1 Introduction

The total population of the globe stands at 7.91 billion, 4.95 billion of whom are Internet users and 4.62 billion active social media users. Internet users grew by 4% between 2021 and 2022 while social media users grew by more than 10% during the same time period.[1] The Internet ‘magnifies the voice and multiplies the information within reach of everyone who has access to it’.[2] For example, in the 2009 case of Times Newspaper Ltd v UK, the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) held that ‘the Internet plays an important role in enhancing the public’s access to news and facilitating the dissemination of information generally’.[3] The United Nations Human Rights Committee (HRC) noted that the Internet and mobile based systems have allowed for the creation of a ‘global network for exchanging ideas and opinions that does not necessarily rely on the traditional mass media intermediaries’.[4] The statements by the ECtHR and the HRC reflect the great leaps forward brought by the Internet to expression, information and communication. However, the increased centralization of content on privately owned social media companies has amplified the harms of free speech and granted phenomena, such as hate speech, new visibility.[5] This reality has led to the horizontalization of hate speech regulation, with several States, such as Germany, enhancing the role of social media platforms (SMPs) to remove certain types of speech at the risk of fines. This paper argues that horizontalizing/privatizing the regulation of the fundamental freedom of expression in today’s central agora, namely SMPs, is not without peril. Specifically, imposing obligations on privately own companies to remove hate speech quickly at the risk of steep fines, places the rights to freedom of expression in a dangerous position. Private companies are not bound by international human rights law (IHRL) and açre inevitably keen to take a ‘better safe than sorry’ approach to regulation, particularly when fines are involved, in order to keep their business models and pockets intact. Whilst the author is cognizant of the UN Guiding Principles of Human Rights,[6] and its contribution to the area of business and human rights, these principles remain voluntary. In brief, IHRL aims to bind States despite steps taken in more recent years to widen this framework. To elucidate on the issues at stake, the paper will commence with a brief definitional framework of hate speech, followed by an overview of its prevalence and removal from SMPs. It will continue with an analysis of central developments in law and policy that are centred around private regulation in the European sphere (both the Council of Europe and the European Union) and in national contexts such as Germany.

2 The Concept of Hate Speech

It is beyond the scope of this paper to dive into the semantics and notions of hate speech.[7] Instead, this section provides a brief overview of the key provisions in international and European law that relate to hate speech. On a United Nations (UN) level, we have two key articles. Article 4 of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (ICERD) prohibits all dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority or hatred and incitement to racial discrimination. Article 20(2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) prohibits any advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence. So, just within a UN framework, we have a significant discrepancy, with the former encapsulating a lower threshold than the latter since it prohibits, for example, dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority (with no necessity for these ideas constitute or call for hatred or violence). On the other hand, the ICCPR prohibits advocacy which actually leads to incitement to certain types of harm. It is not, therefore, sufficient for the ICCPR for speech merely to disseminate ideas of racial or religious superiority. In fact, the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression held that ‘the threshold of the types of expression that would fall under the provisions of Article 20 (2) should be high and solid’.[8] Both Article 4 and Article 20(2) have a series of reservations imposed by several countries on the grounds of freedom of expression concerns. Illustrative of this, for example, is France’s reservation of Article 4 ICERD and Luxembourg’s reservation of Article 20 ICCPR respectively:

In relation to Article 4 (ICERD):

With regard to article 4, France wishes to make it clear that it interprets the reference made therein to the principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and to the rights set forth in article 5 of the Convention as releasing the States Parties from the obligation to enact anti-discrimination legislation which is incompatible with the freedoms of opinion and expression and of peaceful assembly and association guaranteed by those texts.[9]

In relation to Article 20 of the ICCPR:

The Government of Luxembourg declares that it does not consider itself obligated to adopt legislation in the field covered by article 20, paragraph 1, and that article 20 as a whole will be implemented taking into account the rights to freedom of thought, religion, opinion, assembly and association laid down in articles 18, 19 and 20 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and reaffirmed in articles 18, 19, 21 and 22 of the Covenant.[10]

On a European Union (EU) level, Article 1 of the Council Framework Decision 2008/913/JHA of 28 November 2008 on Combatting Certain Forms and Expressions of Racism and Xenophobia holds that:

Each Member State shall take the measure necessary to ensure that publicly inciting to violence or hatred directed against a group of persons or a member of such a group defined by reference to race, colour, religion, descent or national or ethnic origin.

In terms of thresholds, the EU’s Framework Decision endorses a high threshold as conduct needs to be intentional, the expression must be public and incite violence or hatred (not discrimination as in the case of Article 20(2) ICCPR). The threshold is further raised by Article 1.2 which holds that Member States may choose to punish only conduct which may disturb public order or which is threatening, abusive or insulting.

