LDM as "Beauty".

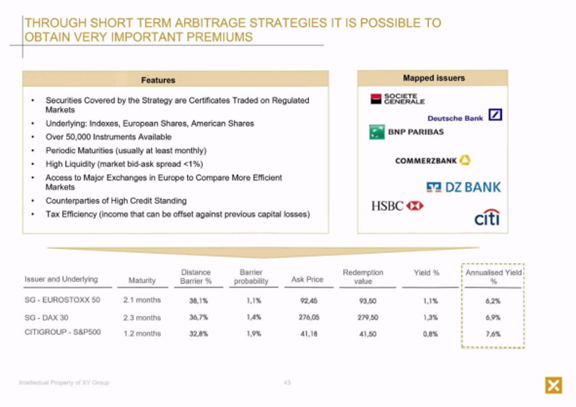

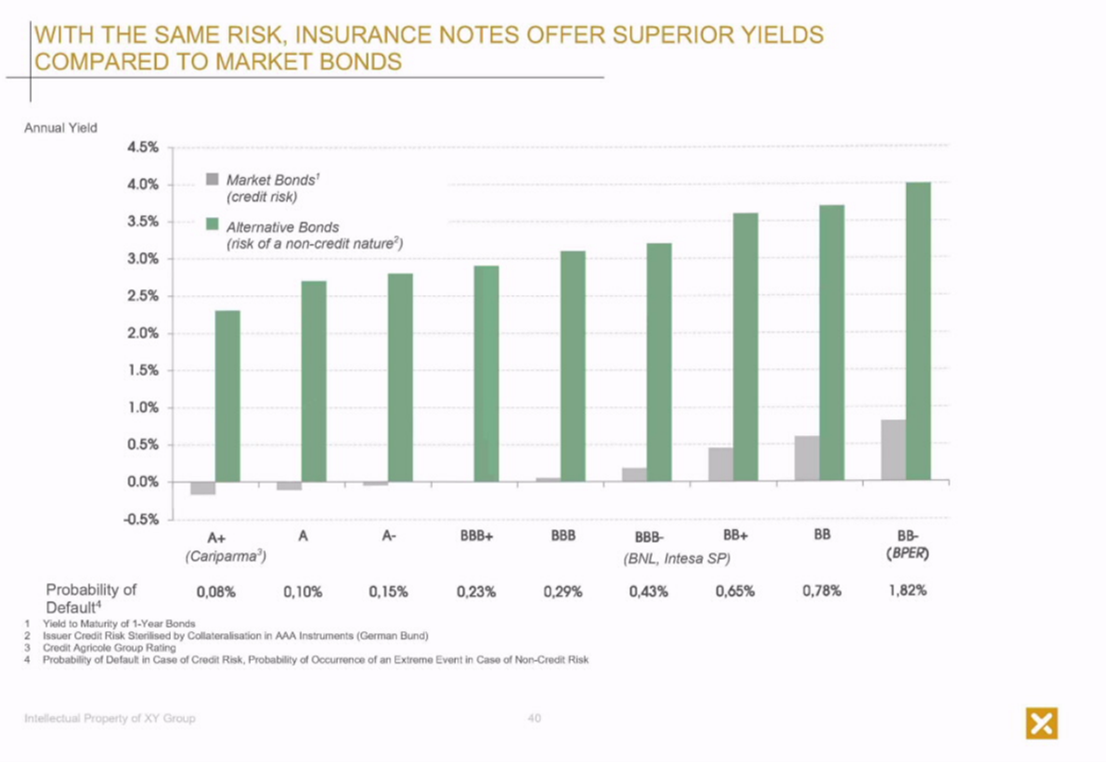

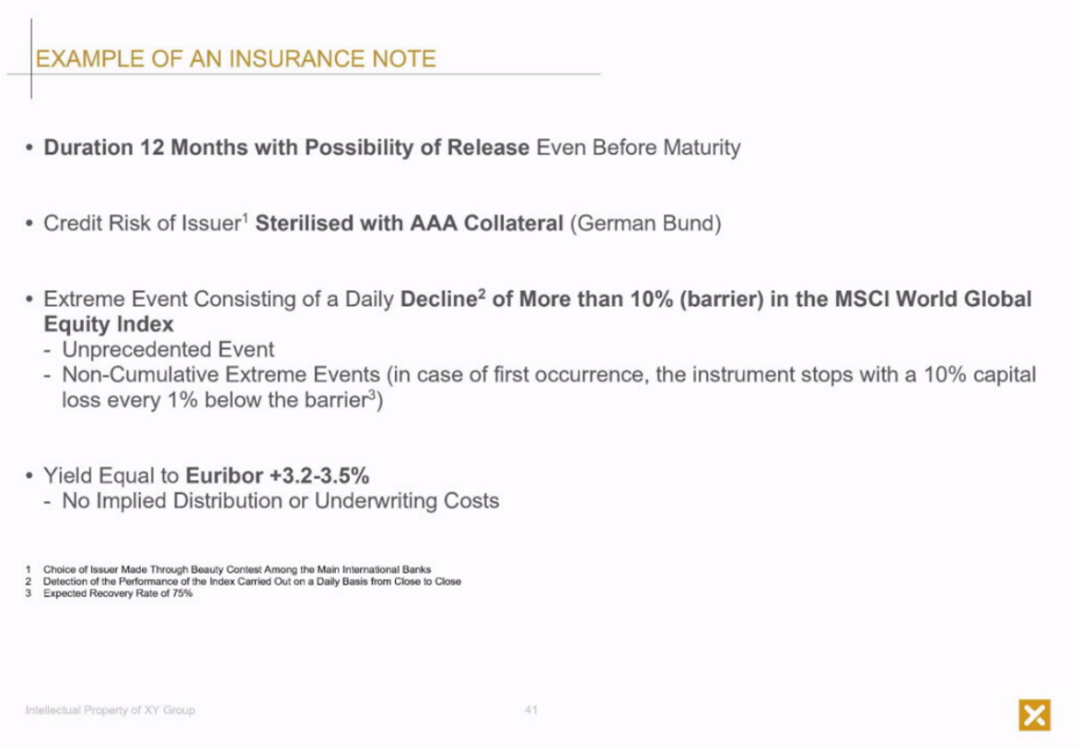

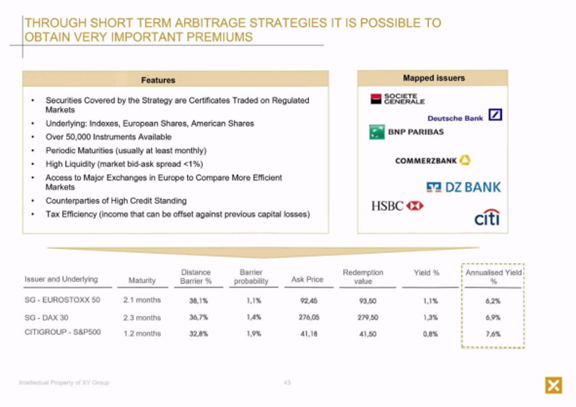

- Also in 2017, beginning in March, investments in MIN and HFPO structured products were made by or on behalf of LDM and GIG (by Mr Nuzzo) and MDM and SRL. These investments were outside the Skew Base Fund, although the Skew Base Fund invested in the same type of products. In the course of 2017, some 47 contracts were concluded. These non-Skew Base Fund investments continued to be made throughout 2018 and 2019. In 2018, there were 68 such investments. The investments were made following a notification sent by XY to either Mr Nuzzo or MDM/Mr Facoetti. XY's witnesses described these notifications of investments as containing a "proposal" which was in accordance with the strategy which had been agreed between the parties. The Claimants contend that these notifications are to be regarded as "advice" or "recommendations" that the investments should be concluded.

- All of these investments made in 2017 and 2018 were profitable, and no claim is advanced in respect of them. The first non-Skew Base Fund investment in respect of which a claim is made was the 121st investment which had been made (in March 2019) following a proposal by XY.

2018

- On 18 February 2018, a second investment in the Skew Base Fund was made. This was an investment of € 3 million in the Skew Base Tangible Credit Compartment. This investment proved profitable, and there is no claim in respect of it.

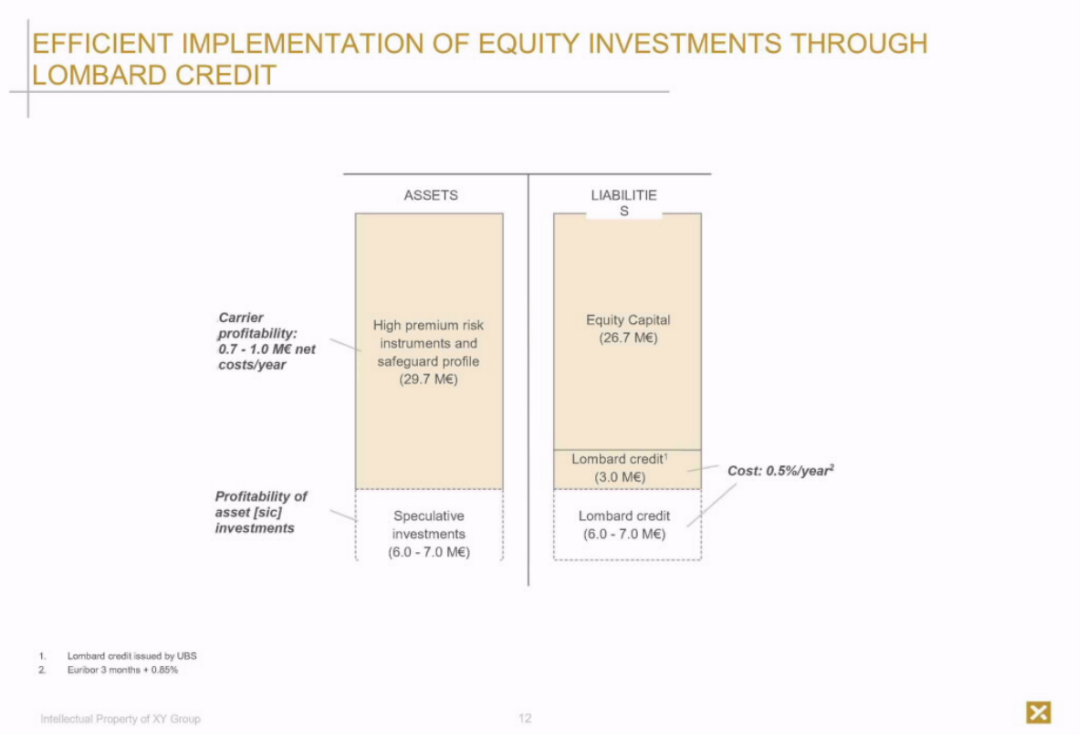

- By early 2018, as a result of a successful equity investment (unconnected to XY), there were substantial further funds (referred to in the evidence as the new liquidity) available to GIG. There was potentially a sum in excess of € 200 million available for further investment. A number of meetings were held in the course of 2018 in relation to the possible investment by GIG. All of these meetings were attended by Mr Nuzzo, and most of them by MDM (who remained a director of GIG until June 2018).