On a Council of Europe level, the Additional Protocol to the Cybercrime Convention criminalizes acts of a racist and xenophobic nature committed through computer systems, including the very low threshold theme of racist insults. Unsurprisingly, Article 5 of the Additional Protocol, which criminalizes racist and xenophobic insults, has come with reservations on the grounds of freedom of expression from countries, such as Finland, which held that:

The Republic of Finland, due to established principles in its national legal system concerning freedom of expression, reserves the right not to apply, in whole or part, Article 5, paragraph 1, to cases where the national provisions on defamation or ethnic agitation are not applicable.[11]

None of the relevant laws available at an international or European level provide any definition of hate speech. However, we do have relevant soft law. One of the few documents, albeit non-binding, which has sought to elucidate the meaning of hate speech, is the Recommendation of the Council of Europe Committee of Ministers on hate speech.[12] It provides that this term is to be ‘understood as covering all forms of expression which spread, incite, promote or justify racial hatred, xenophobia, anti-Semitism or other forms of hatred based on intolerance, including intolerant expression by aggressive nationalism and ethnocentrism, discrimination and hostility against minorities, migrants and people of immigrant origin’. Interestingly, the Recommendation incorporates the justification of hatred as well as its spreading, incitement and promotion, allowing for a broad spectrum of intentions to fall within its definition.

Further, General Policy Recommendation 15 on Combatting Hate Speech adopted by the European Commission against Racism and Intolerance (ECRI), defines hate speech broadly, extending it not only to hatred but also to stereotyping and insult. Specifically, hate speech is defined as:

The advocacy, promotion or incitement, in any form, of the denigration, hatred or vilification of a person or group of persons, as well as any harassment, insult, negative stereotyping, stigmatization or threat in respect of such a person or group of persons and the justification of all the preceding types of expression, on the grounds of “race”, colour, descent, national or ethnic origin, age, disability, language, religion or belief, sex, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation and other personal characteristics or status.

Although the ECtHR has not defined hate speech in its jurisprudence, in its 2020 judgement of Lilliendahl v Iceland, the Court recognized two categories of ‘hate speech.’[13] The first includes the ‘gravest forms of hate speech’ which fall under the non-abuse clause of Article 17 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), which are excluded from Article 10 protection by default. The second is comprised of ‘less grave’ forms of hate speech which do not entirely fall under the protection of Article 10 but for which the Court has ruled that restriction is in fact permissible. This second category extends not only to ideas that call for violence, but also to, amongst others, insults, ridiculing or slandering specific groups and their members.

Turning to platforms themselves,[14] we see Facebook and Instagram conceptualize hate speech in the form of a ‘direct attack’ based on an extensive list of protected characteristics such as race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, caste, and serious disease. Such an attack is broadly defined as ‘violent or dehumanizing speech, harmful stereotypes, statements of inferiority, expressions of contempt, disgust or dismissal, cursing and calls for exclusion or segregation’. [15]A low threshold of permissible speech is also adopted by other platforms, such as: YouTube which extends prohibition to, for example, slurs and stereotypes; TikTok which also refers to slurs; and Twitter which prohibits, amongst others, slurs, epithets, racist and sexist tropes or other content that degrades a person.

In brief, it appears that Article 20(2) of the ICCPR offers the most speech protective approach to the handling of hate speech. The high protection threshold in the EU’s Framework Decision must not be disregarded. Two disclaimers are made here, however, namely that this only extends to speech against one’s race or religion and that it solely involves the use of criminal sanctions (hence the high thresholds). The ECtHR took quite a while (2020) to reach some kind of hate speech conceptualization, which is essentially a categorization of hate speech rather than a definitional framework. Apart from the Additional Protocol to the Cyber Crime Convention, the other laws and policies have not been particularly developed for online hate speech but can be and are transposed to the online setting. With this in mind, the brief overview of some of the platforms’ terms vis-à-vis hate speech demonstrates that a rather low protection of freedom of expression has entered the arena of online content moderation by platforms, steering away from the speech protectiveness set out in Article 20(2) of the ICCPR.

3 Online Landscape: Platform Traffic, Removal Rates and Artificial Intelligence

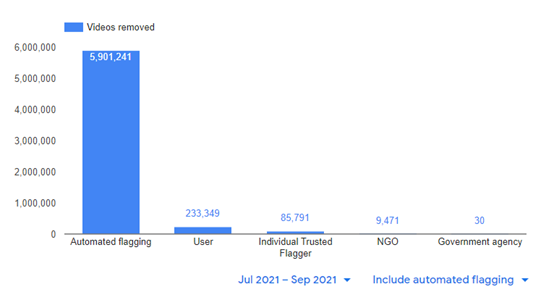

Online hate speech is ‘heterogeneous and dynamic’,[16] fluctuating in time and space and changing as to its targets, according to contextual developments, including, for example, elections, terrorist attacks and, more recently, health crises. Whilst the predominant narrative is that hate speech flows rampantly on SMPs, research has demonstrated that its existence is less prevalent than that. For example, in a study by Siegel et al, which looked at whether Donald Trump’s 2016 election campaign and the six months following it led to a rise in hate speech, 1.2 million tweets were assessed, 750 million of which were election-related and 400 million which were random samples. It was determined that, on any given day, between 0.001% and 0.003% of the examined tweets contained hate speech.[17] In addition to the issue of prevalence is that of regulatory impacts. On the one hand, there are cases of hate speech inciting real life harm, as was the case with the genocide of Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar where Facebook has been accused of negligently facilitating the atrocities committed after its algorithm allegedly amplified hate speech and the platform failed to remove hateful posts.[18] It is indisputable that, within the spirit of IHRL and the Guiding Principles on Businesses and Human Rights, Facebook had a duty to respond efficiently and effectively to hateful posts which were culminating into a tragedy. On the other hand, how to handle content which is not matched with a real-life harm of violence is more contentious. Deciphering which is which is not an easy task, one requiring human moderation, rather than unsupervised Artificial Intelligence (AI), and one which Danish think tank Justitia proposes should be done using principles and tests of IHRL.[19] Whilst the psychological trauma and fear which targets may experience is a reality, ‘it does not necessarily follow that banning hate speech is an efficient remedy that may be implemented without serious risks to freedom of expression’.[20] To add to this, broad conceptualizations of hate speech and stringent obligations on SMPs to remove content quickly may actually lead to the silencing of already marginalized groups. As well as ‘hate speech laws’ passed by authoritarian or semi-authoritarian governments, such as Venezuela and Turkey to silence political opponents, SMPs themselves may contribute to the silencing due to the enhanced use of AI which provides them with tools to manage increasing content and state pressure. In its latest Community Standards Enforcement Report (for the third quarter of 2021), Facebook said that its proactive rate of removal for hate speech was 96.5%. During the reporting period, it removed 22.3 million pieces of hate speech. As noted in a post on the Transparency Centre, ‘our technology proactively detects and removes the vast majority of violating content before anyone reports it’.[21] In its latest enforcement report (Q3 of 2021), YouTube produced the illustration below, demonstrating the percentage of human flagging and automated flagging across the board of removable content (not just hate speech): [22]

Whilst AI is necessary in areas involving, for example, child abuse and the non-consensual promotion of intimate acts amongst adults, the use of AI to regulate more contentious areas of speech, such as hate speech, is complex. Duarte and Llanso argue that AI has ‘limited ability to parse the nuanced meaning of human communication, or to detect the intent or motivation of the speaker’.[23] As such, these technologies ‘still fail to understand context, thereby posing risks to users’ free speech, access to information and equality’. This has had a direct impact on marginalized groups. Facebook’s Community Guidelines state that:

We recognise that people sometimes share content that includes someone else’s hate speech to condemn it or raise awareness. In other cases, speech that might otherwise violate our standards can be used self-referentially or in an empowering way. Our policies are designed to allow room for these types of speech, but we require people to clearly indicate their intent. If the intention is unclear, we may remove content.[24]

However, Oliva et al have found that AI are just not able to pick up on language used, for example, by the LGBTQ community whose ‘mock impoliteness’ and use of terms such as ‘dyke’, ‘fag’ and ‘tranny’ occurs as a form of reclamation of power and a means of preparing members of this community to ‘cope with hostility’.In the same paper, Oliva et al give several reports from LGBTQ activists of content removal, such as the banning of a trans women from Facebook after she displayed a photograph of her new hairstyle and referred to herself as a ‘tranny’.[25] Another example is a research study which revealed that African American English tweets are twice as likely to be considered offensive compared to others, reflecting the infiltration of racial biases in technology. An assessment of AI tools for regulating harmful text found that African American English tweets are twice as likely to be labelled offensive compared to others.[26]

Edwards discusses the ‘immunity doctrine’[27] of the mid-1990s which perceived Internet intermediaries as ‘technically neutral mere conduits’[28] which ‘were agnostic about users’ content’[29] and were technologically incapable of monitoring such content at any reasonable pace. However, in the current Internet era, the role of intermediaries has drastically developed beyond passive and neutral platforms to ones which even ‘collect, analyze and sort user data for their commercial reasons.’[30] Moreover, intermediaries have the technological capability and financial means to monitor, filter, block and remove the illegal online content. Cohen-Almagor has argued that, if intermediaries provide platforms such as social media networks, messaging services, emails, chat rooms, commentary capacity and so on, they ‘share some moral responsibility for regulating it’.[31] As well as the technological transformation in terms of the capabilities of intermediaries is the issue of enhanced visibility of phenomena, such as hate speech, due to the centralization of content on SMPs. The above developments have prompted States, such as Germany, and institutions, such as the EU, increasingly to demand that SMPs take an active role in the regulation of hate speech. This has led to a radical change in the handling of speech, transforming intermediaries into the ‘new governors of online speech’.[32] Regardless of any capacity building and training that IT companies may undergo, they are not courts of law and no reasonable assumption can ever be made that their decisions will meet the criteria which are anyhow difficult to ascertain. Complex issues come into play when determining restrictions to freedom of expression such as legality, proportionality, and necessity. Combine this with State pressure to remove speech quickly at the risk of fines, leaving nothing but an unrealistic possibility of proper assessment of the speech in question. As noted in Justitia’s report on time frames imposed by national laws on SMPs (such as the 24-hour time frame of the German Network Enforcement Act – NetzDG), requirements such as the ones mentioned above ‘make the individual assessment of content difficult to reconcile with legally sanctioned obligations to process complaints in a matter of hours or days’.[33] The private nature of SMPs and the fact that they are not bound by IHRL contribute to this reality.