- These meetings led to the Third Agreement between XY and GIG on 1 July 2018, and also to investment by GIG in a number of Skew Base Fund Compartments. In August 2018, VP Lux sent the Offering Memoranda and subscription forms to Mr Nuzzo for 5 Compartments, including the HFPO, MIN (EUR) and MIN USD Compartments. The HFPO and MIN Offering Memoranda were both reviewed by Mr Nuzzo.

- In September 2018, Mr Nuzzo on behalf of GIG completed application forms in relation to the HFPO and MIN (EUR) Compartments. In October 2018, GIG transferred € 27 million to each of those Compartments.

- In late 2018, GIG invested further funds in various Compartments of the Skew Base Fund, as follows: 15 November 2018, € 4,999,999.99 in the Tangible Credit Compartment; 30 November 2018, € 10 million in the Real Estate Compartment, and a further € 3,999,999 in the Tangible Credit Compartment; 4 December 2018, € 5 million in the HFPO Compartment; 7 December 2018, € 5 million in the MIN (EUR) Compartment; 14 December 2018, a further € 5 million in the Tangible Credit Compartment.

- Accordingly, by the end of the 2018, the total amount invested by GIG in various compartments was (in round terms) € 88 million, comprising: HFPO - € 32 million; MIN (EUR) - € 32 million; Tangible Credit - € 14 million; Real Estate - € 10 million.

2019

- During 2019, there were further meetings between XY and the Claimants, and further investments both in the Skew Base Fund and outside it, as well as some redemptions from the Fund.

- In February 2019, in respect of SRL's € 10 million investment in the Skew Base Fund, MDM elected for his entitlement to a dividend to be satisfied by the transfer of the shares in the Skew Base Fund held by SRL to himself, by way of a dividend in specie from SRL.

- In May 2019, GIG redeemed shares with a value of € 8 million in the HFPO Compartment. In June 2019, GIG redeemed shares with a value of € 6.8 million in the MIN (EUR) Compartment.

- In September 2019, MDM invested USD 1,499,990 in the Skew Base MIN (USD) Compartment. This was the last investment made by any of the Claimants in the Skew Base Fund. LDM at no stage invested in the Fund.

- In relation to SB GP, there were two agreements which altered the arrangements which had been made in February 2017.

(1) On 1 October 2019, SB GP and Leader Logic Holding entered into a Support Service Agreement (the "2019 Leader Logic Support Service Agreement"). In summary, under the agreement:

(i) Leader Logic Holding would provide a range of ongoing support services "as from time to time needed by [SB GP]" relating to "Policies and Procedures", "Valuation Methods", "Strategies and Guidelines" and the "Fund's Management" (clause 3);

(ii) There was an initial set-up period of three months from the date of the agreement (clause 9); and

(iii) Leader Logic Holding was entitled to fees calculated as set out in Schedule 1 to the agreement and there was provision for "advance payments".

(2) On 16 January 2020, SB GP and Leader Logic entered into a Support Service Agreement (the "2020 Leader Logic Support Service Agreement").

- SB GP's fees were set out in the Offering Memorandum for each Compartment of the Skew Base Fund into which GIG and SRL and MDM invested. The fees paid to VP Lux, VP Liechtenstein, Twinkle, Leader Logic Holding and/or Leader Logic did not result in any additional costs or fees being paid by GIG and SRL beyond those fees paid to SB GP when making investments into, or continuing to hold investments in, any of the relevant Compartments of the Skew Base Fund.

2020

- On 22 January 2020, a further meeting at XY's offices in London took place between Mr Migani and Mr Dalle Vedove (for XY), Mr Nuzzo and MDM. XY delivered a presentation in which, amongst other things, it was noted:

(i) The value of GIG's assets totalled €343.5m, of which €192.6m was allocated to financial assets;

(ii) The net return produced in 2019 by these financial assets was 3.84%. This resulted in an additional income for GIG of €1.27m;

(iii) In 2019, the SB (EUR) MIN Compartment investment had performed in line with the target return of 3.1%. The SB HFPO investment had outperformed the target return of 3.5% and achieved a net return of 4.8%. The SB (USD) MIN Compartment had also outperformed its target return of 3%, achieving a 7.3% net return.

- This was the last meeting between the parties.

- In February 2020, and particularly March 2020, financial markets were severely impacted by the Covid-19 pandemic. In March 2020, two market indices (the S&P 500 and the Euro Stoxx 50) suffered 1-day falls of greater than 10%. Equity markets were generally falling at around that time.

- On 12 March 2020:

(i) In light of the effect of Covid-19 on the financial markets, Mr Nuzzo e-mailed Mr Dalle Vedove to ask for information regarding the SB HFPO and MIN Compartments.

(ii) Mr Nuzzo also e-mailed VP Lux requesting detailed information about the SB MIN and HFPO Compartments.

(iii) A telephone call took place between Mr Migani, Mr Dalle Vedove, Mr Facoetti and MDM about the status and strategy for MDM's investments given the state of the markets.

- On 13 March 2020, MDM sent Mr Dalle Vedove an e-mail which, in summary, set out questions about the barriers, capital losses and realisable values of various instruments.

- On 13 March 2020, GIG and MDM received e-mails from VP Lux attaching a Notice to Shareholders stating that due to the distressed market conditions in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic, SB GP/Skew Base Fund had decided to suspend the calculation and publication of the NAV (i.e. the Net Asset Value) for the relevant Compartments.

- On 25 March 2020, GIG and MDM received a Notice to Shareholders in respect of the SB HFPO Compartment. In summary, that notice:

(i) Noted that Covid-19 had had a significant impact on the markets, causing the markets to crash and become particularly volatile;

(ii) Noted that the Compartment invested in "financial instruments traded over-the-counter or OTC, which generally tend to be less liquid than instruments that are listed and traded on exchanges";

(iii) Explained that an inability to dispose of assets had resulted in the Compartment being unable to meet a collateral shortfall;

(iv) Confirmed that SB GP, after considering advice from VP Lux, had decided that the collateral shortfall in the Compartment could not be rectified and concluded that the Compartment should be liquidated, and the shares compulsorily redeemed in accordance with the provisions in the Offering Documents and Articles of Association of the Fund.

- On the same date, GIG and MDM received a further Notice to Shareholders in respect of the SB MIN Compartment, which confirmed that SB GP had also decided to liquidate the MIN Compartment and compulsorily redeem the shares. The notice explained that the decision was taken due to the effect of Covid-19 on the market, which, given the nature of the products, had the effect that it would be difficult to achieve the objective of generating a return by investing in those products.

- Both 25 March 2020 notices informed GIG and MDM that their shares in both Compartments would be compulsorily redeemed with effect from the date when calculation of the NAV per share could reasonably be calculated. GIG and MDM would then receive any monies from the liquidation proceeds in proportion to their shareholdings and according to the terms of the Offering Documents.

- Between March and April 2021, GIG and MDM received payments in respect of the redeemed shares in the SB MIN Compartment.

- In broad terms, at the end of the liquidation processes, GIG and MDM's redemptions from the SB HFPO Compartment were nil; GIG's redemption from the SB MIN (EUR) Compartment amounted to approximately half of the value of its initial investment; and MDM's redemption from the SB MIN (USD) Compartment amounted to USD c.850,000 of his initial investment of USD 1.5m.

- The effect was that all of the capital invested by GIG in the SB HFPO Compartment was lost; GIG lost approximately half of the capital it had invested in the SB MIN Compartment; and MDM lost approximately 43% of the capital he had invested in the SB MIN (USD) Compartment.

- GIG's investments in the Real Estate Compartment of the Skew Base Fund were successful. The redemption of GIG's shares was processed on 9 December 2021, and payment of funds was made to GIG in the amount of €12,287,102.21. GIG therefore made returns of approximately 23%.

- GIG's and MDM's investments in the Tangible Credit Compartment of the Skew Base Fund did not suffer a loss. GIG's shares were redeemed between July 2020 and December 2020 for a total amount of €14,434,221.47, being a return of approximately 3.1%. MDM's shares were redeemed between July 2020 and December 2020 for a total amount of €3,116,313.27, being a return of approximately 3.9%.

A5: Scheme of this judgment

- This judgment contains the following sections.