4 Legal and Policy Developments

4.1 Enhanced Platform Liability: The NetzDG and its aftermath

With the entry into force of the NetzDG in 2017, Germany became the first country in the world to require online platforms with more than 2 million users in their country to remove content such as insult, incitement, and religious defamation within a time period of as little as 24 hours or risk fines of up to 50 million Euro. Since the adoption of the NetzDG, more than 20 States around the world, including authoritarian regimes such as Venezuela, are copying the paradigm.[34] For example, from 2011 to 2021 the number of journalists imprisoned on charges of ’false news’ has exploded from 1 to 47, according to data from the Committee to Protect Journalists.[35] In India, a climate activist, a journalist reporting on a gang rape case and a politician supporting a farmer’s protest have all been charged with sedition, one of this censorship being the new Information Technology Rules, 2021.[36] Another example of censorship includes the case of Yavesew Shimelis, a prominent government critic. In March 2020, he posted on Facebook that, in anticipation of COVID-19’s impact, the government had ordered the preparation of 200,000 burial places. His Facebook profile was suspended and the police detained him. In April, he was charged under Ethiopia’s new ‘Hate Speech and Disinformation Prevention and Suppression Proclamation No.1185/2020’. His trial commenced 15th May 2020.[37] Since his release, Shimelis is no longer as outspoken. [38]

Further, the NetzDG strategy might lead to a situation in which, as noted by current Special Rapporteur on Opinion and Expression, Irene Khan, intermediaries are ‘likely to err on the side of caution and over-remove content for fear of being sanctioned’. [39]In fact, in June 2020, France’s Constitutional Council addressed these very concerns when it declared unconstitutional several provisions of the Avia Law that required the removal of unlawful content within 1 to 24 hours.[40] The court held that the law restricted the exercise of the freedom of expression in a manner that is not necessary, appropriate, and proportionate.[41]

On a European Union level, in January 2022 the European Parliament adopted the final text of the Digital Services Act (DSA) which will be used in negotiations with Member States. The proposed DSA proposes a notice and action mechanism for the removal of illegal content, with intermediaries acting on the receipt of notices ‘without undue delay’, considering the type of content and urgency of removal. ‘Illegal content’ is ‘defined broadly’ and ‘should be understood to refer to information, irrespective of its form, that under the applicable law is either itself illegal, such as illegal hate speech […] and unlawful discriminatory content’. It also establishes enhanced duties for very large online platforms (over 45 million users in the EU) such as audits, mitigation of risk and compliance officers. As with the NetzDG and considering the Brussels Effect,[42] there is great concern about the impact and out spill of this law on authoritarian states around the globe.[43] At the same time, concern within the EU with deteriorating rule of law and censorship issues in countries such as Poland and Hungary render this law particularly problematic for the Union itself.

Until the DSA is passed, essentially the only direct tool to tackle online hate speech through enhanced platform liability is a voluntary Code of Conduct on Countering Illegal Hate Speech Online whose fate, post DSA, remains unknown. In 2016, the European Commission signed a Code of Conduct on countering illegal hate speech online with Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and Microsoft. In 2018, Instagram, Google+, Snapchat, and Dailymotion announced the intention to join the Code of Conduct. At the onset of the Code’s enforcement, the Commissioner for Justice, Consumers and Gender Equality held that she was certain that the Code could be a ‘game changer’[44] in countering online hate speech. For purposes of the Code, illegal hate speech is speech which falls within the EU’s Framework Decision on Racism and Xenophobia mentioned above. This Code of Conduct included a series of provisions to enhance the role of IT companies in regulating online hate speech. The provision of particular relevance to the current discussion is the requirement for IT companies to remove illegal hate speech within 24 hours of its reporting. For purposes of ensuring that the IT companies have done what they have promised, the European Commission has run a series of monitoring exercises during which NGOs and some public bodies from EU Member States report online hate speech and monitor whether and how the IT companies respond to the reports and how quickly they do so. In the latest available results of a monitoring exercise,[45] it was discerned that overall IT companies removed 62.5% of the content of which they were notified, while 37.5% remained online. This result is lower than the average of 71% recorded in 2019 and 2020.

It has been argued that the Code is ‘ambiguous’ and ‘lacks safeguards against misuse of the notice procedure or unwarranted limitations to free speech’.[46] It has also been argued that the nature of the Code of Conduct, as a European Commission initiative that has not been passed through the European Parliament, has been developed outside the democratic framework and gives enhanced powers to IT companies which may take down ‘legal but controversial speech’.[47]

4.2 The European Court of Human Rights and Online Hate Speech

4.2.1 Delfi v Estonia and News Portals

The leading case on the role of Internet intermediaries in the framework of online hate speech is Delfi AS v Estonia, which was delivered by the Grand Chamber in 2015. The applicant company was the owner of Delfi, an online news portal. At the material time, the option to ‘add your comment’ was included at the end of each news article uploaded onto the portal. Users could make public their own comments and read the comments of others. The comments were generated by users and published automatically without any moderation or editing by Delfi. On average, there were daily comments published by 10,000 readers, with the majority of these being made under pseudonyms. Although there was no pre-screening of comments, there was a notice and removal system. If Delfi received a notice that a comment was insulting, mocking, or inciting hatred, the comment was removed. There was an automatic detection and deletion system for obscene words and a victim of a defamatory comment could notify Delfi to remove the comment. In addition to these safeguards, Delfi had a set of rules for commenting which prohibited insults and the incitement of hostility and violence. The approach adopted by Delfi is like those seen in the framework of most Internet intermediaries, such as new portals and social media platforms, including Facebook, where comments are user-generated but not pre-screened whilst the intermediary only discovers the potentially problematic or illegal nature of a comment if another user notifies them of it.