- Section B sets out my overall approach to evaluating the extensive factual evidence in this case, including significant disputes of fact concerning, in particular: (i) whether the Claimants were aware of any connections between Mr Migani/XY and the Skew Base Fund; (ii) whether and to what extent the Claimants were informed of and understood the risks of the investments which they made; (iii) whether there was a conspiracy to conceal matters from the Claimants and other investors. It also contains a summary of my assessment of the evidence of each of the witnesses, and this draws upon conclusions which I reach later in the judgment.

- Section C describes the "structured products" with which this case is concerned: i.e. the MIN and HFPO products in which the Claimants invested outside the Skew Base Fund, and also by investing in the Fund itself.

- Section D contains a chronological account of the dealings between the Claimants and XY from 2016 to the breakdown of the relationship in 2020. These dealings are relevant to key issues in the case concerning the misrepresentation and conspiracy claim, including the issues concerning (i) what representations were made; (ii) the Claimants' alleged knowledge of connections between XY/Mr Migani and the Skew Base Fund; and (iii) the Claimants' understanding of the risk of the investments which they made.

- Section E describes the terms of the Offering Memoranda for the investments made in the Skew Base Fund.

- Section F describes the origin, formation (including the contractual documents) and operation of the Skew Base Fund. This overlaps in time with the matters covered in Section D, but I do not consider it sensible to seek to interweave these matters into the chronology of the dealings between the Claimants and XY.

- Section G addresses the case of fraudulent and negligent misrepresentation concerning the "investment representations" relied upon by the Claimants.

- Section H addresses the case of fraudulent misrepresentation concerning the "independence representations" relied upon by the Claimants.

- Section I addresses the claim against XY for breach of fiduciary duty, and against Mr Migani for dishonest assistance.

- Section J addresses the claim in conspiracy, albeit that my conclusions in that regard are largely foreshadowed by the factual findings and conclusions in Sections F and H.

- Section K addresses the remaining 'non-fraud' claims i.e. the contractual, tortious and regulatory claims which are advanced against XY.

- Section L addresses XY's counterclaim.

Section B: Approach to the evidence and witnesses

B1: Approach to the evidence

- The trial occupied 28 days, including 20 days of evidence from a large number of factual witnesses. The evidence covered (in particular) the history of the dealings between the Claimants and XY and the formation and operation of the Skew Base Fund, including the roles and work carried out by the various Defendants in relation to the Fund. There was no expert evidence, as a result of a decision made at a case management conference that expert evidence was not necessary. During the early part of the trial, in particular when MDM and other Claimants' witnesses were giving evidence, the court's air conditioning system was not working properly. I have taken into account the difficulties and discomfort which the high temperatures in the court presented for the witnesses.

- The case involves acute conflicts of evidence between the Claimants' witnesses (in particular Mr Nuzzo and MDM) and XY's witnesses as to what they were told during the course of the meetings and discussions that they had. The conspiracy case draws to some extent on the evidence of the Claimants' witnesses as to what they were told. It is, however, largely advanced on the basis that the court can conclude on the documents and the inherent probabilities, despite the denials of the various witnesses called by the Defendants, that there was indeed a conspiracy and that the legal requirements of that cause of action are fulfilled. Accordingly, the credibility and reliability of the witnesses is a critical part of the present case, in particular in relation to the two issues which Mr Cloherty identified as central, namely: (i) did the Claimants understand the risks involved in the investments which they made; and (ii) did they know of a significant connection between Mr Migani/XY and the Skew Base Fund?

- In assessing the evidence of the factual witnesses on all issues, I will apply the approach commended by Robert Goff LJ in Armagas Ltd v Mundogas SA (The Ocean Frost), [1985] 1 Lloyd's Rep 1, 57:

"Speaking from my own experience, I have found it essential in cases of fraud, when considering the credibility of witnesses, always to test their veracity by reference to the objective facts proved independently of their testimony, in particular by reference to the documents in the case, and also to pay particular regard to their motives and to the overall probabilities. It is frequently very difficult to tell whether a witness is telling the truth or not; and where there is a conflict of evidence such as there was in the present case, reference to the objective facts and documents, to the witnesses' motives, and to the overall probabilities, can be of very great assistance to a Judge in ascertaining the truth."

- In that same case, Dunn LJ said (to similar effect):

"I respectfully agree with Lord Justice Browne when he said in re F, [1976] Fam. 238 at p. 259, that in his experience it was difficult to decide from seeing and hearing witnesses whether or not they are speaking the truth at the moment. That has been my own experience as a Judge of first instance. And especially if both principal witnesses show themselves to be unreliable, it is safer for a Judge, before forming a view as to the truth of a particular fact, to look carefully at the probabilities as they emerge from the surrounding circumstances, and to consider the personal motives and interests of the witnesses. As Lord Wright said in Powell v. Streatham Manor Nursing Home sup. at p. 267:

. . . Yet even where the Judge decides on conflicting evidence, it must not be forgotten that there may be cases in which his findings may be falsified, as for instance by some objective fact . . .

and he referred in particular to some conclusive document or documents which constitute positive evidence refuting the oral evidence of the witnesses."

- The approach of Robert Goff LJ was approved by the Privy Council in Grace Shipping v Sharp & Co [1987] 1 Lloyd's Rep 207, 215-216:

"And it is not to be forgotten that, in the present case, the Judge was faced with the task of assessing the evidence of witnesses about telephone conversations which had taken place over five years before. In such a case, memories may very well be unreliable; and it is of crucial importance for the Judge to have regard to the contemporary documents and to the overall probabilities.

…

That observation [i.e. of Robert Goff LJ] is, in their Lordships' opinion, equally apposite in a case where the evidence of the witnesses is likely to be unreliable; and it is to be remembered that in commercial cases, such as the present, there is usually a substantial body of contemporary documentary evidence."

- Robert Goff LJ's judgment was described as the "classic statement" in Simetra Global Assets Ltd v Ikon Finance Ltd [2019] EWCA Civ 1413, where Males LJ said at para [48]:

"In this regard I would say something about the importance of contemporary documents as a means of getting at the truth, not only of what was going on, but also as to the motivation and state of mind of those concerned. That applies to documents passing between the parties, but with even greater force to a party's internal documents including emails and instant messaging. Those tend to be the documents where a witness's guard is down and their true thoughts are plain to see. Indeed, it has become a commonplace of judgments in commercial cases where there is often extensive disclosure to emphasise the importance of the contemporary documents. Although this cannot be regarded as a rule of law, those documents are generally regarded as far more reliable than the oral evidence of witnesses, still less their demeanour while giving evidence."