In 2006, Delfi published a news article entitled ‘SLK Destroyed Planned Ice Road’. SLK was Saaremaa Shipping Company, a public limited liability company. L was a member of the supervisory board of SLK and the company’s sole or majority shareholder at the material time. Within a couple of days, this article attracted 185 comments, approximately 20 of which were personal threats and offensive language against L. Comments, included:

bloody shitheads… they bathe in money anyway thanks to that monopoly and State subsidies and have now started to fear that cars may drive to the islands for a couple of days without anything filling their purses. Burn in your own ship, sick Jew!

The ECtHR found that the measures Delfi had implemented to remove comments, which in the Court’s view amounted to ‘hate speech and speech inciting violence’,[48] were insufficient and led to the six weeks’ delay for removal. The ECtHR underlined that, although the ‘automatic word-based filter may have been useful in some instances, the facts of the present case demonstrate that it was insufficient for detecting comments whose content did not constitute protected speech under Article 10 of the Convention’.[49] On the point of time-frames, an interesting finding from Justitia’s report on removal time-frames[50] is relevant as it demonstrated that domestic authorities took an average of 778.47 days from the date of the alleged offending speech until the conclusion of the trial at first instance. Compare that with the 24-hour time limit that is imposed on SMPs to remove hate speech by some countries, and the conclusions are startling.

In finding no violation of Article 10, the Court reiterated that the comments were of an ‘extreme nature’[51] and also took into account that Delfi was a professionally managed new portal which runs on a commercial basis.[52]Although no further explanation of the link between the status of the news portal and its obligation to remove is given, it can be deduced that the Court imposed obligations on Delfi expeditiously to remove hate speech as it was (i) a professional new portal (ii) for profit. The status of Delfi as a large news portal also lay at the foundation of the Court’s separation of censorship from legal obligation to regulate online hate. More particularly, it found that:

a large news portal’s obligation to take effective measures to limit the dissemination of hate speech and speech inciting violence – the issue in the present case – can by no means be equated to “private censorship”. [53]

The Court also noted that the sanction imposed by the national court was ‘moderate’.[54] In reaching the above position, the Court acknowledged the significance of the Internet which facilitates the dissemination of information but also underlined that it is ‘mindful of the risk of harm posed by content and communications on the Internet’.[55]

In sum, the ECtHR found that Delfi, a large professional and for-profit news portal, had a legal obligation quickly to remove user-generated comments which amounted to hate speech and that the delay of six weeks to do so was not justifiable. This decision has been called ‘unexpected’,[56] ‘controversial’,[57] and a restriction of the freedom of expression.[58] European Digital Rights, an association of civil and human rights organizations from across Europe, which defends rights and freedoms in the digital environment, argued that this decision limits the rights of Internet users as it is ‘not obvious why the Court appears to have given almost absolute priority to third party rights ahead of the free speech rights of commentators’.[59]

4.2.2 SMPs and the Obligation of Individual Users (and the State): Sanchez v France and Beizaras and Levickas v Lithuania:

The ECtHR has also dealt with the issue of posts and comments on SMPs and the responsibility of individuals and the State in relation to such comments.

4.2.2.1 Sanchez v France (2021)

This case[60] involved the criminal conviction of the applicant (at the time, parliamentary candidate for Front National) for inciting hatred or violence against a group of people/an individual on religious grounds. The conviction resulted from his failure to take prompt action in deleting comments that others wrote under one of his posts on Facebook. Sanchez posted a comment about the website of one of his political opponents F.P (a Member of the European Parliament). Under this post, a user, S.B, wrote that F.P. has:

transformed Nîmes into Algiers, there is not a street without a kebab shop and mosque; drug dealers and prostitutes reign supreme, no surprise he chose Brussels, capital of the new world order of sharia […] Thanks [F.] and kisses to Leila ([L.T]) […] Finally, a blog that changes our life […]

Another user, L.R., added three other comments directed at Muslims, such as allegations that Muslims sell their drugs without police intervention and that they throw rocks at cars belonging to ‘whites’. On 26 October 2011, L.T. wrote to the Nîmes public prosecutor to lodge a criminal complaint against Mr. Sanchez and the users who posted the offending comments. A day later, Sanchez posted a message on the wall of his Facebook account inviting users to ‘monitor the content of [their] comments’ but did not remove already posted comments. Sanchez appealed but the Court of Appeal upheld the first instance verdict (but lowered the fine by 1,000 EUR).