- Robert Goff LJ's approach is also reflected in authorities such as Gestmin SGPS SA v Credit Suisse (UK) Ltd at [2013] EWHC 3560 (Comm) at paras [15] – [23] ("Gestmin"). The unreliability of human memory was discussed in that case and in subsequent authorities, including Jaffe v Greybull Capital LLP [2024] EWHC 2534 (Comm) (Cockerill J) at paras [195] – [202]. That decision itself refers to Popplewell LJ's Combar lecture "Judging Truth from Memory". Even more recently, in Mohammed v Daji [2024] EWCA Civ 1247 Newey LJ (giving the lead judgment in the Court of Appeal) said at para [45]:

"Judges have for many years remarked on the vulnerabilities of evidence as to what witnesses remember. Popplewell LJ recently discussed human memory and how witnesses can come to give mistaken evidence in his 2023 COMBAR lecture, Judging Truth from Memory: The Science. In Gestmin SGPS SA v Credit Suisse (UK) Ltd [2013] EWHC 3560 (Comm), [2020] 1 CLC, at paragraph 22, Leggatt J went so far as to suggest that "the best approach for a judge to adopt in the trial of a commercial case is … to place little if any reliance at all on witnesses' recollections of what was said in meetings and conversations, and to base factual findings on inferences drawn from the documentary evidence and known or probable facts". However, Popplewell LJ explained in his lecture that he did not himself wholly agree with this remark and in Natwest Markets plc v Bilta (UK) Ltd [2021] EWCA Civ 680 the Court of Appeal pointed out at paragraph 50 that "it is important to bear in mind that there may be situations in which the approach advocated in Gestmin will not be open to a judge, or, even if it is, will be of limited assistance". In Kogan v Martin [2019] EWCA Civ 1645, [2020] FSR 3, the Court of Appeal said at paragraph 88 that "a proper awareness of the fallibility of memory does not relieve judges of the task of making findings of fact based upon all of the evidence"."

- Thus, although the decisions recognise the fallibility of human memory, it does not follow that the testimony of witnesses is somehow to be sidelined. In Kogan v Martin [2019] EWCA Civ 1645, the Court of Appeal said (at para [88]) that the judge in that case had been wrong to view Gestmin as an admonition against placing any reliance at all on the recollections of witnesses:

"We consider that to have been a serious error in the present case for a number of reasons. First, as has very recently been noted by HHJ Gore QC in CBX v North West Anglia NHS Trust [2019] 7 WLUK 57, Gestmin is not to be taken as laying down any general principle for the assessment of evidence. It is one of a line of distinguished judicial observations that emphasise the fallibility of human memory and the need to assess witness evidence in its proper place alongside contemporaneous documentary evidence and evidence upon which undoubted or probable reliance can be placed. Earlier statements of this kind are discussed by Lord Bingham in his well-known essay The Judge as Juror: The Judicial Determination of Factual Issues (from The Business of Judging, Oxford 2000). But a proper awareness of the fallibility of memory does not relieve judges of the task of making findings of fact based upon all of the evidence. Heuristics or mental short cuts are no substitute for this essential judicial function. In particular, where a party's sworn evidence is disbelieved, the court must say why that is; it cannot simply ignore the evidence."

- My approach is therefore to consider the objective evidence and in particular the documentary evidence, as well as the inherent probabilities, and to test the accounts of the witnesses against those matters. Even though this is a commercial case with a substantial number of documents, the oral evidence of witnesses remains important, not least because: (i) there were a very large number of meetings between the Claimants and XY over a number of years, and these clearly involved substantial discussions between the parties; and (ii) the Claimants' conspiracy case is substantially based upon inferences to be drawn from certain events and documents, and oral evidence from witnesses may put those events and documents into context.

- I was also referred to the very helpful summary by Calver J of the principles applicable to cases of fraud and conspiracy, in particular the drawing of inferences, in Suppipat v Narongdej [2023] EWHC 1988 (Comm) at para [904]:

"I also bear in mind that as to inferring fraud or dishonest conduct generally:

a. It is not open to the Court to infer dishonesty from facts which are consistent with honesty or negligence, there must be some fact which tilts the balance and justifies an inference of dishonesty, and this fact must be both pleaded and proved: Three Rivers District Council v Bank of England [2001] UKHL 16; [2003] 2 AC 1, [55]-[56] per Lord Hope and [184]-[186] per Lord Millett.

b. The requirement for a claimant in proving fraud is that the primary facts proved give rise to an inference of dishonesty or fraud which is more probable than one of innocence or negligence: JSC Bank of Moscow v Kekhman [2015] EWHC 3073 (Comm) at [20] per Bryan J; Surkis & Ors v Poroshenko & Anr [2021] EWHC 2512 (Comm) at [169 (iv)] per Calver J.

c. Although not strictly a requirement for such a claim, motive " is a vital ingredient of any rational assessment " of dishonesty: Bank of Toyo-Mitsubishi UFJ Ltd v Baskan Sanayi Ve Pazarlama AS [2009] EWHC 1276 (Ch) at [858] per Briggs J. By and large dishonest people are dishonest for a reason; while establishing a motive for conspiracy is not a legal requirement, the less likely the motive, the less likely the intention to conspire unlawfully: Group Seven Ltd v Nasir [2017] EWHC 2466 (Ch) at [440] per Morgan J.

d. Assessing a party's motive to participate in a fraud also requires taking into account the disincentives to participation in the fraud; this includes the disinclination to behave immorally or dishonestly, but also the damage to reputation (both for the individual and, where applicable, the business) and the potential risk to the " liberty of the individuals involved " in case they are found out: Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ Ltd v Baskan Sanayi Ve Pazarlama AS [2009] EWHC 1276 (Ch) at [858], [865] per Briggs J."

- In approaching the evidence in this case, I of course bear in mind that the events with which the trial are concerned took place many years ago. It was obvious that there are many matters which mean that the evidence as to what precisely was said at a particular meeting or discussion is unlikely to be wholly reliable, including because of the passage of time and the fact that there were a very large number of meetings and discussions between the Claimants and XY. It is also obvious that the principal witnesses on both sides have much to gain or lose from the present litigation, which has been bitterly fought for many years, and that this will inevitably colour the ability of some of the witnesses to give objective evidence about the relevant events.

- In the context of serious allegations, such as the deceit and conspiracy allegations in this case, I also approach the case bearing in mind the following passage from Fiona Trust & Holding Corp v Privalov [2010] EWHC 3199 (Comm) (which has been recently cited, with approval, by Sir Geoffrey Vos C in Bank St Petersburg PJSC v Arkhangelsky [2020] EWCA Civ 408 at paras [46] – [47] ("Arkhangelsky")):

"[it] is well established that 'cogent evidence is required to justify a finding of fraud or other discreditable conduct': per Moore-Bick LJ in Jafari-Fini v Skillglass Ltd [2007] EWCA Civ 261 at [73]. This principle reflects the court's conventional perception that it is generally not likely that people will engage in such conduct: 'where a claimant seeks to prove a case of dishonesty, its inherent improbability means that, even on the civil burden of proof, the evidence needed to prove it must be all the stronger', per Rix LJ in Markel International Insurance Company Ltd v Higgins [2009] EWCA Civ 790 at [50]. The question remains one of the balance of probability, although typically, as Ungoed-Thomas J put it in In re Dellow's Will Trusts [1964] 1 WLR 451, 455 (cited by Lord Nicholls in In re H [1996] AC 563, 586H), 'The more serious the allegation the more cogent the evidence required to overcome the unlikelihood of what is alleged and thus to prove it'. Associated with the seriousness of the allegation is the seriousness of the consequences, or potential consequences, of the proof of the allegation because of the improbability that a person will risk such consequences: see R (N) v Mental Health Review Tribunal (Northern Region) [2005] EWCA Civ 1605; [2006] QB 468, para 62, cited in In re D (Secretary of State for Northern Ireland intervening), [2008] UKHL 33; [2008] 1 WLR 1499, para 27, per Lord Carswell."

- In Arkhangelsky, Males LJ said at para [117]:

"In general it is legitimate and conventional, and a fair starting point, that fraud and dishonesty are inherently improbable, such that cogent evidence is required for their proof. But that is because, other things being equal, people do not usually act dishonestly, and it can be no more than a starting point. Ultimately, the only question is whether it has been proved that the occurrence of the fact in issue, in this case dishonesty in the realisation of the assets, was more probable than not."

- I agree with the Claimants that this does not mean that the more serious the allegation, the more convincing the evidence required. Ultimately, I must decide this case on the balance of probabilities.

- In assessing the evidence of the various witnesses, I have endeavoured to take into account their evidence as a whole. It does not follow from the fact that the evidence of a witness on a particular issue is to be rejected, or that a witness gave a single bad answer or series of bad answers, that everything that a particular witness has said is to be rejected. The evidence of a witness as to one part of the case may be consistent with the documents or inherent probabilities, whereas his or her evidence on another area of the case may be otherwise. Accordingly, where the factual evidence of a particular witnesses on a particular topic is important, I address that evidence in more detail below in the context of that topic. However, I start by giving some general observations which are reflected in my fact-findings later in this judgment. What follows should therefore be read together with those later fact-findings.

The Claimants' witnesses

- On the Claimants' side, the witnesses were Mr Marco Nuzzo, MDM, Mr Matteo Facoetti and LDM.

- Mr Nuzzo: As described in Section A above, Mr Nuzzo is the longstanding trusted advisor to, and agent of, LDM and the di Montezemolo family in relation to their investment assets. Before working with the di Montezomolo family, he had worked as an international tax consultant for two trust companies, and also completed a master's degree in international tax. He started working for the family in 2011, having grown up with MDM and known both him and LDM for a long time. In his witness statement, he described how he slowly started to become more sophisticated on the investment side when working with the family. His work for the family meant working for LDM personally, and also being involved in administering his family wealth. Mr Nuzzo is currently a director, manager or officer of about 19 companies associated with the family. When the family office relocated to London in 2016, his salary was £ 400,000 per annum. His remuneration also potentially includes a discretionary bonus, which in 2019 was £ 1,200,000. That particular bonus reflected the successful sale of an equity investment which generated the "new liquidity" which was then discussed with XY in 2018.

- It is apparent to me that, over the years, Mr Nuzzo (who is a highly intelligent person generally and in relation to financial matters, as indeed were all of the Claimants' witnesses) acquired considerable familiarity with different types of investments, including those which are at the heart of the case. This is borne out by a spreadsheet, produced by XY based on their running a portal as part of the technology services which were provided to the Claimants. This shows a very large number and variety of different types of investment, made over the years, by Mr Nuzzo when acting for GIG and LDM.

- When giving evidence, Mr Nuzzo was in my view a much better witness than MDM (described below) and was willing to make appropriate concessions. This is illustrated by his evidence, described in Section H below, which frankly accepted the importance of a general partner in the context of a fund such as the Skew Base Fund. However, his witness statement contained in my view a degree of exaggeration in relation to what he was told and understood about the risks of investing in MIN and HFPO products. His oral evidence also underplayed, in my view, the extent of his knowledge and understanding of the risks of the investments which he was making. I illustrate this in Section D.

- Overall, I thought that he was generally an honest witness, who was seeking to answer questions to the best of his ability, but one whose recollection and evidence had been coloured by the very substantial losses suffered on his watch. For example, he has in my view persuaded himself that in September 2018, he received reassurance about the risks being "standard". I have not accepted that that conversation took place. There are other aspects of his evidence that I have not accepted, as described in Section D: for example, that he did not receive answers from Mr Dalle Vedove to pertinent questions that he had asked. I was also not persuaded by his evidence on some of the more difficult (from the Claimants' perspective) documents which suggested that Mr Nuzzo knew of the connections between Mr Migani/XY and the Skew Base Fund.

- MDM: MDM's background in finance and investment is described in Section A above. I had significant reservations about MDM's evidence, and I treat his evidence on key issues with considerable caution. I discuss aspects of his evidence in some detail in the context of the investment representations claim. It seemed to me that, as a generality, MDM consistently sought to downplay (to an extent greater than Mr Nuzzo) his understanding of what he was being told about the nature of the investments in the strategy which was being suggested to him. I accept that he was not a specialist in structured products, but that does not mean that he would not have applied his financial intelligence and experience to understanding what he was told, asking questions if he did not understand an important matter. MDM was clearly financially astute and experienced, and I cannot accept that he would have been investing very substantial sums of money in the Skew Base Fund, or investments outside the Fund, with no real understanding of what the investments entailed or what the risks were. Similarly, I was not impressed with his answers, at the start of his cross-examination, to the effect that he had little understanding of AIFs, when in fact he ran (and was the CEO of the general partner of) a number of such funds.