In this case, ‘we are dealing with a kind of Féret /Le Pen – Delfi mélange’.[61] The court found that the posts ‘clearly encouraged incitement to hatred and violence against a person because of their belonging to a religion’. In this ambit, it reminded us of its previous positions[62] on what constitutes incitement to hatred and that this:

did not necessarily require the calling of a specific act of violence or another criminal act. Attacks on persons committed through insults, ridicule or defamation aimed at specific population groups or incitation to discrimination, as in this case, sufficed for the authorities to give priority to fighting hate speech when confronted by the irresponsible use of freedom of expression which undermined people’s dignity, or even their safety.

As with other cases using the above paradigm of incitement, in Sanchez the ECtHR does not actually conduct an adequate contextual and legal analysis to ascertain whether, and if so, how, there is an incitement to hatred. In fact, it is doubtful whether the comments were severe enough to justify the use of criminal law and, in addition, whether the applicant, who was not the creator of the comments, should be criminally liable for the content of others. It is doubtful at best whether the users’ comments were actually severe enough to justify the imposition of criminal penalties. In relation to criminal penalties, the position of the United Nation’s Special Rapporteur on the Protection and Promotion of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression is reiterated, namely, that ‘only serious and extreme instances of incitement to hatred […] should be criminalized’.[63] Also, the Rabat Plan of Action underlines that ‘criminal sanctions related to unlawful forms of expression should be seen as last resort measures’.[64] In relation to the ‘proxy’ aspect of the case, it was not the applicant himself who made the impugned comments but rather other Facebook users. The ECtHR noted that, by allowing his Facebook wall to be public, Sanchez assumed responsibility for the content of the comments posted. It agreed with the French court which found that Sanchez left the comments up for six weeks before removing them and was thus guilty as the producer of an online public communication site, and thus the principal offender. Notable is the fact that Sanchez did post a message asking users to monitor the content of their comments. Here, the ECtHR transposed its Delfi v Estonia findings, which involved the content moderation responsibility of a news portal to an individual, placing this duty within the responsibilities the applicant had as a political candidate. To this end, it held that, although (in theory) political parties enjoy a wide freedom of expression in an electoral context, this did not extend to racist or xenophobic discourse and that politicians had a particular responsibility in combatting hate speech. Although the speech was not his own, this did not appear to affect the court’s decision in finding no violation of Article 10, even though a criminal penalty had been imposed on the applicant. Referral to the Grand Chamber has been accepted and the hearing was set for May 2022.

4.2.2.2 Beizaras and Levickas v Lithuania (2020)[65]

This case involved a Facebook post by one of the applicants with a photograph of him kissing his male partner who was the second applicant. This resulted in hundreds of hateful and discriminatory comments under the post. This case differs from the majority of the court’s cases on hate speech as it emanated from the victim of the speech rather than the speaker. The applicants held that the national authorities’ refusal to launch a pre-trial investigation into the comments left under the post amounted to a violation of Article 8 in conjunction with Article 14. The court held that the applicants had been denied an effective remedy and that their right to private life in conjunction with the right to non-discrimination had been violated as a result of the authorities’ stance. Importantly, this case reflects an ex officio duty to restrict Article 10 in cases of content which the Court broadly understands to be hate speech.

5 Conclusion

The Internet is a giant, a social, legal, and moral one. It has emancipated information and expression to levels that were previously unimaginable. Some of this information may amount to hate speech, in that it is directed towards persons or groups because of their particular protected characteristics. Some of this speech may even amount to illegal hate speech, transcending the thresholds of legally acceptable speech as set out, for purposes of the present discussion, in international and European documents. So, what do we do with that type of speech? This paper demonstrates how seeking to tackle all types of hate speech through enhanced pressures on intermediaries to remove content may come with dire effects to both freedom of expression and the right to non-discrimination. At the same time, due attention must be given to speech which may actually lead to real world harm. A perfect solution is not available since, as is the case in the real world, the Internet cannot be expected to be perfect. However, at the very least, the principles and precepts of IHRL and the thresholds attached to Article 20(2) ICCPR, as further interpreted by the Rabat Plan of Action, must inform and guide any effort in enhanced platform liability.

[1] Simon Kemp, Digital 2022: Global Overview Report (DataReportal, 26 January 2022) <https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-global-overview-report> accessed 21 December 2022.

[2] UN Human Rights Council (UNHRC), ‘Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression’ (22 May 2015) UN Doc A/HRC/29/32, para 11.

[3] Times Newspaper Ltd (Nos 1 and 2) v the United Kingdom [2009] EMLR 14, [27].

[4] UN HRC, ‘General Comment 34: Article 19: Freedoms of opinion and expression’ (12 September 2011) UN Doc CCPR/C/GC/34, para 15.

[5] Jacob Mchangama, Natalie Alkiviadou and Raghav Mendiratta, ‘A Framework of First Reference: Decoding a human rights approach to content moderation in the era of “platformization”’ (Justita, November 2021), 4 <https://futurefreespeech.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Report_A-framework-of-first-reference.pdf> accessed 21 December 2022.

[6] UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, ‘Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights’ (2011) <https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/publications/guidingprinciplesbusinesshr_en.pdf> accessed 1 August 2022.