- It is also the case that MDM pursued to trial a claim against Mr Faleschini on the basis of an allegation that he had relied upon representations he had made. That case collapsed in cross-examination, and was thereafter abandoned. I have been given no explanation as to how it was that MDM (and also his father) came to make this allegation of fraud against Mr Faleschini, in circumstances where MDM had not relied on anything that he had said, and indeed LDM did not even know who he was. This is in my view a point which does reflect adversely on MDM's credibility. It also suggests that there is an element of what Mr Cloherty and others called "reverse engineering" of the claim: i.e. advancing a case on the basis of the result to be achieved, rather than on the basis of the actual facts.

- Mr Facoetti: Mr Facoetti was a more peripheral witness. He has been working for MDM since 2007, when he joined his private equity firm. He is a partner and CFO at the firm, and he also helps MDM with some of his personal affairs. His evidence was that it was MDM who made the decisions. He was not present at many of the meetings which featured in the evidence and did not participate in the 2 December 2016 call when MDM was introduced to the possibility of investing in a Luxembourg fund. Nor was he present at the 2018 meeting when Mr Nuzzo was introduced to the Skew Base Fund.

- There were occasions in his evidence when Mr Facoetti showed himself as a witness whose recollections were coloured by a desire to assist MDM in his case. This was evident when (see Section D) he sought to explain away an e-mail where MDM had referred to the possibility of making a speculative investment. It was also evident when Mr Facoetti sought, in re-examination, to retreat from an unhelpful answer that he had given concerning Mr Migani having chosen VP Bank as the custodian. That answer lent some support to the case that the Claimants knew that Mr Migani was the person behind the Skew Base Fund, since it would otherwise be difficult to see why Mr Migani would have been choosing the custodian. That said, I accept that Mr Facoetti was an honest witness, and one who was trying to assist the court to the best of his recollection. His witness statement acknowledged that the investments made by MDM had a risk of losing all the capital, although this was "a very very small risk".

- I did not think that his evidence was of any real assistance on the question of whether MDM knew about the connection of Mr Migani/XY to the Skew Base Fund. Mr Facoetti said that he did not know, and did not care whether there was a commercial relationship between XY and the Fund. In my view, if the connections had been a matter mentioned at one of the meetings that he attended, or by MDM in his discussions with Mr Facoetti, it is unlikely that this would have provoked a reaction on the part of Mr Facoetti.

- LDM: LDM has a very distinguished background, as described in Section A. He was clearly an honest witness, but one who had no real recollection of the meetings about which he gave evidence.

The witnesses called by XY and Twinkle (and related parties)

- Mr Migani: Mr Migani is the CEO and founder of the XY group of companies, and in that role is a director of XY. After graduating in physics in 1997, he worked in nuclear research at the CERN laboratory in Switzerland. He then studied for an MBA and joined Boston Consulting Group. He then left to focus on technology solutions and consulting in the financial services industry, particularly in private wealth. When working for a bank in Switzerland, he saw an opportunity to develop a new service offering for ultra-high net worth individuals, which would use technology-based analysis to look at their global estates. He started a company called Maetrica, which provided various technology-based services. He then decided, in around 2011-2012, to develop a new offering to combine that type of work with consultancy services. The new business became the XY Group. When he founded Maetrica, and in the early years of the XY Group, his time was mainly spent in developing processes and solutions and providing services to clients. By 2016, by which time the XY business had grown, his role was less operational and more focused on supervising service delivery and on new client and business development. He said in evidence that, by the time of the events with which I am concerned, the XY business overall employed around 60 people.

- Mr Migani was cross-examined for some 4 ½ days. Although much of his evidence was sensible and largely consistent with the documents and inherent probabilities, I do not consider him generally to be a reliable witness, and I treat his evidence with very considerable caution. Generally speaking, I do not regard Mr Migani as a witness on whose evidence I can rely, unless corroborated by other reliable evidence in the case including the inherent probabilities.

- I consider that he has sought during this case, unconvincingly, to distance himself from his involvement with Twinkle. A number of documents, admittedly authored by Ms Gaveni, describe Mr Migani as the "General Manager" or the "Managing Director" of Twinkle. In particular, the description of Mr Migani as "General Manager" was included in a set of slides which were used during a due diligence visit by VP to Twinkle's offices in Mendrisio in March 2019, and which were then sent to VP afterwards. A due diligence exercise is a serious matter, and this particular due diligence was carried out by a team of 3 people, two of whom were very senior: Mr Ries, Mr Stein (who was the Chief Risk Officer at VP Lux) and Mr Kone. In my view, there would be no justification for Ms Gaveni (who by that time had worked for Twinkle for many months) to have given incorrect information to VP as to Mr Migani's role. I was not impressed by Mr Migani's evidence (supported by Mr Faleschini and Ms Gaveni) that this was not an accurate statement of the position.

- It may well be the case that Mr Migani's day-to-day work for Twinkle was relatively limited. His employment contract with Twinkle, apparently terminated in April 2021 with effect from 30 June 2021, referred to him working only 4 hours a week. However, there is nothing in the contract which suggests that Mr Migani's work was to be limited to real estate business or consultancy. It is far more probable, as suggested by the documents referred to in the previous paragraph, that Mr Migani had a more general role. That would be unsurprising, in circumstances where he was the ultimate beneficial owner of Twinkle, and where the two directors of Twinkle (Mr Grasso and later Mr Faleschini) had no real investment expertise. The structure charts showed the operational team, headed by Mr Negro, reporting to Mr Migani as the General Manager, and it seemed to me that this would be the natural reporting line.

- I am also very troubled by the fact that, at a time after the Swiss criminal proceedings had begun, steps were taken to delete (irretrievably) Mr Migani's Twinkle e-mail account. The purported justification for the deletion did not stand up to scrutiny. At the time when Twinkle was separately represented in these proceedings, their solicitors had advised that Mr Migani's Twinkle e-mail account was deleted at some time between February and April 2021. There is no record of when exactly it was deleted. However, deletion at that time, on the basis of the undesirability of keeping an e-mail account after an employee has left a company, makes no sense. Mr Migani's employment was only terminated in April 2021, with effect from June 2021. In any event, since Swiss criminal proceedings had been commenced, it is obvious that the account should have been preserved. Mr Faleschini said that the deletion occurred after he had spoken with the IT manager (of both Twinkle and XY) and Mr Migani. Accordingly, both Mr Migani and Mr Faleschini were party to this deletion.

- It is also my view that Mr Migani did not give a frank account of the operation of the Skew Base Fund during the phone call with an investor, Finfloor, in (as I was told) around April 2020. A transcript of that call was obtained, apparently covertly. However, it was the subject of cross-examination and Mr Cloherty did not ultimately press a point that it was inadmissible. No one from Finfloor has been called to give evidence as to what they did or did not know, and I cannot make any findings about that. I can say that I do find it surprising that "Giovanni", the main speaker for Finfloor, should have said that he was not aware that there was an important leverage within the funds – when the Offering Memorandum makes the ability to borrow money very clear. So it may be, as Mr Migani suggested in his evidence, that Finfloor knew rather more on a number of issues than might appear to be the case from the transcript.

- However, what is clear is that Mr Migani was asked on two occasions to explain his relationship with the Skew Base funds. When he was first asked, he was keen only to answer from the perspective of "XY as a group". Mr Migani said in evidence that this was on legal advice, in circumstances where a claim from Finfloor was anticipated imminently and where the client relationship was between XY and Finfloor. I have no way of assessing whether this was the legal advice. I accept, as Mr Migani said, that this was a very difficult call at a very fraught time, with litigation on the horizon. But I am not persuaded that this means that Mr Migani should not have given frank answers to the questions asked. A frank answer to the question would have involved not simply answering by reference to XY, but rather referring (at least) to the relationship which Twinkle had with the Skew Base Fund. Later in the call, Giovanni asked again, saying he wanted to understand "what your direct relationship was with the VP funds", and a little later "I wanted to understand what your relationship was with the funds and with the VP Bank". Again, Mr Migani answered by reference to XY's position, and omitted any reference to Twinkle or indeed his ownership of the general partner. The focus of the call was the recent collapse of the HFPO and MIN Compartments, and it seems to me that Mr Migani was – by omitting any mention of Twinkle – seeking to distance himself and XY from responsibility for the collapse.

- I also found Mr Migani's answers, about some important documents, to be surprising and unconvincing. For example, when asked about Mr Dalle Vedove's e-mail of 14 December 2016 (see Section D below), he was unwilling to accept that there was any reference to investment objectives. When asked about statements made on XY's website as to independence, being conflict-free and unbiased, he sought to draw a distinction between high level strategic consulting advice, and advice on specific investments. The theme of his evidence was that it was always for the client to decide on the latter. But he was asked whether his position was that "you were going to be giving unbiased and conflict-free strategic advice, but when it came to recommending specific instruments you were entitled to act in a biased way, is that your evidence". His answer was:

"The question is really difficult, but my point is, I did what is written in the contract. There is no mention of independence in the contract. So I did, what was written in the contract, which is we support them in the … strategic design of the strategy, in the implementation we supported them, at the end also in the monitoring of the strategy, okay. So we did exactly what was written in the contract".

I did not consider that the question was really difficult: since I cannot see how the giving of unbiased and conflict-free advice should only apply at the stage where strategic advice was being given.

- Mr Dalle Vedove: Mr Dalle Vedove was given the role as "minder" to the Claimants. He was, in effect, their relationship manager on a day-to-day basis. He attended all the XY meetings with the Claimants, except for the initial meetings in the early summer of 2016. Mr Dalle Vedove had a Master of Science degree and a PhD in management engineering. His PhD was focused on corporate finance. He then joined the management consulting firm McKinsey & Co in Milan in October 2007, and worked there for 6 years. He started working for Mr Migani's company, Maetrica, in May 2013, and then moved to XY in June 2014. He became an employee of another company, XY Ticino, in December 2016, and remains an employee of that company today. Mr Dalle Vedove had no role in Twinkle, and there was no suggestion that he was involved with or had access to the info@skewbase e-mail address.

- I thought that Mr Dalle Vedove was an honest witness, and was for the most part impressive. He answered the questions thoughtfully and directly, and generally gave answers which seemed to me to be in line with the documents and probabilities. It also seemed to me that Mr Dalle Vedove's work during the period of his dealings with the Claimants (i.e. from around July 2016 to mid-2020) was of a high professional standard. For example, he was sometimes asked by Mr Nuzzo about investment proposals or ideas from other financial institutions with whom Mr Nuzzo was dealing. Mr Dalle Vedove's answers at the time were generally well-reasoned and well-explained, as were his answers in cross-examination when it was suggested that he was discouraging Mr Nuzzo from investing other than on the basis of XY's proposals. The PowerPoint slide presentations, upon which Mr Dalle Vedove worked, were detailed and well-prepared, and clearly impressed MDM and Mr Nuzzo.

- The Claimants' closing argument described Mr Dalle Vedove (and Mr Negro) as "company men", loyal to Mr Migani for whom they had both worked for a long time. It was submitted that they were corporate foot soldiers prepared to stick to the script to protect themselves and their employer. However, it did not seem to me that the closing submissions contained a great deal of criticism of Mr Dalle Vedove as a witness, and I therefore asked Mr Saoul – during his oral closing – to identify the important points which, on the Claimants' case, showed that Mr Dalle Vedove's evidence was unreliable.

- On Day 24, he identified a number of points, but I did not think that any of them was particularly powerful. For example, he submitted that Mr Dalle Vedove had invented an account of the discussions of the April 2018 questions from Mr Nuzzo concerning fees (described in Section D below). I did not think that Mr Dalle Vedove was inventing an answer, but rather was giving evidence as to what he thought was the likely discussion which had taken place, based on the contemporaneous documents. Another example was Mr Dalle Vedove's response to a question raised by MDM in March 2018, concerning a message received from Mr Kone concerning the merger of the Centaurus Compartment with the HFPO Compartment. Mr Dalle Vedove gave a prompt and clear explanation in response to the question asked, and I did not consider that the question or issue required any reference to Twinkle or that it was in any way misleading.

- In his oral reply, however, Mr Saoul did refer me to Mr Dalle Vedove's evidence in relation to the May 2018 letter requested by Mr Nuzzo. As discussed in Section D, this is one area where I thought that Mr Dalle Vedove's evidence was not accurate and did appear to be given with a view to supporting the evidence given earlier on by Mr Migani.

- Overall, I have fewer reservations about Mr Dalle Vedove's evidence than about the other main witnesses hitherto discussed, Mr Nuzzo, MDM and Mr Migani. I certainly do not think that Mr Dalle Vedove came to court in order to lie about what investors were told. However, I think that it would be naïve not to recognise that Mr Dalle Vedove, as a long-standing employee of XY and someone who has worked closely with Mr Migani for many years, would be motivated to support the XY case. I therefore bear that in mind in my assessment of his evidence. On the key issue concerning the independence representations, and what the Claimants were or were not told about any connection between Mr Migani and the Skew Base Fund, I accept his evidence as to what investors (including the Claimants) were told; because the evidence overall, including the inherent probabilities, support the account which he gave: see Section H below.