[7] This has been done in, inter alia, Uladzislau Belavusau, Freedom of Speech: Importing European and US Constitutional Models in Transitional Democracies (Routledge 2013), 41; Mark Slagle, ‘An Ethical Exploration of Free Expression and The Problem of Hate Speech’ 24 Journal of Mass Media Ethics 238, 242; Tarlach McGonagle, ‘Wrestling (Racial) Equality From Tolerance of Hate Speech’ (2001) 23 Dublin University Law Journal 21, 23.

[8] UNHRC, ‘Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression’ (7 September 2012) UN Doc A/67/357, para 45.

[9] Declaration to the ICERD by France available here: <https://indicators.ohchr.org/> accessed 25 December 2022.

[10] Declaration to the ICCPR by Luxembourg available here: <https://indicators.ohchr.org/> accessed 25 December 2022.

[11] Additional Protocol to the Cybercrime Convention, Treaties Collections, Finland: ‘The Republic of Finland, due to established principles in its national legal system concerning freedom of expression, reserves the right not to apply, in whole or in part, Article 5, paragraph 1, to cases where the national provisions on defamation or ethnic agitation are not applicable’.

[12] Council of Europe Committee of Ministers, ‘Recommendation No. R (97) 20 of the Committee of Ministers to member states on “hate speech”’ (Adopted by the Committee of Ministers on 30 October 1997 at the 607th Meeting of the Ministers’ Deputies).

[13] Lilliendahl v Iceland App no 29297/18 (ECtHR, 12 May 2020), para 33.

[14] Mchangama, Alkiviadou and Mendiratta (n 5).

[15] Meta Transparency Centre, ’Hate Speech’ <https://transparency.fb.com/policies/communitystandards/hate-speech/> accessed 25 December 2022.

[16] Alexander Brown, ‘What is So Special about Online (as Compared to offline) Hate Speech?’ (2018) 18(3) Ethnicities 297, 308.

[17] Alexandra Siegel, ‘Online Hate Speech’ in Nathaniel Persily and Joshua Tucker, Social Media and Democracy – The State of the Field, Prospects for Reform (CUP 2020).

[18] Milmo Dan, ‘Rohingya sue Facebook for £150bn over Myanmar Genocide’ (The Guardian, 2021) <https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2021/dec/06/rohingya-sue-facebook-myanmar-genocide-us-uk-legal-action-social-media-violence> accessed 21 December 2022.

[19] Mchangama, Alkiviadou and Mendiratta (n 5).

[20] Mchangama, Alkiviadou and Mendiratta (n 5).

[21] Meta, Transparency Center, ‘Facebook Community Standards: Hate Speech’ <https://transparency.fb.com/policies/community-standards/hate-speech/> accessed 1 August 2022.

[22] Google, ‘Transparency Report: YouTube Community Guidelines enforcement’ <https://transparencyreport.google.com/youtube-policy/removals> accessed 21 December 2022.

[23] Natasha Duarte and Emma Llansó, ‘Mixed Messages? The Limits of Automated Social Media Content Analysis’ (CDT, 28 November 2017) <https://cdt.org/insights/mixed-messages-the-limits-of-automated-social-media-content-analysis/> accessed 21 December 2022.

[24] Meta, Transparency Center (n 17).

[25] Thiago Oliva Dias et al, ‘Fighting Hate Speech, Silencing Drag Queens? Artificial Intelligence in Content Moderation and Risks to LGBTQ Voices Online’ (2021) 25 Sexuality & Culture, 714

[26] Maarten Sap et. al, ‘The Risk of Racial Bias in Hate Speech Detection’ in Anna Korhonen et. al (Ed.), Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL 2019), 1672.

[27] Lilian Edwards, The Role and Responsibility of Internet Intermediaries in the Field of Copyright and Related Rights (WIPO 2016), 5.

[28] Ibid.

[29] Ibid.

[30] Olivier Sylvain, ‘Intermediary Design Duties’ (2018) 50(1) Connecticut Law Review 203, 212.

[31] Brown (n 12), 310.

[32] YU Wenguang, ‘Internet Intermediaries’ Liability for Online Illegal Hate Speech’ (2018) 13(3) Frontiers of Law in China 342, 356.

[33] Jacob Mchangama, Natalie Alkiviadou and Raghav Mendiratta, ‘Rushing to Judgement: Are Short Mandatory Takedown Limits for Online Hate Speech Compatible with the Freedom of Expression?’ (Justitia, January 2021), 2 <https://futurefreespeech.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/FFS_Rushing-to-Judgment-3.pdf> accessed 21 December 2022..

[34] Jacob Mchangama and Joelle Fiss, ‘The Digital Berlin Wall: How Germany (Accidentally) Created a Prototype for Global Online Censorship’ (Justitia, November 2019) <https://futurefreespeech.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/analyse-the-digital-berlin-wall-how-germany-accidentally-created-a-prototype-for-global-online-censorship.pdf> accessed 21 December 2022; Jacob Mchangama and Natalie Alkiviadou, ‘‘The Digital Berlin Wall: How Germany (Accidentally) Created a Prototype for Global Online Censorship – Act 2’ (Justitia, September 2020) <https://futurefreespeech.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/Analyse_Cross-fertilizing-Online-Censorship-The-Global-Impact-of-Germanys-Network-Enforcement-Act-Part-two_Final.pdf> accessed 21 December 2022.

[35] CPJ, ‘302 Journalists Imprisoned’ (1 December 2021)<https://cpj.org/data/imprisoned/2021/?status=Imprisoned&charges%5B%5D=False%20News&start_year=2021&end_year=2021&group_by=location> accessed 1 August 2022.

[36] Jacob Mchangama and Raghav Mendiratta, ‘Time to end India’s War on Sedition’ (Lawfare, 25 June 2021) <https://www.lawfareblog.com/time-end-indias-war-sedition> accessed 21 December 2022.

[37] Yohannes Eneyew Ayalew, ‘Is Ethiopia’s First Fake News Case in Line with Human Rights Norms?’ (Ethiopia Insight, 1 May 2020) <https://www.ethiopia-insight.com/2020/05/01/is-ethiopias-first-fake-news-case-in-line-with-human-rights-norms/> accessed 1 August 2022.

[38] Befeqadu Z. Hailu, ‘Did the Ethiopian Government use its Covid-19 Restrictions to Silence Dissent?’ (Global Voices, 23 March 2021) <https://globalvoices.org/2021/03/23/did-the-ethiopian-government-use-its-covid-19-restrictions-to-silence-dissent/> accessed 1 August 2022.

[39] UNHRC, ‘Report of the Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression’ (13 April 2021) UN Doc A/HRC/47/25 para58.

[40] Decision n ° 2020-801 DC (French Constitutional Court, June 18, 2020).

[41] Patrick Breyer, ‘French Law on Illegal Content Online Ruled Unconstitutional: Lessons for the EU to Learn.’ (19 November 2020) <https://www.patrick-breyer.de/en/french-law-on-illegal-content-online-ruled-unconstitutional-lessons-for-the-eu-to-learn/> accessed on 21 December 2022.

[42] Anu Bradford, ‘The Brussels Effect: How the European Union Rules the World’ (OUP 2019).

[43] Jacob Mchangama, Natalie Alkiviadou and Raghav Mendiratta, ‘Thoughts on the DSA: Challenges, Ideas and the Way Forward through International Human Rights Law’ (Justitia, 2022) <https://futurefreespeech.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/Report_thoughts-on-DSA.pdf> accessed 1 August 2022.

[44] Vera Jourova, Commissioner for Values and Transparency, ‘One step further in tackling xenophobia and racism in Europe‘ (Speech at the Launch of the EU High Level Group on Combating Racism, Xenophobia and Other Forms of Intolerance, 14 June 2016) <https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/SPEECH_16_2197> accessed 21 December 2022.

[45] Commission, ‘6th evaluation of the Code of Conduct’ (7 October 2021) .

[46] Adina Portaru, ‘Freedom of Expression Online: The Code of Conduct on Countering Illegal “Hate Speech” Online’ (2017) 2017 (4) RRDE 78, 78.

[47] Ibid 316.

[48] Delfi AS v Estonia App no 64569/09 (ECtHR, 16 June 2015), para 162.

[49] Ibid para 156.

[50] Mchangama, Alkiviadou and Mendiratta (n 33).

[51] Ibid para 162.

[52] Ibid.

[53] Ibid para 157.

[54] Ibid para 162.

[55] Ibid para 157.

[56] Tatiana Synodinou, ‘Intermediaries’ Liability for Online Copyright Infringement in the EU: Evolutions and Confusions’ (2015) 31(1) Computer Law & Security Review 57, 63.

[57] Hugh J. McCarthy, ‘Is the Writing on the Wall for Online Service Providers? Liability for Hosting Defamatory User-Generated Content Under European and Irish Law’ (2015) 14 Hibernian Law Journal 39.

[58] Ibid.

[59] Council of Europe, European Digital Rights (EDRi), ‘Human Rights Violations Online’ DGI (2014) 31, 4 December 2014 <https://edri.org/files/EDRI_CoE.pdf> accessed 21 December 2022.

[60] Sanchez v France App no 45591/15 (ECtHR, 2 September 2021).

[61] Natalie Alkiviadou, ‘Hate Speech by Proxy: Sanchez v France and the Dwindling Protection of Freedom of Expression’ (OpinioJuris, 14 December 2021) <http://opiniojuris.org/2021/12/14/hate-speech-by-proxy-sanchez-v-france-and-the-dwindling-protection-of-freedom-of-expression/> accessed 21 December 2022.

[62] As initially developed in Féret v Belgium App no 15615/07 (ECtHR, 16 July 2009) and then in Vejdeland v Sweden App no 1813/07 (ECtHR, 9 May 2012) and Atamanchuk v Russia App no 4493/11 (ECtHR, 12 October 2020).

[63] UNHRC (n 8), para 47.

[64] UNHRC, ‘Rabat Plan of Action on the prohibition of advocacy of national, racial or religious hatred that constitutes incitement to discrimination, hostility or violence’ (11 January 2013) UN Doc A/HRC/22/17/Add.4, 6.

[65] Beizaras and Levickas v Lithuania App No 41288/15 (ECtHR, 14 January 2020).